- Music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

-

While the contributions of the Russian nationalistic group The Five were important in their own right in developing an independent Russian voice and consciousness in classical music, the compositions of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky became dominant in 19th century Russia, with Tchaikovsky becoming known both in and outside Russia as its greatest musical talent. His formal conservatory training allowed him to write works with Western-oriented attitudes and techniques, showcasing a wide range and breadth of technique from a poised "Classical" form simulating 18th century Rococo elegance to a style more characteristic of Russian nationalists or a musical idiom expressly to channel his own overwrought emotions.[1]

Even with this compositional diversity, the outlook in Tchaikovsky's music remains essentially Russian, both in its use of native folk song and its composer's deep absorption in Russian life and ways of thought.[1] Writing about Tchaikovsky's ballet The Sleeping Beauty in an open letter to impressario Sergei Diaghilev that was printed in the Times of London, composer Igor Stravinsky contended that Tchaikovsky's music was as Russian as Pushkin's verse or Glinka's song, since Tchaikovsky "drew unconsciously from the true, popular sources" of the Russian race.[2] This Russianness of mindset ensured that Tchaikovsky would not become a mere imitator of Western technique. Tchaikovsky's natural gift for melody, based mainly on themes of tremendous eloquence and emotive power and supported by matching resources in harmony and orchestration, has always made his music appealing to the public. However, his hard-won professional technique and an ability to harness it to express his emotional life gave Tchaikovsky the ability to realize his potential more fully than any other Russian composer of his time.[3]

Contents

Reception and reputation

Although Tchaikovsky's music has always popular with audiences, it has at times been judged harshly by musicians and composers. However, his reputation as a significant composer is now generally regarded as secure.[4] His music has won a significant following among concert audiences in the United States, Great Britain and many other countries that is second only to the music of Beethoven.[5]

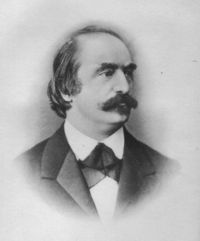

A prime asset in the popularity of Tchaikovsky's music is what Harold C. Schonberg terms "a sweet, inexhaustible, supersensuous fund of melody ... touched with neuroticism, as emotional as a scream from a window on a dark night."[6] This combination of supercharged melody and surcharged emotion polarized listeners, with popular appeal of Tchaikovsky's music counnterbalanced by critical disdain of it as vulgar and lacking in elevated thought or philosophy.[5] Viennese music critic Eduard Hanslick wrote about the Violin Concerto that he had heard music which stank to the ear.[7] William Forster Abtrop, normally disinclined towards much contemporary music, wrote more positively about Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony in his notes for a Boston Symphony Orchestra performance of the work:

Tchaikovsky is one of the leading composers, some think the leading composer, of the present Russian School. He is fond of emphasizing the peculiar character of Russian melody in his works, plans his compositions in general on a large scale, and delights in strong effects. He has been criticized for the occasional excessive harshness of his harmony, for now and then descending to the trivial and the tawdry in his ornamental figuration, and also for a tendency to develop comparatively insignificant material to inordinate length. But, in spite of the prevailing wild savagery of his music, its originally and the genuineness of its fire and sentiment are not to be denied.[8]

This sentiment did not stop Abtrop from writing about the same work in the Boston Evening Transcript:

[The Fifth Symphony] is less untamed in spirit than the composer's B-flat minor [Piano Concerto], less recklessly harsh in its polyphonic writing, less indicative of the composer's disposition to swear a theme's way through a stone wall.... In the Finale we have all the untamed fury of the Cossack, whetting itself for deeds of atrocity, against all the sterility of the Russian steppes. The furious peroration sounds like nothing so much as a hoard of demons struggling in a torrent of brandy, the music growing drunker and drunker. Pandemonium, delerium tremens, raving, and above all, noise were confounded![9]

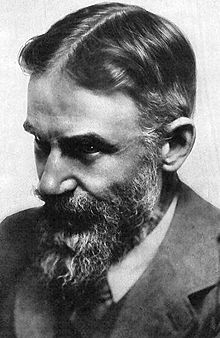

George Bernard Shaw, in reviewing the Fourth Symphony when the composer conducted it in London in 1893, was less pictorial than Abtrop but likewise found fault:

