- Noel F. Parrish

-

Noel Francis Parrish

Noel F. Parrish when a Lieutenant colonelBorn November 11, 1909

Versailles, KentuckyDied April 7, 1987 (aged 77)

Piney Point, MarylandPlace of burial Arlington National Cemetery Allegiance  United States of America

United States of AmericaService/branch  United States Air Force

United States Air ForceYears of service 1930–1964 Rank Brigadier General Commands held Tuskegee Airmen, Tuskegee Army Air Field Battles/wars World War II

Korean WarAwards Legion of Merit

Air MedalOther work Professor Noel Francis Parrish (November 11, 1909 – April 7, 1987) was a Brigadier General in the United States Air Force who was commander of a group of black airmen known as the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II. He was a key factor in the program's success and in their units being assigned to combat duty. Parrish was born and raised in the south-east United States; and joined the US Army in 1930. He served from 1930 until his retirement in 1964 as a Brigadier General, and is the namesake for Tuskegee's most prestigious award.

Contents

Early life and career

Parrish was the son of a Southern white minister; born in Versailles, Kentucky,[1] and spent parts of his youth living in Alabama and Georgia.[2] His birthplace is often listed as being in nearby Lexington, Kentucky.[3] He graduated from Cullman High School, Cullman, Alabama in 1924 and Rice Institute, Houston, Texas in 1928.[3] He quit graduate school after one year and decided to hitchhike to San Francisco. The lack of work meant hunger, so he chose to join the United States Army's 11th Cavalry Regiment as a private on July 30, 1930, serving in Monterey, California.[2][3][4][5]

After a year in the horse cavalry, Parrish became an aviation cadet in June 1931 and subsequently qualified as an enlisted pilot.[3][6] He competed flight training in 1932 and was assigned to the 13th Attack Squadron at Fort Crockett, near Galveston, Texas. One year later in September 1933 Parrish joined the Air Corps Technical School at Chanute Field, Illinois; later transferring to the First Air Transport Squadron at Dayton, Ohio. In July 1935 he rejoined the 13th Attack Squadron as assistant operations officer, then located at Barksdale Field, Louisiana. Parrish became a flying instructor at Randolph Field in April 1938, and by July 1939 he was a supervisor at the Air Corps Flying School in Glenview, Illinois.[3] Commissioned as a lieutenant in 1939,[7] Parrish attended the Air Command and Staff School at Maxwell Field, Alabama. As a captain, and still a student at Maxwell, his association with the Tuskegee Airmen began as in March 1941 when he was assigned as Assistant Director of Training of the Eastern Flying Training Command.[6] Upon graduation in June 1941, he chose to remain at Maxwell, and work with the Tuskegee Institute as a primary flight instructor.[8] On December 5, 1941, two days before the attack on Pearl Harbor,[9] he was promoted to Director of Training at Tuskegee Army Flying School in Alabama, assuming command of Tuskegee Army Air Field a year later, in December 1942.[3][4][8]

Tuskegee Experiment

Formation of the Tuskegee Experiment

Black Americans were not permitted to fly for the U.S. armed services prior to 1940. The creation of an all black pursuit squadron was brought about by pressure from civil rights organizations and the black press pressure, which aided in the establishment of the Tuskegee, Alabama base, in 1941. Members of that unit became known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Pilots as well as commanders, instructors, and maintenance and support staff which comprised the "Tuskegee Experiment."[10] There were approximately 14,000 ground support personnel at Tuskegee Field during the war along with almost 1,000 pilots graduating pilots; of which about 450 saw active combat during WW II.[1]

The Tuskegee Institute was selected by the military for the "Tuskegee Experiment" because of its commitment to aeronautical training. Tuskegee had the facilities, engineering and technical instructors, as well as a climate for year round flying. The first Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) students completed their instruction in May 1940. The Tuskegee program was then expanded and became the center for African-American aviation during World War II.[10] As Director of Training and later Tuskegee Field commander, Parrish, an old cavalry sergeant who had been commissioned in 1939 as a CPTP instructor while he was stationed near Chicago, played a key role in the program's success.[7]

