- Boston Molasses Disaster

-

The Boston Molasses Disaster, also known as the Great Molasses Flood and the Great Boston Molasses Tragedy, occurred on January 15, 1919, in the North End neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts in the United States. A large molasses storage tank burst, and a wave of molasses rushed through the streets at an estimated 35 mph (56 km/h), killing 21 and injuring 150. The event has entered local folklore, and residents claim that on hot summer days, the area still smells of molasses.[1]

Contents

Disaster

The disaster occurred at the Purity Distilling Company facility on January 15, 1919, an unusually warm day for January (40˚ F, 4.4˚ C). At the time, molasses was the standard sweetener in the United States. Molasses can also be fermented to produce rum and ethyl alcohol, the active ingredient in other alcoholic beverages and a key component in the manufacturing of munitions at the time.[2] The stored molasses was awaiting transfer to the Purity plant situated between Willow Street and what is now named Evereteze Way, in Cambridge.

Near Keany Square,[3] at 529 Commercial Street, a huge molasses tank 50 ft (15 m) tall, 90 ft (27 m) in diameter and containing as much as 2,300,000 US gal (8,700 m3) collapsed. Witnesses stated that as it collapsed, there was a loud rumbling sound, like a machine gun as the rivets shot out of the tank, and that the ground shook as if a train were passing by.[4]

The collapse unleashed an immense wave of molasses between 8 and 15 ft (2.5 and 4.5 m) high, moving at 35 mph (56 km/h), and exerting a pressure of 2 ton/ft² (200 kPa).[5] The molasses wave was of sufficient force to break the girders of the adjacent Boston Elevated Railway's Atlantic Avenue structure and lift a train off the tracks. Nearby, buildings were swept off their foundations and crushed. Several blocks were flooded to a depth of 2 to 3 feet (60 to 90 cm). As described by author Stephen Puleo:

-

Molasses, waist deep, covered the street and swirled and bubbled about the wreckage. Here and there struggled a form — whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell. Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass, showed where any life was... Horses died like so many flies on sticky fly-paper. The more they struggled, the deeper in the mess they were ensnared. Human beings — men and women — suffered likewise.[6]

The Boston Globe reported that people "were picked up by a rush of air and hurled many feet." Others had debris hurled at them from the rush of sweet-smelling air. A truck was picked up and hurled into Boston Harbor. Approximately 150 were injured; 21 people and several horses were killed — some were crushed and drowned by the molasses. The wounded included people, horses, and dogs; coughing fits became one of the most common ailments after the initial blast.

-

Anthony di Stasio, walking homeward with his sisters from the Michelangelo School, was picked up by the wave and carried, tumbling on its crest, almost as though he were surfing. Then he grounded and the molasses rolled him like a pebble as the wave diminished. He heard his mother call his name and couldn't answer, his throat was so clogged with the smothering goo. He passed out, then opened his eyes to find three of his sisters staring at him.[1]

Aftermath

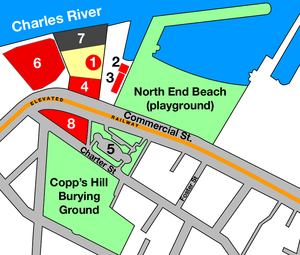

Detail of molasses flood area. 1. Purity Distilling molasses tank 2. Firehouse 31 (heavy damage) 3. Paving department and police station 4. Purity offices (flattened) 5. Copps Hill Terrace 6. Boston Gas Light building (damaged) 7. Purity warehouse (mostly intact) 8. Residential area (site of flattened Clougherty house)

Detail of molasses flood area. 1. Purity Distilling molasses tank 2. Firehouse 31 (heavy damage) 3. Paving department and police station 4. Purity offices (flattened) 5. Copps Hill Terrace 6. Boston Gas Light building (damaged) 7. Purity warehouse (mostly intact) 8. Residential area (site of flattened Clougherty house)

