- Orienteering map

-

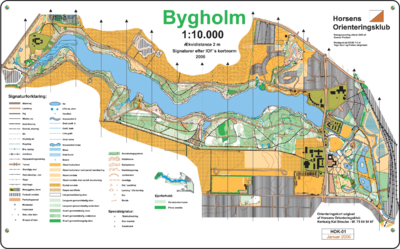

An orienteering map is a map specially prepared for use in orienteering competitions. It is a topographic map with extra details to help the competitor navigate through the competition area.

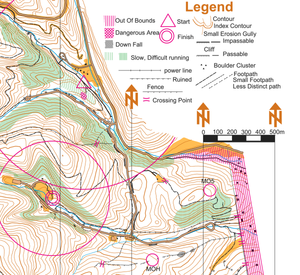

These maps are much more detailed than general-purpose topographic maps, and incorporate a standard symbology that is designed to be useful to anyone, regardless of native language. In addition to indicating the topography of the terrain with contour lines, orienteering maps also show forest density, water features, clearings, trails and roads, earthen banks and rock walls, ditches, wells and pits, fences and power lines, buildings, boulders, and other features of the terrain. Orienteering maps are 1:15 000 or 1:10 000 scale.[1]

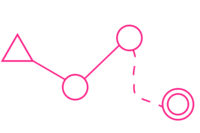

Orienteering map (not to IOF standard) marked for amateur radio direction finding, with a triangle at Start, large and small concentric circles at Finish, and two of five control points (hidden radio beacons). Beacon control points are shown for post-competition analysis; ARDF competitors must find the beacons.

Orienteering map (not to IOF standard) marked for amateur radio direction finding, with a triangle at Start, large and small concentric circles at Finish, and two of five control points (hidden radio beacons). Beacon control points are shown for post-competition analysis; ARDF competitors must find the beacons.

Contents

Purpose

An orienteering map, and a compass, are the primary aids for the competitor to complete an orienteering course of control points as quickly as possible.[2] A map that is reliable and accurate is essential so that a course can be provided which will test the navigational skills of the competitor. The map also needs to be relevant to the needs of the competitor showing the terrain in neither too much nor too little detail.

Because the competition must test the navigational skills of the competitor, areas are sought which have a terrain that is rich in usable features. In addition, the area should be attractive and interesting. Notable examples in the US include Pawtuckaway State Park, New Hampshire and Valles Caldera, New Mexico, both having many boulders and boulder fields, and a wide variety of other terrain types.

Orienteering maps are produced by local orienteering clubs and are a valuable resource for the club. Orienteering maps are expensive to produce and the principal costs are: the fieldwork, drawing (cartography), and printing. Each of these can use up valuable resources of a club, be it in manpower or financial costs. Established clubs with good resources e.g. maps and manpower are usually able to host more events.

History

In the early days of orienteering, competitors used whatever maps were available; these were typically topographic maps from the national mapping agency. While national mapping agencies update their topographic maps on a regular basis, they are usually not sufficiently up to date for orienteering purposes. Gradually, specially drawn maps have been provided to meet the specific requirements of orienteering.

Maps produced specifically for orienteering show a more detailed and up-to-date description of terrain features. For example, large rocks above the soil surface do not normally appear on topographic maps but can be important features on many orienteering maps. New features such as fence lines can be important navigational aids and may also affect route choice. Orienteering maps include these new features.

Cartographer Jan Martin Larsen was a pioneer in the development of the specialized orienteering map.

Map content

The map scale is 1:15 000, with a permitted enlargement to 1:10 000 (with symbols at 150%). Other map scales may be provided for various purposes, for example Sprint maps use a scale of 1:5 000 or 1:4 000. The map is printed in five colours,[2] which cover the main groups: Land forms, rock and boulders, water and marsh, vegetation, and man-made features. There are additional specifications for technical symbols, and an extra colour for overprinting symbols. The symbols used should be explained in a legend.[2]

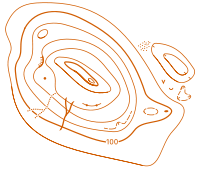

Brown: Land forms

Land forms are shown using contour lines with a contour interval of 5 metres. Additional symbols are provided to show e.g. earth bank, knoll, depression, small depression, pit, broken ground etc.

Black: Rock features

This group covers cliffs, boulders, boulder fields, and boulder clusters etc.

Blue: Water features

This group covers lakes, ponds, rivers, water channels, marshes, and wells etc.

Green/Yellow: Vegetation

This group covers vegetation. White is typically open runnable forest. Green means a forest of low visibility with reduced running speed, being graded from slow running, through difficult running, to impassable. Yellow colour shows open areas. Green vertical stripes are used to indicate undergrowth (slow or difficult running) but otherwise with good visibility.

Black: Man-made features

Man-made features include roads, tracks, paths, power lines, stone walls, fences, buildings, etc.

Technical symbols

Two technical symbols are required on all maps: Magnetic north lines printed in blue, and register crosses (these show that the printed colours are coincident).[2]

Other map information

Other information is required to be on the printed map although the presentation is not specified, e.g. scale, contour interval and scale bar. Good practice requires information such as date of survey, survey scale, copyright information, and proper credit for the people who produced the map (surveyor, cartographer).

Purple: Overprinting symbols

Symbols are specified so that a course can be overprinted on the map. It includes symbols for the start, control points, control numbers, lines between control points, and finish. Extra symbols are available so that information relating to that event may be shown e.g. crossing points, forbidden route, first aid post, and refreshment point etc. These are not permanent features and cannot be included when the map is printed.