Formation of the black air units was announced by Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson on January 16, 1941.[11] On March 19, 1941, the 99th Pursuit Squadron (Pursuit being an early WWII synonym for "Fighter") was established at Chanute Field in Rantoul, Illinois and activated three days later on March 22.[5][12][13] Over 250 enlisted men formed the first group of black Americans trained at Chanute in aircraft ground support trades. This small number became the core of other black squadrons subsequently formed at Tuskegee and Maxwell Fields in Alabama.[11][14] Later in 1941, the 99th Pursuit Squadron moved to Maxwell Field and then Tuskegee Field before deploy to combat in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations in 1943.[13]

Eleanor Roosevelt, who was interested in the Tuskegee aviation program, took a 40-minute flight around the base in a plane piloted by Charles "Chief" Anderson on April 19, 1941. Anderson was a self-taught black civilian and experienced aviator who learned how to fly before the war. He was hired by the Tuskegee program to be its Chief Flight Instructor.[15] Anderson has been referred to as the 'Ancient Mariner' of black aviation, having flown long before many of the new recruits were of age.[7] The Air Corps at that time, which had never had a single black member, was part of an army that possessed exactly two black Regular line officers at the beginning of the war: Brigadier Generals Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. and Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.[16]

Exercises at a Booker T. Washington monument located at the Tuskegee Institute commemorated the beginning of black American pre-flight training for military aviation. The first twelve candidates for officer-flier positions were cited by America’s black press as, "the cream of the country’s colored youth."[8] The first classes started at the institute, and flying lessons soon began at the Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) some approximately ten miles away. its having been built, government press releases recounted that the air field was developed and built by Negro contractors both skilled and unskilled.[2] Of the original class 5 students graduated in March 1942.[1][8][10]

The PTI3A Stearman was the first type of training plane to be used in teaching the new recruits. The AT6 Texan, and P-40 Warhawk followed as the aircraft of choice over time.[2] Much of the primary flight training was done at Moton Field at Tuskegee. Tuskegee trained over 1,000 black aviators during the war, about half of whom served overseas.[10]

Initial problems

Local white residents of the area objected almost immediately. They complained about black MPs challenging white people and patrolling the town while brandishing their military weapons. The first commanding officer, Major James Ellison, was supportive of his MPs; however, he was soon relieved of his command. A segregationist colonel replaced Ellison, and enforced the segregation both on and off the base. This prompted black newspapers to protest his assignment. The colonel was transferred with a promotion, and Noel Parrish then took command as 'director of training'.[2] The lack of assignments according to background and training led to an excess of non-aviation black officers without a mission. This became disparaging to morale, as the facility became overcrowded.[14][5] As there was little in the line of recreation, Parrish began to arrange for celebrities to visit and perform at the base. Lena Horne, Joe Louis, Ella Fitzgerald, Ray Robinson, Louis Armstrong, and Langston Hughes were among the many guests.[2] Parrish also desegregated the base to a much larger extent than his predecessors.[8]

Parrish demanded high standards of performance of his men, did not view race as an issue. Parrish felt that what mattered was professionalism and an individual's capacities, techniques, and judgement. Parrish held his black trainees to the same high standards of performance as whites; and those who did not meet those standards were failed out of the program.[2]

Active air units

Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. (L), Noel F. Parrish (C), and Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. (R) at Tuskegee during WWII.

Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. (L), Noel F. Parrish (C), and Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. (R) at Tuskegee during WWII.

