- Marie Stopes

-

Marie Carmichael Stopes, D.Sc., Ph.D.

Marie Stopes in her laboratory, 1904Born 15 October 1880 Died 2 October 1958 (aged 77) Nationality British Fields medicine Alma mater UCL (B.Sc., D.Sc.)

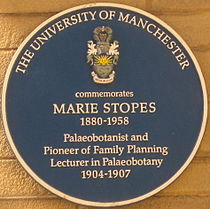

University of Munich (Ph.D.)Known for family planning Marie Carmichael Stopes (15 October 1880 – 2 October 1958) was a British author, palaeobotanist, campaigner for women's rights and pioneer in the field of birth control. Stopes edited the newsletter Birth Control News which gave anatomically explicit advice, and in addition to her enthusiasm for protests at places of worship this provoked protest from both the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church. Her sex manual Married Love, which was written, she claimed, while she was still a virgin, was controversial and influential.

The modern organisation that bears her name, Marie Stopes International, works in over 40 countries.[1] In 2008, there were 560 centres, including 5 in Bolivia, 9 in the UK, 10 in Australia, 25 in Kenya, 24 in South Africa, 48 in Pakistan and over 100 in Bangladesh.

Contents

Early work and education

Stopes was the daughter of Shakespeare scholar and women's rights campaigner Charlotte Carmichael Stopes and her husband Henry. She attended University College London as a scholarship student studying botany and geology, graduating with a first class B.Sc. in 1902. After carrying out research at University College London, she pursued further study at the University of Munich, receiving a Ph.D. in palaeobotany in 1904. Following this, Stopes earned a D.Sc. degree from University College London, becoming the youngest person in Britain to have done so. In 1903 she published a study of the botany of the recently dried-up Ebbsfleet River. In 1907 she went to Japan on a scientific mission, spending a year and a half at the Imperial University, Tokyo, exploring for fossil plants. She was also Fellow and sometime Lecturer in Palaeobotany at University College London and Lecturer in Palaeobotany at the University of Manchester (she held the post at Manchester from 1904 to 1907; in this capacity she became the first female academic of the University of Manchester).

Work in palaeobotany

During Stopes's time at Manchester, she studied coal and the collection of Glossopteris (seed ferns). This was an attempt to prove the theory of Eduard Suess concerning the existence of Gondwanaland or Pangaea. A chance meeting with Robert Falcon Scott (Scott of the Antarctic) during one of his fund-raising lectures brought a possibility of proving Suess's theory. Stopes's passion to prove Suess's theory led her to discuss with Scott the possibility of joining his next expedition to Antarctica. She failed to join the expedition, but Scott promised to bring back samples of fossils to provide confirmatory evidence for the theory. (The interior of Antarctica, being perpetually below 0°C, is not suitable for life, and the existence of fossils can be taken as providing inferential evidence of major changes in biological conditions in that region during geologic time.) Although Scott died during the expedition, his corpse was found; and located near the bodies of him and his companions were fossils from the Queen Maud Mountains that did indeed provide this evidence.

More information can be found at the Geological Society website concerning this area Cold Comfort.

Work in family planning

Stopes opened the UK's first family planning clinic, the Mothers' Clinic at 61, Marlborough Road, Holloway, North London on 17 March 1921.

In 1925 the Mothers' Clinic moved to Central London, where it remains to this day.

Stopes and her fellow family planning pioneers around the globe, like Dora Russell, played a major role in breaking down taboos about sex and increasing knowledge, pleasure and improved reproductive health. In 1930 the National Birth Control Council was formed.

Advocacy of eugenics

Stopes was a prominent campaigner for the implementation of policies inspired by eugenics, then not a discredited science. In her Radiant Motherhood (1920) she called for the "sterilisation of those totally unfit for parenthood [to] be made an immediate possibility, indeed made compulsory."