The most notable merit of the symphony is the freedom from the frightful effeminacy of most modern works of the romantic school. It is worth remarking, too, considering the general prevalence in recent music of restless modulation for modulation's sake, that Tschaikowsky [sic] often sticks to the same key rather longer than the freshness of his melodic resources warrants. He also insists upon some of his conceits—for instance, that Kentish Fire interlude in the slow movement—more than they sound worth to me, but perhaps fresh young listeners with healthy appetites would not agree with me.[10]

More recently, Tchaikovsky's music has received a professional reevaluation, with musicians reacting more favorably to its tunefulness and craftsmanship. His orchestration remains a source of admiration, while the last three numbered symphonies are now considered a successful compromise between the classical-era requirements of the form and the demand for new forms dictated by post-Romantic musical and extramusical concerns. Those three symphonies, along with two of his concertos, his three ballets, the Romeo and Juliet fantasy-overture, the 1812 Overture, the Marche Slave and two of his operas, retain their popularity. Almost as popular are the Serenade for Strings, Francesca da Rimini and the Capriccio Italien.[11]

Creative range

Tchaikovsky sought expressive value in music that was immediately comprehensible and appreciable — in other words, what was apparent on the surface. He admired Bizet's Carmen for exactly this reason. "This music has no pretensions to profundity, but it is so charming in its simplicity, so vigorous, not contrived but instead sincere, that I learned all of it from beginning to end almost by heart." He felt the high demands of Wagner's music on its audiences conflicted with these ideals, and his objections to Brahms were similar. Tchaikovsky was however fascinated by the music of Mozart, which he felt combined simplicity with profundity.[12]

Tchaikovsky's formal conservatory training allowed him to expand on this range of musical interests by giving him the means to write works with a corresponding breadth, utilizing Western-oriented attitudes and techniques. He may be best known in writing works in a musical style which allowed him to channel his own overwrought emotions. However, he was also able to compose with a graceful formality approximating 18th century Rococo elegance, as shown in The Queen of Spades and the Variations on a Rococo Theme, as well as a style more characteristic of Russian nationalists, as in the Second Symphony.[13]

Program music

Despite his reputation as a "weeping machine,"[11] self-expression was not a central principle for Tchaikovsky. In a letter to von Meck dated December 5, 1878, he explained there were two kinds of inspiration for a symphonic composer, a subjective and an objective one:

In the first instance, [the composer] uses his music to express his own feelings, joys, sufferings; in short, like a lyric poet he pours out, so to speak, his own soul. In this instance, a program is not only not necessary but even impossible. But it is another matter when a musician, reading a poetic work or struck by a scene in nature, wishes to express in musical form that subject that has kindled his inspiration. Here a program is essential.... Program music can and must exist, just as it is impossible to demand that literature make do without the epic element and limit itself to lyricism alone.

Correspondingly, the large scale orchestral works Tchaikovsky composed can be divided into two categories—symphonies in one category and other works such as symphonic poems and program music in the other. Both categories were equally valid.[14] Program music such as Francesca da Rimini or the Manfred Symphony was as much a part of the composer's artistic credo as the expression of his "lyric ego."[15] The music in each category should be looked upon strictly on its own parameters. In doing so, practices such as labeling all his works based on literary subjects as confessional music would be unwarranted.[16]

The character of Hermann in the opera The Queen of Spades is a case in point. His musical characterization has sometimes been mentioned as an expression of the composer's morbidity and suicidal tendencies. However, Tchaikovsky's own letters and diary entries would seem to disprove this notion, showing that he did not identify with Hermann. His diary entry for March 2, 1890, when he had just completed the opera, shows a characteristic mixture of empathy and detachment. "Wept terribly when Hermann breathed his last. The result of exhaustion, or maybe it is truly good."[16]

