- Snakes and Ladders

-

For other uses, see Snakes and Ladders (disambiguation)."Chutes and Ladders" redirects here. For the song by Korn, see Shoots and Ladders (song).

Snakes and Ladders

Game of Snakes and Ladders, India, 19th century, Gouache on clothPlayers 2+ Age range 3+ Setup time Negligible Playing time 15–45 minutes Random chance Entirely Skill(s) required Counting Snakes and Ladders (or Chutes and Ladders) is an ancient Indian board game regarded today as a worldwide classic.[1] It is played between two or more players on a game board having numbered, gridded squares. A number of "ladders" and "snakes" (or "chutes") are pictured on the board, each connecting two specific board squares. The object of the game is to navigate one's game piece from the start (bottom square) to the finish (top square), helped or hindered by ladders and snakes, respectively. The historic version had root in morality lessons, where a player's progression up the board represented a life journey complicated by virtues (ladders) and vices (snakes).

The simplicity and seesawing nature of the contest make the game popular with younger children, but the lack of any skill component makes the game less appealing for older players.[citation needed]

Contents

Board geometry

The size of the grid (most commonly 8×8, 10×10, or 12×12) varies from board to board, as does the exact arrangement of the snakes and ladders, with both factors affecting the duration of play. As a result, the game can be represented as a state-absorbing Markov chain.[2] Random dice rolls determine game piece movement in the traditional form of the game.

History

Snakes and Ladders originated in India as part of a family of dice board games, including pachisi (modern day Ludo). It was known as moksha pAtam or vaikunthapaali or paramapada sopaanam (the ladder to salvation).[3] The game made its way to England and was sold as Snakes and Ladders, then the basic concept was introduced in the United States as Chutes and Ladders (an "improved new version of England's famous indoor sport")[2] by game pioneer Milton Bradley in 1943.[3]

The game as popularly played in ancient India was known as Moksha Patam, and emphasized the role of fate or karma. A Jain version, Gyanbazi, dates to the 16th century. The game was called Leela and reflected the Hinduism consciousness surrounding everyday life. Impressed by the underlying ideals of the game, a newer version was introduced in Victorian England in 1892.

Moksha Patam was associated with traditional Hindu philosophy contrasting karma and kama, or destiny and desire. It emphasized destiny, as opposed to games such as pachisi, which focused on life as a mixture of skill (free will[4]) and luck. The game has also been interpreted and used as a tool for teaching the effects of good deeds versus bad. The ladders represented virtues such as generosity, faith, and humility, while the snakes represented vices such as lust, anger, murder, and theft. The morality lesson of the game was that a person can attain salvation (Moksha) through doing good, whereas by doing evil one will inherit rebirth to lower forms of life. The number of ladders was less than the number of snakes as a reminder that a path of good is much more difficult to tread than a path of sins. Presumably the number "100" represented Moksha (salvation). In Andhra Pradesh, snakes and ladders is played in the name of Vaikuntapali.

In the original game the squares of virtue are: Faith (12), Reliability (51), Generosity (57), Knowledge (76), and Asceticism (78). The squares of vice or evil are: Disobedience (41), Vanity (44), Vulgarity (49), Theft (52), Lying (58), Drunkenness (62), Debt (69), Rage (84), Greed (92), Pride (95), Murder (73), and Lust (99).

Playing

Each player starts with a token on the starting square (usually the "1" grid square in the bottom left corner, or simply, the imaginary space beside the "1" grid square) and takes turns to roll a single die to move the token by the number of squares indicated by the die roll. Tokens follow a fixed route marked on the gameboard which usually follows a boustrophedon (ox-plow) track from the bottom to the top of the playing area, passing once through every square. If, on completion of a move, a player's token lands on the lower-numbered end of a "ladder", the player moves his token up to the ladder's higher-numbered square. If he lands on the higher-numbered square of a "snake" (or chute), he must move his token down to the snake's lower-numbered square.

If a player rolls a 6, he may, after moving, immediately take another turn; otherwise play passes to the next player in turn. If a player rolls three consecutive 6s, he must return to the starting square (grid "1") and may not move again until rolling another 6. The player who is first to bring his token to the last square of the track is the winner.

A variation exists where a player must roll the exact number to reach the final square (hence winning). Depending on the particular variation, if the roll of the die is too large the token remains in place.

