- Silat Melayu

-

This article is about silat styles from the Malay Peninsula. For the general article, see Silat.

Silat Melayu (Jawi: سيلت ملايو; lit. "Malay silat") is a blanket term for the types of silat created in peninsular Southeast Asia, particularly Malaysia, Thailand, Brunei and Singapore. The silat tradition has deep roots in Malay culture and can trace its origin to the dawn of Malay civilization, 2000 years ago.[1][2][3][4] Since the classical age, silat Melayu underwent great diversification and formed what is today traditionally recognized as the source of Indonesian pencak silat.[5][6] Nowadays, the term silat Melayu is most often used to differentiate the Malay styles from Indonesian pencak silat.

Contents

Etymology

The etymological root of the word silat is uncertain and most hypotheses link it to any similar-sounding word. It may come from Si Elat which means someone who confuses, deceives or bluffs. A similar term, ilat, means an accident, misfortune or a calamity.[7] Another theory is that it comes from silap meaning wrong or error. Some styles contain a set of techniques called Langkah Silap designed to lead the opponent into making a mistake.

The word Melayu means Malay and came from the Sanskrit term Malaiur or Malayadvipa which can be translated as “mountain insular continent”, the word used by ancient Indian traders when referring to the Malay Peninsula.[8][9][10][11][12] Silat is sometimes called gayung or gayong in the northern Malay Peninsula. In other regions the word gayung refers to the spiritual practices in silat. Silat Melayu is sometimes mistakenly called bersilat but this is actually a verbal form of the noun silat.

History

Origins

The first martial skills in the Malay Peninsula were those of the indigenous tribes (orang asli) who would use hunting implements like spears, machetes, blowpipes and bows and arrows in raids against enemy tribes. Certain tribes were well-known warriors and pirates such as the Iban and the Tringgus of Borneo. Aboriginal populations on the peninsula were mostly replaced by Deutero-Malays and Chamic people in a wave of migration from mainland Asia around 300 B.C.[13][14] These settlers were rice-farmers from whom modern Malays are directly descended. The areas from where they originated are concurrent with the early evidence of silat.

Early kingdoms

The Malays had already established regular contact with both India and China before the 1st century. Silat was largely shaped by Chinese and Indian martial arts, as evidenced by Kedah's 2nd-century Bujang Valley civilisation which housed various Indian weapons including an ornate trisula. The local adoption of the Indian religions of Hinduism and Buddhism resulted in the founding of early Malay kingdoms throughout the region, notably Langkasuka (1st century), Gangga Negara (2nd century), and the Kedah Kingdom (7th century).

From these ancient Malay city-states, the earliest forms of silat Melayu were developed and eventually used in the armed forces to defend the land.[1][15] Tradition credits silat tua (lit. "old silat") as the first system of silat Melayu to have been founded on the peninsula. The area from Isthmus of Kra to the northern Malay peninsula, a border area between Malaysia and Thailand where it was created, is culturally significant and considered to be the "cradle of Malay civilization and culture".[16][17]

Gangga Negara, one of the peninsula's oldest kingdoms, was eventually destroyed by Rajendra Chola I of the Tamil Chola empire. Today, most Malaysian Indians are Tamils, who influenced several Southeast Asian martial arts through silambam. This staff-based fighting style was already being practiced by the region's Indian community when Malacca Sultanate was founded at the beginning of the 15th century. During the 18th century silambam became more prevalent in the Malay Peninsula than in India, where it was banned by the British government.[18] The bamboo staff is still one of silat's most fundamental weapons.

The seventh century was the beginning of the Srivijaya civilization in Palembang, Sumatra and the influence of silat from the mainland Malay society was consolidated by Ninik Dato' Suri Diraja (1097–1198) to create silek (Minang silat) of Sumatra.[15]

Champa

The Cham people are an ethnic group of Malayo-Polynesian stock originating in present-day Vietnam and Cambodia. They are believed by many archaeologists to have created the prototype of a kris as far back as 2000 years ago.[15] The Chams established the kingdom of Champa in an area that constitutes today’s southern Vietnam around the first century A.D. The kingdom remained independent from the Chinese who controlled Vietnam's north and in its refusal to submit, Champa frequently waged wars against China[1] as well as other neighboring kingdoms, Đại Việt and Khmer Empire.

