- Onryō

-

Onryō (怨霊) is a mythological spirit from Japanese folklore who is able to return to the physical world in order to seek vengeance.

While male onryō can be found, mainly in kabuki, the majority are women. Powerless in the physical world, they often suffer at the capricious whims of their male lovers. In death they become strong.

Contents

Origin of onryō

While origin of onryō is uncertain, this notion could be back to the 8th Century at least (see below) and was based on the notion powerful and raged souls of the dead could give bad influence in the land of the living.

The traditional Japanese spirit world is consisted with two layers: the world of living and the other of the dead. Regardless who he was before death, all go to Yomi, if died. It means that even kami (deities) died from several causes and then they should move to the land of the dead. While it is impossible for the dead to come back to the world of the living anymore according to Japanese mythology, still the dead spirits could voluntarily give an influences on the living either mercifully or malignantly. Kojiki (711-2), the oldest Japanese book which narrates Japanese history beginning from its mythology, tells the died goddess Izanami cast a curse from Yomi to the land of living. Although died kami could be so malignant as the above, onryō refers specifically to the died human souls in malice, causing actual harms. The earliest remaining record of onryō is found in Shoku Nihongi (797): a high ranked courtier Fujiwara no Hirotsugu (died in 740 ja:藤原広嗣), who lost his power and defeated in a failed rebel against Genbō is mentioned after his death as "Hirotsugu's soul harmed Genbō to death".[1]

Onryō vengeance

Onryō were believed to be driven by their desire for vengeance, as the example of Hirotsugu against Genbō. Appearance of their revenges were however believed vary from their former enemies' misfortune to natural disasters: earthquakes, fires, storms, famine and pestilence.

Shoku Nihongi doesn't however give clear relations between those disasters and onryō without minor exceptions like courtiers, it records several disasters in the late 8th centuries and rehabilitation of some then deceased royals in punishment and similar high ranked courtiers, as if the latter was response to the former. The form of rehabilitation by the imperial court sometimes culminated to their worship, their elevation to kami and thus dedication of shrines to those then deities, for example, as Prince Sawara and Sugawara no Michizane.

Though they do not always follow the ideal of justified revenge[citation needed], for example, several tales[citation needed] involve abusive husbands, but these husbands are rarely the target of the onryō's vengeance.[citation needed]

Examples of onryō vengeance[citation needed]

- How a Man's Wife Became a Vengeful Ghost and How Her Malignity Was Diverted by a Master of Divination - A neglected wife is abandoned and left to die. She is transformed into an onryō, and torments a local village until banished. Her husband remains unharmed.

- Of a Promise Broken - A samurai vows to his dying wife never to remarry. He soon breaks the promise, and his former wife's onryō beheads the new bride.

- Furisode - A heartbroken woman curses her famously beautiful kimono before dying. After, everyone who wears the garment soon dies.

Possibly the most famous onryō is Oiwa, from Yotsuya Kaidan. In this story the husband remains unharmed; however, he is the target of the onryō’s vengeance. Oiwa's vengeance on him isn't physical retribution, but rather psychological torment.

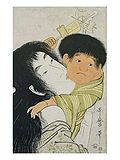

The appearance of an onryō

Traditionally[citation needed], onryō and other yūrei had no particular appearance. However, with the rising of popularity of Kabuki during the Edo period, a specific costume was developed.

Highly visual in nature, and with a single actor often assuming various roles within a play, Kabuki developed several visual shorthands that allowed the audience to instantly clue in as to which character is on stage, as well as emphasize the emotions and expressions of the actor.

A ghost costume consisted of three main elements:

- White burial kimono

- Wild, unkempt long black hair

- White and indigo face make-up called aiguma.

See also

- Japanese Urban Legends

- Kayako Saeki

- Sadako Yamamura

- S-Ko

- The Grudge

Notes

- ^ Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Annales des empereurs du japon, p. 72. at Google Books; Herman Ooms. (2009).Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan: the Tenmu Dynasty, 650-800, p. 219. at Google Books

References

- Iwasaka, Michiko and Toelken, Barre. Ghosts and the Japanese: Cultural Experiences in Japanese Death Legends, Utah State University Press, 1994. ISBN 0874211794

External links

- Ghoul Power - Onryou in the Movies Japanzine By Jon Wilks

- Yūrei-ga gallery at Zenshoan Temple

Japanese folklore

Folktales

Text collections Legendary creatures Mythology in popular culture · Legendary creatures Categories:- Japanese legendary creatures

- Ghosts

- Undead

- Japanese folklore

- Japanese horror fiction

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.