- Recapitulation theory

-

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelism—and often expressed as "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—is a disproven hypothesis that in developing from embryo to adult, animals go through stages resembling or representing successive stages in the evolution of their remote ancestors. With different formulations, such ideas have been applied to several fields, including biology, anthropology[1], education theory[2] and developmental psychology.[3] While some examples of embryonic stages showing superficial features of ancestral organisms exist, the ontological hypothesis itself has been completely disproven[4][5].

Contents

Origins

The general agreement among historians is that the concept originated in the 1790s among the German Natural philosophers.[6] The first formal formulation was proposed by Étienne Serres in 1824–26 as what became known as the "Meckel-Serres Law", it attempted to provide a link between comparative embryology and a "pattern of unification" in the organic world. It was supported by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and became a prominent part of his ideas which suggested that past transformations of life could have had environmental causes working on the embryo, rather than on the adult as in Lamarckism. These naturalistic ideas led to disagreements with Georges Cuvier. It was widely supported in the Edinburgh and London schools of higher anatomy around 1830, notably by Robert Edmond Grant, but was opposed by Karl Ernst von Baer's ideas of divergence, and attacked by Richard Owen in the 1830s.[7]

Haeckel

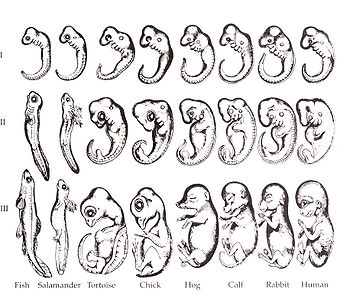

Romanes's 1892 copy of Ernst Haeckel's controversial embryo drawings (this version of the figure is often attributed incorrectly to Haeckel).[8]

Romanes's 1892 copy of Ernst Haeckel's controversial embryo drawings (this version of the figure is often attributed incorrectly to Haeckel).[8]

Ernst Haeckel attempted to synthesize the ideas of Lamarckism and Goethe's Naturphilosophie with Charles Darwin's concepts. While often seen as rejecting Darwin's theory of branching evolution for a more linear Lamarckian "biogenic law" of progressive evolution, this is not accurate: Haeckel used the Lamarckian picture to describe the ontogenic and phylogenic history of the individual species, but agreed with Darwin about the branching nature of all species from one, or a few, original ancestors.[9] Since around the start of the twentieth century, Haeckel's "biogenetic law" has been refuted on many fronts.[10]

Haeckel formulated his theory as "Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny". The notion later became simply known as the recapitulation (OED: 'a summing up or brief repetition') theory. Ontogeny is the growth (size change) and development (shape change) of an individual organism; phylogeny is the evolutionary history of a species. Haeckel's recapitulation theory claims that the development of advanced species passes through stages represented by adult organisms of more primitive species.[10] Otherwise put, each successive stage in the development of an individual represents one of the adult forms that appeared in its evolutionary history.

For example, Haeckel proposed that the pharyngeal slits of the pharyngeal arches in the neck of the human embryo resembled gill slits of fish, thus representing an adult "fishlike" developmental stage as well as signifying a fishlike ancestor. Embryonic pharyngeal slits, formed when the thin branchial plates separating pharyngeal pouches and ectodermal grooves perforate, open the pharynx to the outside. Pharyngeal pouches appear in all tetrapod animal embryos: in mammals, the first pharyngeal pouch develops into the lower jaw (Meckel's cartilage), the malleus and the stapes. At a later stage, all pharyngeal slits close, only the ear remaining open.[11] But these embryonic pharyngeal arches, pouches, and slits could not at any stage carry out the same function as the gills of an adult fish.

Haeckel produced several embryo drawings that often overemphasized similarities between embryos of related species. The misinformation was propagated through many biology textbooks, and popular knowledge, even today. Modern biology rejects the literal and universal form of Haeckel's theory.[12]

Haeckel's drawings were disputed by Wilhelm His, who had developed a rival theory of embryology.[13] His developed a "casual-mechanical theory" of human embryonic development.[14]

Darwin's view, that early embryonic stages are similar to the same embryonic stage of related species but not to the adult stages of these species, has been confirmed by modern evolutionary developmental biology.

Historical influence

Although Haeckel's specific form of recapitulation theory is now discredited among biologists, it had a strong influence on social and educational theories of the late 19th century.