Pre-Romantic styled works

There is also a group of compositions which fall outside the dichotomy of program music versus lyrical ego, where he hearkens toward pre-Romantic aesthetics. Works in this group include the orchestral suites, Capriccio Italien and the Serenade for Strings.[17] He displays his clearest link to pre-Romantic sensitivities in retrospective works such as the Variations on a Rococo Theme and Mozartiana, a collection of orchestrations based on Mozart piano pieces and a Liszt transcription of a Mozart work. The Violin Concerto also looks back to pre-Romantic aesthetics. While Tchaikovsky does not follow classical practice, most notably in the lack of a double exposition in the first movement, he also does not follow the conventions of other 19th-century violin concertos. It is not written as a virtuosic work for virtuosity's sake, like Paganini's concertos, nor virtuosity used to express a symphonic concept, as in the Brahms Violin Concerto. The tone of the orchestral introduction could almost be considered classicist; the same is true for the transparent orchestration, with the orchestra itself relegated for the most part to background for the soloist.[18]

Capriccio italien, evoking Italian urban folklore, was the continuation of a tradition begun with Haydn and Mozart.[18] The Serenade for Strings was intended as a tribute to Mozart. While not copying any style, Tchaikovsky attempts to convert the spirit of the Classical approach into his own compositional idiom. The Serenade's unique tone comes from a subtle balance between Tchaikovsky's lyrical sentimentality and his attention to classical measure and clarity.[19]

Captivating nightmares

In The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker, Tchaikovsky conjures a "world of captivating nightmares" of E.T.A. Hoffmann, as Alexandre Benois phrases it, "a mixture of strange truth and convincing invention."[20] Another glimpse of this world comes earlier, with the Second Orchestral Suite. The unsuspecting would not expect a radical musical adventure in a movement titled Rêves d'enfant (A Child's Dream). Nothing in the movement's opening hints at the strange, even unnerving sound world that Tchaikovsky conjures, one more akin to Stravinsky than to Tchaikovsky.[21] As for The Nutcracker, the music setting the scene in Act One once the guests have left shows Tchaikovsky's skill at orchestrating dark fantasy; none of his other works is the scoring so important in setting the tone. Especially striking is the use of harp and wind instruments.[22]

Whimsy and delicate fantasy

Tchaikovsky also had a lighter side. He could be whimsical, such as in the Chacteristic Dances that make up most of Act Two of The Nutcracker and, several years earlier, the Marche miniature (originally titled March of the Lilliputians) from the First Orchestral Suite. He could also be good-natured, almost tongue-in-cheek, such as in the scherzo and gavotte which follow the Marche miniature in the First Orchestral Suite and the Danse baroque which concludes the Second Orchestral Suite. There are also moments of delicate, almost ethereal fantasy, as in the scherzo of the Manfred Symphony, where the orchestration dictates the music directly in terms of colors and textures into a world that is alluring, fragile and elusive.[23]

Passé-ism

In The Sleeping Beauty and The Queen of Spades, Tchaikovsky reconstructs the imperial grandeur of the 18th-Century world. Tchaikovsky sets The Sleeping Beauty in the realm of Louis XIV, a nostalgic tribute to the French influence of 18th-century Russian music and culture. This may have been dictated at least in part by the source of the story, Charles Perrault's fairy tale La Belle au bois dormant. Nevertheless, the Francophilia that Alexandre Benois and his friends in the St. Petersburg intelligentsia heard in the music made them embrace it all the more readily.[25]

The Queen of Spades, based on the Pushkin story, evokes the St. Petersburg of Catherine the Great—an era where the Russian capital was fully integrated with, and played a major role, in the culture of Europe. Infusing the opera with rococo elements (Tchaikovsky himself describes the ballroom scenes as a "slavish imitation" of 18th-Century style), he uses the story's layers of ghostly fantasy to conjure up a dream world of the past.[26]

At the same time, Benois emphasized, Tchaikovsky's talent for writing in this vein was more than simply stylization. (Tchaikovsky was, however, also highly gifted at stylization, as shown by his Serenade for Strings and Fourth Orchestral Suite, subtitled Mozartiana.) Tchaikovsky's evocative powers gave timelessness and immediacy, making the past seem as though it were the present. Benois calls this quality "passé-ism."[27]

Public considerations

Tchaikovsky believed that his professionalism in combining skill and high standards in his musical works separated him from his contemporaries in The Five. He shared several of their ideals, including an emphasis on national character in music. His aim, however, was linking those ideals to a standard high enough to satisfy Western European criteria. His professionalism also fueled his desire to reach a broad public, not just nationally but internationally, which he would eventually do.[28]

