- Haleakalā

-

Not to be confused with Haleʻākala.

Haleakalā East Maui Volcano

HaleakalāElevation 10,023 ft (3,055 m) Prominence 10,023 ft (3,055 m)

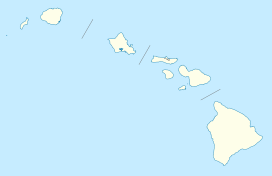

HP of MauiListing Ultra Location Maui, Hawaii, USA Range Hawaiian Islands Coordinates 20°42′35″N 156°15′12″W / 20.70972°N 156.25333°WCoordinates: 20°42′35″N 156°15′12″W / 20.70972°N 156.25333°W Topo map USGS Kilohana (HI) Geology Type Shield volcano Age of rock <1.0 Ma Volcanic arc/belt Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain Last eruption ~18th Century Climbing Easiest route paved highway Haleakalā (

/ˌhɑːliːˌɑːkəˈlɑː/; Hawaiian: [ˈhɐleˈjɐkəˈlaː]), or the East Maui Volcano, is a massive shield volcano that forms more than 75% of the Hawaiian Island of Maui. The western 25% of the island is formed by the West Maui Mountains.

/ˌhɑːliːˌɑːkəˈlɑː/; Hawaiian: [ˈhɐleˈjɐkəˈlaː]), or the East Maui Volcano, is a massive shield volcano that forms more than 75% of the Hawaiian Island of Maui. The western 25% of the island is formed by the West Maui Mountains.Contents

History

Early Hawaiians applied the name Haleakalā ("house of the sun") to the general mountain. Haleakalā is also the name of a peak on the south western edge of Kaupō Gap. In Hawaiian folklore, the depression at the summit of Haleakalā was home to the grandmother of the demigod Māui. According to the legend, Māui's grandmother helped him capture the sun and force it to slow its journey across the sky in order to lengthen the day.

The tallest peak of Haleakalā, at 10,023 feet (3,055 m), is Puʻu ʻUlaʻula (Red Hill). From the summit one looks down into a massive depression some 11.25 km (7 mi) across, 3.2 km (2 mi) wide, and nearly 800 m (2,600 ft) deep. The surrounding walls are steep and the interior mostly barren-looking with a scattering of volcanic cones.

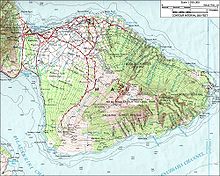

According to the United States Geological Survey USGS Volcano Warning Scheme for the United States the Volcanic-Alert Level as of June 2011 was "normal".[1] A Normal status is used to designate typical volcanic activity in a non-eruptive phase. Haleakala has produced numerous eruptions in the last 30,000 years, including in the last 500 years. This volcanic activity has been along two rift zones, the southwest and east. These two rift zones together form an arc that extends from La Perouse Bay on the southwest, through the Haleakalā Crater and to Hāna, to the east. The east rift zone continues under the ocean beyond the east coast of Maui as Haleakalā Ridge, making the combined rift zones one of the longest in the Hawaiian Islands chain.

Until recently, East Maui Volcano was thought to have last erupted around 1790, based largely on comparisons of maps made during the voyages of La Perouse and George Vancouver. Recent advanced dating tests, however, have shown that the last eruption was more likely to have been in the 17th century.[2] These last flows from the southwest rift zone of Haleakalā make up the large lava deposits of the Ahihi Kina`u/La Perouse Bay area of South Maui. In addition, contrary to popular belief, Haleakalā "crater" is not volcanic in origin, nor can it accurately be called a caldera (which is formed through when the summit of a volcano collapses to form a depression). Rather, scientists believe that Haleakalā's "crater" was formed when the headwalls of two large erosional valleys merged at the summit of the volcano. These valleys formed the two large gaps — Koʻolau on the north side and Kaupō on the south — on either side of the depression.

Macdonald, Abbott, & Peterson[3] state it this way:

- Haleakalā is far smaller than many volcanic craters (calderas); there is an excellent chance that it is not extinct, but only dormant; and strictly speaking it is not of volcanic origin, beyond the fact that it exists in a volcanic mountain.

Lava Flow Hazard Zones

Unlike Hawaii Island, where the USGS mapped the island into 1 of 9 Lava Flow Hazard Zones, there appears to have been little attempt to differentiate risks for different areas of Maui. However, it would follow based upon the pattern set on Hawaii Island that areas of greatest risk would be at the summit and along the rift zones. Areas of second greatest risk would be immediately downhill from summit and rift zones. Areas of third greatest risk would be protected by some current geological feature such as a hill or valley.

National Park

This rare species of Silversword is fragile and lives only upon the slopes of Haleakalā.

This rare species of Silversword is fragile and lives only upon the slopes of Haleakalā.

