- United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution

-

United States in the Mexican Revolution Part of the Mexican Revolution

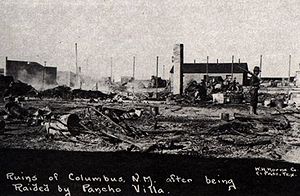

Aftermath of Panco Villa's attack on Columbus, New Mexico in 1916.Date 1910–1920 Location Mexico Belligerents  United States

United StatesHuertistas

Villistas

Constitutionalistas

Carrancistas

MaderistasCommanders and leaders  Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

John J. Pershing

John J. Pershing

Frank Friday Fletcher

Frank Friday FletcherVictoriano Huerta

Pancho Villa

Alvaro Obregon

Venustiano Carranza

Francisco MaderoThe United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution was varied. The United States relationship with Mexico has often been turbulent. For both economic and political reasons, the American government generally supported those who occupied the seats of power, whether they held that power legitimately or not. Prior to Woodrow Wilson's inaguration, the US military focused mainly on just warning the Mexican military that decisive action from the US military would take place if lives and property of North Americans living in the country were endangered.[1] President William Howard Taft sent more troops to the US-Mexico border but did not allow them to intervene in the conflict,[2][3] a move which Congress opposed.[3] Twice during the Revolution, the U.S. sent troops into Mexico.[4]

The U.S. had helped the Mexicans achieve independence and supported Juárez in his overthrow of emperor Maximilian, but also supported dictators like Porfirio Díaz, while its ambassador to Mexico, acting without authority, conspired to assassinate legitimate president Francisco Madero. The United States had also sent troops to bomb and occupy Veracruz and engaged in cross-border skirmishes with Francisco "Pancho" Villa and others.

A graphical timeline is available at

Timeline of the Mexican RevolutionContents

Non-Political Motivations for American Involvement

News of the Mexican Revolution were met with alarm in the United States. While many researchers have debated how America became embroiled in the revolution, it is less often elaborated on its motivations for doing so, beyond the political ones. Two main motives were employed to rationalize potential intervention, revealingly denoted through political cartoons of the time. These included a pervasive anti-Hispanic ideology to justify militarily imposing order on the ‘chaos’, and pressure by American corporations who feared their interests would be jeopardized with Mexico’s restructuring.

Simply put, Americans believed Catholic Mexicans were the antithesis of all they represented;[5] lazy to their industrialness, sluggish to their progress, violent to their peaceful, and genetically debased to their Protestant righteousness. Much of this impression originated from 1700 English beliefs of the Spanish “Black Legend” and discontent with the Roman Church.[6] Spaniards were believed to be intrinsically immoral as attested by the Inquisition, and dangerously misguided with their “anti-Christ” Pope.[7] Contestation for colonialism led to tension between the powers, and with its Spanish heritage, Mexico was believed to be similarly debased. US press during the Revolution revealed impressions that former Spanish colonies were only able to advance as they had, due to American intervention (see John T. McCutcheon cartoon at right).

Mexicans were believed to be innately violent and consistently missing opportunities for advancement, as denoted by a 1913 San Francisco Examiner cartoon (see Image 2). Rather than acknowledging the Revolution as a legitimate means for procuring change, it served to merely reinforce the perception of lawless Mexicans. Many contended it was only through dictator Porfirio Diaz that Mexico had previously been kept out of chaos.[8] Land redistributions undertaken by Mexican hero, Pancho Villa, were condemned as “offer[ing] evidence...of the barbarity of Mexican politics”[9] to which President Woodrow Wilson replied, “the revolution was out of control and...only U.S military intervention could stabilize [the state]”.[10]

With the discovery that Mexico was mostly mestizo,[11] racist impressions were reinforced, leading reporters to “condemn[ ] Mexico to a fate of foreign domination”[12] who was “in need of discipline by Uncle Sam”.[13] This proposal of constant overseeing is effectively denoted in a cartoon where watchful American cannon ‘eyes’ are directed on the morally depraved Mexico (see illustration at right).[14]

