- Max Delbrück

-

Max Delbrück

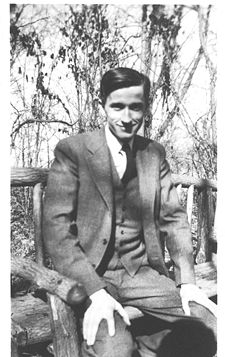

Delbrück in the early 1940s.Born September 4, 1906

Berlin, German EmpireDied March 9, 1981 (aged 74)

Pasadena, California, United StatesFields Biophysics Known for Phage group Notable awards Nobel laureate Max Ludwig Henning Delbrück (September 4, 1906 – March 9, 1981) was a German-American biophysicist and Nobel laureate.

Contents

Biography

Delbrück was born in Berlin, German Empire. His father was Hans Delbrück, a professor of history at the University of Berlin, and his mother was the granddaughter of Justus von Liebig.

Delbrück studied astrophysics, shifting towards theoretical physics, at the University of Göttingen. After receiving his Ph.D. in 1930, he traveled through England, Denmark, and Switzerland. He met Wolfgang Pauli and Niels Bohr, who got him interested in biology.

Delbrück went back to Berlin in 1932 as an assistant to Lise Meitner, who was collaborating with Otto Hahn on the results of irradiating uranium with neutrons. During this period he wrote a few papers, one of which turned out to be an important contribution on the scattering of gamma rays by a Coulomb field due to polarization of the vacuum produced by that field (1933). His conclusion proved to be theoretically sound but inapplicable to the case in point, but 20 years later Hans Bethe confirmed the phenomenon and named it "Delbrück scattering".[1]

In 1937, he moved to the United States to pursue his interests in biology, taking up research in the Biology Division at Caltech on genetics of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. While at Caltech Delbrück became acquainted with bacteria and their viruses (bacteriophage or 'phage'). In 1939, he co-authored a paper called The Growth of Bacteriophage with E.L. Ellis in which they demonstrated that viruses reproduce in "one step", rather than exponentially as cellular organisms do.

In 1941, he married Mary Bruce, with whom he had four children. Delbrück's brother Justus Delbrück, a lawyer, his sister Emmi Bonhoeffer and his brothers-in-law Klaus Bonhoeffer and Dietrich Bonhoeffer) were heroes in the German Resistance against the Nazi Regime. Klaus and Dietrich Bonhoeffer were executed in the last days of Hitler's Germany.

Delbrück remained in the US during World War II, teaching physics at Vanderbilt University in Nashville while pursuing his genetic research. In 1942, he and Salvador Luria of Indiana University demonstrated that bacterial resistance to virus infection is caused by random mutation and not adaptive change. This research, known as the Luria-Delbrück experiment, was also significant for its use of mathematics to make quantitative predictions for the results to be expected from alternative models. For that work, they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1969, sharing it with Alfred Hershey.[2] In the same year together with Salvador Luria he was awarded the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University.

In 1947, Delbrück returned to Caltech as a professor of biology where he remained until 1977.

From the 1950s on, Delbrück applied biophysical methods to problems in sensory physiology rather than genetics. He also set up the institute for molecular genetics at the University of Cologne.

Dr. Max Delbrück, one of the foremost pioneers of modern molecular genetics, died on the evening of Monday, March 9, 1981, at the Huntington Memorial Hospital, Pasadena, California, at the age of 74. At that time, he was the Board of Trustees Professor of Biology emeritus at the California Institute of Technology. Delbrück was one of the most influential people in the movement of physical scientists into biology during the 20th century. Delbrück's thinking about the physical basis of life stimulated Erwin Schrödinger to write the highly influential book, What Is Life?.[3] Schrödinger's book was an important influence on Francis Crick, James D. Watson and Maurice Wilkins who won a Nobel prize for the discovery of the DNA double helix.[4] Beginning in 1945 Delbrück developed a course in bacteriophage genetics at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory to encourage interest in the field. Delbrück's efforts to promote the "Phage Group" (exploring genetics by way of the viruses that infect bacteria) was important in the early development of molecular biology.[5] On 26–27 August 2006, what would have been his 100th birthday celebration, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory hosted a meeting of Delbrück's family members and friends to reminisce about the life and work of Delbrück.[6]

See also

- Luria-Delbrück experiment

- Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize

- Max Delbruck Prize, formally known as the biological physics prize, awarded by the American Physical Society

- Saffman–Delbrück model

References

- ^ Biographical Memoirs: Volume 62 pp66-117 "MAX LUDWIG HENNING DELBRÜCK 4 September 1906 – 10 March 1981" BY WILLIAM HAYES http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=2201&page=66

- ^ Lagemann, Robert T. "Max Delbrück at Vanderbilt" in To Quarks and Quasars, A History of Physics and Astronomy at Vanderbilt University, 2000. pp. 165-193.

- ^ See: "Erwin Schrödinger and the Origins of Molecular Biology" by Krishna R. Dronamrajua in Genetics (1999) Volume 153 page 1071-1076. full text

- ^ Schrödinger's influence and role in the discovery of the structure of DNA is described by Horace Freeland Judson in The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Biology published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press (1996) ISBN 0879694785.

- ^ Watson, J.D. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. 2010.

- ^ Haslinger, Kiryn. Max Delbruck 100. HT Winter 2007.

- Ton van Helvoort (1992). "The controversy between John H. Northrop and Max Delbrück on the formation of bacteriophage: Bacterial synthesis or autonomous multiplication?". Annals of Science 49 (6): 545–575. doi:10.1080/00033799200200451. PMID 11616207.

- Lily E. Kay (1985). "Conceptual models and analytical tools: The biology of physicist Max Delbrück". Journal of the History of Biology 18 (2): 207–246. doi:10.1007/BF00120110. PMID 11611706.

- Daniel J. McKaughan (2005). "The Influence of Niels Bohr on Max Delbrück". Isis 96 (4): 507–529. doi:10.1086/498591. PMID 16536153.

External links

- Nobel prize webpage

- Delbrück page at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory website.

- Letter from Jim Watson – Delbrück was instrumental in getting fellowship support for Watson so that he could stay in Cambridge, play tennis, and discover the rules of nucleotide base pairing in DNA. This is a letter from Watson to Delbrück that describes the discovery.

- Interview with Max Delbrück Oral History Project, California Institute of Technology Archives, Pasadena, California.

- Caltech Photo Archives of Max Delbrück

- The Official Site of Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize

- Key Participants: Max Delbrück – Linus Pauling and the Race for DNA: A Documentary History

Categories:- 1906 births

- 1981 deaths

- People from Berlin

- Biophysicists

- American Nobel laureates

- German emigrants to the United States

- German scientists

- American people of German descent

- German Nobel laureates

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- Phage workers

- University of Göttingen alumni

- Vanderbilt University faculty

- California Institute of Technology faculty

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society

- Molecular biologists

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.