As a result of their experience in wars, commanders of Champa are known to have been held in high esteem by the Malay kings for their knowledge in silat and for being highly skilled in the art of war, as mentioned in the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals). It is said that Sultan Muhammad Shah had chosen a Cham official as his right hand or senior officer because the Chams possessed skill and knowledge in the administration of the kingdom.[19]

Legend

A Malaysian variant of an Indonesian story explains that the first complete system of silat was created by a woman who was carrying a basket of food on her head when birds tried to steal the food from her. She dodged the birds coming from all directions while at the same time balancing the basket on her head and attempting to chase the birds away with her hands. She arrived home late and was scolded by her husband who had no food to eat. He tried to beat the woman but she avoided all his attacks and was completely untouched. Her husband had grown tired and after listening to her explanation for being late, asked his wife to teach him what she had learned. Together they created the rudiments of silat.

Sultanate era

The Islamic faith first arrived in the shores of what are now the states of Kedah, Perak, Kelantan and Terengganu, beginning in the 12th century.[20] This event was subsequently followed by the emergence of powerful Malay sultanates like the Kedah Sultanate (1136), Brunei Sultanate (1363), Malacca Sultanate (1402) and Pattani Kingdom (1516), that dominated the western Malay archipelago and northern Borneo.

From the 13th-16th century, many Malay traditions including silat and the Malay language were disseminated throughout the entire archipelago. The Malay sultanates became the center of Malay cultural expressions and silat was further refined into the specialized property of the nobility, pendekar, and panglima (governor-generals). Kings encouraged princes and children of dignitaries to learn silat and any other form of knowledge related to the necessities of combat. Upper-class nobles would often send their children to study abroad in India or China. Prominent fighters were elevated to head war troops and received ranks or bestowals from the raja.[1] The most famous of these was the Melakan admiral Hang Tuah. He learned martial arts together with his four compatriates - Hang Jebat, Hang Lekir, Hang Kasturi and Hang Lekiu - from two of the most renowned silat guru of the era. In Malaysia today, Hang Tuah is called the "father of silat"[21] which has led to the misconception that he created silat. However, Hang Tuah is more likely to have been one of the art's disseminators rather than its originator[22] since silat is known to have been practiced long before the founding of Melaka.

Colonial and modern era

In the 16th century, conquistadors from Portugal attacked Melaka in an attempt to monopolize the spice trade. The Malay warriors managed to hold back the better-equipped Europeans for over 40 days before Malacca was eventually defeated. The Portuguese hunted and killed anyone with knowledge of martial arts so that the remaining practitioners fled to more isolated areas.[23] Even today, the best silat masters are said to come from rural villages that have had the least contact with outsiders.

For the next few hundred years, the Malay Archipelago would be contested by a string of foreign rulers, namely the Portuguese, Dutch, and finally the British. The 17th century saw an influx of Minangkabau and Bugis people into Malaya from Sumatra and south Sulawesi respectively. Bugis sailors were particularly famous for their martial prowess and were feared even by the European colonists. Between 1666 and 1673, Bugis mercenaries were employed by the Johor empire when a civil war erupted with Jambi, an event that marked the beginning of Bugis influences in local conflicts for succeeding centuries. By the 1780s the Bugis had control of Johor and established a kingdom in Selangor. With the consent of the Johor ruler, the Minangkabau formed their own federation of nine states called Negeri Sembilan in the hinterland. Today, some of Malaysia's silat schools can trace their lineage directly back to the Minang and Bugis settlers of this period.

After Malaysia achieved independence, Tuan Haji Anuar bin Haji Abd. Wahab was given the responsibility of developing the nation's national silat curriculum which would be taught to secondary and primary school students all over the country. On 28 March 2002, his Seni Silat Malaysia was recognised by the Ministry of Heritage and Culture, the Ministry of Education and PESAKA as Malaysia's national silat. Since its disassociation with the palace, silat did not develop in the national defence institution and returned to the countryside. It is now conveyed to the community by means of the gelanggang bangsal meaning the martial arts training institution carried out by silat instructors.[24]

Uniform

Silat attire varies according to style and locality. People of the Malay Peninsula traditionally wore sarong and carried a roll of cloth which could be used as a bag, a blanket or a weapon. The standard full dress of today's silat practitioners usually consists of the following:

- The tengkolok and tanjak are headkerchiefs with different ways of tying them depending on status and region.

- The baju Melayu, meaning "Malay clothes" is the male shirt but is also worn by female silat exponents.

- The samping is a waistcloth.

- The bengkung is a cloth belt or sash which secures the samping. Some schools colour the bengkung to signify rank, a practice adopted from the belt system of Japanese martial arts.

