- Dolley Madison

-

This article is about a U.S. First Lady (the wife of James Madison). For the article on the baked goods brand, see Dolly Madison.

Dolley Madison

Dolley Madison, portrait by Gilbert Stuart, ca. 1804 First Lady of the United States In office

March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817Preceded by Martha Jefferson Randolph Succeeded by Elizabeth Monroe Personal details Born May 20, 1768

Guilford County, North CarolinaDied July 12, 1849 (aged 81)

Washington, D.C.Spouse(s) John Todd (1790-1793)

James Madison (1794-1836)Children John Payne Todd

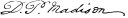

William Temple ToddOccupation First Lady of the United States of America Signature

Dolley Payne Todd Madison (May 20, 1768 – July 12, 1849) was the spouse of the fourth President of the United States, James Madison, and was First Lady of the United States from 1809 to 1817. She also occasionally acted as First Lady during the administration of Thomas Jefferson, fulfilling the ceremonial functions more usually associated with the President's wife, since Jefferson was a widower.[1]

Contents

Spelling of name

In the past, biographers and others stated that Madison's real name was Dorothea after her Aunt, or Dorothy and Dolley was a nickname. However, the registry of her birth with the New Garden Friends Meeting lists her name as Dolley and her will of 1841 states "I, Dolley P. Madison".[2] Based on manuscript evidence and the scholarship of her recent biographers, Dollie, spelled with an "i", appears to have been her given name at birth.[3]

Early life and first marriage

Miniature of Dolley, painted by James Peale, 1794

Miniature of Dolley, painted by James Peale, 1794

Dolley Payne was born on May 20, 1768, in the Quaker settlement of New Garden, North Carolina, in Guilford County.[4] Her parents, both Virginians, had moved there in 1765. Her mother, Mary Coles, a Quaker, married John Payne, a non-Quaker, in 1761. Three years later, he applied and was admitted to the Quaker Monthly Meeting in Hanover County, Virginia, and Dolley Payne was raised in the Quaker faith.

Dolley was one of 8 children, four boys (Walter, William Temple, Isaac, and John) and four girls (Dolley, Lucy, Anna, and Mary). In 1769, the family returned to Virginia.[4] As a young girl, she grew up in comfort in rural eastern Virginia, deeply attached to her mother's family.

In 1783, John Payne emancipated his slaves and moved his family to Philadelphia, where he went into business as a starch merchant. By 1789, however, his business hadDolley Payne was born on May 20, 1768, in the Quaker settlement of New Garden, North Carolina, in Guilford County sunk. He died in 1792. Dolley's mother initially made ends meet by opening a boarding house. A year later she moved to western Virginia to live with her daughter Lucy, who had married George Steptoe Washington, a nephew of George Washington. Mary Coles Payne took her two youngest children, Mary and John, with her. By then, Dolley Payne had married Quaker lawyer John Todd in January 1790. Their son, John Payne Todd, was born in 1792 and William Temple Todd in 1793. Her sister Anna lived with the Todds as well.

In the fall of 1793, yellow fever struck Philadelphia. Her husband and younger son, William Temple, both died in the epidemic, and Dolley Todd was left a widow at the age of twenty-five.

Second marriage

In May, 1794, James Madison asked his friend Aaron Burr to introduce him to Dolley Todd. Madison was seventeen years her senior and, at the age of forty-three, a long-standing bachelor.

The encounter apparently went smoothly, for a brisk courtship followed, and by August she had accepted his proposal of marriage. For marrying Madison, a non-Quaker, she was expelled from the Society of friends. They were married on September 15, 1794 and lived in Philadelphia for the next three years.

In 1797, after eight years in the House of Representatives, James Madison retired from politics. He took his family to Montpelier, the Madison family estate in Orange County, Virginia. There they expanded the house and settled in. They expected to remain as planters living quietly in the country, but when Thomas Jefferson became the third president of the United States, in 1801, he asked James Madison to serve as his Secretary of State. James Madison accepted, and the Madison family, consisting now of James, Dolley, her son John Payne, and her sister Anna, moved to Washington, D.C.. They moved to an extremely large house for the amount of their savings.

In Washington 1801-1817

Dolley Madison worked with the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe to furnish the White House.

In the approach to the 1808 presidential election, with Thomas Jefferson ready to retire, the Democratic-Republican caucus nominated James Madison to succeed him. James Madison was elected President, serving two terms from 1809 to 1817, with Dolley becoming official First Lady.

As the invading British army approached Washington during the War of 1812, Madison's slaves collected valuables like silver, Gilbert Stuart's famous Lansdowne portrait of George Washington, an original draft of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution during the year 1814.