He may also have been influenced by the almost "eighteenth-century" patronage prevalent in Russia at the time, still strongly influenced by its aristocracy.[29] Tchaikovsky found no aesthetic conflict in playing to the tastes of his audiences. The patriotic themes and stylization of 18th-century melodies in his works lined up with the values of the Russian aristocracy.[30]

Tchaikovsky made full use of the emotional and symbolic possibilities of the Russian anthem "God Save the Tsar" in several commemorative works, including two of his most popular compositions, the Marche Slave and the 1812 Overture. Tchaikovsky wrote Marche Slave in support of Pan-Slavism. This was one of the most cherished ideas of imperial Russia. When Serbia rebelled against Turkish rule in 1876, they elicited great support in Russia. Performances of the Marche Slave, with its Serbian folk melodies provoked outbursts of patriotism. The 1812 Overture likewise glorified the greatest military and political victory of the Romanov dynasty, in the Patriotic War against Napoleon.

While Tchaikovsky's musical cosmopolitanism led him to be favored by many Russian music-lovers over the "Russian" harmonies and styles of Mussorgsky, Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov,[31] he nonetheless frequently adapted Russian traditional melodies and dance forms in his music, which enhanced his success in his home country. The success in St. Petersburg at the premiere of his Third Orchestral Suite may have been due in large part to his concluding the work with a polonaise.[30][32] He also used a polonaise for the final movement of his Third Symphony.[33]

Tchaikovsky used a Russian folk song in the finale of the First Symphony and a Ukrainian folk song in the finale of the Second. In both cases, as with the Third, this had undertones of glorifying the Russian empire and the victories of Russian arms.[34] Even the finales of the Fourth and Fifth Symphonies could be argued to be in imperial nationalistic vein, as patriotic and heroic appeals—the Fourth by repeating the opening motto at a climactic point and the Fifth with a version of the opening melody of the introduction transposed to a major key.[35]

Compositional style

Melody

Tchaikovsky's melodies range from Western style to folksong stylizations and occasionally folksongs themselves. He also sometimes employs the practice of repetition which is characteristic of certain Russian folk songs, extending themselves by constant variations on a single motif. More usually, however, his repetitions reflect the sequential practices of Western practices, and could be extended at immense length. At times these repetitions could build into an emotional experience of almost unbearable intensity. He also allows modal practices to influence his original melodies repeatedly, though not very strongly. Dance tunes, especially waltzes, are his most characteristic melodies and tunes, filling not only his ballets but also compositions in other genres except church music. Also prevalent are impassioned cantilenas often possessing strong contours, with a full-blooded emotion that is often supported by a harmony of complementary expressive tensions.[36]

Rhythm

Tchaikovsky experimented occasionally with unusual meters. More usually, as typified by his dance tunes, he employs a very Russian sense of dynamic rhythm to provide a firm, essentially regular meter. This meter sometimes becomes the main expressive agent in some movements due to its being used so vigorously. He also employs a strong metrical drive as synthetic propulsion in large-scale symphonic movements in place of organic growth and movement.[36]

Harmony

Tchaikovsky also practiced a wide range of harmony, from the Western harmonic and textural practices of his first two string quartets to the unorthodox progressions in the center of the finale of the Second Symphony. This finale also contains one of the few times Tchaikovsky employed the whole tone scale in the bass; this was a practice more typically used by the Five. Usually Tchaikovsky uses relatively conventional harmonic progressions, such as the circle of fifths in the first love theme of Romeo and Juliet. Frequently, however, these progressions involve a liberality in the use of pedals which is typical in the work of Russian composers as well as a decorative use of chromaticism.[36]

Orchestration

Tchaikovsky wrote most of his music for the orchestra. His musical textures therefore became increasingly conditioned by the orchestral colors he employed, especially after the Second Orchestral Suite. While he was grounded in Western orchestral practices, Tchaikovsky preferred bright and sharply differentiated orchestral coloring in the tradition established by Glinka and followed typically by Russian composers since then. He tends to exploit primarily the treble instruments for their fleet delicacy, though he balances this tendency with a matching exploration of the darker, even gloomy sounds of the bass instruments.[36]

