- Mary Todd Lincoln

-

Mary Todd Lincoln

First Lady of the United States In office

March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865Preceded by Harriet Lane Succeeded by Eliza McCardle Johnson Personal details Born December 13, 1818

Lexington, Kentucky, U.S.Died July 16, 1882 (aged 63)

Springfield, Illinois, U.S.Spouse(s) Abraham Lincoln Children Robert Todd Lincoln

Edward Lincoln

Willie Lincoln

Tad LincolnMary Ann (née Todd) Lincoln (December 13, 1818 – July 16, 1882) was the wife of the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, and was First Lady of the United States from 1861 to 1865.

Contents

Life before the White House

Born in Lexington, Kentucky, the daughter of Robert Smith Todd, a banker, and Elizabeth Parker Todd, Mary was raised in comfort and refinement.[1] When Mary was six, her mother died; her father married Elizabeth "Betsy" Humphreys Todd in 1826.[2] Mary had a difficult relationship with her stepmother. From 1832, Mary lived in what is now known as the Mary Todd Lincoln House, an elegant 14-room residence in Lexington.[3] From her father's two marriages, Mary had a total of 14 siblings.

Mary Lincoln's paternal great-grandfather, David Levi Todd, was born in County Longford, Ireland, and emigrated through Pennsylvania to Kentucky. Her great-great maternal grandfather Samuel McDowell was born in Scotland then emigrated to and died in Pennsylvania. Other Todd ancestors came from England.[4]

Mary left home at an early age to attend a finishing school owned by a French woman, where the curriculum concentrated on French and dancing. She learned to speak French fluently, studied dance, drama, music and social graces. By the age of 20 she was regarded as witty and gregarious, with a grasp of politics. Mary began living with her sister Elizabeth Edwards in Springfield Illinois in October 1839. Elizabeth (wife of Ninian W. Edwards, son of a former governor) served as Mary's guardian while Mary lived in Springfield.[5] Mary was popular among the gentry of Springfield, and though she was courted by the rising young lawyer and politician Stephen A. Douglas and others, her courtship with Abraham Lincoln resulted in an engagement. Abraham Lincoln, then 33, married Mary Todd, age 23, on November 4, 1842, at the home of Mrs. Edwards in Springfield.

Lincoln and Douglas would eventually become political rivals in the great Lincoln-Douglas debates for a seat representing Illinois in the United States Senate in 1858. Although Douglas successfully secured the seat by election in the Illinois legislature, Lincoln became famous for his position on slavery which generated national support for him.

While Lincoln pursued his increasingly successful career as a Springfield lawyer, Mary supervised their growing household. Their home from 1844 until 1861 still stands in Springfield, and is now the Lincoln Home National Historic Site.

Their children, all born in Springfield, were:

- Robert Todd Lincoln (1843–1926) – lawyer, diplomat, businessman.

- Edward Baker Lincoln known as "Eddie" (1846–1850)

- William Wallace Lincoln known as "Willie" (1850–1862), died while Lincoln was President

- Thomas Lincoln known as "Tad" (1853–1871)

Of these four sons, only Robert and Tad survived to adulthood, and only Robert outlived his mother.

During Lincoln's years as an Illinois circuit lawyer, Mary Lincoln was often left alone to raise their children and run the household. Mary also supported her husband politically and socially, not least when Lincoln was elected president in 1860.

White House years

During her White House years, Mary Lincoln faced many personal difficulties generated by political divisions within the nation. Her family was from a border state where slavery was permitted.[6] In Kentucky, siblings not infrequently fought each other in the Civil War[7] and Mary's family was no exception. Several of her half-brothers served in the Confederate Army and were killed in action, and one full brother served the Confederacy as a surgeon.[8] Mary, however, staunchly supported her husband in his quest to save the Union and maintained a strict loyalty to his policies. Nevertheless it was a challenge for Mary, a Westerner, to serve as her husband's First Lady in Washington, D.C., a political center dominated by eastern and southern culture. Lincoln was regarded as the first "western" president, and Mary's manners were often criticized as coarse and pretentious.[9][10] It was difficult for her to negotiate White House social responsibilities and rivalries,[11] spoils-seeking solicitors,[12] and baiting newspapers[10] in a climate of high national intrigue in Civil War Washington.