The 99th Pursuit Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group were the only black air units that saw active combat during WWII. The 99th flew its first combat mission in June 1943, and later participated in the battle of Pantelleria. The Pantelleria attack forced the surrender of the ground garrison, due only to the air attack. The surrender to an air attack was the first of its kind.[17] The 332nd, which was a combination of comprising the 100th, the 301st, and the 302nd squadrons, first saw active combat in January 1944. The dive-bombing and strafing missions under Lieutenant Colonel Davis, Jr. were considered to be highly successful. Following a change in its mission to strategic bomber escort, the 99th was added to the 332nd in July 1944.[14][16]

In May 1942, the 99th Pursuit Squadron was renamed the 99th Fighter Squadron. It earned three Distinguished Unit Citations (DUC) during World War II. The DUCs were for operations at Pantelleria and Tunisia from May 30 – June 11, 1943, Monastery Hill near Cassino from May 12–14, 1944, and for successfully fighting off German jet aircraft on March 24, 1945. The mission was the longest bomber escort mission throughout the war.[18] [19] The 332nd also flew missions in Sicily, Anzio, Normandy, the Rhineland, the Po Valley and Rome-Arno and others. Pilots of the 99th once set a record for destroying five enemy aircraft in less than four minutes.[14]

Individual pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group also earned approximately 1000 awards and decorations. Their missions took them to Rome-Arno, Normandy, Rhineland, Romania, Northern and Southern France, and the American Theater Campaigns. The 332nd first saw combat in February 1944. Throughout various engagements over the course of the war, the 332nd was credited with destroying at least: 112 airborne enemy aircraft, 150 aircraft on the ground, over 600 train cars, over 40 barges/boats, and a German Navy destroyer. The destruction of the Navy destroyer was the first such accomplishment of its time.[14][19]

Although never seeing combat, The 477th Bombardment Group was activated in 1943, and was not completely manned until March 1945. The 553rd Fighter Replacement Training Squadron was also activated in 1943. Its mission was to provide replacement pilots for the 332nd. Both units began training at Selfridge Field, Michigan, but because of an unhealthy racial atmosphere in the local area the 477th was moved to Godman Field, Kentucky, then to Freeman Field, Indiana, while the 552rd was moved to Walterboro, South Carolina, where it was eventually inactivated. Its members were transferred to form a squadron of the Air Base Group. From its inception, the 477th was plagued with problems. When activated the unit had no established cadre to break-in new pilots and had no navigators/bombardiers to man crews. Within one year the 477th had 38 squadron or unit moves. In June 1945, the 477th was redesignated as the 477th Composite Group.[14][20]

Combat records

The Tuskegee Airmen compiled the following combat record: – 261 aircraft destroyed – 148 aircraft damaged – 15,533 sorties – 1,578 missions – 66 KIA – 95 Distinguished Flying Crosses awarded – 450 Pilots sent overseas. Their operational aircraft were, in succession: P-40 Warhawk, P-39 Airacobra, P-47 Thunderbolt, and P-51 Mustang fighter aircraft.[14]

Tuskegee experiment results

The "Tuskegee Experiment" was a tremendous success, in which Parrish played a significant role,[7] and proved that blacks could perform well in both leadership and combat roles. Parrish felt people should be judged by their capability, not their color.[7] He would return from Washington DC depressed because of the massive resistance to the Tuskegee program. For decades later at Tuskegee Airmen reunions, when Parrish's name was called everyone applauded with a standing ovation.[7] The experience of the AAF during World War II necessitated that the military review its policies on the utilization of black servicemembers. Confrontation, discussion, and coordination with both black and white groups led AAF leaders to the conclusion that active commitment, leadership, and equal opportunity produced a more cost-effective, viable military force. In 1948, President Harry Truman signed an Executive Order on equality of treatment and opportunity in the military, due in no small part to the successes of the Tuskegee Airmen.[14][16] Parrish was commander of Tuskegee Field from 1942–1946 and historians generally give him credit for improving morale, living conditions, relations between blacks and whites, and relations with local citizens.[14]

