- Dinosaur size

-

For other large prehistoric reptiles, see Largest prehistoric organisms#Reptiles (Reptilia).

Size has been one of the most interesting aspects of dinosaur science to the general public. This article lists the largest and smallest dinosaurs from various groups, sorted in order of weight and length.

This list excludes unpublished size estimates (such as those for Bruhathkayosaurus, possibly the largest dinosaur of all). In some cases, dinosaurs are known that will be included on this list if/when they are officially described. In addition, weight estimates for dinosaurs are much more variable than length estimates, because estimating length for extinct animals is much more easily done from a skeleton than estimating weight.

Contents

General records

Heaviest dinosaurs

See also Most massive sauropods The ten largest known dinosaurs by weight, based on published weight estimates.

- Amphicoelias: 122.4 t[1]

- Argentinosaurus: 73-88 t[2][3]

- Futalognkosaurus: (comparable to Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus)[4]

- Puertasaurus: (comparable to Argentinosaurus)[5]

- Antarctosaurus: 69 t[3]

- Paralititan: 59 t[2]

- Sauroposeidon: 50-60 t[6][7]

- Turiasaurus: 40-48 t[8]

- Supersaurus: 35-40 t[9]

- Diplodocus: 16-38 t[1][3]

Longest dinosaurs

See also Longest sauropods The ten longest known dinosaurs, based on published length estimates.

- Amphicoelias: 40–60 m (130–200 ft)[1]

- Argentinosaurus: 30–36 m (98–118 ft)?[1][10]

- Supersaurus: 33–34 m (108–112 ft)[9]

- Sauroposeidon: 28–34 m (92–112 ft)[1][6][7]

- Futalognkosaurus: 28–34 m (92–112 ft)[4][10]

- Diplodocus: 30–33.5 m (98–109.9 ft)[3][10]

- "Antarctosaurus" giganteus: 33 m (108 ft)?[10]

- Paralititan: 26–32 m (85–105 ft)[1][10]

- Turiasaurus: >30 m (98 ft)[8]

- Puertasaurus: 30 m (98 ft)?[10]

Lightest non-avialan dinosaurs

The ten smallest known non-avialan dinosaurs by weight, based on published weight estimates.

- Anchiornis: 110 g[11]

- Compsognathus: 0.26 kg-3.5 kg[12][13]

- Juravenator: 0.34 kg[13]

- Fruitadens: 0.50 kg-0.75 kg[14]

- Sinosauropteryx: 0.55 kg[13]

- Archaeopteryx: 0.8 kg-1 kg[15]

- Microraptor: 0.95 kg[16]

Shortest non-avialan dinosaurs

The ten shortest known non-avialan dinosaurs, based on published length estimates.

- Unnamed (BEXHM: 2008.14.1): 17–40 cm (6.7–16 in)[17]

- Parvicursor: 30 cm (12 in)[10]

- "Ornithomimus" minutus: 30 cm (12 in)[10]

- Palaeopteryx: 30 cm (12 in)?[10]

- Nqwebasaurus: 30 cm (0.98 ft)[13]

- Anchiornis: 34 cm (13 in)[11]

- Archaeopteryx: 40 cm (16 in)[10]

- Wellnhoferia: 45 cm (18 in)[10]

- Xixianykus: 50 cm (20 in)[10]

- Alwalkeria: 50 cm (20 in)?[10]

Theropods

Main article: TheropodaSizes are given with a range, where possible, of estimates that have not been contradicted by more recent studies. In cases where a range of currently accepted estimates exist, sources are given for the sources with the lowest and highest estimates, respectively, and only the highest values are given if these individual sources give a range of estimates.

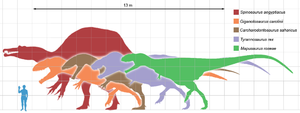

Longest theropods

Size by overall length, including tail, of all theropods over 12 meters.

