- Roman triumph

-

Trajan's column, a depiction in stone of a symbolic triumph celebrating Trajan's victory over the Dacians (Romania). The procession winds up the column in a spiral panel.

Trajan's column, a depiction in stone of a symbolic triumph celebrating Trajan's victory over the Dacians (Romania). The procession winds up the column in a spiral panel.

The Roman triumph (triumphus) was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the military achievement of an army commander who had won great military successes, or originally and traditionally, one who had successfully completed a foreign war. In Republican tradition, only the Senate could grant a triumph. The origins and development of this honour were obscure: Roman historians placed the first triumph in the mythical past.

On the day of his triumph, the general wore regalia that identified him as near-divine or near-kingly. He rode in a chariot through the streets of Rome in unarmed procession with his army and the spoils of his war. At Jupiter's temple on the Capitoline Hill he offered sacrifice and the tokens of his victory to the god. Thereafter he had the right to be described as vir triumphalis ("man of triumph", later known as triumphator) for the rest of his life. After death, he was represented at his own funeral, and those of his later descendants, by a hired actor who wore his death mask (imago) and was clad in the all-purple, gold-embroidered triumphal toga picta ("painted" toga).

Republican morality required that despite these extraordinary honours, the triumphator conduct himself with dignified humility, as a mortal citizen who triumphed on behalf of Rome's Senate, people and gods. Inevitably, besides its religious and military dimensions, the triumph offered extraordinary opportunities for self-publicity. As Roman territories expanded during the early and middle Republican eras, foreign wars increased the opportunities for self-promotion. While most Roman festivals were calendar fixtures, the tradition and law that reserved a triumph to extraordinary victory ensured that its celebration, procession and attendant feasting and public games promoted the status, achievements and person of the triumphator. These could be further celebrated and commemorated by his personal issue of triumphal coinage, and his funding of monumental public works and temples. By the Late Republican era, increasing competition among the competitive military-political adventurers who ran Rome's nascent empire ensured that triumphs became more frequent, drawn out and extravagant, prolonged in some cases by several days of public games and entertainments. From the Principate onwards, the Triumph reflected the Imperial order and the pre-eminence of the Imperial family.

Most Roman accounts of triumphs were written to provide their readers with a moral lesson, rather than to provide an accurate description of the triumphal process, procession, rites and their meaning. This scarcity allows for only the most tentative and generalised, and possibly misleading reconstruction of triumphal ceremony, based on the combination of various incomplete accounts from different periods of Roman history. Nevertheless, the triumph is considered a characteristically Roman ceremony which represented Roman wealth, power and grandeur, and has been consciously imitated by medieval and later states.

Contents

Background

The vir triumphalis

In Pre-Republican and Republican Rome, truly exceptional military achievement merited the highest possible honours, which connected the vir triumphalis ("man of triumph", later known as a triumphator) to Rome's mythical and semi-mythical past. In effect, vir triumphalis was close to being "king for a day", and possibly close to divinity. He wore the regalia traditionally associated both with the ancient Roman monarchy and with the statue of Jupiter Capitolinus: the purple and gold "toga picta", laurel crown, red boots and (again, possibly) the reddened face of Rome's supreme deity. From the time of Scipio Africanus, he was linked - at least in the opinion of historians during the Principate - to both Alexander and to the demi-god Hercules, who had laboured selflessly for the benefit of all mankind.[1][2][3]

Many Roman historians, and some moderns, presume that Rome's sense of conservatism and continuity would have preserved the essentials and meaning of the Triumphal rite from the days of Rome's foundation; for most Romans, the mythic antiquity of ritual confirmed its sanctity. The exclamation TRIVMPE which accompanied the triumphal rite was attested in the Carmen Arvale; to Romans of the later Republic, this ancient religious chant was probably as obscure in meaning as it is to modern scholarship. Roman etymologists thought it a borrowing via Etruscan from the Greek thriambus (θρίαμβος). Plutarch (and other Roman sources) accorded the first Roman triumph to Romulus, in celebration of his victory over King Acron of the Caeninenses, traditionally coeval with Rome's foundation in 753 BCE: this was held to explain the unique ritual costume of the vir triumphalis.[4] Ovid projected a fabulous and poetic triumphal precedent; the god Bacchus/Dionysus had returned in triumph from his conquest of India, drawn in a golden chariot by tigers and surrounded by maenads, satyrs and assorted drunkards.[5][6][7] Arrian attributed Dionysian and "Roman" elements to a victory procession of Alexander the Great.[8] No physical evidence survives for triumphal practice in the pre-Republican era.

