- Memento mori

-

Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation by Hans Memling. This triptych contrasts earthly beauty and luxury with the prospect of death and hell.

Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation by Hans Memling. This triptych contrasts earthly beauty and luxury with the prospect of death and hell.

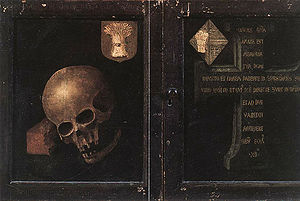

The outer panels of Rogier van der Weyden's Braque Triptych shows the skull of the patron displayed in the inner panels. The bones rest on a brick, a symbol of his former industry and achievement.[1]

The outer panels of Rogier van der Weyden's Braque Triptych shows the skull of the patron displayed in the inner panels. The bones rest on a brick, a symbol of his former industry and achievement.[1]

Memento mori is a Latin phrase translated as "Remember your mortality", "Remember you must die" or "Remember you will die".[2] It names a genre of artistic work which varies widely, but which all share the same purpose: to remind people of their own mortality. The phrase has a tradition in art that dates back to antiquity.

Contents

Historic usage

Classical

In ancient Rome, the words are believed to have been used on the occasions when a Roman general was parading through the streets during a victory triumph. Standing behind the victorious general was his slave, who was tasked to remind the general that, though his highness was at his peak today, tomorrow he could fall or, more likely, be brought down. The servant conveyed this by telling the general that he should remember, "Memento mori." It is further possible that the servant said instead, "Respice post te! Hominem te esse memento! Memento mori!": "Look behind you! Remember that you are but a man! Remember that you'll die!", as noted by Tertullian in his Apologeticus.[3]

Medieval Europe

The thought came into its own with Christianity, whose strong emphasis on Divine Judgment, Heaven, Hell, and the salvation of the soul brought death to the forefront of consciousness. Most memento mori works are products of Christian art, although there are equivalents in Buddhist art. In the Christian context, the memento mori acquires a moralizing purpose quite opposed to the Nunc est bibendum theme of Classical antiquity. To the Christian, the prospect of death serves to emphasize the emptiness and fleetingness of earthly pleasures, luxuries, and achievements, and thus also as an invitation to focus one's thoughts on the prospect of the afterlife. A Biblical injunction often associated with the memento mori in this context is In omnibus operibus tuis memorare novissima tua, et in aeternum non peccabis (the Vulgate's Latin rendering of Ecclesiasticus 7:40, "in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin.") This finds ritual expression in the Catholic rites of Ash Wednesday when ashes are placed upon the worshipers' heads with the words "Remember Man that you are dust and unto dust you shall return."

The most obvious places to look for memento mori meditations are in funeral art and architecture. Perhaps the most striking to contemporary minds is the transi, or cadaver tomb, a tomb which depicts the decayed corpse of the deceased. This became a fashion in the tombs of the wealthy in the fifteenth century, and surviving examples still create a stark reminder of the vanity of earthly riches. The famous danse macabre, with its dancing depiction of the Grim Reaper carrying off rich and poor alike, is another well known example of the memento mori theme. This and similar depictions of Death decorated many European churches. Later, Puritan tomb stones in the colonial United States frequently depicted winged skulls, skeletons, or angels snuffing out candles. These are among the numerous themes associated with skull imagery.

Timepieces were formerly an apt reminder that your time on earth grows shorter with each passing minute. Public clocks would be decorated with mottos such as ultima forsan ("perhaps the last" [hour]) or vulnerant omnes, ultima necat ("they all wound, and the last kills"). Even today, clocks often carry the motto tempus fugit, "time flies." Old striking clocks often sported automata who would appear and strike the hour; some of the celebrated automaton clocks from Augsburg, Germany had Death striking the hour. The several computerized "death clocks" revive this old idea. Private people carried smaller reminders of their own mortality. Mary, Queen of Scots, owned a large watch carved in the form of a silver skull, embellished with the lines of Horace.

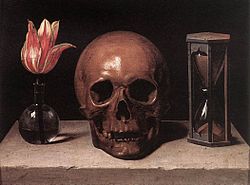

A version of the theme in the artistic genre of still life is more often referred to as a vanitas, Latin for "vanity". These include symbols of mortality, whether obvious ones like skulls, or more subtle ones, like a flower losing its petals. See the themes associated with the image of the skull.

After the invention of photography, many people had photographs taken of recently dead family members; given the technical limitations of daguerreotype photography, this was one way to get the portrait subject to sit still.

Memento mori was also an important literary theme. Well known literary meditations on death in English prose include Sir Thomas Browne's Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial and Jeremy Taylor's Holy Living and Holy Dying. These works were part of a Jacobean cult of melancholia that marked the end of the Elizabethan era. In the late eighteenth century, literary elegies were a common genre; Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard and Edward Young's Night Thoughts were typical members of the genre.

Prince of Orange René de Châlons died in 1544, at age 25. His widow commissioned sculptor Ligier Richier to represent him offering his heart to God, set against the painted splendour of his former worldly estate. Church of Saint-Étienne, Bar-le-Duc.