Training hall

In Malay the practice area is called a gelanggang. They were traditionally located outdoors, either in a specially constructed part of the village or in a jungle clearing. The area would be enclosed by a fence made of bamboo and covered in nipah or coconut leaves to prevent outsiders from stealing secrets. Before training can begin, the gelanggang must be prepared either by the teachers or senior students in a ritual called "opening the training area" (buka gelanggang ). This starts by cutting some limes into water and then walking around the area while sprinkling the water onto the floor. The guru walks in a pattern starting from the centre to the front-right corner, and then across to the front-left corner. She/he then walks backwards past the centre into the rear-right corner, across to the rear-left corner, and finally ends back in the centre. The purpose of walking backwards is to show respect to the gelanggang, and any guests that may be present, by never turning one's back to the front of the area. Once this has been done, the teacher sits in the centre and recites an invocation so the space is protected with positive energy. From the centre, the guru walks to the front-right corner and repeats the invocation while keeping his/her head bowed and hands crossed. The right hand is crossed over the left and they are kept at waist level. The mantera is repeated at each corner and in the same pattern as when the water was sprinkled. As a sign of humility, the guru maintains a bent posture while walking across the training area. After repeating the invocation in the centre once more, the teacher sits down and meditates. Although most practitioners today train in modern indoor gelanggang and the invocations are often replaced with a prayer, this ritual is still carried out in some form or another.

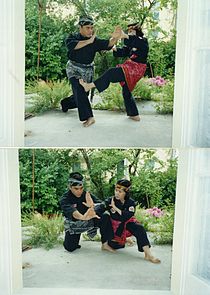

Silat Pulut

Silat pulut is a sport that utilizes agility in attacking and defending oneself.[25] In this exercise, the two partners begin some distance apart and perform freestyle movements while trying to match the each other's flow. One attacks when they notice an opening in the opponent's defences. Without interfering with the direction of force, the defender then parries and counterattacks. The other partner follows by parrying and attacking. This would go on with both partners disabling and counter-attacking their opponent with locking, grappling and other techniques. Contact between the partners is generally kept light but faster and stronger attacks may be agreed upon beforehand. In another variation which is also found in chin na, the initial attack is parried and then the defender applies a lock on the attacker. The attacker follows the flow of the lock and escapes it while putting a lock on the opponent. Both partners go from lock to lock until one is incapable of escaping or countering.

This game is called silat pulut or gayong pulut because after a performance each player is gifted with bunga telur and sticky rice or pulut. Silat pulut is held during leisure time, the completion of silat instruction, official events, weddings or festivals where it is accompanied by the rhythm of gendang silat (silat drums) or tanji silat baku (traditional silat music).[26] As with a tomoi match, the speed of the music adapts to the performer's pace.

British colonists introduced western training systems by incorporating the police and sepoys (soldiers who were local citizens) to handle the nation's defence forces which at that time were receiving opposition from former Malay fighters. Consequently, silat teachers were very cautious in letting their art become apparent because the colonists had experience in fighting Malay warriors.[26] Thus silat pulut provided an avenue for exponents to hone their skills without giving themselves away. It could also be used as preliminary training before students are allowed to spar, somewhat like Keralan adithada.

Despite its satirical appearance, silat pulut actually enables students to learn moves and their applications without having to be taught set techniques. Partners who frequently practice together can exchange hard blows without injuring each other by adhering to the principle of not meeting force with force. What starts off as a matching of striking movements is usually followed by successions of locks and may end in groundwork, a pattern that is echoed in the modern Mixed Martial Arts.

Weapons

Weapons of silat Weapon Definition Kris A dagger which is often given a distinct wavy blade by folding different types of metal together and then washing it in acid. Parang Machete/ broadsword, commonly used in daily tasks such as cutting through forest growth. Golok Tombak Spear/ javelin, made of wood, steel or bamboo that may have dyed horsehair near the blade. Lembing Tongkat Staff or walking stick made of bamboo, steel or wood. Batang Gedak A mace or club usually made of iron. Kipas Folding fan preferably made of hardwood or iron. Kerambit A concealable claw-like curved blade that can be tied in a woman's hair. Sabit Sickle commonly used in farming, harvesting and cultivation of crops. Serampang Trident originally used for fishing. Trisula Tekpi Three-pronged truncheon thought to derive from the trident. Chabang Chindai Wearable sarong used to lock or defend attacks from bladed weapons. Samping Rantai Chain used for whipping and seizing techniques See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Thesis: Seni Silat Melayu by Abd Rahman Ismail (USM 2005 matter 188)

- ^ James Alexander (2006). Malaysia Brunei & Singapore. New Holland Publishers. pp. 225, 51, 52. ISBN 1-86011-309-5.