Parrish, stated in his memoirs that he often mediated between the Army officials, whites near Tuskegee who felt that the airmen were uppity, and the aviation trainees themselves.[5] Dr. Frederick D. Patterson, the third president of Tuskegee Institute, wrote to Parrish on September 14, 1944: "In my opinion, all who have had anything to do with the development and direction of the Tuskegee Army Air Field and the Army flying training program for Negroes in this area have just cause to be proud. . . . The development had to take place in a period of emergency and interracial confusion."[21]

After Tuskegee

Parrish stayed in command of the Tuskegee Airmen through the end of World War II in 1945 until August 20, 1946 when he was assigned to the Air University at Maxwell.[8][10] In August 1947 he entered the Air War College at Maxwell Field and graduated the following June. He then became deputy secretary of the Air Staff at Air Force Headquarters, Washington, D.C. and became a special assistant to the vice chief of staff there in January 1951. In September 1954 he became Air Deputy to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization Defense College, which was then located in Paris, France. On September 1, 1956 he became deputy director, Military Assistance Division, United States European Command, also in Paris. In May 1958 he returned to Air Force headquarters and became assistant for coordination to deputy chief of staff for Plans and Programs.[3][4]

He eventually became a Brigadier General—retiring from the Air Force on October 1, 1964.[4] His military decorations include the Legion of Merit and Air Medal.[3] He earned a PhD from his alma matar, Rice University,[9] and taught college history in Texas.[2] Parrish died on Tuesday, April 7, 1987 of cardiac arrest at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Piney Point, Maryland. At the service Lieutenant General Davis Jr. said "He may have been the only white person who believed that blacks could learn to fly airplanes."[4][9]

Family and personal life

Parrish was married twice, the second time to Florence Tucker Parrish-St.John, and had three stepsons.[9][22] He wrote magazine articles under a pen name and was interested in music and painting. Prior to being assigned to Tuskegee, he had no particular involvement nor concern with black Americans. When he was a youth, he hiked three miles to see where a black man had been lynched.[2] He recalled that when people heard of the project to train blacks pilots and mechanics he often heard “weird and worried kind of laughter” from white people and that a visiting British flying ace stated that it was better to have a “Messerschmitt on his tail than to try to teach a Negro to fly.”[2]

Legacy

According to a 2001 presentation which won top prize at a National History Day competition, 18-year-old Topeka High School student said that the Tuskegee Airmen, America's first black military pilots, helped lay the groundwork for the civil rights movement.[23] The most prestigious award of the association of Tuskegee Airmen (Tuskegee Airmen, Inc.)[24] and which is presented at their annual convention, was named 'the Brigadier General Noel F. Parrish Award'. For many years it was presented in person by his widow, Florence. She received the General Daniel James Jr. Distinguished Service/Achievement/Leadership Award at the 2010 convention.[22]

Historians generally give credit to Colonel Noel Parrish, Commander of Tuskegee Field from 1942 to 1946, for having improved morale by reducing the amount of segregation and overcrowding and improving relations with both blacks and whites in the town of Tuskegee.[14] The record of the Airmen became a major driver for President Harry S Truman's decision, in 1948, to desegregate the U.S. military.[14][16]

See also

- 92nd Infantry Division

- 93rd Infantry Division

- 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion "Triple Nickle"