Compositions

Operas

Tchaikovsky completed ten operas, although one of these (Undina) is mostly lost and another (Vakula the Smith) exists in two significantly different versions. He also began or at least considered writing at least 20 others; he once declared that to refrain from writing operas was a heroism he did not possess.[37] In the West his most famous operas are Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades. While the other eight he finished are seldom performed outside Russia, the operas on the whole embody an enormous mass of music considered by some far too beautiful and interesting to be ignored. Moreover, Tchaikovsky's search for operatic subjects, along with his views on their nature and treatment and his own work on librettos, throw considerable light on his creative personality.[38]

Symphonies

See also: Symphonies by TchaikovskyTchaikovsky's earlier symphonies are generally optimistic works of nationalistic character. The First, considered by some critics to be the weakest of the set,[39] is a work conventional in form but already strongly colored by its composer's individuality, exuding a richness in melodic invention while exuding a Mendelssohnian charm and grace.[40] The Second Symphony is among the more accessible of Tchaikovsky's works and exists in two versions. While the latter version is the one generally performed today, Tchaikovsky's friend and former student Sergei Taneyev considered the earlier one to be finer compositionally speaking.[41] The Third, the only symphony Tchaikovsky completed in a major key, is written in five movements, similar to Robert Schumann's Rhenish Symphony, shows Tchaikovsky alternating between writing in a more orthodox symphonic manner and writing music as a vehicle to express his emotional life;[42] with the introduction of dance rhythms into every movement except the slow one, the composer widens the field of symphonic contrasts both within and between movements.[43]

With the last three numbered symphonies, Tchaikovsky became one of the few composers in the late 19th century who could impose his personality upon the symphony to give the form new life. A key crisis facing composers like Tchaikovsky was reconciling the more personal, dramatic and empirical forms and heightened emotional statements that developed in Romanticism with the classical structure of the symphony.[44] Tchaikovsky's individual contribution to the development of symphonic thought was the discovery and integration of new and violent contrasts, not only between the first subject in the tonic key and the contrasting second subject in the dominant but also between thematic and harmonic contrasts.[45] As a result, the later symphonies became intensely dramatic. The Fourth Symphony is considered a breakthrough work in terms of emotional depth and complexity, particularly in its very large opening movement. The Fifth Symphony is a more regular work, though perhaps not a more conventional one.[46] The Sixth Symphony, generally interpreted as a declaration of despair, is a work of prodigious originality and power and is perhaps one of Tchaikovsky's most consistent and perfectly composed works.[47] These symphonies are recognized as highly original examples of symphonic form and are frequently performed. Manfred, written between the Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, is also a major piece, as well as a demanding one. The music is often very tough, the first movement completely original in form, while the second movement proves diaphanous and seemingly unsubstantial but absolutely right for the program it illustrates.[48]

Ballets

While Tchaikovsky admitted that he could write well in an opera only when he became personally involved with his characters, his rich gifts for melody in general and a specific flair for writing memorable dance tunes, along with his ready response to the atmosphere of a theatrical situation, equipped him ideally as a ballet composer. Nonetheless, his first ballet, Swan Lake, is not a consistently successful piece. In passages where Tchaikovsky focused on dramatic action, he showed his aptitude for music of considerable substance and scale. However, he also had to make concessions to the expectations of the Russian public for decorative spectacle, with lengthy divertissements in two of the ballet's four acts diverting action from the main plot.[49] Still, while less consistently rich than the music Tchaikovsky would write for The Sleeping Beauty, many parts of Swan Lake' showcase his gift for melody. The oboe solo associated with Odette and her swans, which first appears at the end of Act 1, is especially memorable.[50]

Tchaikovsky considered his next ballet, The Sleeping Beauty, one of his finest works. The structure of the scenario proved more successful than that of Swan Lake. While the prologue and first two acts contain a certain number of set dances, they are not designed for gratuitous choreographic decoration but have at least some marginal relevance to the main plot. These dances are also far more striking than their counterparts in Swan Lake, as several of them are character pieces from fairy tales such as Puss in Boots and Little Red Riding Hood, which elicited a far more individualized type of invention from the composer. Likewise, the musical ideas in these sections are more striking, pointed and precise. This characterful musical invention, combined with a structural fluency, a keen feeling for atmosphere and a well-structured plot, makes The Sleeping Beauty perhaps Tchaikovsky's most consistently successful ballet.[51]