Development in the Republic

In the Middle to Late Republic, the triumph was increasingly exploited by political-military adventurers. Accounts from this time combine nostalgia for Rome's vanished and virtuous past with fears for its future. Beard notes that the decline of the "peasant virtues" of ancient Rome was said to match the growth in triumphal ostentation.[9] Dionysius of Halicarnassus' imaginative account of Romulus' triumph (almost certainly informed by equally nostalgic Roman sources) led him to reflect that the triumphs of his own day (Ca 60 BCE – after 7 BCE) "departed in every respect from the ancient tradition of frugality".[10]

Triumphal accounts in this era of growth, cultural absorption and political instability find the erosion of "Roman virtue" in the fruits of conquest. Livy gives due attention to the plundered wealth of statuary, gold and silver, but particular weight to the specialist chefs, flute girls, one-legged tables and other "dinner-party amusements" brought to Rome from exotic Galatia for the (putative) triumph of Gnaeus Manlius Vulso in 187 BCE.[11] Livy's account of the spoils is thorough, not only in his descriptions of its pernicious "foreign luxuries" but its captives, wagonloads of booty and the celebratory songs of the soldiery. Yet Florus has the senate turn down Vulso's application — no triumph takes place.[12] Livy also has Scipio Africanus make a self-deprecatory request for victories in Spain in 206 BCE — without much expectation, because although he had been an aedilis curulis, his command rights in Spain had been granted by a special vote of the people. There was as yet no precedent for a triumph except in a senior magistracy with command rights (praetura or consulate) or with command rights extended from such a magistacy (viri pro praetore and pro consule): on these grounds, according to Livy, the request was quite properly refused. No triumph was held.[13] Yet Polybius describes its splendours — and reactions to them — in some detail.[14] Neither of these writers was contemporary to the event. Each seems to infer what ought to have happened; each extols humility and service, and remarks the perils of vaunting personal pride and ambition. These preoccupations frustrate attempts to reconstruct a "typical" triumph from most written accounts: where details are given, they are invariably remarkable, exceptional, strange or superlative. The "obvious" ritual details tend to be sketchy, interpretive or entirely absent.[15]

Towards the end of the Republic, Cicero noted how self-aggrandisement could be extended to dynastic ancestors, and further distort an already fragmentary and unreliable historical tradition.[16][17][18]

The Fasti Triumphales

The Fasti Triumphales (also called Acta Triumphalia) are fragmentary, inscribed stone tablets which were erected somewhere in the Forum Romanum during the reign of the first emperor, Augustus, and date from approximately 12 BCE. They record over 200 triumphs, starting with three mythical triumphs of Romulus in 753 BCE, and ending with that of Lucius Cornelius Balbus in 19 BCE.[19]

They were part of the Augustan fasti Capitolini. The standard modern edition is that of Attilio Degrassi, in Inscriptiones Italiae, vol.XIII, fasc.1 (Rome, 1947).

Intact entries give the formal name, including filiation (forenames of father and grandfather) of the vir triumphalis, the name of the people(s) or command province whence the triumph was awarded, and the date of the actual ceremonial procession into the urbs. Fragments of similar date and style from Rome and provincial Italy appear to be modeled on the Augustan Fasti, and fill some of its gaps.[20]Legal requirements

In the Republic, the triumph was the highest honour. In order to receive a triumph, the Leader must:

- Win a significant victory over a foreign enemy, killing at least 5,000 enemy troops, and earn the title imperator.

- Be an elected magistrate with the power of imperium, i.e. a dictator, consul, or a praetor.

