- Patent ductus arteriosus

-

Patent ductus arteriosus Classification and external resources

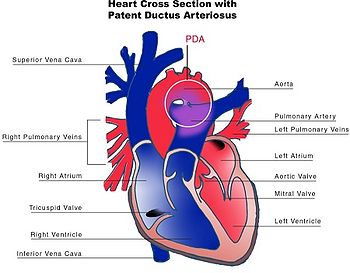

Heart cross-section with PDAICD-10 Q25.0 ICD-9 747.0 OMIM 607411 DiseasesDB 9706 MedlinePlus 001560 eMedicine emerg/358 MeSH C14.240.400.340 Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a congenital disorder in the heart wherein a neonate's ductus arteriosus fails to close after birth. Early symptoms are uncommon, but in the first year of life include increased work of breathing and poor weight gain. With age, the PDA may lead to congestive heart failure if left uncorrected.

Contents

Overview

Etiology

A patent ductus arteriosus can be idiopathic (i.e. without an identifiable cause), or secondary to another condition. Some common contributing factors in humans include:

- Preterm birth

- Congenital rubella syndrome

- Chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome

Normal ductus arteriosus closure

In the developing fetus, the ductus arteriosus (DA) is the vascular connection between the pulmonary artery and the aortic arch that allows most of the blood from the right ventricle to bypass the fetus' fluid-filled compressed lungs. During fetal development, this shunt protects the right ventricle from pumping against the high resistance in the lungs, which can lead to right ventricular failure if the DA closes in-utero.

When the newborn takes its first breath, the lungs open and pulmonary vascular resistance decreases. After birth, the lungs release bradykinin to constrict the smooth muscle wall of the DA and reduce bloodflow through the DA as it narrows and completely closes, usually within the first few weeks of life. In most newborns with a patent ductus arteriosus the blood flow is reversed from that of in utero flow, i.e. the blood flow is from the higher pressure aorta to the now lower pressure pulmonary arteries.

In normal newborns, the DA is substantially closed within 12–24 hours after birth, and is completely sealed after three weeks. The primary stimulus for the closure of the ductus is the increase in neonatal blood oxygen content. Withdrawal from maternal circulating prostaglandins also contributes to ductal closure. The residual scar tissue from the fibrotic remnants of DA, called the ligamentum arteriosum, remains in the normal adult heart.

Patent ductus arteriosus

The ductus arteriosus is a normal fetal blood vessel that closes soon after birth. In a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) the vessel does not close and remains "patent" resulting in irregular transmission of blood between two of the most important arteries close to the heart, the aorta and the pulmonary artery. PDA is common in neonates with persistent respiratory problems such as hypoxia, and has a high occurrence in premature children. In hypoxic newborns, too little oxygen reaches the lungs to produce sufficient levels of bradykinin and subsequent closing of the DA. Premature children are more likely to be hypoxic and thus have PDA because of their underdeveloped heart and lungs.

A patent ductus arteriosus allows a portion of the oxygenated blood from the left heart to flow back to the lungs by flowing from the aorta (which has higher pressure) to the pulmonary artery. If this shunt is substantial, the neonate becomes short of breath: the additional fluid returning to the lungs increases lung pressure to the point that the neonate has greater difficulty inflating the lungs. This uses more calories than normal and often interferes with feeding in infancy. This condition, as a constellation of findings, is called congestive heart failure.

In some cases, such as in transposition of the great vessels (the pulmonary artery and the aorta), a PDA may need to remain open. In this cardiovascular condition, the PDA is the only way that oxygenated blood can mix with deoxygenated blood. In these cases, prostaglandins are used to keep the patent ductus arteriosus open.

Prognosis

Without treatments, the disease may progress from left-to-right (noncyanotic heart) shunt to right-to-left shunt (cyanotic heart) called Eisenmenger's syndrome.

Signs and symptoms

While some cases of PDA are asymptomatic, common symptoms include:

- tachycardia

- respiratory problems

- dyspnea - shortness of breath

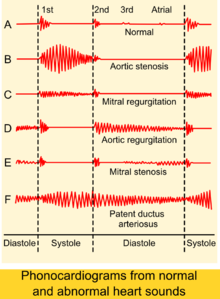

- continuous machine-like heart murmur

- cardiomegaly - enlarged heart

- left subclavicular thrill

- bounding pulse

- widened pulse pressure

- patients typically present in good health, with normal respirations and heart rate. If the ductus is moderate or large, widened pulse pressure and bounding peripheral pulses are frequently present, reflecting increased left ventricular stroke volume and diastolic runoff of blood into the initially lower-resistant pulmonary vascular bed. Prominent suprasternal and carotid pulsations may be noted secondary to increased left ventricular stroke volume.