The Nutcracker, on the other hand, is one of Tchaikovsky's best known works. While it has been criticized as the least substantial of the composer's three ballets, it should be remembered that Tchaikovsky was restricted by a rigorous scenario supplied by Marius Petipa. This scenario provided no opportunity for the expression of human feelings beyond the most trivial and confined Tchaikovsky mostly within a world of tinsel, sweets and fantasy. Yet, at its best, the melodies are charming and pretty, and by this time Tchaikovsky's virtuosity at orchestration and counterpoint ensured an endless fascination in the surface attractiveness of the score.[52]

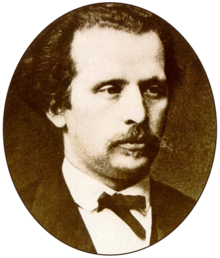

Concertos

Two of Tchaikovsky's concertos were rebuffed by their respective dedicates but became among the composer's best-known works. The First Piano Concerto suffered an initial rejection by its intended dedicate, Nikolai Rubinstein, as notably recounted three years after the fact by the composer. The work went instead to pianist Hans von Bülow, whose playing had impressed Tchaikovsky when he appeared in Moscow in March 1874. Bulow premiered the work in Boston in October 1875. Rubinstein eventually championed the work himself.[53] Likewise, the Violin Concerto was rejected initially by noted virtuoso and pedagogue Leopold Auer, was premiered by another soloist (Adolph Brodsky), then belatedly accepted and played to great public success by Auer. In addition to playing the concerto himself, Auer would also teach the work to his students, including Jascha Heifetz and Nathan Milstein.[54] Altogether, Tchaikovsky wrote three piano concertos, one violin concerto and concertante works for solo cello, piano and violin with orchestra or piano accompaniment. The best-known of these smaller works is the Variations on a Rococo Theme for solo cello and orchestra.

Chamber music

Chamber music does not figure prominently in Tchaikovsky's compositional output. Other than a number of student exercises, it consists of three string quartets, a piano trio and a string sextet, along with three works for violin and piano. While all these works contain some excellent music, the First String Quartet, with its famous Andante cantabile slow movement, shows such mastery of quartet form that some consider it the most satisfying of Tchaikovsky's chamber works in its consistency of style and artistic interest.[55] While the Second String Quartet is less engaging than the First and less characterful than the Third, its slow movement is a substantial and particularly affecting piece.[56] Some critics consider the Third String Quartet the most impresssive, especially for its elegiac slow movement.[57]

Also elegiac is the Piano Trio, written in memory of Nikolai Rubinstein—a point which accounts for the prominence of the piano part. The work is in two actual movements, the second a large set of variations including a fugue and a long summing-up variation serving as the equivalent of a third movement.[58] Had Tchaikovsky written this work as a piano quartet or piano quintet, he would have availed himself of a string complement well able to play complete harmony and could therefore have been allotted autonomous sections to play. With only two stringed instruments, this option was not available. Instead, Tchaikovsky treats the violin and cello as melodic soloists, with the piano both conversing with them and providing harmonic support.[59]

The String Sextet, entitled Souvenir de Florence, is considered by some to be more interesting than the Piano Trio, better music intrinsically and better written.[60] None of Tchaikovsky's other chamber works has a more positive opening, and the simplicity of the main section of the second movement is even more striking. After this very affecting music, the third movement progresses at least initially into a fresh, folksy world. Even more folksy is the opening of the finale, though Tchaikovsky takes this movement in a more academic direction with the incorporation of a fugue.[61] This work has also been played in arrangements for string orchestra.

Solo piano music

Tchaikovsky wrote over a hundred-odd piano works over the course of his creative life. His first opus comprised two piano pieces, while he completed his final set of piano works after he had finished sketching his last symphony.[62] Except for a piano sonata written while he was a composition student and a second much later in his career, Tchaikovsky's solo piano works consist of character pieces.[63] While his best known set of these works is The Seasons,[64] the compositions in his last set, the Eighteen Pieces, Op. 72, are extremely varied and at times surprising.[65]