English philosopher Herbert Spencer was one of the most energetic promoters of evolutionary ideas to explain many phenomena. He compactly expressed the basis for a cultural recapitulation theory of education in the following claim, published in 1861, five years before Haeckel first published on the subject:[2]

If there be an order in which the human race has mastered its various kinds of knowledge, there will arise in every child an aptitude to acquire these kinds of knowledge in the same order.... Education is a repetition of civilization in little.[15]

— Herbert Spencer

The maturationist theory of G. Stanley Hall was based on the premise that growing children would recapitulate evolutionary stages of development as they grew up and that there was a one-to-one correspondence between childhood stages and evolutionary history, and that it was counterproductive to push a child ahead of its development stage. The whole notion fit nicely with other social Darwinist concepts, such as the idea that "primitive" societies needed guidance by more advanced societies, i.e. Europe and North America, which were considered by social Darwinists as the pinnacle of evolution.[citation needed]

In Philosophy and Art Criticism

The Austrian pioneer in psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, also held a favorable position towards Haeckel's doctrine. He was trained as a biologist under the influence of recapitulation theory at the time of its domination, and retained a Lamarckian outlook with justification from the recapitulation theory.[16] He also distinguished between physical and mental recapitulation, in which the differences would become an essential argument for his theory of neuroses.[16]

More recently, several art historians, most prominently musicologist Richard Taruskin,[17]have applied the term "ontogeny becomes phylogeny" to the process of creating and recasting art history, often to assert a perspective or argument. For example, the peculiar development of the works by modernist composer Arnold Schoenberg (here an "ontogeny") is generalized in many histories into a "phylogeny" – a historical development ("evolution") of Western Music toward atonal styles of which Schoenberg is a representative. Such historiographies of the "collapse of traditional tonality" are faulted by art historians as asserting a rhetorical rather than historical point about tonality's "collapse".

Taruskin also developed a variation of the motto into the pun "ontogeny recapitulates ontology" to refute the concept of "absolute music" advancing the socio-artistic theories of Carl Dalhaus. Ontology is the investigation of what exactly something is, and Taruskin asserts that an art object becomes that which society and succeeding generations made of it. For example, composer Johann Sebastian Bach's St. John Passion, composed in the 1720's, was appropriated by the Nazi regime in the 1930's for propaganda. Taruskin claims the historical development of the Passion (its ontogeny) as a work with an anti-Semitic message does, in fact, inform the work's identity (its ontology), even though that was an unlikely concern of the composer. Music or even an abstract visual artwork can not be truly autonomous ("absolute") because it is defined by its historical and social reception.

Modern observations

Generally, if a structure pre-dates another structure in evolutionary terms, then it also appears earlier than the other in the embryo. Species which have an evolutionary relationship typically share the early stages of embryonal development and differ in later stages. Examples include:

- The backbone, the common structure among all vertebrates such as fish, reptiles and mammals, appears as one of the earliest structures laid out in all vertebrate embryos.

- The cerebrum in humans, the most sophisticated part of the brain, develops last.

If a structure vanished in an evolutionary sequence, then one can often observe a corresponding structure appearing at one stage during embryonic development, only to disappear or become modified in a later stage. Examples include:

- Whales, which have evolved from land mammals, don't have legs, but tiny remnant leg bones lie buried deep in their bodies. During embryonal development, leg extremities first occur, then recede. Similarly, whale embryos have hair at one stage (like all mammalian embryos), but lose most of it later.

- The common ancestor of humans and monkeys had a tail, and human embryos also have a tail at one point; it later recedes to form the coccyx.

- The swim bladder in fish presumably evolved from a sac connected to the gut, allowing the fish to gulp air. In most modern fish, this connection to the gut has disappeared. In the embryonal development of these fish, the swim bladder originates as an outpocketing of the gut, and is later disconnected from the gut.

- In bird embryos, very briefly fingers start to develop. After a short time, they partly disappear again, partly are fused with the handbones to form the carpometacarpus.

But this rule-of-thumb is not universal. Modern birds, for example, though descended from toothed animals, never grow teeth even as embryos. However, they still possess the genes required to do so, and tooth formation has been experimentally induced in chickens.

Neil Shubin notes that there is an important difference between recapitulation theory and the ideas of Karl Ernst von Baer. Baer's work, while also drawing comparisons between species, and paying attention to the parallels between embryonic development and the evolution of species, focused on a comparison between embryos of different species to one another, rather than a comparison between embryos of one species and the adult forms of that species' ancestor species.[18]

References

- ^ Carneiro, (1981) Robert L. Herbert Spencer as an Anthropologist Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol. 5, 1981, pp.156-60

- ^ a b Kieran Egan, The Educated Mind: How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding., p.27 (University of Chicago Press, 1997, Chicago. ISBN 0-226-19036-6)

- ^ Paul Thagard (1992) Conceptual revolutions p.259

- ^ Blechschmidt, Erich. The Beginnings of Human Life. Springer-Verlag Inc., 1977, pg. 32: "The so-called basic law of biogenetics is wrong. No buts or ifs can mitigate this fact. It is not even a tiny bit correct or correct in a different form, making it valid in a certain percentage. It is totally wrong."