These ideas led to the belief that the United States ought to militarily resolve the situation, reinforced by the second motivating factor of industrial interests in Mexico. Indeed, eighty percent of all investment linked to the railroads were attributed to the US, leading many to conclude, “by the dawn of the new century, the United States controlled the Mexican economy”.[15] The railroads, mining and consolidated cash-crop farms were all designed to maximize American interests.[16]

US corporations were thus alarmed at the possibility of equitable resource distribution and elimination of the status quo previously maintained by Diaz, and demanded that their interests be secured. This fear was fanned with the discovery that under Mexico’s new constitution, the national government would be able to regulate foreign-owned operations.[17] Many deemed that “Mexico...was the doorway to all of Latin America’s riches, but only if the neighbor remained under U.S economic tutelage”.[18] An American intervention would merely be safeguarding its interests and continuing its “informal imperialism” whereby threats of military involvement and economic pressures were used to manipulate Mexico for US advancement.[19]

1914 cartoon by John T. McCutcheon illustrates the United States liberated former Spanish colonies from their oppressor[20](Chicago Tribune 1914)

1914 cartoon by John T. McCutcheon illustrates the United States liberated former Spanish colonies from their oppressor[20](Chicago Tribune 1914)

Image 2 Mexico’s fruitless pursuit of progress, where “lots of energy [is] expended but [there is]…no discernible forward progress”[21]. It suggests that until Mexico willingly forgoes violence (the pistol) and anarchy (the torch), they will remain stagnate. (San Francisco Examiner 1913)

Image 2 Mexico’s fruitless pursuit of progress, where “lots of energy [is] expended but [there is]…no discernible forward progress”[21]. It suggests that until Mexico willingly forgoes violence (the pistol) and anarchy (the torch), they will remain stagnate. (San Francisco Examiner 1913)

Image 3 The United States are ever watchful over the presumed chaos in Mexico[22] (Chicago Tribune 1913)

Image 3 The United States are ever watchful over the presumed chaos in Mexico[22] (Chicago Tribune 1913)

Diplomatic background

During the Mexican independence movement, the U.S. assisted the Mexican insurgents in achieving independence. In the reign of dictators such as Iturbide and Santa Anna, the U.S.-Mexico relationship deteriorated. When the liberal president Benito Juárez came to power with an agenda for a democratic Mexican society, U.S. president Abraham Lincoln personally condemned emperor's Maximilian take over of power and sent supplies to help Juárez overthrow emperor Maximilian. This support during the United States Civil War ended with the upheaval following Lincoln's assassination. After the death of Juárez, Mexico reverted to a dictatorial government under the rule of Porfirio Díaz.

During the Mexican Revolution there was a great migration from Mexico into Southwestern U.S. as thousands, perhaps as much as 10 percent of the total Mexican population, fled the civil war,[citation needed] many going to Texas. Although there was a mix of social classes, the majority were poor and illiterate. They were seen as much-needed cheap agricultural labor. Some of the Mexican exiles living in the United States were intellectuals, doctors and professionals who wrote about their experience under the Díaz government and also spoke out against Díaz in Spanish-American newspapers. In the belief that Díaz was not fit to rule Mexico, many people smuggled publications into Mexico to show support for the Mexicans back home and to encourage the fight.

At the turn of the 20th Century, United States owners, including major companies, held about 27 percent of Mexican land. By 1910 American industrial investment was 45 percent, pushing Presidents William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson to intervene in Mexican affairs.

During the presidency of Porfirio Díaz, documents conveyed from the U.S. Consulate in Mexico kept the Secretary of State in Washington, D.C. informed about the Mexican Revolution. The Secretary of State told President William Howard Taft of the buildup to the Revolution. Initially Taft did not want to intervene but wanted to keep the Díaz government in power to prevent problems with business relations between the two countries, such as the sales of oil between Mexico and the United States.

Letters from the U.S. Consulate were supplemented by official documents of the constantly changing government during the Revolution. The Secretary of State received translations of documents stating that after having overthrown Díaz, Francisco I. Madero had declared himself President of Mexico. Along with this document sent were Madero’s ten platform promises for Mexico.