- Bring the army home, signifying that the war was over and that the army was no longer needed. This only applied with a citizen army. By the imperial period the proper triumph was reserved for the emperor and his family. If a general was awarded a triumph by the emperor, he would march with a token number of his troops.

- In the Republican period, the senate had to give approval for a triumph based on the above mentioned requirements.

Internal conflicts (civil wars) did not, at least in theory, merit triumphs. The defeated enemy had to be of equal status, so defeating a slave revolt could therefore not earn a triumph.

Processional order and rites

In the absence of complete or clear records of any triumphal ceremony, attempted reconstruction presumes a traditional, conservative framework in which details omitted from one account can be furnished from another. A reconstruction follows, based on Ramsey, 1875.[21]

The ceremony began outside the Servian Walls in the Campus Martius, on the western bank of the Tiber. The vir triumphalis entered the city in his chariot through the Porta Triumphalis, which was only opened for these occasions. As he entered the city (as defined by the pomerium, he was met by the senate and magistrates and legally surrendered his command. The parade then proceeded along the Via Triumphalis (the modern Via dei Fori Imperiali) to the Circus Flaminius then the Circus Maximus. A captured enemy ruler or general might be paraded then taken to the Tullianum for execution: Jugurtha was starved to death there, and Vercingetorix was strangled. Some defeated leaders, such as Zenobia of Palmyra, were spared. The procession continued along the Via Sacra to the Forum and ascended the Capitoline Hill to the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, the final destination. The route would be lined with cheering crowds who would shower the triumphator with flowers.

At the Capitoline Hill the vir triumphalis sacrificed white bulls to Jupiter. He then entered the temple to offer his wreath to the god as a sign that he had no intentions of becoming the king of Rome. Once this part of the ceremony was over, temples were kept open and incense burned at the altars. The soldiers would disperse to the city to celebrate. Often a banquet was served for the citizens in the evening.

To better celebrate the triumph, a monument was sometimes erected. This is the origin of the Arch of Titus and the Arch of Constantine, not far from the Colosseum, or perhaps near a battle site as is the case for the Tropaeum Traiani. The monumental Meta Sudans was erected by the Flavians to mark the point where the triumph route turned from the Via Triumphalis into the Via Sacra and the Forum.[citation needed]

It is difficult to determine what is a "real" Roman triumph in the late period. Therefore it is also impossible to say who was the last triumphator. The candidates include Emperor Honorius (403) and Flavius Belisarius (ostensibly "sitting in" for Emperor Justinian I), in recognition for his victory over the Vandals. It was held in Constantinople in 534.[citation needed]

During the approximately 1900 years of the history from the beginnings of the Roman Republic to the final disappearance of the Eastern Roman Empire about 500 triumphs were celebrated.[citation needed]

- The Senate, headed by the magistrates without their lictors.

- Trumpeters

- Carts with the spoils of war

- White bulls for sacrifice

- The arms and insignia of the conquered enemy

- The enemy leaders themselves, with their relatives and other captives

- The lictors of the imperator, their fasces wreathed with laurel

- The imperator himself, in a chariot drawn by two (later four) horses

- The adult sons and officers of the imperator

- The army without weapons or armor (since the procession would take them inside the pomerium), but clad in togas and wearing wreaths. During the later periods, only a selected company of soldiers would follow the commander in the triumph, as a singular honour.[citation needed]

The imperator may possibly have had his face painted red and wore a corona triumphalis, a tunica palmata and a toga picta. He may have been accompanied in his chariot by a slave holding a golden wreath above his head and constantly reminding the commander of his mortality by whispering into his ear. However, this is based on slender and disputed evidence.[citation needed]

The words that the slave is said to have used are not known, but suggestions include "Respice te, hominem te memento" ("Look behind you, remember you are only a man") and "Memento mori" ("Remember (that you are) mortal").[22]

Exotic animals, musicians and slaves carrying pictures of conquered cities and signs with names of conquered peoples are found in accounts by[citation needed].

Suetonius claims that the emperor Vespasian regretted his own triumph, because its vast length and slow movement bored him.[23]

Some significant Triumphs

The Ovation and Alban Mount Triumph of M. Marcellus, 211 BCE.