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul; Richard Holm; Dennis Parnell. The Process of Evolution. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963, pg. 66: "Its shortcomings have been almost universally pointed out by modern authors, but the idea still has a prominent place in biological mythology. The resemblance of early vertebrate embryos is readily explained without resort to mysterious forces compelling each individual to reclimb its phylogenetic tree."

- ^ Mayr (1994) [1] in The Quarterly Review of Biology

- ^ Desmond 1989, pp. 52–53, 86–88, 337–340

- ^ Richardson and Keuck, "Haeckel’s ABC of evolution and development," p. 516

- ^ Richards, Robert J. 2008. The Tragic Sense of Life: Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle Over Evolutionary Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Pp. 136-142

- ^ a b Scott F Gilbert (2006). "Ernst Haeckel and the Biogenetic Law". Developmental Biology, 8th edition. Sinauer Associates. http://8e.devbio.com/article.php?id=219. Retrieved 2008-05-03. "Eventually, the Biogenetic Law had become scientifically untenable."

- ^ Toby White. "The Gill Arches: Meckel's Cartilage". paleos.com. http://www.palaeos.com/Vertebrates/Bones/Gill_Arches/Meckelian.html. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ Gerhard Medicus (1992). "The Inapplicability of the Biogenetic Rule to Behavioral Development" (PDF). Human Development 35 (1): 1–8. ISSN 0018-716X/92/0351/0001-0008. http://homepage.uibk.ac.at/~c720126/humanethologie/ws/medicus/block6/HumanDevelopment.pdf. Retrieved 2008-04-30. "The present interdisciplinary article offers cogent reasons why the biogenetic rule has no relevance for behavioral ontogeny. ... In contrast to anatomical ontogeny, in the case of behavioral ontogeny there are no empirical indications of 'behavioral interphenes, that developed phylogenetically from (primordial) behavioral metaphenes. ... These facts lead to the conclusion that attempts to establish a psychological theory on the basis of the biogenetic rule will not be fruitful."

- ^ "Making visible embryos: Forgery charges". University of Cambridge. http://www.hps.cam.ac.uk/visibleembryos/s4_2.html. Retrieved August 2011. "Rütimeyer’s ex-colleague, Wilhelm His, who had developed a rival, physiological embryology, which looked, not to the evolutionary past, but to bending and folding forces in the present. He now repeated and amplified the charges, and lay enemies used them to discredit the most prominent Darwinist. But Haeckel argued that his figures were schematics, not intended to be exact. They stayed in his books and were widely copied, but still attract controversy today."

- ^ "Wilhelm His, Sr". Embryo Project Encyclopedia. 2007. http://embryo.asu.edu/view/embryo:124762. Retrieved August 2011. "In 1874 His published his Über die Bildung des Lachsembryos, an interpretation of vertebrate embryonic development. After this publication His arrived at another interpretation of the development of embryos: the concrescence theory, which claimed that at the beginning of development only the simple form of the head lies in the embryonic disk and that the axial portions of the body emerge only later."

- ^ Herbert Spencer (1861). Education. pp. 5. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=98953755.

- ^ a b Gould 1977, pp. 156–158

- ^ Taruskin, Richard (2005). The Oxford History of Western Music. 4. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 358â361. ISBN 0-19-5222273-3.

- ^ Subin, Neil "Your Inner Fish" 2009

- Division of Biology and Medicine, Brown University. "Evolution and Development I: Size and shape". http://biomed.brown.edu/Courses/BIO48/30.S&S.HTML.

- Haeckel, E (1899). "Riddle of the Universe at the Close of the Nineteenth Century". http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/haeckel.html.

- Richardson, M., et al. (1997). "There is no highly conserved stage in the vertebrates: implications for current theories of evolution and development". Anatomy and Embryology 196 (2): 91–106. doi:10.1007/s004290050082. PMID 9278154.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1977). Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Cambridge Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63941-3.

- Desmond, Adrian J. (1989). The politics of evolution: morphology, medicine, and reform in radical London. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14374-0.

External links

Categories:- Biology theories

- History of evolutionary biology

- Obsolete scientific theories

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.