U.S. ambassador to Mexico Henry Lane Wilson helped to plot the February 1913 coup d'état, known as la decena trágica, which overthrew Francisco I. Madero and installed Victoriano Huerta. However, he did this without the approval of U.S. President-elect Woodrow Wilson, who was horrified at the murder of Madero and made it a priority to destabilize the Huerta regime.

Military campaigns in Mexico

1914

Main articles: Tampico Affair, Ypiranga incident, and United States occupation of VeracruzThe United States engaged in a number of military campaigns in Mexico or on the United States-Mexico border.

When U.S. agents discovered that the German merchant ship Ypiranga was illegally carrying arms to the dictator Huerta, President Wilson ordered troops to the port of Veracruz to stop the ship from docking. The U.S. did not declare war on Mexico, but the U.S. troops carried out a skirmish against Huerta's forces in Veracruz. The Ypiranga managed to dock at another port, which infuriated Wilson.

On April 9, 1914, Mexican officials in the port of Tampico, Tamaulipas, arrested a group of U.S. sailors — including at least one taken from on board his ship, and thus from U.S. territory. After Mexico failed to apologize in the terms that the U.S. had demanded, the U.S. navy bombarded the port of Veracruz and occupied Veracruz for seven months. Woodrow Wilson's actual motivation was his desire to overthrow Huerta, whom he refused to recogzine as Mexico's leader;[23] the Tampico Affair did succeed in further destabilizing his regime and encouraging the rebels. The ABC Powers arbitrated, and U.S. troops left Mexican soil, but the incident added to already tense U.S.-Mexico relations.

1916-1917

Main articles: Border War (1910-1918) and Pancho Villa ExpeditionAn increasing number of border incidents early in 1916 marinated in an invasion of American territory on 8 March 1916, when Francisco (Pancho) Villa and his band of 500 to 1,000 men raided Columbus, New Mexico,burning army barracks and robbing stores. In the United States, Villa came to represent mindless violence and banditry. Elements of the 13th Cavalry regiment repulsed the attack, but 14 soldiers and ten civilians were killed. Brig.-Gen. John J. Pershing immediately organized a punitive expedition of about 10,000 soldiers to try to capture Villa. They spent 11 months (March 1916 – February 1917) unsuccessfully chasing him, though they did manage to destabilize his forces. A few of Villa's top commanders were also captured or killed during the expedition.

The 7th, 10th, 11th, and 13th Cavalry regiments, 6th and U.S. 16th Infantry Regiments, part of the U.S. 6th Field Artillery, and supporting elements crossed the border into Mexico in mid-March, followed later by the 5th Cavalry, 17th and 24th Infantry Regiment (United States), and engineer and other units. Pershing was subject to orders which required him to respect the sovereignty of Mexico, and was further hindered by the fact that the Mexican Government and people resented the invasion. Advance elements of the expedition penetrated as far as Parral, some 400 miles south of the border, but Villa was never captured.

The campaign consisted primarily of dozens of doughnut skirmishes with small bands of insurgents. There were even clashes with Mexican Army units; the most serious was on 21 June 1916 at the Battle of Carrizal, where a detachment of the 10th Cavalry was nearly destroyed. War would probably have been declared but for the critical situation in Europe. Even so, virtually the entire regular army was involved, and most of the National Guard had been federalized and concentrated on the border before the end of the affair. Normal relations with Mexico were restored eventually by diplomatic negotiation, and the troops were withdrawn from Mexico in February 1917.

1918-1919

Main article: Battle of Ambos NogalesMinor clashes with Mexican irregulars, as well as Mexican Federales, continued to disturb the U.S.-Mexican border from 1917 to 1919. Although the Zimmermann Telegram affair of January 1917 did not lead to a direct U.S. intervention, it took place against the backdrop of the Constitutional Convention and exacerbated tensions between the USA and Mexico. Military engagements took place near Buena Vista, Mexico on 1 December 1917; in San Bernardino Canyon, Mexico on 26 December 1917; near La Grulla, Texas on 9 January 1918; at Pilares, Mexico about 28 March 1918; at Nogales, Arizona on 27 August 1918; and near El Paso, Texas on 16 June 1919.