Livy XXVI 21:

At the end of that same summer when M. Marcellus had come to the City from Sicily province the Senate was given for him at the temple of Bellona by the praetor C. Calpurnius. (2) There, once he had described his achievements, he complained mildly about his soldiers' lot more than his own regarding the fact that after the settlement of the province he had not been permitted to bring his army home. He also asked that he be permitted to enter the City in triumph. He did not obtain his request. (3) After a lengthy debate whether it was less appropriate to refuse a triumph to man, in his presence, in whose name when absent a thanksgiving (supplicatio) had been decreed and honour paid to the Immortal Gods by reason of the things successfully accomplished under his leadership, (4) or for a man to triumph as though a war had been concluded whom they had ordered to hand over his army to a successor (something that would not be decreed if no war remained in the province) when his army, the witness of a deserved as of an undeserved triumph, was far away, the middle course seemed best: that he should enter the City in ovation (ovans). (5) The tribunes of plebs proposed to the People on the authority of the Senate that there should be command rights (imperium) for M. Marcellus on the day he should enter the City in ovation. (6) On the day before he was due to enter the City he triumphed on the Alban Mount. Then in ovation he brought much booty before him into the City. (7) Together with a painting of the capture of Syracuse, catapults, ballistae and all the other engines of war were carried along, as well as the ornaments of a peace of long duration and of royal opulence, (8) plate of skilfully wrought silver and bronze, other household furniture, precious garments and many renowned statues by which Syracuse had been distinguished among the foremost cities of Greece. (9) In addition eight elephants were led by to symbolize his Punic victory and not the least spectacle were Sosis of Syracuse and the Spaniard Moericus proceeding in front with golden wreaths. (10) Of these the one had been the nocturnal guide of the entry into Syracuse while the other had betrayed the Island and the garrison there. (11) Citizenship was granted to them both and it was ordered that five hundred iugera of land be granted to each of them too: for Sosis in the Land of Syracuse which had belonged either to the king or enemies of the Roman People, plus such a house in Syracuse that he desired belonging to anyone who had been punished according to the laws of war, (12): for Moericus and the Spaniards who had gone over with him, a city and land in Sicily belonging to those who had defected from the Roman People. (13) M. Cornelius was commissioned to assign to them the city and land wherever seemed right to him. Four hundred iugera of land in that same territory were decreed to Belligenes, by whom Moericus had been enticed to swap sides.

Cf. Plutarch Marcellus 19-22.

Note that the rewards accorded to Sosis and Moericus made them not just Roman citizens but wealthy ones in the prima classis, and hence potential candidates for office in Rome.

Later in the year the Sicilian commander, M. Cornelius Cethegus, awarded the city of Morgantina and its lands to Moericus and his Spaniard mercenaries. The destruction which ensued during the expulsion of the Greek population has been excavated by modern archaeologists and the finds are central to the great controversy of the introduction of the Roman denarius silver coinage.[24]The three triumphs of Pompeius Magnus

The three triumphs awarded Pompeius Magnus ("Pompey the Great") were thoroughly documented, not least because they were controversial to their contemporaries and to later writers. His first, in 80 or 81 BCE, was technically illegal, reluctantly granted by a cowed and divided Senate when Pompey was aged only 24, a mere equestrian.[25] Roman conservatives disapproved.[26] For others, his youthful success was the mark of a prodigious military talent, divine favour and personal brio that merited popular support. However, the triumphal day did not go quite to plan. To represent his African conquest, and perhaps to outdo even Bacchus, Pompey had a team of elephants yoked to his triumphal chariot, but they proved too tight a fit for one of the gates en route to the Capitol. Pompey had to dismount and wait while a horse team was yoked in their place.[27] This embarrassment would have delighted his critics, and probably some of his soldiers — whose demands for cash had been near-mutinous.[28] Even so, his firm stand on the matter of cash raised his standing among the conservatives, and Pompey seems to have learned a lesson in populist politics.

