- Leonard Jeffries

-

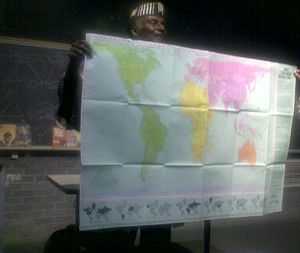

Dr. Leonard Jeffries

Holding up a Gall–Peters projection map, a map showing the areas of the continents in proper proportion.Born January 19, 1937

Newark, New Jersey[1]Occupation Professor of Black Studies Spouse Rosalind Robinson Jeffries, art historian Parents Leonard Jeffries (father) Leonard Jeffries Jr. (born 1937) is an American professor of black studies at the City College of New York, part of the City University of New York. He achieved national prominence in the early 1990s for his controversial statements about Jews and other white people. In a 1991 speech he claimed that Jews financed the slave trade, used the movie industry to hurt black people, and that whites are "ice people" while Africans are "sun people". Jeffries was discharged from his position as chairman of the black studies department at CUNY, leading to a lengthy legal battle.[2][3][4]

Contents

Academic career

Jeffries attended Lafayette College for his undergraduate work. While in Lafayette, Jeffries pledged, and was accepted into, Pi Lambda Phi, "the Jewish fraternity,"[1] which was the only fraternity at Lafayette that would accept black students. In his senior year, Jeffries was elected president of the fraternity, and as a result, his room and board expenses were paid for by the fraternity. After graduating with honors in 1959, Jeffries won a Rotary International fellowship to the University of Lausanne in Switzerland and then returned in 1961 to study at Columbia University's School of International Affairs from which he received a master's degree in 1965. At the same time he worked for Operation Crossroads Africa allowing him to spend time in Guinea, Mali, Senegal, and the Ivory Coast, and became the program coordinator for West Africa in 1965. Jeffries became a political science instructor at CCNY in 1969 and received his doctorate in 1971 with a dissertation on politics in the Ivory Coast. He became the founding chairman of Black Studies at San Jose State College in California. A year later, he became a tenured professor at CCNY and became the chairman of the new African-American Studies Department. It was unusual for an inexperienced scholar to both receive tenure and a chair.[1][2]

He held the position of chairman of CCNY's Black Studies Department for over two decades, recruiting like-minded scholars and growing the department. Besides administration and teaching, he often travelled to Africa and served in the African Heritage Studies Association, a group seeking to define and develop the black studies discipline. Jeffries did not publish much original scholarship. He told the New York magazine "My students say, 'Doctor J., why don't you write?' I say, 'I can't--I'm making history so I don't have time to write it.'"[1][2][5]

Jeffries became popular among his students and as a speaker at college campuses and in public. He is known for radical Afrocentrist views—that the role of African people in history and the accomplishments of African Americans is far more important than commonly held.[1]

Controversy

Jeffries became known outside his field in 1987 when he was on a state task force to fight racism in the public school curriculum. Its publication A Curriculum of Inclusion harshly criticized the public school syllabi for Eurocentrism and demanded revisions to emphasize African history and accomplishments of African Americans. He often clashed with Diane Ravitch, a Jewish member of the task force.[1][6]

Jeffries had also advanced a theory that whites are "ice people" who are violent and cruel, while blacks are "sun people" who are compassionate and peaceful.[7] He is a proponent of melanin theory and claims that melanin levels affect the psyche of people, and that melanin allows black people to "…negotiate the vibrations of the universe and to deal with the ultraviolet rays of the sun."[8]

His lectures and talks have been characterized as "racist rants".[9][10][11][12]

In an interview in Rutherford Magazine May 1995 Jeffries, asked what kind of world he would want to leave to his children, he answered: "A world in which there aren’t any white people".[13]

Jeffries has said that the 1986 Challenger Space Shuttle disaster was "the best thing to happen to America in a long time," as it would stop white people from "spreading their filth through the universe."[7]

Philip Gourevitch at Commentary calls him "a black supremacist who uses his classroom to teach his notion that the skin pigment melanin endows blacks with physical and intellectual superiority."[1]

During the court cases, Jeffries made a speech where he represented white people with various animals, English as elephants, Dutch as squirrels, and Jews as skunks who "stunk up everything". [3]