First to the scene were 116 cadets under the direction of Lieutenant Commander H. J. Copeland from USS Nantucket, a training ship of the Massachusetts Nautical School (which is now the Massachusetts Maritime Academy), that was docked nearby at the playground pier.[3] They ran several blocks toward the accident. They worked to keep the curious from getting in the way of the rescuers while others entered into the knee-deep sticky mess to pull out the survivors. Soon the Boston Police, Red Cross, Army and other Navy personnel arrived. Some nurses from the Red Cross dove into the molasses, while others tended to the wounded, keeping them warm as well as keeping the exhausted workers fed. Many of these people worked through the night. The injured were so numerous that doctors and surgeons set up a makeshift hospital in a nearby building. Rescuers found it difficult to make their way through the syrup to help the victims. It took four days before they stopped searching for victims; many dead were so glazed over in molasses, they were hard to recognize.

Cleanup

The cleanup took only about two weeks because of the large number of helping hands.[citation needed] It took over 87,000 man hours (roughly the number of hours in ten years) to remove the molasses from the cobblestone streets, theaters, businesses, automobiles, and homes.[6] The harbor was still brown with molasses until summer.

United States Industrial Alcohol did not rebuild the tank. The property became a yard for the Boston Elevated Railway (predecessor to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority), and is currently the site of a city-owned baseball field.

Causes

Local residents brought a class-action lawsuit, one of the first held in Massachusetts, against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company (USIA), which had bought Purity Distilling in 1917. In spite of the company's attempts to claim that the tank had been blown up by anarchists[7] (because some of the alcohol produced was to be used in making munitions), a court-appointed auditor found USIA responsible after three years of hearings. United States Industrial Alcohol Company ultimately paid out $600,000 in out-of-court settlements (at least $6.6 million in 2005 dollars).[8]

Several factors that occurred on that day and the previous days might have contributed to the disaster. The tank was constructed poorly and tested insufficiently. Due to fermentation occurring within the tank, carbon dioxide production might have raised the internal pressure. The rise in local temperatures that occurred over the previous day also would have assisted in building this pressure. Records show that the air temperature rose from 2°F to 41°F (from −17°C to 5°C) over that period. The failure occurred from a manhole cover near the base of the tank, and it is possible that a fatigue crack there grew to the point of criticality. The hoop stress is greatest near the base of a filled cylindrical tank. The tank had only been filled to capacity eight times since it was built a few years previously, putting the walls under an intermittent, cyclical load.

An inquiry after the disaster revealed that Arthur Jell, who oversaw the construction, neglected basic safety tests, such as filling the tank with water to check for leaks. When filled with molasses, the tank leaked so badly that it was painted brown to hide the leaks. Local residents collected leaked molasses for their homes.[8]

An urban legend claims that the doomed tank might have been overfilled in late 1918 so that the owners could produce as much rum as possible before Prohibition came into effect. However, Purity Distilling did not make rum, but rather specialized in the production of industrial alcohol, which was exempt from the state prohibition laws in effect in 1919, and would later be exempted from the Volstead Act and other national Prohibition laws. While an urban legend, a 1999 television documentary, part of the Modern Marvels' Engineering Disasters sub-series, argued that—even if there was no specific plan to make alcohol to beat Prohibition—there may have been some general idea of increasing the volume at the last minute so as to prepare in case alcohol prohibition might occur.

Fatalities

[9][3]Name Age Occupation Patrick Breen 44 Laborer (North End Paving Yard) William Brogan 61 Teamster Bridget Clougherty 65 Homemaker Stephen Clougherty 34 Unemployed John Callahan 43 Paver (North End Paving Yard) Maria Distasio 10 Child William Duffy 58 Laborer (North End Paving Yard) Peter Francis 64 Blacksmith (North End Paving Yard) Flaminio Gallerani 37 Driver Pasquale Iantosca 10 Child James H. Kinneally Unknown Laborer (North End Paving Yard) Eric Laird 17 Teamster George Layhe 38 Firefighter (Engine 31) James Lennon 64 Teamster/Motorman Ralph Martin 21 Driver James McMullen 46 Foreman, Bay State Express Cesar Nicolo 32 Expressman Thomas Noonan 43 Longshoreman Peter Shaughnessy 18 Teamster John M. Seiberlich 69 Blacksmith (North End Paving Yard) Michael Sinnott 76 Messenger Today