For his second triumph, his donatives were said to break all records, though the amounts in Plutarch's account are implausibly high: Pompey’s lowest ranking soldiers each received 6000 sesterces (about six times their annual pay) and his officers around 5 million sesterces each.[29]

Panel from a representation of a triumph of Marcus Aurelius. Note the winged genius at the head of the emperor, denoting his divinity.

Panel from a representation of a triumph of Marcus Aurelius. Note the winged genius at the head of the emperor, denoting his divinity.

His third triumph, held in 61 BCE to celebrate his victory over Mithradates, was an opportunity to outdo even himself - and certainly his rivals. Triumphs traditionally lasted for one day. Pompey’s went on for two days of unprecedented novelty, wealth and luxury.[30] Plutarch claimed that this triumph represented Pompey's - and therefore Rome's - domination over the entire world, an achievement to outshine even Alexander's.[31][32] Pliny's narrative dwells upon a gigantic portrait-bust of Pompey, a thing of “eastern splendor” entirely covered with pearls, and with the benefit of hindsight, has this disembodied head anticipate Pompey’s later defeat at Pharsalus and subsequent decapitation in Egypt.[33] In 55 BCE, Pompey's "gift to the Roman People" of a gigantic, architecturally daring theatre was dedicated to Venus Victrix, and thereby connected the once equestrian vir triumphalis to Aeneas, son of Venus and ancestor of Rome itself. For its inauguration, the portico was filled with the spoils of his wars, including statuary, paintings and the personal wealth of foreign kings. Beard interprets this as a commemoration and extension of triumphal fame.[34]

Triumph as Imperial privilege

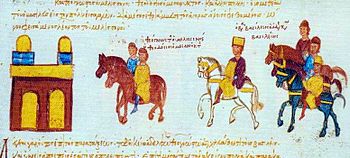

Miniature representation of the emperor Basil II's triumph through the Forum of Constantinople, from the (Madrid Skylitzes)

Miniature representation of the emperor Basil II's triumph through the Forum of Constantinople, from the (Madrid Skylitzes)

The triumphal destination was the temple of Jupiter Capitolinis (Capitoline Jupiter), to whom the victor offered his laurel crown and two perfect white bulls as a thanks-offering. The distinctive "kingly" (or possibly, godly) costume and appearance of the vir triumphalis had been traditionally reserved for his temporary elevation on his day of triumph.[35]

In the few years that led up to the Principate, these restrictions were eroded. Julius Caesar was granted the right to wear the laurel wreath and “some elements” of triumphal dress at all festivals - Cassius Dio adds that Caesar wore the laurel wreath “wherever and whenever”, excusing this as a cover to his baldness.[36]

Following Caesar's murder, Octavian assumed permanent title of imperator and inaugurated his well prepared principate under the name Augustus in 27 BCE. Only the year before he had blocked the senatorial award of a triumph to Marcus Licinius Crassus, despite the latter's acclamation in the field as Imperator and his eminent merit by all traditional criteria - barring only full consulship. Augustus claimed the victory as his own but permitted Crassus a second, listed on the Fasti for 27 BCE, by which time Augustus was abolishing various proconsulates to form his own Imperial provinces.[37] Crassus was also denied the rare (and in his case, technically permissible) honour of dedicating the spolia opima of this campaign to Jupiter Feretrius.[38] Inscriptions on the Fasti Triumphales come to a seemingly abrupt full-stop in 19 BCE, by which time the triumph had been absorbed into the Augustan Imperial cult system in which only the emperor - the supreme Imperator (or very occasionally, a close relative who had glorified the Imperial gens) - would be accorded such a supreme honour. Those outside the Imperial family, like Aulus Plautius under Claudius, might be granted a "lesser triumph", or ovation.[39]

Thereafter the number and frequency of triumphs fell dramatically. Only 5 are known up to 71 CE, none between the triumph of Claudius over Britain (44 CE) and Trajan's posthumous triumph of 117-8 CE, and none from then until the triumph of Marcus Aurelius over Parthia in 166 CE. For this period as for all others, historical sources presume a shared experience with their readership, despite the increasing rarity of Triumphal ceremony. Instead of ceremonial detail they offer statistics (which may or may not be wildly inflated) and lessons in virtue. There is little reason to prefer one version to another - few, if any, are primary sources. Most were compiled long after the triumph had been fully co-opted into a Imperial-monarchic system of government which to an earlier Republican would have seemed very un-Roman indeed.[40]