Specific editions

The most widely known edition of Snakes and Ladders in the United States is Chutes and Ladders from Milton Bradley (which was purchased by the game's current distributor Hasbro). It is played on a 10×10 board, and players advance their pieces according to a spinner rather than a die. The theme of the board design is playground equipment—children climb ladders to go down chutes. The artwork on the board teaches a morality lesson, the squares on the bottom of the ladders show a child doing a good or sensible deed and at the top of the ladder there is an image of the child enjoying the reward. At the top of the chutes, there are pictures of children engaging in mischievous or foolish behaviour and the images on the bottom show the child suffering the consequences. There have also been many pop culture versions of the game produced in recent years, with graphics featuring such characters as Dora the Explorer and SpongeBob SquarePants.

In Canada the game has been traditionally sold as Snakes and Ladders, and produced by the Canada Games Company. Several Canadian specific versions have been produced over the years, including version substituting Toboggan runs for the snakes.[5] With the demise of the Canada Games Company, Chutes and Ladders produced by Milton Bradley/Hasbro has been gaining in popularity.

The most common[citation needed] in the United Kingdom is Spear's Games' edition of Snakes and Ladders, played on a 10×10 board where a single die is used.

During the early 1990s in South Africa, Chutes and Ladders games made from cardboard were distributed on the back of egg boxes as part of a promotion.[citation needed]

Mathematics of the game

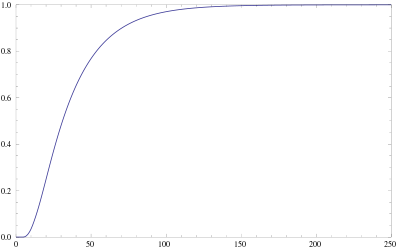

Any version of Snakes and Ladders can be represented exactly as a Markov chain, since from any square the odds of moving to any other square are fixed and independent of any previous game history. The Milton Bradley version of Chutes and Ladders has 100 squares, with 19 chutes and ladders. A player will need an average of 39.6 spins to move from the starting point, which is off the board, to square 100.

In the book Winning Ways the authors show how to treat Snakes and Ladders as an impartial game in combinatorial game theory even though it is very far from a natural fit to this category. To this end they make a few rule changes such as allowing players to move any counter any number of spaces, and declaring the winner as the player who gets the last counter home. This version, which they call Adders-and-Ladders, involves more skill than the original game.

In culture

The game is a central metaphor of Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children. The narrator describes the game thusly:

All games have morals; and the game of Snakes and Ladders captures, as no other activity can hope to do, the eternal truth that for every ladder you hope to climb, a snake is waiting just around the corner, and for every snake a ladder will compensate. But it's more than that; no mere carrot-and-stick affair; because implicit in the game is unchanging twoness of things, the duality of up against down, good against evil; the solid rationality of ladders balances the occult sinuosities of the serpent; in the opposition of staircase and cobra we can see, metaphorically, all conceivable oppositions, Alpha against Omega, father against mother.[6]

Notes

- ^ About.com – Chutes and Ladders

- ^ a b S. C. Althoen, L. King, K. Schilling (March 1993). "How Long Is a Game of Snakes and Ladders?". The Mathematical Gazette (The Mathematical Gazette, Vol. 77, No. 478) 78 (478): 71–76. doi:10.2307/3619261. JSTOR 3619261.

- ^ a b Augustyn, pages 27–28

- ^ http://devdutt.com/playing-with-fate-and-free-will

- ^ ELLIOTT AVEDON MUSEUM & ARCHIVE OF GAMES – Snakes and Ladders

- ^ Salman Rushdie. Midnight's Children. Random House Trade Paperback Edition, 2006. pg. 160

References

- Augustyn, Frederick J. (2004). Dictionary of toys and games in American popular culture. Haworth Press. ISBN 0789015048.

- Tatz, Mark / Kent, Jody (1977). Rebirth. The Tibetan Game of Liberation. Anchor Press 1977. ISBN 0385114214

External links

- Hasbro's official Chutes and Ladders page

- Mathematical analysis of Chutes and Ladders

- Perl software to generate statistics for Chutes and Ladders

- Snakes and Ladders at BoardGameGeek

- Jain version of Snakes and Ladders explained in an interactive demonstration hosted by the Victoria and Albert Museum

- Leela, the Game of Knowledge Hindu version

- Shatranj Irfani Indian Sufi version XIX century

Categories:- Children's board games

- Roll-and-move board games

- Race games

- Markov models

- 1943 introductions

- Indian inventions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.