- 761st Tank Battalion

- Aerial warfare

- Bessie Coleman

- Executive Order 9981

- List of African American Medal of Honor recipients

- Military history of African Americans

- Red Ball Express

- Strategic bombing during World War II

- The Port Chicago 50

References

- ^ a b c "Governor Fletcher, Kentucky Transportation Cabinet honor first African-American military pilots". Kentucky Transportation Cabinet. http://migration.kentucky.gov/newsroom/aome/tuskegee.htm. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Smith, Gene (May/June 1995 1995). "Colonel Parrish’s Orders". American History 46 (3). http://www.americanheritage.com/content/colonel-parrish%E2%80%99s-orders?page=show. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Brigadier General Noel F. Parrish". United States Air Force. http://www.af.mil/information/bios/bio.asp?bioID=6687. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Noel F. Parrish". Arlington National Cemetery. http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/nfparrish.htm. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Francis, Charles F. (1997). The Tuskegee Airmen: The Men Who Changed a Nation. Boston: Branden Book. pp. 9, 14–15, 58–61, 68, 214, 220, 224, 231–233, 237–240, 247–248, 250–252, 256–260, 273, 364, 370–371, 419, 466. ISBN 0-8283-2029-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=VyuedRwZre8C&pg=PA411&lpg=PA411&dq=Edward+M.+Thomas+tuskegee+died&source=bl&ots=L8DBxNT1eR&sig=uxA-omTiTIZ8WogUlI8tsM8RKts&hl=en&ei=OtHyTcyoGMnLgQeA0enFCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CEIQ6AEwBg#v=snippet&q=parrish&f=false.

- ^ a b "Milestones". Air University, Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base Montgomery, Alabama. http://afehri.maxwell.af.mil/Pages/milestone.htm. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Tuskegee Experiment". Ranger 95. http://ranger95.com/airforce/airforces/tuskegee_experiment.htm. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Tuskegee Airmen Chronology" (PDF). Air Force Historical Research Agency. http://www.afhra.af.mil/shared/media/document/AFD-100413-023.pdf. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Gen. Noel Parrish, 77, Trained Black Aviators". The Chicago Tribune via United Press International. April 12, 1987. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1987-04-12/news/8701270779_1_tuskegee-airmen-black-fliers-black-aviationl. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Tuskegee Airmen—Text Version". National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/tuskegee/airprint.htm. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ a b "Illinois has a rich history of Afro-American Aviation". Chanute Air Museum. http://www.aeromuseum.org/exhibitsCurrent_99th.html. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ Moye, J. Todd (2010). Freedom Flyers: The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 26–37. ISBN 978-0195386554.

- ^ a b "FHRA 99 FTS Page". Air Force Historical Research Agency. http://www.afhra.af.mil/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=10562. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Black Americans in Defense of Our Nation". Sam Houston State University. http://www.shsu.edu/~his_ncp/AfrAmer.html. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ "Charles Anderson". Hill Air Force Base. http://www.hill.af.mil/library/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=5833. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Celebrating African Americans in Aviation". San Diego Air & Space Museum. http://www.sandiegoairandspace.org/exhibits/african_american_exhibit/military-inspirations.php. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ Molony, Brigadier C.J.C.; with Flynn, Captain F.C. (R.N.); Davies, Major-General H.L. & Gleave, Group Captain T.P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO:1973]. Butler, Sir James. ed. The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume V: The Campaign in Sicily 1943 and The Campaign in Italy 3 September 1943 to 31 March 1944. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. p. 49. ISBN 1-845740-69-6.

- ^ "99th Flying Training Squadron History". United States Air Force. http://www.randolph.af.mil/library/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=5896. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ a b "Escort Excellence". National Museum of the Air Force. http://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/factsheets/factsheet_print.asp?fsID=15471&page=2. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ "The Freeman Field Mutiny: A Study In Leadership" (PDF). Air University, Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base Montgomery, Alabama. http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/acsc/97-0429.pdf. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ "African American Odyssey: The Depression, The New Deal, and World War II". Libray of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/aaohtml/exhibit/aopart8.html. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ a b "CSAF: Legacy of Tuskegee Airmen lives on in today's Airmen". Defense Media Activity-San Antonio, United States Air Force. http://www.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123215985. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ Lee, Floyd (July 29, 2001). "THS senior honors Tuskegee Airmen". The Topeka Capital-Journal. http://cjonline.com/stories/072901/com_thstuskegee.shtml. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ "Tuskegee Airmen, Inc.". Tuskegee Airmen, Inc.. http://www.tuskegeeairmen.org. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

Further reading

- Bucholtz, Chris (2007). 332nd Fighter Group: Tuskegee Airmen. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1846030447, 9781846030444.