Legacy

Standardized reconstructions are largely inventive, but offer an orderly and serviceable set of instructions. These were used to organize processions which sought ennobling connections with the classical past, particularly during the Renaissance when the fragmentary Fasti were unearthed and partially restored. In 1550, the triumphant entry into Rouen of Henri II of France was compared to Pompey's third triumph of 61 BCE at Rome: "No less pleasing and delectable than the third triumph of Pompey... magnificent in riches and abounding in the spoils of foreign nations".[41] A triumphal arch made for the entry into Paris of Louis XIII in 1628 carried a depiction of Pompey.[42]

Listing of the Roman viri triumphales to 19 BCE

See the Attalus.org, Fasti Triumphales

See also

- Imperial fora

- Joyous Entry

- Ovation

- Triumphal arch

- Triumphal honours

- Victory parade

Notes

- ^ Beard, 72-5. See also Diodorus, 4.5 at Thayer: Uchicago.edu

- ^ Beard et al, 85-7: see also Polybius, 10.2.20, who suggests that Scipio's assumption of divine connections (and the personal favour of divine guidance) was unprecedented and suspiciously "Greek" to his more conservative peers.

- ^ See also Galinsky, 106, 126-49, for Heraklean/Herculean associations with Alexander, and with Scipio and later triumphing Roman generals.

- ^ Beard et al, vol. 1, 44-5, 59-60: see also Plutarch, Romulus (trans. Dryden) at The Internet Classics Archive MIT.edu

- ^ Bowersock, 1994, 157.

- ^ Ovid, The Erotic Poems, 1.2.19-52. Trans P. Green.

- ^ Pliny attributes the invention of the triumph to "Father Liber" (identified with Dionysus): see Pliny, Historia Naturalis, 7.57 (ed. Bostock) at Perseus: Tufts.edu

- ^ Bosworth, 67-79, notes that Arrian's attributions here are non-historic and their details almost certainly apocryphal: see Arrian, 6, 28, 1-2.

- ^ Beard, 67: citing Valerius Maximus, 4.4.5., and Apuleius, Apol.17

- ^ Dionysus of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, 2.34.3.

- ^ Livy, 39.6-7: cf Pliny, Historia Naturalis, 34.14.

- ^ Livy, 39, 6–7. Florus, Epitome Rerum Romanarum, 1, 27.

- ^ Livy, 28, 38, 4–5.

- ^ Polybius, 11.33.7.

- ^ Beard, 4.

- ^ Cicero, Brutus, 63.

- ^ See also Livy, 8, 40.

- ^ Beard, 79, notes at least one ancient case of what seems blatant fabrication, in which two triumphs became three.

- ^ Romulus' three triumphs are confirmed by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Antiquitates Romanae, 2.54.2 & 2.55.5) who may have seen the Fasti: but Livy (1.10.5-7) allows Romulus the spolia opima, not a "triumph". Neither author mentions the two triumphs attributed by the Fasti to the last king of Rome, Tarquin. See Beard, 74 & endnotes 1 &2.

- ^ Beard, 61-2, 66-7.

- ^ Ramsay, W. Triumphus pp1163-67 in Smith, W. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875: from Bill Thayer's website: Uchicago.edu, Triumphus

- ^ Tertullian, Apologeticus, Chapter 33,4.

- ^ Suetonius, Vespasian, 12

- ^ See e. g. William T. Loomis "The Introduction of the Denarius", 338-355 in R. W. Wallace & E. M. Harris (eds.) Transitions to Empire. Essays in Greco-Roman History, 360-146 B.C., in honor of E. Badian (University of Oklahoma Press, 1996)

- ^ Beard, 16: he was aged 25 or 26 in some accounts.

- ^ Dio Cassius, 42.18.3.

- ^ Pliny, Historia Naturalis, 8.4: Plutarch, Pompey, 14.4.

- ^ Beard, 16, 17.