However, in her own letter to her sister the day before Washington was burned (after hearing about the Battle of Bladensburg),[5] Dolley says she ordered that the painting be removed: "Our kind friend Mr. Carroll has come to hasten my departure, and in a very bad humor with me, because I insist on waiting until the large picture of General Washington is secured, and it requires to be unscrewed from the wall. The process was found too tedious for these perilous moments; I have ordered the frame to be broken and the canvas taken out"..... "It is done, and the precious portrait placed in the hands of two gentlemen from New York for safe keeping. On handing the canvas to the gentlemen in question, Messrs. Barker and Depeyster, Mr. Sioussat cautioned them against rolling it up, saying that it would destroy the portrait. He was moved to this because Mr. Barker started to roll it up for greater convenience for carrying." [6]

The White House historians JH McCormick (1904) and Gilson Willets (1908) identify the man in charge of removing the painting, as Jean Pierre Sioussat,[7] the first Master of Ceremonies of the White House,[8] quoted as follows: " a negro servant, named Paul Jennings, issued in 1865, A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison, in which he, as a White House employe, insists; 'She (Mrs. Madison) had no time for doing it It would have required a ladder to get it down. All she carried off was the silver in her reticule, as the British were thought to be but a few squares off, and were expected every moment. John Suse (meaning Jean Sioussat), a Frenchman, then doorkeeper, and still living, and McGraw, the President's gardener, took it down and sent it off on a wagon with some larger silver urns and other such valuables as could be hastily got together. When the British did arrive they ate up the very dinner that I had prepared for the President's party.'"

The White House historians give the accounts of further authorities regarding the First Lady's escape from fire of 1814:

"The friends with Mrs. Madison hurried her away (her carriage being previously ready), and she, with many other families, retreated with the fleeing army. In Georgetown they perceived some men before them carrying off the picture of General Washington (the large one by Stewart), which with the plate was all that was saved out of the President's house. Mrs. Madison lost all her own property. Mrs. Madison slept that night in the encampment, a guard being placed round her tent; the next day she crossed into Virginia, where she remained until Sunday, when she returned to meet her husband."

An eye-witness, writing for the Federal Republican, published at the time of the fire, says: "About ten o'clock on the night of the 24th ult., while the Capitol, the Navy Yard, the Magazine, and the buildings attached thereto, on Greenleaf's Point, were entirely in flames, I was sitting in the window of my lodging on the Pennsylvania Avenue, contemplating the solemn and awful scene, when about a hundred men passed the house, troops of the enemy, on their way toward the President's house. They walked two abreast preceded by an officer on foot, each armed with a hanger, and wearing a chapeau de bras. In the middle of the ranks were two men, each with a dark lanthorn. They marched quickly but silently. Some of them, however, were talking in the ranks, which being overheard by the officer, he called out to them 'Silence! If any man speaks in the ranks, I'll put him to death' 1 Shortly after they pushed on, I observed four officers on horseback, with chapeau de bras and side arms. They made up to the house, and pulling off their hats in a polite and social manner, wished us a good evening. The family and myself returned the salute, and I observed to them, 'Gentlemen! I presume you are officers of the British Army'. They replied they were. 'I hope, sir', said I, addressing one that rode up under the window, which I found to be Admiral Cockburn, 'that individuals and private property will be respected'. Admiral Cockburn and General Ross immediately replied: 'Yes, sir, we pledge our sacred honor that the citizens and private property shall be respected. Be under no apprehension. Our advice to you is to remain at home. Do not quit your houses'. Admiral Cockburn then inquired: 'Where is your President, Mr. Madison ?' I replied, "I could not tell, but supposed by this time at a considerable distance."

"They then observed that they were on their way to pay a visit to the President's house, which they were told was but a little distance ahead. They again requested that we would stay in our houses, where we would be perfectly safe, and bowing, politely, wished us good night, and proceeded on. I perceived the smoke coming from the windows of the President's house, and in a short time, that splendid and elegant edifice, reared at the expense of so much cost and labor, inferior to none that I have observed in the different parts of Europe, was wrapt in one entire flame. The large and elegant Capitol of the Nation on one side, and the splendid National Palace and Treasury Department on the other, all wrapt in flame, presented a grand and sublime, but, at the same time, an awful and sight."

In Montpelier 1817-1837

On April 6, 1817, Dolley and James Madison returned to their estate in Orange County, Virginia.

In 1830, Dolley Madison's son by her first marriage, Payne Todd, who had never found a career, went to debtors prison in Philadelphia. The Madisons sold land in Kentucky and mortgaged half of the Montpelier estate to pay Todd's debts.

