- Yellow-bellied marmot

-

Yellow-bellied marmot

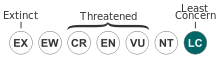

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Rodentia Family: Sciuridae Genus: Marmota Subgenus: Petromarmota Species: M. flaviventris Binomial name Marmota flaviventris

(Audubon and Bachman, 1841)Subspecies M. f. avara

M. f. dacota

M. f. flaviventris

M. f. luteola

M. f. nosophora

M. f. notioros

M. f. obscuraThe yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris), also known as the rock chuck, is a ground squirrel in the marmot genus.

Contents

Description

Yellow-bellied marmots are generally small to medium sized. The post-hibernation weight of adults averages 3.9 kg for males and 2.8 kg for females.[2] The total body length is 470-700 mm with a 130-220 mm long tail. Males tend to be longer in length than females.[3] Marmots have thick bodies and short broad heads. The dental formula is[2]

. Their ears are small and well furred. The feet have five digits with stoat and slightly curved claws. The thumb is rudimentary but bears a nail. The palms of the paws have five pads with three at the base of the digits and the posterior pad being oval in shape.[2] The marmot has soft, dense somewhat woolly underfur, especially on the back and sides. Its outer guard hairs are longer and coarser and cover the entire body. The overall color is yellowish brown to tawny and has light tips and darker subterminal bands of many dorsal guard hairs giving it a frosted appearance.[2] Marmots also have distinct yellow speckles on the sides of their necks and white between their eyes. Coloration, however, can vary even within subspecies.[4] Partial or fully melanistic individuals are common in populations from the southern Rockies from Wyoming to New Mexico.[5]

. Their ears are small and well furred. The feet have five digits with stoat and slightly curved claws. The thumb is rudimentary but bears a nail. The palms of the paws have five pads with three at the base of the digits and the posterior pad being oval in shape.[2] The marmot has soft, dense somewhat woolly underfur, especially on the back and sides. Its outer guard hairs are longer and coarser and cover the entire body. The overall color is yellowish brown to tawny and has light tips and darker subterminal bands of many dorsal guard hairs giving it a frosted appearance.[2] Marmots also have distinct yellow speckles on the sides of their necks and white between their eyes. Coloration, however, can vary even within subspecies.[4] Partial or fully melanistic individuals are common in populations from the southern Rockies from Wyoming to New Mexico.[5]Marmots molt every year during the summer. When emerging form hibernation in late winter or spring, marmots are in long and fully fresh pelage. This pelage fades rapidly during the spring and summer and becomes more coarser in texture.[2] Molting begins earlier in low altitude populations which emerge from hibernation before populations at higher elevations. Male and non-lactating female begin molting before nursing females, within a population.[2] Marmot often retain some hairs on the rump and tail for more than a year and these hairs become coarser and paler than the rest of the hairs.

Ecology

The yellow-bellied marmot has a wide distribution in the western North America. It ranges from south-central British Columbia and the very south of Alberta southward though the Columbia Plateau, Snake River Plains and the Great Basin and reaches its southern limit in the southern Sierra Nevada and White Mountains of California, the Toquina and Pine Valley Mountains in the Great Basin of Nevada and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in New Mexico.[2] The marmot is semi-fossorial, usually inhabiting vegetated talus slops or rock outcrops in meadows. Marmots use rocks as support for burrows as well as sunning and observation posts. Burrows are usually located on well-drained slopes.[2] In the northern limits of its range, the marmot is found only in warm, arid habitats at low to medium level elevations.[6] In the more central parts of its range, the marmot lives in woodland and forests openings in the alpine zone. At the southern limit of its range, the marmot is found only at higher elevations, usually at above 2000 m.[2]

Yellow-bellied marmots are herbivorous. A variety of plant species are eaten, including grasses, flowers and forbs.[7] In addition, large numbers of seeds are eaten in the late summer.[2] Caterpillars of the sphinx moth have been found in marmot stomachs. Predation on marmot has not often been observed. Likely predators include that wolves, coyotes, badgers, bobcats, hawks and owls. Predation seems to be more of a problem for peripheral marmots more so than colonial marmots.[2] Cannibalism has also been documented.[8]

Hibernation lasts around eight months, at least in the Gothic-Crested Butte of Colorado, lasting from early September to May and represents around 60% of the total time spent underground.[9] Hibernation is a time of great mortality for marmots of all age groups.[10] Young marmots lose around 50% of their body weight during hibernation and as such they must obtain a threshold weight during hibernation.[2] Young more they will weigh more at the time of hibernation the earlier they are weaned. Marmots that live at lower elevations in the northwestern United States emerge from hibernation from late February to mid-March or, depending on the elevation, later.[2] For the adults, estivation begins in early June and they are followed by the young around twenty days later.

The main entrance of a marmot burrow, which may number up to three, extends to a depth of about 0.6m with the main passageway extending another 3.8-4.4m horizontally into the hillside.[2] There are several short blind tunnels that branch from the main passageway and from the nest chamber with the latter being located at the burrow beneath a large rock. Marmots use for burrows as nurseries for the young, as refuges from predators and conspecifics and as sites for hibernation.[11] In Gothic, Colorado marmots spend 80% of their lives in their burrows.[9] The environment in the burrow is relativity stable as the temperature deviates little from 10° from June to October.[12]

Marmot activity peaks in mornings and late afternoons. They typically emerge from their burrows soon after dawn. They may defecate and spend short times sunning and grooming.[2] Foraging peaks in mid-morning and is followed by sunning and sometimes by more grooming and long periods of time in the burrow.