Related activities

The International Specification for Orienteering Maps[2] sets out the specifications for orienteering maps for use in foot orienteering, together with specifications for the other sports governed by the International Orienteering Federation (IOF) i.e. mountain bike orienteering, ski orienteering, and trail orienteering. The specifications are mostly the same but with a few sport specific symbols e.g. ski-o needs to distinguish snow-covered roads from cleared roads.

Mapping process

The mapping process has four main stages: Creation of the base map, field-work, drawing, and printing.

Base map

The base map can be a topographic map made for other purposes e.g. mapping from the National Mapping Agency, or a photogrammetric plot produced from an aerial survey.

As LIDAR-surveying advances, base maps consisting of 1 meter contours and other data derived from the LIDAR data get more common. As these base maps contain large amounts of information the cartographic generalization becomes important in creating a readable map.[3]

Magnetic north

Cartographers use a projection to project the curved surface of the earth onto a flat surface. This generates a grid that is used as a base for national topographic mapping. The projection introduces a distortion so that grid north differs from true north; magnetic north is a natural feature that differs from both. As an example: at 52° 35' N 1° 10' E (approx 7 km west of Norwich, England) true north is 2° 33' west of grid north, and magnetic north is about 7° west of grid north. Magnetic north varies continually and in this example (1986) was reducing by about ½° in four years.[4] Orienteering maps are printed using magnetic north and this requires an adjustment to be made to the base map.

Field-work

Field-work is carried out using a small part of the base map fixed to a survey board, covered with a piece of draughting film, and drawn with pencils. The final map needs to be drawn with sufficient accuracy so that a feature shown on the map can be identified clearly on the ground by the competitor, thus, field-workers need to locate features with a high level of accuracy, to ensure consistency between map and terrain. Where the map and terrain are inconsistent, the feature becomes unusable: no control point can be placed there. Periodic corrections to the map may be necessary, typically vegetation changes in forested areas.

Drawing (cartography)

Corrected topographic maps

The earliest orienteering maps used existing topographic maps e.g. United Kingdom Ordnance Survey 1:25 000 plans. These were cut down to a suitable size, corrected by hand, and then copied.

Hand-drawn orienteering maps

Hand-drawn maps

These were initially drawn by hand on tracing paper using one sheet for each of the five colours; the various dot or line screens being added using dry transfer screens, for example Letratone manufactured by Letraset in the UK. The map was drawn at twice final map scale, and photographically reduced to produce the five film positives for printing. This was a simple process that required very few specialist tools. Draughting film has replaced tracing paper. This is a plastic waterproof material etched on one side so that the ink will hold.

Scribed maps

This is the standard process used by National Mapping Agencies. It uses a plastic film, which is coated on one side with a photo-opaque film. The layer is removed with a scribing tool or scalpel to produce a negative image. One sheet of film is needed for each solid colour, and one for each screen, usually requiring about ten sheets of film altogether. The map is drawn at final map scale, and the negatives are printed with high quality dot screens to produce the five film positives for printing. The process makes it easy to produce high quality maps, but it does require a number of specialist tools.

Computer aided maps (digital cartography)

Computer software is available to aid in the drawing of digital maps. OCAD is the leading provider. Other computer software is available that will link with OCAD, or with the digital map files, so that courses can be incorporated into the map ready for printing.

Printing

Colour maps were sent to commercial printers for printing in five colours, with the overprinting being added after the map had been printed. This process was chosen as it gave a higher quality for the fine line-work than the industry standard four-colour process (CMYK). As computer and software technology has advanced, and the cost reduced, many clubs are now in a position to print their own maps. This enables clubs to print the six colours together (map and overprinting symbols) using that same four-colour process, but with a reduction in quality over traditional printing. Printing costs can be minimised by using standard stock sizes of paper e.g. A4 or Letter. It is important to use the correct type of paper: both the weight and the coating affect the usability of the final map.

Map accuracy and map quality

Map accuracy refers to the work of the surveyor (field-worker) and relates not so much to the positional accuracy of the survey but rather to its utility for the competitor. Map quality refers to the quality of the artwork. Many national bodies have a competition in which awards are made to cartographers after assessment by a national panel. It is generally agreed by cartographers that the quality of the artwork depends on the skills of the cartographer rather than on the tools.[5]

References

- ^ Zentai, László, ed. (2000). International Drawing Specifications for Orienteering Maps (ISOM2000). International Orienteering Federation.

- ^ a b c d e "International Specification for Orienteering Maps". International Orienteering Federation. 2000. http://www.orienteering.org/i3/index.php?/iof2006/content/download/866/4026/file/International_Specification_for_Orienteering_Maps_2000.pdf. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ^ Turka, Janeta (2010). Using Laserscanning in Latvia . 14th International Conference on Orienteering Mapping.

- ^ [United Kingdom] Ordnance Survey, 1:50 000 Landranger Series, sheet 144, 1984

- ^ Proverb. A bad workman blames his tools.

External links

Orienteering History Orienteering concepts Sport disciplinesIOF governedIARU governedOther sportsRelated sportsEquipmentEventPersonalExceptionsFundamentalsMap (Orienteering map) · Navigation (Resection, Route choice, Wayfinding, Waypoint) · Racing (Hiking, Running, Walking)OrganizationNon-sport relatedAdventure travel · Bicycle touring · Location-based game (Geocaching, Poker run) · Hiking · Hunting · Mountaineering · Scoutcraft orienteering · Traveling backpacking · Wilderness backpackingOrienteering competition events Top ranked onlyOpen to everyoneTop ranked onlyTop ranked onlyWorld ChampionshipsOpen to everyoneList of orienteering events Browse orienteering articles by category Categories:- Orienteering

- Map types

- Sports equipment

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.