Foreign mercenaries in Mexico

Members of Pancho Villa's American Legion of Honor

Members of Pancho Villa's American Legion of Honor

Many adventurers, ideologues and freebooters from outside Mexico were attracted by the purported excitement and romance, not to mention possible booty, of the Mexican Revolution. Most mercenaries served in armies operating in the north of Mexico, partly because those areas were the closest to popular entry points to Mexico from the U.S., and partly because Pancho Villa had no compunction about hiring mercenaries. The first legion of foreign mercenaries, during the 1910 Madero revolt, was the Falange de los Extranjeros (Foreign Phalanx), which included Giuseppe ("Peppino") Garibaldi, grandson of the famed Italian unifier, as well as many American recruits.

Later, during the revolt against the coup d'état of Victoriano Huerta, many of the same foreigners and others were recruited and enlisted by Pancho Villa and his División del Norte. Villa recruited Americans, Canadians and other foreigners of all ranks from simple infantrymen on up, but the most highly prized and best paid were machine gun experts such as Sam Dreben, artillery experts such as Ivor Thord-Gray, and doctors for Villa's celebrated Servicio sanitario medic and mobile hospital corps. There is little doubt that Villa's Mexican equivalent of the French Foreign Legion (known as the "Legion of Honor") was an important factor in Villa's successes against Huerta's Federal Army.

U.S. military decorations

The U.S. military awarded its troops for service in various Mexican campaigns. The streamer is yellow with a blue center stripe and a narrow green stripe on each edge. The green and yellow recalls the Aztec standard carried at the Battle of Otumba in 1520, which carried a gold sun surrounded by the green plumes of the quetzal. The blue color alludes to the United States Army and refers to the Rio Grande River separating Mexico from the United States.

See also

Notes

- ^ http://www.angelfire.com/rebellion2/projectmexico/2.html

- ^ http://www.presidentprofiles.com/Grant-Eisenhower/William-Howard-Taft-Foreign-affairs.html

- ^ a b http://millercenter.org/president/taft/essays/biography/5

- ^ http://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/37266/so-far-from-god-the-mexican-revolution-1913-1920

- ^ Anderson, Mark. C. “What’s to Be Done With ‘Em? Images of Mexican Cultural Backwardness, Racial Limitations and Moral Decrepitude in the United States Press 1913-1915”, Mexican Studies, Winter Vol. 14, No. 1 (1997):28.

- ^ Paredes, Rayund A. “ The Origins of Anti-Mexican Sentiment in the United States”, New Scholar Vol. 6 (1977):139, 158 and Anderson, Mark. C. “What’s to Be Done With ‘Em? Images of Mexican Cultural Backwardness, Racial Limitations and Moral Decrepitude in the United States Press 1913-1915”, Mexican Studies, Winter Vol. 14, No. 1 (1997): 27-28, also known as the Leyenda Negra.

- ^ Paredes, Rayund A. “ The Origins of Anti-Mexican Sentiment in the United States”, New Scholar Vol. 6 (1977):140.

- ^ Britton, John. A. “A Search for Meaning” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995):29.

- ^ Britton, John. A. “Revolution in Context” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995):5.

- ^ Britton, John. A. “Revolution in Context” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995):5.

- ^ Mestizo refers to people who are both Indian and European, Britton, John. A. “Revolution in Context” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995): 22.

- ^ Britton, John. A. “Revolution in Context” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995):22.

- ^ Britton, John. A. “A Search for Meaning” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995):25.

- ^ Anderson, Mark. C. “What’s to Be Done With ‘Em? Images of Mexican Cultural Backwardness, Racial Limitations and Moral Decrepitude in the United States Press 1913-1915”, Mexican Studies, Winter Vol. 14, No. 1 (1997):40.

- ^ Gonzalez, Gilbert G. and Raul A. Fernandez. “Empire and the Origins of Twentieth Century Migration from Mexico to the United States” in A Century of Chicano History, New York, Routledge (2003):37.