Life history

Yellow-bellied marmots live in colonies or as single or paired individuals.[7] Marmots that live in colonies are residents of harems which consist of one adult territorial male, several adult females and their offspring.[13] Single marmots, pairs or single females with young live on peripheral habitat or satellite sites that have limited numbers of burrows.[11] There appears to be a continuum of sites, ranging from those harboring one individual to those harboring one harem to those harboring multiple harems.[10] In Gothic area, is was found that 75% of marmots lived in colonies, while 16% inhabited satellite sites and 7% were transients.[11] Marmots that live that satellite sites tend to have lower reproductive rates. It appears that harems are more reproductively fit.[13] However, it is also possible that predator defense is more likely to be the advantage in living in a harem.[14]

Marmots communicate primarily with auditory or visual signals. However, there are three basic vocalizations: whistles, screams and tooth chatters.[15] There are different variants of the whistle which may be used for alert, alarm or threat. Screams are responses to fear or excitement and teeth chatters are used as threats.[15] Harem males will defend their territories and females against peripheral or transient males that may try to invade. However actual fights are rare and most turnovers of territories occur when a harem male dies and a top peripheral male takes over. Both sexes have cheek and anal glands and will mark during conflict situations.[16] This may be an expression of dominance rather than territoriality and may also have a reassurance function. Females within a harem tend to be related and have strong social bonds. The younger females will assist the breeding females in raising the young. There also appears to be sexual repression of daughters by their mothers.[17]

Mating begins after marmots emerge from hibernation. Both males and females reach sexual maturity in their second year. Gestation lasts around 30 days.[2] Litter size may average around 4 young, at least in the Gothic area.[13] The young usually remain in the burrow for their first month before emerging.[10] Females are the primary caregivers for the young. As yearlings, males will disperse and so will most females.[10] However some females may find it more beneficial to stay with their mothers for another year without inferring in their mothers’ next litter.[2] Dispersing males will try to claim a territory of their own. Harem males will act aggressively towards maturing males and this contributes to their dispersal. Also the aggressive behavior of females with litters may contribute to the dispersal of both sexes.[18]

Status and human interactions

This species is not of conservation concern and its range includes several protected areas. There are no major threats to this species.[1] Marmots generally pose no threat to humans and shy away from contact, but can be a nuisance in wilderness areas. Marmots enjoy chewing on rubber,[19] which can disable cars and destroy sleeping pads and hiking poles.

References

- ^ a b Linzey, A. V. & NatureServe (Hammerson, G.) (2008). Marmota flaviventris. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 6 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Frase B. A., Hoffman R. S. (1980) Marmota flaviventris. Mammalian Species 135:1-8.

- ^ Nee J. A. (1969) "Reproduction in a Population of Yellow-Bellied Marmots (Marmota flaviventris)", Journal of Mammalogy 50(7):756-65.

- ^ Armstrong D. M. (1972) "Distribution of mammals in Colorado", Mongr. Mus. Nat. Hist., Univ. Kansas, 3:X + 1-415.

- ^ Armitage K. B. (1961) "Frequency of melanism in the golden-mantled marmot," Journal of Mammalogy. 42:100-101.

- ^ Soper J. D. (1964) The mammals of Alberta. Hamly Press, Edmonton, Alberta.

- ^ a b Svendsen G. E. (1973) Behavioral and environment factors in the spatial distribution and population dynamics of a yellow-bellied marmot population. Unpubl. Ph.D. dissert., Unvi. Kansas, Lawrence.

- ^ Armitage, K. B., Johns, D. & Andersen, D. C. (1979) "Cannibalism among yellow-bellied marmots", J. Mamm. 60, 205-207.

- ^ a b Svendsen G. E. (1976) "Stricture and location of burrows of yellow-bellied marmot", Southwestern Nat 20:487-94.

- ^ a b c d Armitage K. B., Downhower J. F. (1974) Demography of yellow-bellied marmot populations. Ecology 55:1233-45.

- ^ a b c Svendsen G. E. (1974) Behavioral and environmental factors in the spatial distribution and population dynamics of a yellow-bellied marmot population. Ecology 55:760-71.

- ^ Kilgore D. L., Jr. (1972) Energy dynamics of the yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris): a hibernator. Unpubl. Ph.D. dissert. Univ. Kansas, Lawerence.

- ^ a b c Downhower J. F., Armitage K. B. (1971) The yellow-bellied marmot and the evolution of polygamy. Amer, Nat. 105:355-70.

- ^ Elliot P. F. (1975) "Longevity and the evolution of polygamy", Amer. Nat. 109:281-87.

- ^ a b Waring G. H. (1966) "Sounds and communications of the yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris)", Anim. Behav. 14:177-83.

- ^ Armitage K. B. (1976) "Scent marking by yellow-bellied marmot", J Mamm. 57:538-84.

- ^ Armitage, K. B., Schwartz O. A. (2000) "Social enhancement of fitness in yellow-bellied marmots", Proceedings for the National Academy of Science 97:12149-152.

- ^ Downhower J. F. (1968) Factors affecting dispersal of yearling yellow-bellied marmots. Unpubl. Ph.D. dissert., Unvi. Kansas, Lawrence.

- ^ http://www.summitpost.org/homers-nose/154602

- "Marmota flaviventris". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180140. Retrieved 18 March 2006.

- Thorington, R. W. Jr. and R. S. Hoffman. 2005. Family Sciuridae. Pp. 754-818 in Mammal Species of the World a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder eds. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

External links

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Marmots

- Mammals of Canada

- Mammals of the United States

- Fauna of the Western United States

- Fauna of the Sierra Nevada (U.S.)

- Animals described in 1841

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.