- Pyramid of Cestius

-

Pyramid of Cestius

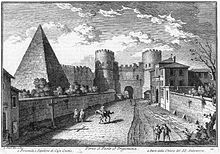

The Pyramid of CestiusLocation Regione XIII Aventinus Built in circa 12 BC Built by/for Gaius Cestius Type of structure Pyramid Related articles None. The Pyramid of Cestius (in Italian, Piramide di Caio Cestio or Piramide Cestia) is an ancient pyramid in Rome, Italy, near the Porta San Paolo and the Protestant Cemetery. It stands at a fork between two ancient roads, the Via Ostiensis and another road that ran west to the Tiber along the approximate line of the modern Via della Marmorata. Due to its incorporation into the city's fortifications, it is today one of the best-preserved ancient buildings in Rome.

Contents

Physical attributes

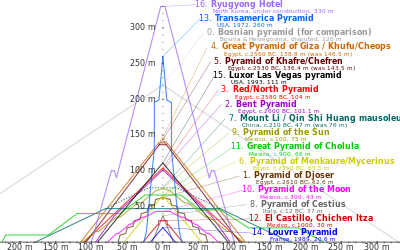

The pyramid was built about 18 BC–12 BC as a tomb for Gaius Cestius, a magistrate and member of one of the four great religious corporations in Rome, the Septemviri Epulonum. It is of brick-faced concrete covered with slabs of white marble standing on a travertine foundation, measuring 100 Roman feet (29.6 m) square at the base and standing 125 Roman feet (37 m) high.[1]

In the interior is the burial chamber, a simple barrel-vaulted rectangular cavity measuring 5.95 metres long, 4.10 m wide and 4.80 m high. When it was (re)discovered in 1660, the chamber was found to be decorated with frescoes, which were recorded by Pietro Santi Bartoli, but only the scantest traces of these now remain. There was no trace left of any other contents in the tomb, which had been plundered in antiquity. The tomb had been sealed when it was built, with no exterior entrance; it is not possible for visitors to access the interior,[1] except by special permission typically only granted to scholars.

Inscriptions

A dedicatory inscription is carved into the east and west flanks of the pyramid, so as to be visible from both sides. It reads:

- C · CESTIVS · L · F · POB · EPULO · PR · TR · PL

- VII · VIR · EPOLONVM

- Caius Cestius, son of Lucius, of the gens Pobilia, member of the College of Epulones, praetor, tribune of the plebs, septemvir of the Epulones [1] [2]

Below the inscription on the east-facing side is a second inscription recording the circumstances of the tomb's construction. This reads:

- OPVS · APSOLVTVM · EX · TESTAMENTO · DIEBVS · CCCXXX

- ARBITRATV

- PONTI · P · F · CLA · MELAE · HEREDIS · ET · POTHI · L

- The work was completed, in accordance with the will, in 330 days, by the decision of the heir [Lucius] Pontus Mela, son of Publius of the Claudia, and Pothus, freedman [1]

Another inscription on the east face is of modern origins, having been carved on the orders of Pope Alexander VII in 1663. Reading INSTAVRATVM · AN · DOMINI · MDCLXIII, it commemorates excavation and restoration work carried out in and around the tomb between 1660–62.[1]

At the time of its construction, the Pyramid of Cestius would have stood in open countryside (tombs being forbidden within the city walls). Rome grew enormously during the imperial period, and, by the third century AD, the pyramid would have been surrounded by buildings. It originally stood in a low-walled enclosure, flanked by statues, columns and other tombs.[3] Two marble bases were found next to the pyramid during excavations in the 1660s, complete with fragments of the bronze statues that originally had stood on their tops. The bases carried an inscription recorded by Bartoli in an engraving of 1697:

- M · VALERIVS · MESSALLA · CORVINVS ·

- P · RVTILIVS · LVPVS · L · IVNIVS · SILANVS ·

- L · PONTIVS · MELA · D · MARIVS ·

- NIGER · HEREDES · C · CESTI · ET ·

- L · CESTIVS · QVAE · EX · PARTE · AD ·

- EVM · FRATRIS · HEREDITAS ·

- M · AGRIPPAE · MVNERE · PER ·

- VENIT · EX · EA · PECVNIA · QVAM ·

- PRO · SVIS · PARTIEVS · RECEPER ·

- EX · VENDITIONE · ATTALICOR ·

- QVAE · EIS · PER · EDICTVM ·

- AEDILIS · IN · SEPVLCRVM ·

- C · CESTI · EX · TESTAMENTO ·

- EIVS · INFERRE · NON · LICVIT ·

This identifies Cestius' heirs as Marcus Valerius Messala Corvinus, a famous general; Publius Rutilius Lupus, an orator whose father of the same name had been consul in 90 BC; and Lucius Junius Silanus, a member of the distinguished gens Junia. The heirs had set up the statues and bases using money raised from the sale of valuable cloths (attalici). Cestius had stated in his will that the cloths were to be deposited in the tomb, but this practice had been forbidden by a recent edict passed by the aediles.[1]