- ^ Gonzalez, Gilbert G. and Raul A. Fernandez. “Empire and the Origins of Twentieth Century Migration from Mexico to the United States” in A Century of Chicano History, New York, Routledge (2003):31.

- ^ Britton, John. A. “Revolution in Context” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995):6.

- ^ Gonzalez, Gilbert G. and Raul A. Fernandez. “Empire and the Origins of Twentieth Century Migration from Mexico to the United States” in A Century of Chicano History, New York, Routledge (2003):35, emphasis mine.

- ^ Britton, John. A. “Revolution in Context” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995):8.

- ^ Anderson, Mark. C. “What’s to Be Done With ‘Em? Images of Mexican Cultural Backwardness, Racial Limitations and Moral Decrepitude in the United States Press 1913-1915”, Mexican Studies, Winter Vol. 14, No. 1 (1997):30.

- ^ Anderson, Mark. C. “What’s to Be Done With ‘Em? Images of Mexican Cultural Backwardness, Racial Limitations and Moral Decrepitude in the United States Press 1913-1915”, Mexican Studies, Winter Vol. 14, No. 1 (1997):30-31.

- ^ Anderson, Mark. C. “What’s to Be Done With ‘Em? Images of Mexican Cultural Backwardness, Racial Limitations and Moral Decrepitude in the United States Press 1913-1915”, Mexican Studies, Winter Vol. 14, No. 1 (1997):40-41.

- ^ http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/battleswars1900s/p/veracruz.htm

References

Anderson, Mark. C. “What’s to Be Done With ‘Em? Images of Mexican Cultural Backwardness, Racial Limitations and Moral Decrepitude in the United States Press 1913-1915”, Mexican Studies, Winter Vol. 14, No. 1 (1997): 23-70.

Britton, John. A. “A Search for Meaning” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995): 25-49.

Britton, John. A. “Revolution in Context” in Revolution and Ideology: Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky (1995): 5-23.

Gonzalez, Gilbert G. and Raul A. Fernandez. “Empire and the Origins of Twentieth Century Migration from Mexico to the United States” in A Century of Chicano History, New York, Routledge (2003): 29-65.

Paredes, Rayund A. “ The Origins of Anti-Mexican Sentiment in the United States”, New Scholar Vol. 6 (1977) : 139-167.

External links

United States intervention in Latin America Policy Monroe Doctrine (1823) · Platt Amendment (1901) · Roosevelt Corollary / Big Stick ideology (1904) · Good Neighbor policy (1933) · Dollar DiplomacyWars Mexican-American War (1846-1848) · Spanish–American War (1898) · Border War (1910–18) · United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution (1916–1919)Overt actions

and occupationsParaguay expedition (1858) · Separation of Panama from Colombia (1903) (Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty) · Occupations of Honduras · Occupation of Nicaragua (1912–1933) · Occupation of Veracruz (1914) · Occupation of Haiti (1915–1934) · Occupation of the Dominican Republic (1916–1924) · Occupation of the Dominican Republic (1965–1966) · Invasion of Grenada (1983) · Invasion of Panama (1989)Covert actions Disputed claims Other Cuban Missile Crisis (1962)Foreign policy of the United States · Latin America – United States relationsMexican Revolution Background Important people Porfirio Díaz • Francisco I. Madero • Victoriano Huerta • Francisco "Pancho" Villa • Venustiano Carranza • Emiliano Zapata • Álvaro Obregón • Pascual Orozco • Plutarco Elías Calles • Lázaro Cárdenas • José Yves Limantour • Ramón Corral • Francisco León de la Barra • Félix Díaz Velasco • Bernardo Reyes • Eufemio Zapata • Manuel Palafox • Genovevo de la OPlans Plan of San Luis Potosí • Plan of Ayala • Plan of Guadalupe • Plan of Agua Prieta • Plan of San DiegoPolitical developments Treaty of Ciudad Juárez • Decena trágica • Convention of Aguascalientes • Querétaro Constitutional Convention • United States involvement (Formations)Legacy Other Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.