1991 speech

See also: Jews and the slave tradeOn July 20, 1991, Jeffries held a controversial speech at the Empire State Black Arts and Cultural Festival, in Albany, New York. During the two hour speech,[14] he said that "rich Jews" financed the slave trade and control the film industry together with Italian mafia, using it to paint a brutal stereotype of blacks. He also attacked Diane Ravitch, calling her a "sophisticated Texas Jew," "a debonair racist" and "Miss Daisy."[1][2][9][15]

Later, after the local cable television channel NY-SCAN broadcast the speech and the New York Post reported on it, many journalists and some Jewish leaders criticized Jeffries for bigoted, racist and antisemitic remarks.[1][2][15] Washington Post critic Jonathan Yardley wrote, "Talk such as Jeffries engaged in at Albany has nothing to do with 'ideas' -- it's bigotry, pure and simple."[9] Another New York columnist called it "pure Goebbels".[2] New York Governor Mario Cuomo said Jeffries rant was "so egregious that the City University ought to take action or explain why it doesn't," but later defended Jeffries' "freedom to abuse [freedom]."[9] New York Senator Alfonse D'Amato also demanded Jeffries' resignation. The chancellor of CUNY, W. Ann Reynolds said in a statement that she was shocked and deeply disturbed by the speech.[2]

When Jeffries returned from a trip to Africa he was met by nearly 1,000 of his supporters at the airport, as well as a handful of mostly Jewish protesters from a group called Kahane Chai.[9][16] Students picketed his public appearances and outside his home. Jeffries told Emerge that he received hate mail, phone calls to his home, and death threats. He had bodyguards follow him on campus. Others felt threatened by Jeffries and his bodyguards. A Jewish student from Harvard University said that Jeffries threatened him during an interview for The Harvard Crimson.[1][3]

Removal as chairman and legal battles

In 1992 Jeffries first got his term shortened from three years to one, and was then removed as chairman from the department of African-American studies, but was allowed to stay as a professor. Jeffries sued the school and in August 1993 a federal jury found that his First Amendment rights had been violated. The school held that the demotion was not because of his speech, but for inefficiency, tardiness, sending grades to the school by mail, and brutish behavior. However, only a month before the speech Jeffries had been unanimously reappointed as chairman. He was restored as chairman and awarded $400,000 in damages (later reduced to $360,000).[17][18][19]

The school appealed, but the federal appeals court upheld the verdict while removing the damages. The CUNY Institute for Research on the Diaspora in the Americas and Caribbean was created to do black research independent of Jeffries' department. It was headed by Edmund W. Gordon, who had led the Black Studies Department before Jeffries was reinstated. In November 1994 the Supreme Court told the appeals court to reconsider after a related Supreme Court decision.[20] The appeals court reversed its decision in April 1995,[21] and in June the same year Prof. Moyibi Amodo was elected to succeed Jeffries as department chairman. Jeffries remains a professor at CCNY.[1][3][4][22]

Later debate

The Jeffries case led to debate about tenure, academic freedom and free speech.[17][22][23] He was sometimes compared to Michael Levin, a Jewish CUNY professor who outside of the classroom claimed that black people are inferior, and had recently won against the school in court.[3][9]

One interpretation of the Jeffries case is that while a university cannot fire a professor for opinions and speech, they have more flexibility with a position like department chair. Another is that it allows public institutions to discipline employees in general for disruptive speech.[2]

See also

- African-American – Jewish relations #Black anti-semitism

- Afrocentrism

- Anti-Europeanism

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Contemporary Black Biography. The Gale Group. 2006. http://www.answers.com/topic/leonard-jeffries. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Foerstel, Herbert N. (1997). "Jefferies, Leonard". Free expression and censorship in America: an encyclopedia. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 101–102,132. ISBN 9780313292316. OCLC 35317918. LCCN 96-42157. http://books.google.com/books?id=_eFgZJCX8VUC&pg=PA127. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Abel, Richard L. (1999). Speaking Respect, Respecting Speech. University of Chicago Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0226000575. http://books.google.com/?id=kf0zqDyLgBkC&pg=PA101. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ^ a b David Singer, Ruth R. Seldin, ed (1996). American Jewish Year Book 1996. New York: The American Jewish Committee. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0874951100. http://books.google.com/?id=daFeyrLbqy0C&pg=PA120. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ^ New York, September 2, 1991, pp. 33-37; May 24, 1993, pp. 10-11.