She contributed a chapter manifesto to The Control of Parenthood (1920), comprising a sort of manifesto for her circle of Eugenicists, arguing for a "utopia" to be achieved through "racial purification":

Those who are grown up in the present active generations, the matured and hardened, with all their weaknesses and flaws, cannot do very much, though they may do something with themselves. They can, however, study the conditions under which they came into being, discover where lie the chief sources of defect, and eliminate those sources of defect from the coming generation so as to remove from those who are still to be born the needless burdens the race has carried.[2]

However, in this tract, she argues that the leading causes of "racial degeneration" are "overcrowding" and sexually transmitted disease (ibid, p. 211). It concludes somewhat vaguely, that racial consciousness needs to be increased so that, "women of all classes [may] have the fear and dread of undesired maternity removed from them ..." to usher in the promised utopia, described throughout. (ibid, p. 221)

She also bemoaned the abolition of child labour for the lower classes:

"Crushed by the burden of taxation which they have not the resources to meet and to provide for children also: crushed by the national cost of the too numerous children of those who do not contribute to the public funds by taxation, yet who recklessly bring forth from an inferior stock individuals who are not self-supporting, the middle and superior artisan classes have, without perceiving it, come almost to take the position of that ancient slave population."

In 1935 Stopes attended the International Congress for Population Science in Berlin, held under the Nazi regime.[3] She was more than once accused of being anti-Semitic by other pioneers of the birth control movement such as Havelock Ellis.[4]

As came to public attention in years later, she was a personal as well as political follower of Adolf Hitler:

“Dear Herr Hitler, Love is the greatest thing in the world: so will you accept from me these (poems) that you may allow the young people of your nation to have them?” (letter from Marie Stopes to Hitler, August 1939[5]

After her son Harry married a myopic woman, Stopes cut him out of her will. The daughter-in-law—Mary Eyre Wallis, later Mary Stopes-Roe—was the daughter of the noted engineer Barnes Wallis. Stopes reasoned that prospective grandchildren might inherit the condition.[6]

Supporters of Stopes including Family Planning NSW (formerly the Racial Hygiene Association of New South Wales) generally concede that she made such remarks, but argue that they should be read in their historical context; i.e. that eugenics was more politically correct than 'family planning' at the time.[7]

Following the death of Marie Stopes in 1958, a large part of her personal fortune went to the Eugenics Society.[8]

Personal life

Stopes had a serious relationship with Japanese botanist Kenjiro Fujii (or Fugii), whom she met at the University of Munich in 1904 whilst researching her Ph.D. It was so serious that, in 1907, during her 1904-1910 tenure at Manchester University, she went to be with him in Japan, but the affair ended. In 1911 Stopes married Canadian geneticist Reginald Ruggles Gates. She later claimed that the marriage was never consummated. Her marriage to Gates was annulled in 1914.

In 1918 she married the financial backer of her most famous work, Married Love: A New Contribution to the Solution of the Sex Difficulties, Humphrey Verdon Roe, brother of Alliott Verdon Roe. Their son, the philosopher Harry Stopes-Roe, was born in 1924.[9]

Stopes died at her home in Dorking, Surrey, UK from breast cancer.

The modern Marie Stopes International organisation

From the 1920s onward, Marie Stopes gradually built up a small network of clinics that were initially very successful, but by the early 1970s were in financial difficulties. In 1975 the clinics went into voluntary receivership. The modern organisation that bears Marie Stopes' name was established a year later as an international Non-Governmental Organisation working on Sexual and Reproductive Health. The Marie Stopes International global partnership took over responsibility for the main clinic, and in 1978 it began its work overseas in New Delhi. Since then the organisation has grown steadily and today the MSI works in over 40 countries, has 452 clinics worldwide and has offices in London, Brussels, Melbourne and USA.

In 2006 alone, the organisation provided services to 4.6 million clients and by 2010 aims to protect 20 million couples from unplanned pregnancies and unsafe abortion.[citation needed]

Portland Museum

Marie Stopes founded Portland Museum, Dorset on the Isle of Portland, which opened in 1930, and acted as the museum's curator.[10] The cottage housing the museum was an inspiration behind The Well-Beloved, a novel by Thomas Hardy, who was a friend of Marie Stopes.[11]

Writings

- Marie Stopes (1918). Married Love. London: Fifield and Co.. ISBN 0192804324.

- Marie Stopes (1918). Wise Parenthood. London: Rendell & Co.. ISBN 0659905523.

- Marie Stopes (1910?). Botany The Modern Study of Plants. London: The People's Books.

Biographies

- Aylmer Maude (1924). The Authorized Life of Marie C. Stopes. London: Williams & Norgate.

- Keith Briant (1962). Passionate Paradox: The Life of Marie Stopes. New York: W.W. Norton & Co..

- Ruth Hall (1978). Marie Stopes: a biography. London: Virago, Ltd.. ISBN 0-86068-092-4.

- June Rose (1992). Marie Stopes and the Sexual Revolution. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-16970-8.