- Spinosaurus: 14.3–18 m (47–59 ft)[13][18]

- Oxalaia: 12–14 m (39–46 ft)[19]

- Giganotosaurus: 12.5–13.2 m (41–43 ft)[10][12]

- Carcharodontosaurus: 12–13.2 m (39–43.3 ft)[13][20]

- Saurophaganax: 13 m (43 ft)[10]

- Chilantaisaurus: 13 m (43 ft)?[10]

- Tyrannosaurus: 12.8 m (42 ft)[21]

- Mapusaurus: 12.2–12.6 m (40–41 ft)[10][22]

- Tyrannotitan: 12.2 m (40 ft)[10]

- Torvosaurus: 12 m (39 ft)[10]

- Allosaurus: 12 m (39 ft)[10]

- Acrocanthosaurus: 12 m (39 ft)[10]

- Deinocheirus: 12 m (39 ft)?[10]

- Bahariasaurus: 12 m (39 ft)?[10][23]

Most massive theropods

Size by overall weight of all theropods with maximum weight estimates of over 4 metric tons.

- Spinosaurus: 7-20.9 t[13][18]

- Carcharodontosaurus: 6.1-15.1 t[12][13]

- Giganotosaurus: 6.5-13.8 t[12][13]

- Tyrannosaurus: 6-9.1 t[13][24]

- Bahariasaurus: (comparable to Tyrannosaurus)[23]

- Deinocheirus: ?9 t[25]

- Oxalaia: 5–7 t (5.5–7.7 short tons)[19]

- Acrocanthosaurus: 5.6-6.2 t[13][26]

- Suchomimus: 3.8-5.2 t[12][13]

- Tarbosaurus: 1.6-5 t[24][25]

Shortest non-avialan theropods

A list of all known non-avialan theropods with an adult length of under 90 centimeters, excluding soft tissue such as feathered tails.

- Unnamed (BEXHM: 2008.14.1): 17–40 cm (6.7–16 in)[17]

- Parvicursor: 30 cm (12 in)[10]

- "Ornithomimus" minutus: 30 cm (12 in)[10]

- Palaeopteryx: 30 cm (12 in)?[10]

- Nqwebasaurus: 30 cm (12 in)[13]

- Anchiornis: 34 cm (13 in)[11]

- Archaeopteryx: 40 cm (16 in)[10]

- Wellnhoferia: 45 cm (18 in)[10]

- Xixianykus: 50 cm (20 in)[10]

- Alwalkeria: 50 cm (20 in)?[10]

- Jinfengopteryx: 55 cm (1.80 ft)[27]

- Shuvuuia: 60 cm (2.0 ft)[10]

- Pedopenna: 60 cm (2.0 ft)?[10]

- Mahakala: 70 cm (2.3 ft)[28]

- Protarchaeopteryx: 70 cm (2.3 ft)[10]

- Rahonavis: 70 cm (2.3 ft)[10]

- Pneumatoraptor: 73 cm (2.40 ft)[29]

Least massive non-avialan theropods

A list of all known non-avialan theropods with an adult weight of 1 kilogram or less.

- Anchiornis: 110 g[11]

- Compsognathus: 0.26 kg-3.5 kg[12][13]

- Juravenator: 0.34 kg[13]

- Sinosauropteryx: 0.55 kg[13]

- Microraptor: 0.95 kg[16]

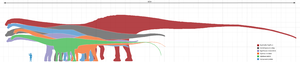

Sauropods

Main article: SauropodaSauropod size is difficult to estimate given their usually fragmentary state of preservation. Sauropods are often preserved without their tails, so the margin of error in overall length estimates is high. Mass is calculated using the cube of the length, so for species in which the length is particularly uncertain, the weight is even more so. Estimates that are particularly uncertain (due to very fragmentary or lost material) are preceded by a question mark. Each number represents the highest estimate of a given research paper.

Note that, generally, the giant sauropods can be divided into two categories: the shorter but stockier and more massive forms (mainly titanosaurs and some brachiosaurids), and the longer but slenderer and more light-weight forms (mainly diplodocids).

Longest sauropods

A list of sauropods that reached over 25 meters in length, including neck and tail.

- Amphicoelias: 40–60 m (130–200 ft)[1]

- Argentinosaurus: 30–36 m (98–118 ft)?[1][10]

- Supersaurus: 33–34 m (108–112 ft)[9]

- Futalognkosaurus: 28–34 m (92–112 ft)[4][10]

- Sauroposeidon: 28–34 m (92–112 ft)[1][6][7]

- Diplodocus: 30–33.5 m (98–109.9 ft)[3][10]

- "Antarctosaurus" giganteus: 33 m (108 ft)?[10]

- Paralititan: 26–32 m (85–105 ft)[1][10]

- Turiasaurus: >30 m (98 ft)[8]

- Puertasaurus: 30 m (98 ft)?[10]

- Hudiesaurus: 20–30 m (66–98 ft)[10][30]