- ^ Binder, Amy J. (2002). "History of Three Afrocentric Cases: Atlanta, Washington D.C., and New York State" (Google Book Search). Contentious Curricula: Afrocentrism and Creationism in American Public Schools. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 87–101. ISBN 9780691091808. OCLC 48450945. LCCN 2001-058001. http://books.google.com/books?id=p-B9v7AkjZcC&pg=PA87. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ a b "A Deafening Silence". National Review. September 9, 1991. Archived from the original on 2004. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1282/is_n16_v43/ai_11239116. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ Calabresi, Massimo (February 14, 1994). "Dispatches Skin Deep 101". TIME 143 (7). http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,980105,00.html. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Morrow, Lance (June 24, 2001). "Controversies: The Provocative Professor". TIME. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,157721,00.html. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- ^ Peyser, Andrea (June 15, 2006). "Spewing Racism on the City Dime — More Anti-White Rants from CUNY Prof". New York Post. p. 5. Archived from the original on Unknown. http://www.discoverthenetworks.org/Articles/Spewing%20Racism%20on%20the%20City%20Dime.html. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ Chavez, Linda (March 19, 2008). "Afrocentrism Is the Problem: Beyond Obama’s Wright". National Review. http://article.nationalreview.com/?q=NjZkMmI1ODIwZTgxMWQzZDg3YTM4ODk0ZTEzMjhhOWQ=. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ George, Robert P.. "Academic Freedom: The Grounds for Tolerating Abuses". The Mind and Heart of the Church 4 (1991). The Wethersfield Institute / Ignatius Press. pp. 43–50. http://www.catholiceducation.org/articles/education/ed0074.html. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ^ "Rutherford Magazine" p. 13, May 1995. Leonard Jeffries interviewed by T.L. Stanclu and Nisha Mohammed

- ^ ""Our Sacred Mission", speech at the Empire State Black Arts and Cultural Festival in Albany, New York, July 20, 1991". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. http://web.archive.org/web/20070927100739/http://www.nbufront.org/html/MastersMuseums/LenJeffries/OurSacredMission.html.

- ^ a b "Due Process for Leonard Jeffries? (editorial)". New York Times: pp. section A page 20. May 14, 1993. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/05/14/opinion/due-process-for-leonard-jeffries.html. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- ^ Barron, James (August 15, 1991). "Professor Steps Off a Plane Into a Furor Over His Words". New York Times: pp. B3. http://www.nytimes.com/1991/08/15/nyregion/professor-steps-off-a-plane-into-a-furor-over-his-words.html. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ a b "Academic Freedom". West's Encyclopedia of American Law. The Gale Group. 1998. http://www.answers.com/topic/academic-freedom. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ Newman, Maria (May 12, 1993). "CUNY Violated Speech Rights Of Department Chief, Jury Says". New York Times: pp. A1. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/05/12/nyregion/cuny-violated-speech-rights-of-department-chief-jury-says.html. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard (August 5, 1993). "Judge Reinstates Jeffries as Head Of Black Studies for City College". New York Times: pp. A1. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/05/nyregion/judge-reinstates-jeffries-as-head-of-black-studies-for-city-college.html. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ Waters v. Churchill (114 S.Ct. 1878 [1994]), 511 U.S. 661 (1994)

- ^ Jeffries v. Harleston, 52 F.3d 9 [2nd Cir. 1995]

- ^ a b Finkin, Matthew W. (1996). The case for tenure. Cornell University Press. pp. 190–191. ISBN 0801433169. http://books.google.com/?id=lvAf7TOoDi0C&pg=PA190. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ Spitzer, Robert J. (1994). "Tenure, Speech, and the Jeffries Case: A Functional Analysis". Pace Law Review 15 (111). http://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=info:R8GwDGmu3sEJ:scholar.google.com/&output=viewport. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

External links

- Jeffries' on AfricaWithin

- Leonard Jeffries Virtual Museum at the National Black United Front website (Archived from the original)

Categories:- African American academics

- City College of New York faculty

- Lafayette College alumni

- Columbia University alumni

- San Jose State University faculty

- Black supremacy

- 1937 births

- Living people

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.