Mary suffered from severe headaches throughout her adult life [13] as well as protracted depression.[14] During her White House years, she also suffered a severe head injury in a carriage accident.[15] A history of public outbursts throughout Lincoln's presidency, as well as excessive spending, has led some historians and psychologists to speculate that Mary in fact suffered from bipolar disorder.[16][17]

During her tenure at the White House, she often visited hospitals around Washington where she gave flowers and fruit to wounded soldiers, and transcribed letters for them to send their loved ones.[18][19] From time to time, she accompanied Lincoln on military visits to the field. She also hosted many social functions, and has often been blamed for spending too much on the White House, but she reportedly felt that it was important to the maintenance of prestige of the Presidency and the Union.[19]

Assassination survivor and later life

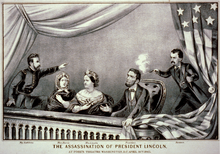

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln. From left to right: Henry Rathbone, Clara Harris, Mary Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln. From left to right: Henry Rathbone, Clara Harris, Mary Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth

In April 1865, as the Civil War came to an end, Mrs. Lincoln expected to continue as the First Lady of a nation at peace. However, on April 14, 1865, as Mary Lincoln sat with her husband to watch the comic play Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre, President Lincoln was shot in the back of the head by an assassin. Mrs. Lincoln accompanied her husband across the street to the Petersen House, where Lincoln's Cabinet was summoned. Mary and her son Robert sat with Lincoln throughout the night, until he died the following day, April 15, at 7:22 am.[20]

Mary received messages of condolence from all over the world, many of which she attempted to answer personally. To Queen Victoria she wrote: "I have received the letter which Your Majesty has had the kindness to write. I am deeply grateful for this expression of tender sympathy, coming as they do, from a heart which from its own sorrow, can appreciate the intense grief I now endure." Victoria herself had suffered the loss of Prince Albert four years earlier.[21]

As a widow, Mrs. Lincoln returned to Illinois. In 1868, Mrs. Lincoln's former confidante, Elizabeth Keckly, published Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty years a slave, and four years in the White House. Although this book provides valuable insight into the character and life of Mary Todd Lincoln, at the time the former First Lady regarded it as a breach of friendship.

In an act approved July 14 1870, the United States Congress granted Mrs. Lincoln a life pension in the amount of $3,000 a year, by an insultingly low margin.[22] Mary had lobbied hard for such a pension, writing numerous letters to Congress and urging patrons such as Simon Cameron to petition on her behalf, insisting that she deserved a pension just as much as the widows of soldiers.[23]

For Mary Lincoln, the death of her son Thomas (Tad), in July 1871, following the death of two of her other sons and her husband, led to an overpowering sense of grief.[24] Mrs. Lincoln's sole surviving son, Robert Lincoln, a rising young Chicago lawyer, was alarmed at his mother's increasingly erratic behavior. In March 1875, during a visit to Jacksonville, Florida, Mary became unshakably convinced that Robert was deathly ill. She traveled to Chicago to see him, but found he wasn't sick. In Chicago she told her son that someone had tried to poison her on the train and that a "wandering Jew" had taken her pocketbook but would return it later.[25] During her stay in Chicago with her son, Mary spent large amounts of money on items she never used, such as draperies which she never hung and elaborate dresses which she never wore, as she wore only black after her husband's assassination. She would also walk around the city with $56,000 in government bonds sewn into her petticoats. Despite this large amount of money and the $3,000 a year stipend from Congress, Mrs. Lincoln had an irrational fear of poverty. After Mrs. Lincoln nearly jumped out of a window to escape a non-existent fire, her son determined that she should be institutionalized.[26]