Prince of Orange René de Châlons died in 1544, at age 25. His widow commissioned sculptor Ligier Richier to represent him offering his heart to God, set against the painted splendour of his former worldly estate. Church of Saint-Étienne, Bar-le-Duc.

Apart from the genre of requiem and funeral music there is also a rich tradition of memento mori in the Early Music of Europe. Especially those facing the ever present death during the recurring bubonic plague pandemics from the 1340s onward tried to toughen themselves by anticipating the inevitable in chants, from the simple Geisslerlieder of the Flagellant movement to the more refined cloistral or courtly songs. The lyrics often looked at life as a necessary and god-given vale of tears with death as a ransom and reminded people to lead sinless lives to stand a chance at Judgement Day. Two stanzas typical of memento mori in mediaeval music are from the virelai ad mortem festinamus of the Catalan Llibre Vermell de Montserrat from 1399:

- Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur,

- Mors venit velociter quae neminem veretur,

- Omnia mors perimit et nulli miseretur.

- Ad mortem festinamus peccare desistamus.

- Life is short, and shortly it will end;

- Death comes quickly and respects no one,

- Death destroys everything and takes pity on no one.

- To death we are hastening, let us refrain from sinning.

- Ni conversus fueris et sicut puer factus

- Et vitam mutaveris in meliores actus,

- Intrare non poteris regnum Dei beatus.

- Ad mortem festinamus peccare desistamus.

- If you do not turn back and become like a child,

- And change your life for the better,

- You will not be able to enter, blessed, the Kingdom of God.

- To death we are hastening, let us refrain from sinning.

Much memento mori art is associated with the Mexican festival, Day of the Dead, including even skull-shaped candies, and bread loaves adorned with bread "bones". It was also famously expressed in the works of the Mexican engraver José Guadalupe Posada, in which various walks of life are depicted as skeletons.

Another example of memento mori is provided by the chapels of bones, such as the Capela dos Ossos in Évora or the Capuchin Crypt in Rome. These are chapels where the walls are totally or partially covered by human remains, mostly bones. The entrance to the former has the sentence "We bones, lying here bare, await for yours".

The motto of the French village of Èze is the phrase: "Moriendo Renascor" (meaning "In death I am Reborn") and its emblem is a phoenix perched on a bone.

Puritan America

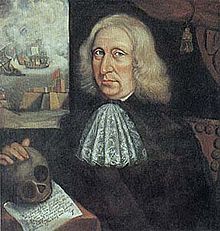

Colonial American art saw a large number of "memento mori" images due to Puritan influence. The Puritan community in 17th century North America looked down upon art because they believed it drew the faithful away from God, and if away from God, then it could only lead to the devil. However, portraits were considered historical records, and as such they were allowed. Thomas Smith, a 17th century Puritan, fought in many naval battles, and also painted. In his self-portrait we see a typical puritan "memento mori" with a skull, suggesting his imminent death.

The poem under the skull emphasizes Smith's acceptance of death:

Why why should I the World be minding, Therein a World of Evils Finding. Then Farwell World: Farwell thy jarres, thy Joies thy Toies thy Wiles thy Warrs. Truth Sounds Retreat: I am not sorye. The Eternall Drawes to him my heart, By Faith (which can thy Force Subvert) To Crowne me (after Grace) with Glory.

See also

References

- ^ Campbell, Lorne. Van der Weyden. London: Chaucer Press, 2004. 89. ISBN 1-90444-9247

- ^ literally " [in the future] remember to die", since "memento" is a future imperative of the 2nd person, and mori is a deponent infinitive.

- ^ Apologeticus, Chapter 33,4.

External links

- Isaiah 22

- Apologeticus

- Memento mori and vanitas elements in the funerary art at St. John's Co-Cathedral, Valetta, Malta, an article on memento mori and ars moriendi appearing in the journal "Treasures of Malta", December 2004.

Death and related topics In medicine Abortion · Autopsy · Brain death · Clinical death · End-of-life care · Euthanasia · Lazarus syndrome · Terminal illness · Mortal woundLists Causes of death by rate · Expressions related to death · Natural disasters · People by cause of death · Premature obituaries · Preventable causes of death · Notable deaths in 2007 · Notable deaths in 2008 · Notable deaths in 2009 · Notable deaths in 2010 · Unusual deathsMortality After death Body: Burial · Coffin birth · Cremation · Cryonics · Decomposition · Disposal · Mummification · Promession · Putrefaction · Resomation

Other: Afterlife · Cemetery · Customs · Death certificate · Funeral · Grief · Intermediate state · Mourning · VigilParanormal Legal Other Death and culture · Death (personification) · Fascination with death · Genocide · Last Rites · Martyr · Moribundity · Sacrifice (Human · Animal) · Suicide · Assisted suicide · Thanatology · War Death PortalCategories:

Death PortalCategories:- Iconography

- Art genres

- Latin mottos

- Latin words and phrases

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.