Some of Tchaikovsky's piano works can be challenging technically; nevertheless, they are mostly charming, unpretentious compositions intended for amateur pianists.[64] It would therefore be easy to dismiss the entire œuvre as mediocre and merely competent. While this view could hold true to some point, there is more attractive and resourceful music in some of these pieces than one might be inclined to expect.[62] The difference between Tchaikovsky's pieces and many other salon works are patches of striking harmony and unexpected phrase structures which may demand some extra patience but will not remain unrewarded from a musical standpoint. Many of the pieces have titles which give imaginative pointers on how they should be played.[66]

Songs

Tchaikovsky wrote 103 songs. While he may not be remembered as a composer of lieder, he produced a larger number of superior works than their comparative neglect would suggest, often concentrating into a few pages a musical image that would seem to ideally match the substance of the text. The songs are extremely varied and encompass a wide range of genres—pure lyric and stark drama; solemn hymns and short songs of everyday life; folk tunes and waltzes. Tchaikovsky is most successful when writing on the subject of love and its loss or frustration[67]

Technically, the songs are marked by several features: artistic simplicity, artlessness of musical language, variety and originality of melody and richness of accompaniment. The songs helped cross-pollinate the composer's work in other genres, with many of his operatic arias closely related to them.[68] While "None but the Lonely Heart" may be the one of his finest songs, as well as perhaps the best-known in the West,[69] the Six Romances, Op. 65 and the Six Romances, Op. 73 are especially recommendable.[65]

See also

- Tchaikovsky in popular media

Notes

- ^ a b Brown, New Grove, 18:606.

- ^ Stravinsky, Igor, "An Open Letter to Diaghilev," The Times, London, October 18, 1921. As quoted in Holden, 51.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:606-7, 628.

- ^ Brown, New Grove (1980), 18:628-9.

- ^ a b Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:169.

- ^ Schonberg, 366.

- ^ Hanslick, Eduard, Musical Criticisms 1850-1900, ed. and trans. Henry Pleasants (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1963).

- ^ Boston Symphony Orchestra program book, October 21–22, 1892. As Quoted in Steinberg, Symphony, 630.

- ^ Boston Evening Transcript, October 23, 1892. As quoted in Steinberg, Symphony, 631

- ^ Shaw, George Bernard, Shaw's Music (London: Bodley Head, 1981), ii, 905. As quoted in Holden, 338.

- ^ a b Schonberg, 367.

- ^ Maes, 138.

- ^ Blom, 71; Brown, New Grove, 18:606.

- ^ Wood, 75.

- ^ Maes, 154.

- ^ a b Maes, 139.

- ^ Maes, 154-155.

- ^ a b Maes, 156.

- ^ Maes, 157.

- ^ Benois, Alexandre, Moi vospominaniia (My Reminiscences), vol. 1 (bks. 1-3), 603. As quoted in Volkov, 124.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The man and His Music, 260.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music, 405.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music, 295-296.

- ^ This illustration was commissioned for "Les Contes de Perrault" (Paris: J. Hetzel, 1867), Tchaikovsky's source for the story of The Sleeping Beauty.

- ^ Volkov, St. Petersburg, 123-124).

- ^ Figis, 274.

- ^ Volkov, St. Petersburg, 124.

- ^ Maes (2002), 73.

- ^ In this patronage patron and artist often met on equal terms. Dedications of works to patrons were not gestures of humble gratitude but expressions of artistic partnership. The dedication of the Fourth Symphony to von Meck is known to be a seal on their friendship. Tchaikovsky's relationship with Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich bore creative fruit in the Six Songs, Op. 63, for which the grand duke wrote the words. Maes, 139-141.

- ^ a b Maes, 137.

- ^ Volkov, 96.

- ^ The polonaise was imported into Russia near the end of the 18th century by Jozef Kozlowski, a Polish composer who served in the Russian Army. Kozlowski's greatest musical successes were with his polonaises. He wrote a triumphal polonaise on a text by Derzhavin, "Thunder of Victory, Resound," to celebrate the Russian victory over the Turks in the Ukraine. After that, the polonaise became the preeminent ceremonial gesture in Russia. It became an expression of tsarist patriotism and imperialism. Figis, 274; Maes, 78.