- Argyrosaurus: 28 m (92 ft)[10]

- Barosaurus: 26 m (85 ft)[12]

- Brachiosaurus: 26 m (85 ft)[10]

- Apatosaurus: 22.8–26 m (75–85 ft)[3][10]

- Giraffatitan: 21.8–26 m (72–85 ft)[3][10]

- Tornieria: 26 m (85 ft)?[10]

- Mamenchisaurus: 20.4–26 m (67–85 ft)[3][10]

- Phuwiangosaurus: 25 m (82 ft)[10]

- Chuanjiesaurus: 25 m (82 ft)[10]

- "Cetiosaurus" humerocristatus: 25 m (82 ft)?[10]

Most massive sauropods

Size by overall weight of all sauropods over 20 metric tons.

- Amphicoelias: 122.4 t[1]

- Argentinosaurus: 73-88 t[2][3]

- Futalognkosaurus: (comparable to Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus)[4]

- Puertasaurus: (comparable to Argentinosaurus)[5]

- Paralititan: 59 t[2]

- Antarctosaurus: 69 t[3]

- Sauroposeidon: 50-60 t[6][7]

- Turiasaurus: 40-48 t[8]

- Supersaurus: 35-40 t[9]

- Diplodocus: 16-38 t[1][3]

- Brachiosaurus: 28.7-37 t[31][32]

- Giraffatitan: 23-39.5 t[3][31]

- Apatosaurus: 20.6 t[3]

- Barosaurus: 20 t[12]

Smallest sauropods

A list of all sauropods measuring 10 meters or less in length.

- Ohmdenosaurus: 4 m (13 ft)

- Blikanasaurus: 5 m (16 ft)

- Magyarosaurus: 5.3 m (17 ft)

- Europasaurus: 6 m (20 ft)

- Vulcanodon: 6.5 m (21 ft)

- Isanosaurus: 7 m (23 ft)

- Camelotia: 9 m (30 ft)

- Tazoudasaurus: 9 m (30 ft)

- Antetonitrus: 8–10 m (26–33 ft), 1.5–2 m (4.9–6.6 ft) tall at hip

- Shunosaurus: 10 m (33 ft)

- Brachytrachelopan: 10 m (33 ft)

- Amazonsaurus: 10 m (33 ft), 10 tons

Ornithopods

Main article: OrnithopodaLongest ornithopods

Size by overall length, including tail, of all ornithopods over 12 meters.

- Shantungosaurus: 15–16.6 m (49–54.5 ft)[10][33]

- "Lambeosaurus" laticaudus: 15–16.5 m (49–54.1 ft)[10][34]

- Hypsibema: 15 m (49 ft)?[10]

- Edmontosaurus: 12 m (39 ft)[35] to 13 m (43 ft)[36]

- Iguanodon: 10–13 m (33–43 ft)[10][37]

- Charonosaurus: 10–13 m (33–43 ft)[10][38]

- Anatotitan: 12 m (39 ft)[39]

- Olorotitan: 12 m (39 ft)[38]

- Saurolophus: 12 m (39 ft)[40]

- Ornithotarsus: 12 m (39 ft)?[10]

- Kritosaurus sp.: 11 m (36 ft)[41]

Most massive ornithopods

- "Lambeosaurus" laticaudus: up to 23 metric tons (25 short tons)[34]

- Shantungosaurus: up to 16 metric tons (17.6 short tons)[42]

- Edmontosaurus: 4.0 metric tons (4.4 short tons)[42]

- Hypacrosaurus: 4.0 metric tons (4.4 short tons)[42]

Ceratopsians

Main article: CeratopsiaLongest ceratopsians

Size of Triceratops compared to human.

Size of Triceratops compared to human.

Size by overall length, including tail, of all ceratopsians measuring 7 meters or more in length.

- Triceratops: 9 m (30 ft)[10]

- Torosaurus 9 m (30 ft)[10]

- Titanoceratops 9 m (30 ft)[10]

- Eotriceratops 9 m (30 ft)[10]

- Pachyrhinosaurus: 8 m (26 ft)[10]

- Pentaceratops: 8 m (26 ft)[10]

- Ojoceratops: 8 m (26 ft)[10]

- Coahuilaceratops: 8 m (26 ft)[10]

- Nedoceratops: 7.6 m (25 ft)[10]

- Vagaceratops: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Utahceratops: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Sinoceratops: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Mojoceratops: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Chasmosaurus: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Arrhinoceratops: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Agujaceratops: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

Smallest ceratopsians

A list of all ceratopsians 2 metres (6.6 ft) or less in length.