- Oral history transcript-tape not available, Dryden, Charles W. (March 17, 1982). Black Military Oral History Project. Washington, D.C.: Howard University. http://www.founders.howard.edu/moorland-spingarn/ORAL.htm.

- Oral history transcript-tape not available, Parrish, Noel F. (May 1982). Black Military Oral History Project. Washington, D.C.: Howard University. http://www.founders.howard.edu/moorland-spingarn/ORAL.htm.

External links

- Images of Tukegee airmen, photos, paintings etc.

- "Red-Tail Angels": The Story of the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II

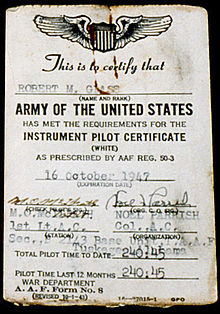

- Photo and biography of pilot Robert M. Glass

- Freedom Flyers: The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II

- The Tuskegee Airmen (1995)

- The Tuskegee Airmen (documentary film) Public Broadcasting Service.

- Funeral Program for Tuskegee Airman Cassius Harris, African American Funeral Programs from the East Central Georgia Regional Library

- The Red Tail Project

- African Americans in the U.S. Army

- National Museum of the United States Air Force: Eugene Jacques Bullard

- "Tuskegee Airmen: Brett Gadsden Interviews J. Todd Moye", Southern Spaces September 30, 2010.

- Interview with historian Todd Moye regarding the Tuskegee Airmen on "New Books in History"

- Contemporary newsreel about "Negro Pilots" – YouTube

Stations Bizerte · Depienne · Enfidaville · Massicault · Oudna · Pont du Fahs · Sainte Marie du Zit · SolimanAmendola · Bari · Castelltuccio · Cattolica · Celone · Cerignola · Fano · Foggia · Gioia del Colle · Grottaglie · Giulia · Lesina · Lucera · Madna · Manduria · Marcianise · Mondolfo · Pantanella · Piagiolino · Pisa · Rimini · Salsosa · San Giovanni · San Pancrazio · San Severo · Spinazzola · Sterparone · Tortorella · Torremaggiore · Torretto · Triolo · Venosa · Vincenzo

Units Wings5th Bombardment · 47th Bombardment · 49th Bombardment · 55th Bombardment · 304th Bombardment · 305th Fighter (P) · 306th FighterGroupsBombardment2nd Bombardment · 97th Bombardment · 98th Bombardment · 99th Bombardment · 301st Bombardment · 376th Bombardment · 449th Bombardment · 450th Bombardment · 451st Bombardment · 454th Bombardment · 455th Bombardment · 456th Bombardment · 459th Bombardment · 460th Bombardment · 461st Bombardment · 463rd Bombardment · 464th Bombardment · 465th Bombardment · 483rd Bombardment · 484th Bombardment · 485th BombardmentFighter 1st Fighter · 14th Fighter · 31st Fighter · 52nd Fighter · 82nd Fighter · 325th Fighter · 332nd FighterUnited States Army Air Forces

First · Second · Third · Fourth · Fifth · Sixth · Seventh · Eighth · Ninth · Tenth · Eleventh · Twelfth · Thirteenth · Fourteenth · Fifteenth · TwentiethUnited States in World War II Home Front American music during World War II • United States aircraft production during World War II • Greatest Generation

American WomenWomen Airforce Service Pilots • Women's Army Corps• Woman's Land Army of America • Rosie the RiveterMilitary participation Army (Uniforms) • Army Air Force • Marine Corps • Navy • Service medals (Medal of Honor recipients)

EventsList of Battles • Attack on Pearl Harbor • Normandy landings • Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and NagasakiMinoritiesDiplomatic participation Categories:- American military personnel of World War II

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- United States Air Force generals

- 1909 births

- 1987 deaths

- People from Woodford County, Kentucky

- Rice University alumni

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.