History

The sharply pointed shape of the pyramid is strongly reminiscent of the pyramids of Nubia, in particular of the kingdom of Meroë, which had been attacked by Rome in 23 BC. The similarity suggests that Cestius had possibly served in that campaign and perhaps intended the pyramid to serve as a commemoration. His pyramid was not the only one in Rome; a larger one—the so-called "pyramid of Romulus"—of similar form but unknown origins stood between the Vatican and the Mausoleum of Hadrian but was demolished in the 16th century.[1]

Some writers have questioned whether the Roman pyramids were modelled on the much less steeply pointed Egyptian pyramids exemplified by the famous pyramids of Giza. However, the relatively shallow Giza-type pyramids were not exclusively used by the Egyptians; steeper pyramids of the Nubian type were favoured by the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt that had been brought to an end in the Roman conquest of 30 BC. The pyramid was, in any case, built during a period when Rome was going through a fad for all things Egyptian. The Circus Maximus was adorned by Augustus with an Egyptian obelisk, and pyramids were built elsewhere in the Roman Empire around this time; the Falicon pyramid near Nice in France was suspected by some to have been constructed by Roman legionaries who followed an Egyptian cult,[4] but more recent research has indicated that it was actually built between 1803 and 1812.[5]

During the construction of the Aurelian Walls between 271 and 275, the pyramid was incorporated into the walls to form a triangular bastion. It was one of many structures in the city to be reused to form part of the new walls, probably to reduce the cost and enable the structure to be built more quickly. It still forms part of a well-preserved stretch of the walls, a short distance from the Porta San Paolo.[6]

The origins of the pyramid were forgotten during the Middle Ages. The inhabitants of Rome came to believe that it was the tomb of Remus (Meta Remi) and that its counterpart near the Vatican was the tomb of Romulus, a belief recorded by Petrarch.[7][8] Its true provenance was clarified by Pope Alexander VII's excavations in the 1660s, which cleared the vegetation that had overgrown the pyramid, uncovered the inscriptions on its faces, tunnelled into the tomb's burial chamber and found the bases of two bronze statues that had stood alongside the pyramid.[1]

The pyramid was an essential sight for many who undertook the Grand Tour in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was much admired by architects, becoming the primary model for pyramids built in the West during this period.[9] Percy Bysshe Shelley described it as "one keen pyramid with wedge sublime" in Adonaïs, his 1821 elegy for John Keats. In turn the English novelist and poet Thomas Hardy saw the pyramid during a visit to the nearby Protestant Cemetery in 1887 and was inspired to write a poem, Rome: At the Pyramid of Cestius near the Graves of Shelley and Keats, in which he wondered: "Who, then was Cestius, / and what is he to me?"[10]

In 2001, the pyramid's entrance and interior underwent restoration. In 2011, further work was announced to clean and restore the pyramid's badly-damaged external walls, through which water seepage has endangered the frescoes within. The €1-million project will be sponsored by Japanese businessman Yuzu Yakhi and supervised by Italy's Ministry of Cultural Heritage.[11]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide, First, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 59, 364–366. ISBN 0-19-288003-9

- ^ Di Meo, Chiara: La piramide di Caio Cestio e il cimitero acattolico del Testaccio: trasformazione di un'immagine tra vedutismo e genius loci. Rome: Palombi Fratelli, 2008

- ^ Lawrence J. F Keppie, Understanding Roman Inscriptions, pp. 104–105. Routledge, 1991. ISBN 0-415-15143-0

- ^ James Stevens Curl, The Egyptian Revival: Ancient Egypt as the Inspiration for Design Motifs in the West, pp. 39–40. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-36118-4

- ^ "La pyramide de Falicon et la grotte des Ratapignata". 2007. http://www.ipaam.fr/. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ Aldrete, Gregory S (2004). Daily Life In The Roman City: Rome, Pompeii, And Ostia, Greenwood Press, 2004, pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-313-33174-X

- ^ Eileen Gardiner, Francis Morgan Nichols, The Marvels of Rome, p. 86. Italica Press, Incorporated, 1986. ISBN 0-934977-02-X

- ^ Augustus J.C. Hare, Walks in Rome, p. 268. Adamant Media Corporation, 2001. ISBN 1-4021-7139-0

- ^ Jean-Marcel Humbert, Clifford A. Price, Imhotep Today: Egyptianizing Architecture, p. 27. Routledge Cavendish, 2003. ISBN 1-84472-006-3

- ^ Radford, Andrew (2008). "'Fallen Angels': Hardy's Shelleyan Critique in the Final Wessex Novels". Romantic echoes in the Victorian era. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. p. 107. ISBN 9780754657880.

- ^ "Restoration of Rome's Pyramid". Wanted in Rome. 26 January 2011. http://www.wantedinrome.com/news/news.php?id_n=7819. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

External links

- Sepulchrum Caii Cestii in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

Coordinates: 41°52′35″N 12°28′51″E / 41.87639°N 12.48083°E

Categories:- 1st-century BC architecture

- Ancient Roman tombs and cemeteries in Rome

- European pyramids

- Latin inscriptions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.