Surrounding and including the crater is Haleakalā National Park, a 30,183-acre (122.15 km2) park, of which 24,719 acres (100.03 km2) are wilderness.[4] The park includes the summit depression, Kipahulu Valley on the southeast, and ʻOheʻo Gulch (and pools), extending to the shoreline in the Kipahulu area. From the summit, there are two main trails leading into Haleakalā: Sliding Sands Trail and Halemauʻu Trail.

The temperature near the summit tends to vary between about 40°F (5°C) and 60°F (16°C) and, especially given the thin air and the possibility of dehydration at that elevation, the walking trails can be more challenging than one might expect. Despite this, Haleakalā is popular with tourists and locals alike, who often venture to its summit, or to the visitor center just below the summit, to view the sunrise. There is no lodging, food, or gas available in the park.[5]

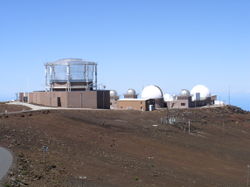

Astrophysical research

Because of the remarkable clarity, dryness, and stillness of the air, and its elevation (with atmospheric pressure of 71 kPa/533 mm Hg[6]), as well as the absence of the lights of major cities, the summit of Haleakalā (like Mauna Kea) is one of the most sought-after locations in the world for ground-based telescopes. As a result of the geographic importance of this observational platform, experts come from all over the world to take part in research at "Science City", an astrophysical complex operated by the U.S. Department of Defense, University of Hawaii, Smithsonian Institution, Air Force, Federal Aviation Agency, and others.

Some of the telescopes operated by the US Department of Defense are involved in researching man-made (e.g. spacecraft, monitoring satellites, rockets, and laser technology) rather than celestial objects. The program is in collaboration with defense contractors in the Maui Research and Technology Park in Kihei. The astronomers on Haleakalā are concerned about increasing light pollution as Maui's population grows. Nevertheless, new telescopes are added, such as the Pan-STARRS in 2006.[7][8]

Transportation

A well traveled Haleakalā Highway, completed in 1935, is road mainly composed of switchbacks that leads to the peak of Haleakala.[9] The road is open to the public (although parts of it are restricted) and is a well-maintained two-lane highway containing many blind turns and very steep dropoffs. Local animals, including cattle, are often encountered in the roadway. The park charges a vehicle entrance fee of USD$10. Public transportation does not go through the park, but tour buses visit the summit regularly. Cycling and horseback riding are other popular ways to explore the park. The Island does have a unique tour via bike. There are a few organizations on Maui, which will pick people up at their hotels, take them to the top of Haleakalā and outfit them with a bicycle to glide down the road from just outside the National Park boundary (starting at 6500 ft altitude). Tour operators used to run bike rides down the entire 27 miles from the summit, but in 2007 the National Park Service suspended all commercial bicycle activity within the park boundaries, following multiple fatal accidents.[10]

See also

- Evolution of Hawaiian volcanoes

- Mountain peaks of North America

- Mountain peaks of the United States

- Hawaii hotspot

- Haleakalā Wilderness

Notes

- ^ Current Alerts for U.S. Volcanoes

- ^ "Youngest lava flows on East Maui probably older than A.D. 1790". United States Geological Survey. September 9, 1999. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/1999/99_09_09.html. Retrieved 1999-10-04.

- ^ Macdonald, Abbott, & Peterson p. 391

- ^ "Park Management". Haleakalā National Park. National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/hale/parkmgmt/. Retrieved 2010-10-26.

- ^ Decker, Robert; Decker, Barbara (2001). Volcanoes In America's National Parks. New York: WW Norton & Company Inc.. p. 133. ISBN 9622176771.

- ^ "Altitude Calculator". http://www.altitude.org/air_pressure.php.

- ^ "Watching and waiting". The Economist. 2008-12-04. http://www.economist.com/science/displaystory.cfm?story_id=12719347. Retrieved 2008-12-06. From the print edition

- ^ Robert Lemos (2008-11-24). "Giant Camera Tracks Asteroids". Technology Review (MIT). http://www.technologyreview.com/computing/21705/page1/. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ^ Haleakala Highway: - The Journal of Pacific History

- ^ Haleakala bike tours suspended - Yahoo! News/Associated Press

References

- Haleakalā National Park Official Website, accessed March 2010.

- Macdonald, Gordon A., Agatin T. Abbott, and Frank L. Peterson. 1983. Volcanoes in the Sea. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu. 517 pp.

External links

Categories:- Landforms of Maui

- Mountains of Hawaii

- Volcanoes of Maui Nui

- Hotspot volcanoes

- Shield volcanoes

- Potentially active volcanoes

- United States National Park high points

- Haleakalā National Park

- Pleistocene volcanoes

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.