See also

Notes

- ^ [1]

- ^ Marie C. Stopes, "Racial and Imperial Aspects, (section) II", p. 207 et seq. (this quotation, see p. 208-09), in The Control of Parenthood, various authors, James Marchant, ed., 1920.

- ^ "Diane Paul, Controlling Human Heredity (1995), pp. 84-91", Virginia Tech.: Eugenics in Germany

- ^ http://www.bookrags.com/biography/marie-charlotte-carmichael-stopes-wog/

- ^ Gerald Warner, Marie Stopes is forgiven racism and eugenics because she was anti-life, in: The Telegraph, Aug. 28th, 2008 http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/news/geraldwarner/5051109/Marie_Stopes_is_forgiven_racism_and_eugenics_because_she_was_antilife/

- ^ Peter Pugh (2005) Barnes Wallis Dambuster. Thriplow: Icon ISBN 1-84046-685-5; p. 178

- ^ http://replay.waybackmachine.org/20090106130456/http://www.fpahealth.org.au/news/20061102_80.html

- ^ http://www.nndb.com/people/572/000024500/ "And upon her death a large portion of her fortune was bequeathed to the Eugenics Society."

- ^ Morpurgo, JE, Barnes Wallis, a Biography, pub 1972, Longman Group Ltd, London

- ^ Marie Stopes Pictures, Portland, Dorset, Steps in Time — Images Project (SITIP) archive.

- ^ Portland Museum, About Britain.

References

- "Dr. Marie Stopes". The Medico-legal Journal 26 (2): 70–1. . 1958. PMID 13622045.

- Taylor, L. (October 1971). "The unfinished sexual revolution (Marie Stopes)". Journal of Biosocial Science 3 (4): 473–92. doi:10.1017/S0021932000008233. PMID 4942965.

- Simms, M. (October 1975). "Marie Stopes Memorial Lecture 1975. The compulsory pregnancy lobby--then and now". The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 25 (159): 709–19. PMC 2157852. PMID 1104826. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2157852.

- Hall, L. A. (June 1983). "The Stopes collection in the Contemporary Medical Archives Centre at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine". The Society for the Social History of Medicine Bulletin 32: 50–1. PMID 11611236.

- Hall, L. A. (. 1985). ""Somehow very distasteful": doctors, men and sexual problems between the wars". Journal of Contemporary History 20 (4): 553–74. doi:10.1177/002200948502000404. PMID 11617291.

- Bacchi, C. (. 1988). "Feminism and the "eroticization" of the middle-class woman: the intersection of class and gender attitudes". Women's Studies International Forum 11 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(88)90006-4. PMID 11618316.

- Davey, C. (. 1988). "Birth control in Britain during the interwar years: evidence from the Stopes correspondence". Journal of Family History 13 (3): 329–45. doi:10.1177/036319908801300120. PMID 11621671.

- Fairley, A. (May. 1990). "The birth of birth control". Canadian Medical Association Journal 142 (9): 993–95. PMC 1451747. PMID 2183921. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1451747.

- Jones, G. (August 1992). "Marie Stopes in Ireland--the Mother's Clinic in Belfast, 1936-47". Social History of Medicine 5 (2): 255–77. PMID 11623088.

- Geppert, A. C. T. (January 1998). "Divine sex, happy marriage, regenerated nation: Marie Stopes's marital manual Married Love and the making of a best-seller, 1918-1955". Journal of the History of Sexuality 8 (3): 389–433. PMID 11620019.

- Fisher, Kate (. 2002). "Contrasting cultures of contraception: birth control clinics and the working-classes in Britain between the wars". Clio Medica 66: 141–57. PMID 12028675.

- Sakula, Alex (August 2003). "Plaques on London houses of medico-historical interest; Marie Stopes (1880–1958)". Journal of Medical Biography 11 (3): 141. PMID 12870036.

External links

- Marie Stopes International

- Marie Stopes International UK

- Marie Stopes International Australia

- Marie Stopes International South Africa

- Pictures of Marie Stopes and Thomas Hardy at her Portland, Dorset home

- 'The Colonisation of a Dried River Bed' - PDF file of Marie Stopes' 1903 article

- Archival material relating to Marie Stopes listed at the UK National Register of Archives

Categories:- 1880 births

- 1958 deaths

- British birth control activists

- Scottish writers

- Alumni of University College London

- Deaths from breast cancer

- Scottish suffragists

- Cancer deaths in England

- Scottish eugenicists

- Museum founders

- British curators

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.