James Madison died at Montpelier on June 28, 1836. Dolley remained at Montpelier for a year. One of her nieces, Anna Payne, came to live with her. Payne Todd also came for a stay, and Mrs. Madison organized and copied her husband's papers. In 1837, Congress authorized $30,000 as payment for the first installment of the Madison papers.

In the fall of 1837, Dolley Payne Madison decided to leave Montpelier for Washington, D.C., charging Payne Todd with the care of the plantation. She moved with Anna Payne into a house her sister Anna and her husband Richard Cutts had bought, located on Lafayette Square.

In Washington 1837-1849

A daguerreotype of Dolley in 1848, by Mathew B. Brady

A daguerreotype of Dolley in 1848, by Mathew B. Brady

While Madison was living in Washington, Payne Todd was unable to manage the plantation successfully due to alcoholism and resulting illness. Madison tried to raise money by selling the rest of James' papers. Unable to find a buyer for the papers, she sold the whole estate to pay off outstanding debts. Paul Jennings later recalled, "In the last days of her life, before Congress purchased her husband's papers, she was in a state of absolute poverty, and I think sometimes suffered for the necessaries of life. While I was a servant to Mr. Webster, he often sent me to her with a market-basket full of provisions, and told me whenever I saw anything in the house that I thought she was in need of, to take it to her. I often did this, and occasionally gave her small sums from my own pocket, though I had years before bought my freedom of her."[9] In 1848, Congress agreed to buy the rest of James Madison's papers for the sum of $22,000 or $25,000.

In 1842, she joined St. John's Episcopal Church, Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C. This church was also attended by members of the Madison and Payne families. Dolley Madison died at her home in Washington, DC at the age of 81. She was first interred in the Congressional Cemetery, Washington, DC., but later re-interred at Montpelier estate, Orange, Virginia.[10]

References

- ^ Catherine Allgor, A Perfect Union: Dolley Madison and the Creation of the American Nation (New York: Henry Holy & Co., 2006), 43

- ^ Will of Dolley Payne Todd Madison, February 1, 1841, Papers of Notable Virginia Families, MS 2988, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville Virginia, United States.

- ^ Allgor, 415-416; Richard N. Cote, Strength and Honor: the Life of Dolley Madison (Mount Pleasant, S.C.: Corinthian Books, 2005), 36-37

- ^ a b http://www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/madison/overview/chronology.html

- ^ Inside history of the White House, Gilson Willets, 1908

- ^ http://www.nationalcenter.org/WashingtonBurning1814.html

- ^ Inside history of the White House-the complete history of the domestic and official life in Washington of the nation's presidents and their families Gilson Willets - The Christian herald, 1908

- ^ The First Master of Ceremonies of the White House by JH McCormick,1904

- ^ http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/jennings/jennings.html

- ^ National First Ladies Library

Further reading

- Allgor, Catherine, Parlor Politics: In Which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000.

- Allgor, Catherine, A Perfect Union: Dolley Madison and the Creation of the American Nation. New York: Henry Holt, 2005.

- Arnett, Ethel Stephens, Mrs. James Madison: The Incomparable Dolley. Greensboro, N.C.: Piedmont Press, 1972.

- Brown, Rita Mae, Dolley: A Novel of Dolley Madison in Love and War. New York: Bantam Books, 1994.

- Cote', Richard N., Strength and Honor: The Life of Dolley Madison Mt. Pleasant, SC: Corinthian Books, 2004.

- Ketcham, Ralph. The Madisons at Montpelier: Reflections on the Founding Couple (University of Virginia Press, 2009). 200 pp. isbn 978-0-8139-2811-1

- Jennings, Paul. A Colored Man's Reminiscenes of James Madison, Brooklyn, George C. Beadle, 1865 pgs 12, 13, 15. http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/jennings/jennings.html

- Zall, Paul M, Dolley Madison (Presidential Wives Series). Huntington, NY: Nova History Publications, 2001.

External links

- http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/jennings/jennings.html - Paul Jennings book on James Madison

- The Dolley Madison Project - The life, legacy, and letters of Dolley Payne Madison

- The Dolley Madison Digital Edition - The online correspondence of Dolley Payne Madison

- Dolley Madison Letters - Digitized collection of letters from Dolley Madison - no login required

- Dolley Madison at Find a Grave

- Dolley Madison - PBS American Experience documentary

Honorary titles Preceded by

Martha Jefferson RandolphFirst Lady of the United States

1809–1817Succeeded by

Elizabeth Kortright MonroeCategories:- 1768 births

- 1849 deaths

- American Quakers

- First Ladies of the United States

- James Madison

- Madison family

- People from Greensboro, North Carolina

- People from Orange County, Virginia

- Spouses of members of the United States House of Representatives

- Spouses of United States Cabinet members

- Spouses of Virginia politicians

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.