Mrs. Lincoln was committed to a psychiatric hospital in Batavia, Illinois, in 1875. After the court proceedings, Mary was so enraged that she attempted suicide. She went to the hotel pharmacist and ordered enough laudanum to kill herself. However, the pharmacist realized what she was planning to do and gave her a placebo.[26]

On May 20, 1875, she arrived at Bellevue Place, a private sanitarium in the Fox River Valley.[27] Three months after being committed to Bellevue Place, Mary Lincoln engineered her escape. She smuggled letters to her lawyer, James B. Bradwell, and his wife, Myra Bradwell, who was not only her friend but also a feminist lawyer and fellow spiritualist. She also wrote to the editor of the Chicago Times. Soon, the public embarrassments Robert (who now controlled his mother's finances) had hoped to avoid were looming, and his character and motives were in question. The director of Bellevue, who at Mary's trial had assured the jury she would benefit from treatment at his facility, now in the face of potentially damaging publicity declared her well enough to go to Springfield to live with her sister as she desired.[28] She was released into the custody of her sister, Mrs. Elizabeth Edwards, in Springfield and in 1876 was once again declared competent to manage her own affairs. The committal proceedings led to a profound estrangement between Robert and his mother, and they never fully reconciled.

Mrs. Lincoln spent the next four years traveling throughout Europe and taking up residence in Pau, France. However, the former First Lady's final years were marked by declining health. She suffered from severe cataracts that affected her eyesight. This condition may have contributed to her increasing susceptibility to falls. In 1879, she suffered spinal-cord injuries in a fall from a step ladder.

Death

Mary Todd Lincoln's crypt

During the early 1880s, Mary Lincoln was confined to the Springfield, Illinois residence of her sister Elizabeth Edwards. She died there on July 16, 1882, age 63, and was interred within the Lincoln Tomb in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield alongside her husband.[29]

Family

Her sister Elizabeth Todd was the daughter-in-law of Illinois Governor Ninian Edwards. Elizabeth's daughter Julia Edwards married Edward L. Baker, editor of the "Illinois State Journal" and son of Congressman David Jewett Baker. Her half-sister Emilie Todd married CS General Benjamin Hardin Helm, son of Kentucky Governor John L. Helm. Governor Helm's wife was a 1st cousin 3 times removed of Colonel John Hardin who was related to three Kentucky congressmen.

One of Mary Todd's cousins was Kentucky Congressman/US General John Blair Smith Todd. Another cousin, William L. Todd,[30] created the original Bear Flag for the California Republic in 1846.

References

- ^ Catherine Clinton, Mrs. Lincoln: A Life (New York: HarperCollins, 2010) ISBN 0060760419

- ^ It has been suggested that Robert Smith Todd and Elizabeth Parker were double first cousins, his paternal aunt married to her father, and her paternal aunt married to his father.Mary Todd Biography

- ^ Mary Todd Lincoln House. Nps.gov (1977-06-09). Retrieved on 2011-09-14.

- ^ Mary Lincoln. Firstladies.org. Retrieved on 2011-09-14.

- ^ "Springfield". Lincoln's Life. Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission. http://www.abrahamlincoln200.org/lincolns-life/bio/lincoln-in-illinois/springfield.aspx. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ MacLean, Maggie. "Abolishing slavery in America." Accessed Dec. 13, 2010

- ^ Kentucky Historical Society, moments 14.pdf "Kentucky's Abraham Lincoln: Divided Kentucky families during the Civil War." Feb. 2008-Feb. 2010. Accessed Dec. 13, 2010

- ^ Neely, Mark E., Jr. (1996). "The secret treason of Abraham Lincoln's brother-in-law". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 17 (1): 39–43. JSTOR 20148933. http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jala/17.1/neely.html.

