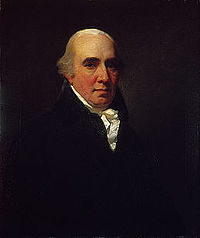

- Dugald Stewart

-

For the Canadian politician, see Dugald Stewart (politician).

Dugald Stewart FRSE FRS (November 22, 1753 – June 11, 1828) was a Scottish Enlightenment philosopher and mathematician. His father, Matthew Stewart (1715–1785), was professor of mathematics in the University of Edinburgh (1747–1772).

Contents

Life and works

Dugald Stewart was born and educated in Edinburgh at the Royal High School and the university, where he read mathematics and moral philosophy under Adam Ferguson. In 1771, in the hope of gaining a Snell Exhibition and proceeding to Oxford to study for the English Church, he went to the University of Glasgow to attend the classes of Thomas Reid. To Reid he later owed his theory of morality, repaying the debt by giving to Reid's views the advantage of his admirable style and academic eloquence. In Glasgow, Stewart boarded in the same house as Archibald Alison, author of the Essay on Taste, and a lasting friendship sprang up between them.

After a single session in Glasgow, at the age of nineteen Dugald was summoned by his father, whose health was beginning to fail, to conduct his mathematical classes in the University of Edinburgh. After acting thus for three years Dugald was elected professor of mathematics in conjunction with his father in 1775. Three years later Adam Ferguson was appointed secretary to the commissioners sent out to the American colonies, and at his urgent request Stewart lectured as his substitute. Thus during the session 1778–1779, in addition to his mathematical work, he delivered an original course of lectures on morals.

In 1783 he married Helen Bannatyne, who died in 1787, leaving an only son, Colonel Matthew Stewart. In his early years he was influenced by Lord Monboddo, with whom he corresponded.

In 1785 he succeeded Ferguson in the chair of moral philosophy, which he filled for twenty-five years, making it a centre of intellectual and moral influence. Young men were attracted by his reputation from England, Europe and America. Among his pupils were Lord Palmerston, Sir Walter Scott, Francis Jeffrey, Henry Thomas Cockburn, Francis Horner, Sydney Smith, John William Ward, Lord Brougham, Dr. Thomas Brown, James Mill, Sir James Mackintosh and Sir Archibald Alison.

Stewart's course on moral philosophy embraced, besides ethics proper, lectures on political philosophy or the theory of government, and from 1800 onwards a separate course of lectures was delivered on political economy, then almost unknown as a science. Stewart's enlightened political teaching was sufficient, in the times of reaction succeeding the French Revolution, to draw upon him the undeserved suspicion of disaffection to the constitution. The summers of 1788 and 1789 he spent in France, where he met Suard, Degbrando, Raynal, and came to sympathize with the revolutionary movement.

In 1790 Stewart married Helen D'Arcy Cranstoun, sister of George Cranstoun. His second wife was well-born and accomplished, and he was in the habit of chewing his nails to her criticism whatever he wrote. They had a son and a daughter, but the son's death in 1809 was a severe blow to his father, and brought about his retirement from the active duties of his chair. Before that, however, Stewart had not been idle as an author. As a student in Glasgow he wrote an essay on Dreaming. In 1792 he published the first volume of the Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind; the second volume appeared in 1814, the third not till 1827. In 1793 he printed a textbook, Outlines of Moral Philosophy, which went through many editions; and in the same year he read before the Royal Society of Edinburgh his account of the Life and Writings of Adam Smith.

Similar memoirs of Robertson the historian and of Reid were afterwards read before the same body and appear in his published works. In 1805 Stewart published pamphlets defending John Leslie against the charges of unorthodoxy made by the presbytery of Edinburgh. In 1806 he received in lieu of a pension the nominal office of the writership of the Edinburgh Gazette, with a salary of £300. When the shock of his son's death incapacitated him from lecturing during the session of 1809–1810, his place was taken, at his own request, by Dr Thomas Brown, who in 1810 was appointed conjoint professor. On the death of Brown in 1820 Stewart retired altogether from the professorship, which was conferred upon John Wilson, better known as "Christopher North".