- Chaoyangsaurus: 60 cm (2.0 ft)[10]

- Graciliceratops: 60 cm (2.0 ft)[10]

- Xuanhuaceratops: 60 cm (2.0 ft)[10]

- Microceratus: 60 cm (2.0 ft)[10]

- Bagaceratops: 90 cm (3.0 ft)[10]

- Ajkaceratops: 1 m (3.3 ft)[43]

- Hongshanosaurus: 1.2 m (3.9 ft)[10]

- Protoceratops: 1.4 m (4.6 ft)[10]

- Archaeoceratops: 1.5 m (4.9 ft)[10]

- Yamaceratops: 1.5 m (4.9 ft)[10]

- Asiaceratops: 1.8 m (5.9 ft)[10]

- Cerasinops: 1.8 m (5.9 ft)[10]

- Leptoceratops: 1.8 m (5.9 ft)[10]

- Psittacosaurus: 1.8 m (5.9 ft)[10]

Pachycephalosaurs

Main article: PachycephalosauriaLongest pachycephalosaurs

- Pachycephalosaurus: 4.6 m (15 ft)

Smallest pachycephalosaurs

- Wannanosaurus: 60 cm (2.0 ft)

Thyreophorans

Main article: ThyreophoraLongest thyreophorans

Size by overall length, including tail, of all thyreophorans measuring 7 meters or more in length.

- Ankylosaurus: 6.25–10.7 m (20.5–35 ft)[44]

- Cedarpelta: 9.0 m (29.5 ft)[10]

- Stegosaurus: 9.0 m (29.5 ft)[10]

- Dacentrurus: 8 m (26 ft)[10]

- Tarchia: 8.0 m (26.2 ft)[10]

- Sauropelta: 7.6 m (25 ft)[10]

- Edmontonia: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Euoplocephalus: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Panoplosaurus: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Saichania: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Shamosaurus: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Tsagantegia: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Tuojiangosaurus: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Gigantspinosaurus: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Jiangjunosaurus: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Dyoplosaurus: 7 m (23 ft)[10]

- Hypsirophus: 7 m (23 ft)?[10]

Smallest thyreophorans

- Scutellosaurus: 1.2 m (3.9 ft)[10]

- Dracopelta: 2 m (6.6 ft)[10]

- Minmi: 2 m (6.6 ft)[10]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; and Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36. Albuquerque: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

- ^ a b c d Burness, G.P.; Flannery, T.; Flannery, T (2001). "Dinosaurs, dragons, and dwarfs: The evolution of maximal body size". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 (25): 14518–14523. doi:10.1073/pnas.251548698. PMC 64714. PMID 11724953. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=64714.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mazzetta, G.V.; Christiansen, P.; Farina, R.A. (2004). "Giants and bizarres: body size of some southern South American Cretaceous dinosaurs". Historical Biology 2004: 1–13.

- ^ a b c d Calvo, J.O., Porfiri, J.D., González-Riga, B.J., and Kellner, A.W. (2007) "A new Cretaceous terrestrial ecosystem from Gondwana with the description of a new sauropod dinosaur". Anais Academia Brasileira Ciencia, 79(3): 529-41.[1]

- ^ a b Novas, Fernando E.; Salgado, Leonardo; Calvo, Jorge; and Agnolin, Federico (2005). "Giant titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia". Revisto del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, n.s. 7 (1): 37–41. http://www.macn.secyt.gov.ar/cont_Publicaciones/Rns-Vol07-1_37-41.pdf. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- ^ a b c d Wedel, Mathew J.; Cifelli, Richard L. (Summer 2005). "Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma's Native Giant" (PDF). Oklahoma Geology Notes 65 (2): 40–57. http://sauroposeidon.net/Wedel-Cifelli_2005_native-giant.pdf.

- ^ a b c d Wedel, Mathew J.; Cifelli, Richard L.; Sanders, R. Kent (2000). "Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur Sauroposeidon" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 45: 343–3888. http://sauroposeidon.net/Wedel-et-al_2000b_sauroposeidon.pdf.