- ^ Phillips, Ellen Blue. Sterling Biographies: Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to President. New York: Sterling, 2007

- ^ a b The Lincoln Institute, The Lehrman Institute, and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. "Mr. Lincoln's White House: Mary Todd Lincoln (1818–1882)." No date. Accessed Dec. 13, 2010

- ^ Flood, Charles Bracelen. 1864: Lincoln at the Gates of History New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

- ^ Norton, Mary Beth, et al. A People and a Nation: a History of the United States. Since 1865, Volume 2. Florence, KY: Wadsworth Publishing, 2011.

- ^ NNDB/Soylent Communications, "Mary Todd Lincoln." 2010. Accessed Dec. 13, 2010

- ^ Holden, Charles J. (2004). "Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A house divided". Film & History: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 34 (1): 76–77. doi:10.1353/flm.2004.0019. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/film_and_history/v034/34.1holden.html.

- ^ Emerson, Jason (2006). "The madness of Mary Lincoln". American Heritage Magazine 57 (3). http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/2006/3/2006_3_56.shtml.

- ^ Graham, Ruth (2010-02-14). "Was Mary Todd Lincoln bipolar?". Slate. http://www.slate.com/id/2244675/. Retrieved 2010-10-26.

- ^ Bach, Jennifer (2005). "Was Mary Lincoln bipolar?". Journal of Illinois History.

- ^ The Lincoln Institute, The Lehrman Institute, and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. "Mr. Lincoln's White House: Campbells General Hospital." Accessed Dec. 13, 2010

- ^ a b Emerson, Jason. "Mary Todd Lincoln." The New York Times, Dec. 13, 2010. Accessed Dec. 13, 2010

- ^ Emerson, Jason (2008) The Madness of Mary Lincoln

- ^ Turner, Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters, Fromm International Pub. Corp., 1987 ISBN 0880640731 p. 230

- ^ Acts of 1870, Chapter 277. Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved on 2011-09-14.

- ^ Jennifer Bach, "Acts of Remembrance: Mary Todd Lincoln and Her Husband's Legacy"

- ^ Jason Emerson "The Madness of Mary Lincoln," American Heritage, June/July 2006.

- ^ / The Madness of Mary Lincoln. Americanheritage.com. Retrieved on 2010-11-13.

- ^ a b Emerson, Jason (June/July 2006). "The Madness of Mary Lincoln". American Heritage. http://www.americanheritage.com/people/articles/web/20060601-mary-todd-lincoln-abraham-lincoln-robert-todd-lincoln-batavia-illinois-sanitarium-james-bradwell-marriage.shtml. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ^ Mary Todd Lincoln's Stay at Bellevue Place. Showcase.netins.net. Retrieved on 2010-11-13.

- ^ Wellesley Centers for Women – The Madness of Mary Todd Lincoln | Women's Review of Books-May/June 2008. Wcwonline.org (2010-06-24). Retrieved on 2010-11-13.

- ^ "Mary Todd Lincoln". Presidential First Lady. Find a Grave. Jan 01, 2001. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=1341. Retrieved Aug 18, 2001.

- ^ Mary Todd Genealogy See Generation 5, Child "C" Grandchild 3 for William L (WLT), Generation 5 Child "G" = Generation 6 (grand) Child D for Mary (MATL) Shorthand Common Ancestor 5 WLT = 5C3, MATL= 5G4 = 6D = 7. 5C & 5G are brothers, which makes their children first cousins. The Revolutionary William is generation 3 child "I" The MATL/WLT line follows 3B to 4D to 5'

Honorary titles Preceded by

Harriet LaneFirst Lady of the United States

1861–1865Succeeded by

Eliza McCardle JohnsonExternal links

- White House profile

- Works by or about Mary Todd Lincoln in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Mary Todd Lincoln Quotes

Categories:- 1818 births

- 1882 deaths

- Abraham Lincoln

- Lincoln family

- First Ladies of the United States

- Spouses of Illinois politicians

- Spouses of members of the United States House of Representatives

- People with bipolar disorder

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.