The sites of the molasses tank and the North End Paving Company have been turned into a recreational complex, officially named Langone Park, featuring a Little League ballfield, a playground, and bocce courts.[10] Immediately to the east is the larger Puopolo Park, with additional recreational facilities.[11]

A small plaque at the entrance to Puopolo Park, placed by the Bostonian Society, commemorates the disaster.[12] The plaque, entitled "Boston Molasses Flood", reads:

-

On January 15, 1919, a molasses tank at 529 Commercial Street exploded under pressure, killing 21 people. A 40-foot wave of molasses buckled the elevated railroad tracks, crushed buildings and inundated the neighborhood. Structural defects in the tank combined with unseasonably warm temperatures contributed to the disaster.

Drivers on Boston's Old Town Trolley and other tour services often read off accounts of the accident to their passengers, sometimes referring to it by the neologism "The Boston Molassacre".[citation needed]

See also

General reference

- Puleo, Stephen (2004). Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5021-0.

Notes

- ^ a b Park, Edwards (24 November 2004). "Eric Postpischil's Molasses Disaster Pages, Smithsonian Article". Eric Postpischil's Domain (Smithsonian Institution) 14 (8): 213–230. http://edp.org/molpark.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ Puleo, Stephen, "Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919", page 11. Beacon Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8070-5021-0

- ^ a b c "12 Killed When Tank of Molasses Explodes" (PDF). The New York Times: pp. 4. January 15, 1919. January 16, 1919. ISSN 1553395. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9B04E4D71339E13ABC4E52DFB7668382609EDE&oref=slogin. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ^ "Great Molasses Flood". Massachusetts foundation for the Humanities. http://www.massmoments.org/moment.cfm?mid=19. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ "The Great Molasses Flood of 1919". The Ooze. http://www.ooze.com/ooze6/X0024_The_Great_Flood.html. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ a b Puleo, Stephen, "Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919", page 98. Beacon Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8070-5021-0

- ^ "What caused the great Boston Molasses Flood?". The Massachusetts Historical Society. http://www.masshist.org/library/faqs.cfm#flood. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ^ a b "Was Boston once literally flooded with molasses?". The Straight Dope. The Chicago Reader. http://www.straightdope.com/columns/041231.html. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ Puleo, Stephen, “Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919”, page 239. Beacon Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8070-5021-0

- ^ City parks

- ^ Places to go

- ^ Boston On-Line: Disasters

External links

- Boston Public Library. Photos related to the event on Flickr. Many phrases are direct quotes.

- Listen online - The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 - The American Storyteller Radio Journal

- What caused the great Boston Molasses Flood? from the Massachusetts Historical Society

- "The Molasses Disaster of January 15, 1919", reprinted from Yankee Magazine

- An interview with Stephen Puleo, author of the book listed in References section above

- Molasses flood site, present-day pictures and list of 1919 inhabitants, at archive.org

- Hiatt Harlow, Joan. "Joshua's Song". http://mysite.verizon.net/sevenjays1/JoshuasSong.htm., children's book (fiction) centered upon the incident

- "Molasses", sea shanty based on the incident and the history of molasses. Attributed to Tom Rowe of the Schooner Fare and Turkey Hollow folk music groups.

- "Were You In Boston in 1919?", folk song about the incident.

- Molasses Flood of 1919

- Washington Times January 18, 1919

Coordinates: 42°22′06.6″N 71°03′21.0″W / 42.3685°N 71.05583°W

Categories:- Environmental disasters in the United States

- 1919 disasters

- 1919 in Massachusetts

- History of Boston, Massachusetts

- 20th century in Boston, Massachusetts

- Industrial accidents and incidents

- Disasters in Massachusetts

- North End, Boston

- Engineering failures

- Massachusetts in the 1910s

-

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.