From 1809 onwards Stewart lived mainly at Kinneil House, Bo'ness, which was placed at his disposal by the Duke of Hamilton. In 1810 appeared the Philosophical Essays, in 1814 the second volume of the Elements, in 1811 the first part and in 1821 the second part of the "Dissertation" written for the Encyclopædia Britannica Supplement, entitled "A General View of the Progress of Metaphysical, Ethical, and Political Philosophy since the Revival of Letters."

In June 1814 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society [1]

Dugald Stewart Monument, Edinburgh

Dugald Stewart Monument, Edinburgh

In 1822 he was struck with paralysis, but recovered a fair degree of health, sufficient to enable him to resume his studies. In 1827 he published the third volume of the Elements, and in 1828, a few weeks before his death, The Philosophy of the Active and Moral Powers. He died in Edinburgh, where he was buried in Canongate Churchyard. Additionally, and of greater public note, a monument to his memory was erected on Calton Hill. His memory is also honoured by the newly constructed Dugald Stewart Building at the University of Edinburgh, on Charles Street.

Influence

Stewart was principally responsible for making the "Scottish philosophy" predominant in early 19th-century Europe.[1] In the second half of the century, as with so much of Enlightenment thought, it came to be seen as superseded, and Stewart's work as merely the reproduction of his master Reid, a gross exaggeration. He upheld Reid's psychological method and expounded the "common-sense" doctrine, which was attacked by the two Mills. But part of his originality lay in his readiness to depart from the pure Scottish tradition and incorporate elements of moderate empiricism and the French ideologists (Laromiguière, Cabanis and Destutt de Tracy). It is important to notice the energy of his declaration against the argument of ontology, and also against Condillac's sensationalism. Kant, he confessed, he could not understand.[2] But his reputation rests as much on his inspiring eloquence, populism, and the beauty of his style as on original work.[2]

Stewart's works were edited in 11 vols. (1854–1858) by Sir William Hamilton and completed with a memoir by John Veitch. Matthew Stewart (his eldest son) wrote a life in Annual Biography and Obituary (1829), republished privately in 1838. For his philosophy see McCosh, Scottish Philosophy (1875), pp. 162–173; A Bain, Mental Science, pp. 208, 313 and app. 29, 65, 88, 89; Moral Science, pp. 639 seq.; Sir L Stephen, English Thought in the XVIII Century.

See also

References

- ^ "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. http://www2.royalsociety.org/DServe/dserve.exe?dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqCmd=Show.tcl&dsqDb=Persons&dsqPos=3&dsqSearch=%28Surname%3D%27stewart%27%29. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ Jonathan Friday (2005): Dugald Stewart on Reid, Kant and the Refutation of Idealism, British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 13:2, 263–286

External links

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Dugald Stewart", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Stewart_Dugald.html.

- Dugald Stewart at The Online Library of Liberty

Figures in the Age of Enlightenment by country or region Notable figures America (English) America (Latin) England Edward Gibbon · Thomas Hobbes · Samuel Johnson · Edmund Burke (Irish born) · John Locke · Isaac Newton · Robert WalpoleFrance Germany Greece Hungary Italy Low Countries Poland-Lithuania Portugal Romanian States Russia Scandinavia Scotland Joseph Black · James Boswell · Robert Burns · Adam Ferguson · Francis Hutcheson · David Hume · James Hutton · Lord Kames · Lord Monboddo · James Macpherson · Thomas Reid · William Robertson · Adam Smith · Dugald Stewart · James Watt

Serbia Spain Ukraine Related topics

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Categories:- 1753 births

- 1828 deaths

- 18th-century philosophers

- 18th-century Scottish people

- People from Edinburgh

- People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

- Academics of the University of Edinburgh

- Burials at the Kirk of the Canongate

- Enlightenment philosophers

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Historians of Scotland

- Members of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh

- Scottish historians

- Scottish mathematicians

- Scottish philosophers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.