- poor growth[1]

- differential cyanosis, i.e. cyanosis of the lower extremities but not of the upper body.

Diagnosis

PDA is usually diagnosed using non-invasive techniques. Echocardiography, in which sound waves are used to capture the motion of the heart, and associated Doppler studies are the primary methods of detecting PDA. Electrocardiography (ECG), in which electrodes are used to record the electrical activity of the heart, is not particularly helpful as there are no specific rhythms or ECG patterns which can be used to detect PDA.

A chest X-ray may be taken, which reveals the overall size of neonate's heart (as a reflection of the combined mass of the cardiac chambers) and the appearance of the blood flow to the lungs. A small PDA most often shows a normal sized heart and normal blood flow to the lungs. A large PDA generally shows an enlarged cardiac silhouette and increased blood flow to the lungs.

Treatment

Neonates without adverse symptoms may simply be monitored as outpatients, while symptomatic PDA can be treated with both surgical and non-surgical methods.[2] Surgically, the DA may be closed by ligation (though support in premature infants is mixed),[3] wherein the DA is manually tied shut, or with intravascular coils or plugs that leads to formation of a thrombus in the DA. This was first performed in humans by Robert E. Gross[citation needed].

Because Prostaglandin E1 is responsible for keeping the ductus patent, NSAIDS (inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis) such as indomethacin or a special form of ibuprofen have been used to help close a PDA.[1][4] This is an especially viable alternative for premature infants.[citation needed]

In certain cases it may be beneficial to the neonate to prevent closure of the ductus arteriosus[citation needed]. For example, in transposition of the great vessels, a PDA may prolong the newborn's life until surgical correction is possible. The ductus arteriosus can be induced to remain open by administering prostaglandin analogs such as alprostadil or misoprostol (prostaglandin E1 analogs)[citation needed].

More recently, PDAs can be closed by percutaneous interventional method[citation needed]. Via the femoral vein or femoral artery, a platinum coil can be deployed via a catheter, which induces thrombosis (coil embolization). Alternatively, a PDA occluder device (AGA Medical)[citation needed], composed of nitinol mesh, is deployed from the pulmonary artery through the PDA. The larger skirt of the device sits on the aortic side while the ampulla of the device hugs the walls of the PDA, with care taken to avoid occlusion of the pulmonary arterial lumen by the device[citation needed]. These methods permit closure without open heart surgery.

History

Robert E. Gross, MD performed the first successful ligation of a patent ductus arteriosus on an eight year old girl at Children's Hospital Boston in 1938.

Additional images

References

- ^ a b MedlinePlus > Patent ductus arteriosus Update Date: 21 December 2009

- ^ Zahaka, KG and Patel, CR. "Congenital defects'". Fanaroff, AA and Martin, RJ (eds.). Neonatal-perinatal medicine: Diseases of the fetus and infant. 7th ed. (2002):1120-1139. St. Louis: Mosby.

- ^ Mosalli R, Alfaleh K, Paes B (July 2009). "Role of prophylactic surgical ligation of patent ductus arteriosus in extremely low birth weight infants: Systematic review and implications for clinical practice". Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2 (2): 120–6. doi:10.4103/0974-2069.58313. PMC 2922659. PMID 20808624. http://www.annalspc.com/article.asp?issn=0974-2069;year=2009;volume=2;issue=2;spage=120;epage=126;aulast=Mosalli.

- ^ MayoClinic > Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) Dec. 22, 2009

External links

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus information from Seattle Children's Hospital Heart Center

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus Causes from US Department of Health and Human Services

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus from Merck

- Fetal Circulation at berkeley.edu

- Information about PDA - The Hospital for Sick Children

- Down's Heart Group Easy to understand diagram and explanation of PDA.

- PDA Occluder Amplatzer PDA occluder device used for percutaneous closure of PDAs.

- Children's Hospital Boston Archives

Congenital vascular defects / Vascular malformation (Q25–Q28, 747) Great arteries/

other arteriesPatent ductus arteriosus · Coarctation of the aorta · Interrupted aortic arch · Overriding aorta · Aneurysm of sinus of Valsalva · Vascular ringPulmonary atresia · Stenosis of pulmonary arterySingle umbilical arteryGreat veins Arteriovenous malformation Categories:- Congenital heart disease

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.