- ^ a b c d Royo-Torres, R.; Cobos, A.; Alcalá, L. (2006). "A Giant European Dinosaur and a New Sauropod Clade". Science 314 (5807): 1925–1927. doi:10.1126/science.1132885. PMID 17185599.

- ^ a b c d Lovelace, David M.; Hartman, Scott A.; and Wahl, William R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny". Arquivos do Museu Nacional 65 (4): 527–544.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.

- ^ a b c d Xu, X., Zhao, Q., Norell, M., Sullivan, C., Hone, D., Erickson, G., Wang, X., Han, F. and Guo, Y. (2009). "A new feathered maniraptoran dinosaur fossil that fills a morphological gap in avian origin." Chinese Science Bulletin, 6 pages, accepted November 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Seebacher, F. (2001). "A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Therrien, F.; and Henderson, D.M. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Butler, R.J., P.M. Galton, L.B. Porro, L.M. Chiappe, D.M. Henderson, and G.M. Erickson. (2009). "Lower limits of ornithischian dinosaur body size inferred from a new Upper Jurassic heterodontosaurid from North America." Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 10.1098/rspb.2009.1494

- ^ Erickson, Gregory M.; Rauhut, Oliver W. M., Zhou, Zhonghe, Turner, Alan H, Inouye, Brian D. Hu, Dongyu, Norell, Mark A. (2009). "Was Dinosaurian Physiology Inherited by Birds? Reconciling Slow Growth in Archaeopteryx". PLoS One 4 (10): e7390. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007390. PMC 2756958. PMID 19816582. http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0007390;jsessionid=F7E462DE00439EEA45BCC1AF96012EE0. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ a b Chatterjee, S., and Templin, R.J. (2007). "Biplane wing planform and flight performance of the feathered dinosaur Microraptor gui." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(5): 1576-1580. [2]

- ^ a b Naish, D. and Sweetman, S.C. (2011). "A tiny maniraptoran dinosaur in the Lower Cretaceous Hastings Group: evidence from a new vertebrate-bearing locality in south-east England." Cretaceous Research, 32: 464-471. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.03.001

- ^ a b dal Sasso, C.; Maganuco, S.; Buffetaut, E.; and Mendez, M.A. (2005). "New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (4): 888–896. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0888:NIOTSO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. http://www.bioone.org/perlserv/?request=get-abstract&doi=10.1671%2F0272-4634%282005%29025%5B0888%3ANIOTSO%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

- ^ a b Kellner, Alexander W.A.; Sergio A.K. Azevedeo, Elaine B. Machado, Luciana B. Carvalho and Deise D.R. Henriques (2011). "A new dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Alcântara Formation, Cajual Island, Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 83 (1): 99–108. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100006. ISSN 0001-3765. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/aabc/v83n1/v83n1a06.pdf.

- ^ Sereno, P. C.; Dutheil, D. B.; Iarochene, M.; Larsson, H. C. E.; Lyon, G. H.; Magwene, P. M.; Sidor, C. A.; Varricchio, D. J. et al. (1996). "Predatory dinosaurs from the Sahara and the Late Cretaceous faunal differentiation". Science 272 (5264): 986–991. doi:10.1126/science.272.5264.986. PMID 8662584.

- ^ Henderson DM (January 1, 1999). "Estimating the masses and centers of mass of extinct animals by 3-D mathematical slicing". Paleobiology 25 (1): 88–106. http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/25/1/88.

- ^ Coria, R. A.; Currie, P. J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina". Geodiversitas 28 (1): 71–118. http://www.mnhn.fr/museum/front/medias/publication/7653_g06n1a4.pdf.

- ^ a b Smith, J.B.; Lamanna, M.C.; Lacovara, K.J.; Dodson, P.; Smith, J.R.; Poole, J.C.; Giegengack, R.; and Attia, Y. (2001). "A Giant sauropod dinosaur from an Upper Cretaceous mangrove deposit in Egypt". Science 292 (5522): 1704–1706. doi:10.1126/science.1060561. PMID 11387472.

- ^ a b Christiansen, P.; Fariña, R.A. (2004). "Mass prediction in theropod dinosaurs". Historical Biology 16: 85–92. doi:10.1080/08912960412331284313.

- ^ a b Valkenburgh, B.; Molnar, R.E. (2002). "Dinosaurian and mammalian predators compared". Paleobiology 28 (4): 527–543. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2002)028<0527:DAMPC>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ^ Bates, K.T., Manning, P.L., Hodgetts, D. and Sellers, W.I. (2009). "Estimating Mass Properties of Dinosaurs Using Laser Imaging and 3D Computer Modelling." PLoS ONE, 4(2): e4532. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004532 Online full text.