- ^ Abd. Rahman Ismail (2008). Seni Silat Melayu: Sejarah, Perkembangan dan Budaya. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. p. 188. ISBN 9789836299345.

- ^ Black Belt. Rainbow Publications. October Edition, 1994. pp. 73. ISBN 0277-3066.

- ^ Donn F. Draeger (1992). Weapons and fighting arts of Indonesia. Tuttle Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 0804817162.

- ^ D. S. Farrer (2009). Shadows of the Prophet: Martial Arts and Sufi Mysticism. Springer. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4020-9355-5).

- ^ Silat Dinobatkan Seni Beladiri Terbaik by Pendita Anuar Abd. Wahab AMN (pg. 42 SENI BELADIRI June 2007, no: 15(119) P 14369/10/2007)

- ^ Govind Chandra Pande (2005). India's Interaction with Southeast Asia: History of Science,Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Vol. 1, Part 3. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 266. ISBN 978-8187586241.

- ^ Lallanji Gopal (2000). The economic life of northern India: c. A.D. 700-1200. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 139. ISBN 9788120803022.

- ^ D.C. Ahir (1995). A Panorama of Indian Buddhism: Selections from the Maha Bodhi journal, 1892-1992. Sri Satguru Publications. p. 612. ISBN 8170304628.

- ^ Radhakamal Mukerjee (1984). The culture and art of India. Coronet Books Inc. p. 212. ISBN 9788121501149.

- ^ Himansu Bhusan Sarkar (1970). Some contributions of India to the ancient civilisation of Indonesia and Malaysia. Calcutta: Punthi Pustak. p. 8.

- ^ Alan Collins (2003). Security and Southeast Asia: domestic, regional, and global issues. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 26. ISBN 981-230-230-1.

- ^ "The Malays". Sabrizain.org. http://www.sabrizain.org/malaya/malays.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- ^ a b c Guru Nizam. "Silat History: The Origin Of Silat". www.articlesbase.com. http://www.articlesbase.com/martial-arts-articles/silat-history-the-origin-of-silat-2802648.html. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Keat Gin Ooi (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, From Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. p. 927. ISBN 979-1576077701.

- ^ "Rivers deep or mountains high?". Sabrizain.org. http://www.sabrizain.org/malaya/malays4.htm. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Crego, Robert (2003). Sports and Games of the 18th and 19th Centuries pg 32. Greenwood Press

- ^ Sejarah Melayu by A. Samad Ahmad 1996: matter 75

- ^ Hussin Mutalib (2008). Islam in Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 25. ISBN 978-981-230-758-3.

- ^ Sheikh Shamsuddin (2005). The Malay Art Of Self-defense: Silat Seni Gayong. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 1556435622.

- ^ Donn F. Draeger and Robert W. Smith (1969). Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts. ISBN 978-0-87011-436-6.

- ^ Zainal Abidin Shaikh Awab and Nigel Sutton (2006). Silat Tua: The Malay Dance Of Life. Kuala Lumpur: Azlan Ghanie Sdn Bhd. ISBN 9789834232801.

- ^ Martabat Silat Warisan Negara, Keaslian Budaya Membina Bangsa PESAKA (2006) [Sejarah Silat Melayu by Tn. Hj. Anuar Abd. Wahab]

- ^ Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Dictionary (Teuku Iskandar 1970)

- ^ a b Martabat Silat Warisan Negara, Keaslian Budaya Membina Bangsa PESAKA (2006) [Istilah Silat by Anuar Abd. Wahab]

Notations

- Sejarah Silat Melayu by Anuar Abd. Wahab (2006) in PESAKA (2006).

- Istilah Silat by Anuar Abd. Wahab (2006) in PESAKA (2006).

- Silat Dinobatkan Seni Beladiri Terbaik by Pendita Anuar Abd. Wahab AMN (2007) in SENI BELADIRI (June 2007)

- Silat itu Satu & Sempurna by Pendita Anuar Abd. Wahab AMN (2007) in SENI BELADIRI (September 2007)

Further reading

- Donn F. Draeger and Robert W. Smith (1980). Comprehensive Asian fighting arts. Kodansha International. ISBN 9780870114366.

External links

- Silat Melayu Main Silat Melayu school in Malaysia.

- Silat Melayu Book History and Development of Silat in Malaysia.

- Silat Melayu News Martial Arts Community Malaysia

- Video Silat Silat Melayu Training Course Online

- Silat Melayu Training Centre Top Silat Melayu Training Centre in Malaysia

Categories:- Silat

- Malay culture

- Malaysian culture

- Singaporean culture

- Sport in Malaysia

- Sport in Singapore

- Sport in Brunei

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.