- ^ This led to a misunderstanding when the symphony was performed in the West. Western nations, more familiar with the polonaise as used by Frédéric Chopin, subtitled the symphony Polish. They considered the finale an expression of a Polish longing for freedom and national resurgence. The real meaning of the polonaise in the symphony was the exact opposite. Like the finales of Tchaikovsky's first two symphonies, the finale of the Third was meant to appeal to the patriotic sentiment of the Russian aristocracy—precisely the people who wanted to keep the Poles yoked to the tsarist regime. Maes, 78-79.

- ^ Volkov, 113.

- ^ Maes, 163-164.

- ^ a b c d Brown, New Grove, 18:628.

- ^ Harold Rosenthal & John Warrack, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera, 2nd ed. (1979), page 492.

- ^ Abraham, 124.

- ^ Keller, 343.

- ^ Keller, 343; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 48-9.

- ^ Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 70-71.

- ^ Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 81.

- ^ Keller, 344-5.

- ^ Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 133.

- ^ Keller, The Symphony, 1:346-7.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 337.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 417.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 293.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:613-14.

- ^ Evans, 194.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:624.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:625.

- ^ Steinberg, Concerto, 474-6.

- ^ Steinberg, Concerto, 484-5.

- ^ Mason, 104.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 80.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 107.

- ^ Mason, 110.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 239.

- ^ Mason, 111.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 383.

- ^ a b Brown, The Final Years, 408.

- ^ Dickinson, 115.

- ^ a b Brown, Man and Music, 118.

- ^ a b Brown, Man and Music, 431n.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 181-2.

- ^ Alshvang, 198; Warrack, Tchaikovsky 58.

- ^ Alshvang, 198-9.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 55

Bibliography

- ed. Abraham, Gerald, Music of Tchaikovsky (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1946). ISBN n/a.

- Abraham, Gerald, "Operas and Incidental Music"

- Alshvang, A., tr. I. Freiman, "The Songs"

- Cooper, Martin, "The Symphonies"

- Dickinson, A.E.F., "The Piano Music"

- Evans, Edwin, "The Ballets"

- Mason, Colin, "The Chamber Music"

- Wood, Ralph W., "Miscellaneous Orchestral Works"

- Brown, David, ed. Stanley Sadie, The New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillian, 1980), 20 vols. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840-1874 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978). ISBN 0-393-07535-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years, 1874-1878, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983). ISBN 0-393-01707-9.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Years of Wandering, 1878-1885, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1986). ISBN 0-393-02311-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885-1893, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991). ISBN 0-393-03099-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music (New York: Pegasus Books, 2007). ISBN 0-571-23194-2.

- Figes, Orlando, Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002). ISBN 0-8050-5783-8 (hc.).

- Hanson, Lawrence and Hanson, Elisabeth, Tchaikovsky: The Man Behind the Music (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 66-13606.

- Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995). ISBN 0-679-42006-1.

- Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Mochulsky, Konstantin, tr. Minihan, Michael A., Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 65-10833.

- Poznansky, Alexander Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991). ISBN 0-02-871885-2.

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai, Letoppis Moyey Muzykalnoy Zhizni (St. Petersburg, 1909), published in English as My Musical Life (New York: Knopf, 1925, 3rd ed. 1942). ISBN n/a.

- Schonberg, Harold C. Lives of the Great Composers (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. 1997).

- Steinberg, Michael, The Symphony (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Tchaikovsky, Modest, Zhizn P.I. Chaykovskovo [Tchaikovsky's life], 3 vols. (Moscow, 1900–1902).

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr, Perepiska s N.F. von Meck [Correspondence with Nadzehda von Meck], 3 vols. (Moscow and Lenningrad, 1934–1936).

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr, Polnoye sobraniye sochinery: literaturnïye proizvedeniya i perepiska [Complete Edition: literary works and correspondence], 17 vols. (Moscow, 1953–1981).

- Volkov, Solomon, tr. Bouis, Antonina W., St. Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1995). ISBN 0-02-874052-1.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 78-105437.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). SBN 684-13558-2.

- Wiley, Roland John, Tchaikovsky's Ballets (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). ISBN 0-198-16249-9.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Life Music List of compositions · Musical style · Operas · Symphonies · Romeo and Juliet · 1812 Overture · The Nutcracker · Swan Lake · The Sleeping Beauty · Marche Slave · Manfred Symphony · Francesca da Rimini · Capriccio Italien · Serenade for StringsCategories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.