- ^ Ji, Q.; Ji, S.; Lu, J.; You, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. (2005). "First avialan bird from China (Jinfengopteryx elegans gen. et sp. nov.)". Geological Bulletin of China 24 (3): 197–205.

- ^ Turner, Alan H.; Pol, Diego; Clarke, Julia A.; Erickson, Gregory M.; and Norell, Mark (2007). "A basal dromaeosaurid and size evolution preceding avian flight" (pdf). Science 317 (5843): 1378–1381. doi:10.1126/science.1144066. PMID 17823350. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/reprint/317/5843/1378.pdf.

- ^ Ősi, A., Apesteguía, S.M and Kowalewski, M. (In press). "Non-avian theropod dinosaurs from the early Late Cretaceous of Central Europe." Cretaceous Research, doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.01.001

- ^ Dong, Z. (1997). "A gigantic sauropod (Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum gen. et sp. nov.) from the Turpan Basin, China." Pp. 102-110 in Dong, Z. (ed.), Sino-Japanese Silk Road Dinosaur Expedition. China Ocean Press, Beijing.

- ^ a b Taylor, M.P. (2009). "A Re-evaluation of Brachiosaurus altithorax Riggs 1903 (Dinosauria, Sauropod) and its generic separation from Giraffatitan brancai (Janensh 1914)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (3): 787–806. doi:10.1671/039.029.0309.

- ^ Christiansen, P. (1997). "Feeding mechanisms of the sauropod dinosaurs Brachiosaurus, Camarasaurus, Diplodocus and Dicraeosaurus". Historical Biology 14 (3): 137–152. doi:10.1080/10292380009380563.

- ^ Zhao, X.; Li, D.; Han, G.; Hao, H.; Liu, F.; Li, L.; and Fang, X. (2007). "Zhuchengosaurus maximus from Shandong Province". Acta Geoscientia Sinica 28 (2): 111–122. doi:10.1007/s10114-005-0808-x.

- ^ a b Morris, William J. (1981). "A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Baja California: ?Lambeosaurus laticaudus". Journal of Paleontology 55 (2): 453–462. Note that the size estimate given in this paper is actually for LACM 26757, not definitively assigned to ?L. laticaudus.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Edmontosaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 389–396. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ Lambert, David; and the Diagram Group (1990). The Dinosaur Data Book. New York: Avon Books. p. 60. ISBN 0-380-75896-3.

- ^ Naish, Darren; David M. Martill (2001). "Ornithopod dinosaurs". Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. London: The Palaeontological Association. pp. 60–132. ISBN 0-901702-72-2.

- ^ a b Dixon, Dougal (2006). The Complete Book of Dinosaurs. London: Anness Publishing Ltd.. p. 216. ISBN 0-681-37578-7.

- ^ Sues, Hans-Dieter (1997). "ornithopods". In James Orville Farlow and M. K. Brett-Surman (eds.). The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 338. ISBN 0-253-33349-0.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Saurolophus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 788–789. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ Kirkland, James I.; Hernández-Rivera, René; Gates, Terry; Paul, Gregory S.; Nesbitt, Sterling; Serrano-Brañas, Claudia Inés; and Garcia-de la Garza, Juan Pablo (2006). "Large hadrosaurine dinosaurs from the latest Campanian of Coahuila, Mexico". In Lucas, S.G.; and Sullivan, Robert M. (eds.). Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 35. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 299–315.

- ^ a b c Horner, John R.; Weishampel, David B.; and Forster, Catherine A (2004). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 438–463. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ Ősi, Attila; Butler, R.J.; Weishampel, David B. (2010-05-27). "A Late Cretaceous ceratopsian dinosaur from Europe with Asian affinities". Nature 465 (7297): 466–468. doi:10.1038/nature09019. PMID 20505726.

- ^ Carpenter, K. (2004). "Redescription of Ankylosaurus magniventris Brown 1908 (Ankylosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Western Interior of North America". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 41 (8): 961–986. doi:10.1139/e04-043.

- Paul, Gregory S. (1997). "Dinosaur models: the good, the bad, and using them to estimate the mass of dinosaurs". Dinofest International 1997: 129–154.

External links

Categories:- Dinosaurs

- Size

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.