- ^ Beard, 39-40, notes that the introduction of such vast sums into the Roman economy would have left substantial traces, but none are evidenced: citing Brunt, (1971) 459-60; Scheidel, (1996); Duncan-Jones, (1990), 43, & (1994), 253.

- ^ Beard, 9, cites Appian's very doubtful "75,100,000" drachmae carried in the procession as 1.5 times his own estimate of Rome's total annual tax revenue: Appian, Mithradates, 116.

- ^ Beard, 15-16: citing Plutarch, Pompey, 45, 5.

- ^ Beard, 16. For further elaboration on Pompey's 3rd triumph, see also Plutarch, Sertorius, 18, 2, at Thayer Uchicago.edu: Cicero, Man. 61: Pliny, Nat. 7, 95.

- ^ Beard, 35: Pliny, Historia Naturalis, 37, 14-16.

- ^ Beard, 22-3.

- ^ Beard, 272-5.

- ^ Beard, 275.

- ^ Syme, 272-5: Google Books Search

- ^ Southern, 104: Google Books Search

- ^ Suetonius, Lives, Claudius, 24.3: given for the conquest of Britain. Claudius was "granted" a triumph by the Senate. According to Suetonius, he gave "triumphal regalia" to his prospective son-in-law, who was still "only a boy". Thayer: Uchicago.edu

- ^ Beard, 61-71.

- ^ Beard, 31. See 32, Fig. 7 for a contemporary depiction of Henri's "Romanised" procession.

- ^ Beard, 343, footnote 65.

References

- Beard, Mary: The Roman Triumph,The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, England, 2007. (hardcover). ISBN 9780674026131

- Beard, M., Price, S., North, J., Religions of Rome: Volume 1, a History, illustrated, Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0521316820

- Bosworth, A. B., From Arrian to Alexander: Studies in Historical Interpretation, illustrated, reprint, Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0198148631

- Bowersock, Glen W., "Dionysus as an Epic Hero," Studies in the Dionysiaca of Nonnos, ed. N. Hopkinson, Cambridge Philosophical Society, suppl. Vol. 17, 1994, 156-66.

- Brennan, T. Corey: "Triumphus in Monte Albano", 315-337 in R. W. Wallace & E. M. Harris (eds.) Transitions to Empire. Essays in Greco-Roman History, 360-146 B.C., in honor of E. Badian (University of Oklahoma Press, 1996) ISBN 0806128631

- Galinsky, G. Karl, The Herakles theme: the adaptations of the hero in literature from Homer to the twentieth century, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, 1972. ISBN 0631140204

- Goell, H. A., De triumphi Romani origine, permissu, apparatu, via (Schleiz, 1854)

- Künzl, E., Der römische Triumph (Münich, 1988)

- Lemosse, M., "Les éléments techniques de l'ancien triomphe romain et le probleme de son origine", in H. Temporini (ed.) ANRW I.2 (de Gruyter, 1972). Includes a comprehensive bibliography.

- MacCormack, Sabine, Change and Continuity in Late Antiquity: the ceremony of "Adventus", Historia, 21, 4, 1972, pp 721–52.

- Pais, E., Fasti Triumphales Populi Romani (Rome, 1920)

- Richardson, J. S., "The Triumph, the Praetors and the Senate in the early Second Century B.C.", JRS 65 (1975), 50-63

- Southern, Pat, Augustus, illustrated, reprint, Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0415166314

- Syme, Ronald, The Augustan Aristocracy (Oxford University Press, 1986; Clarendon reprint with corrections, 1989) ISBN 0198147317

- Versnel, H S: Triumphus: An Inquiry into the Origin, Development and Meaning of the Roman Triumph (Leiden, 1970)

External links

- William Fitzgerald, December 5, 2007 TLS review of Beard, The Roman Triumph, 2007. Timesonline.co.uk, "Roman defeat in victory"

- Fasti Triumphales at attalus.org. Partial, annotated English translation. From A. Degrassi's "Fasti Capitolini", 1954. Attalus.org

Categories:- Military awards and decorations of ancient Rome

- Ancient Roman religion

- Victory

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.