- Colfax massacre

-

Further information: Ulysses S. Grant presidential administration

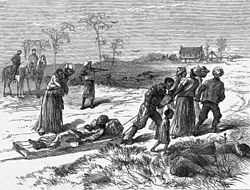

Gathering the dead after the Colfax massacre in Harper's Weekly, May 10, 1873

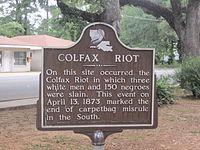

Gathering the dead after the Colfax massacre in Harper's Weekly, May 10, 1873 Colfax Riot historical marker in Colfax refers to "carpetbag misrule in the South."

Colfax Riot historical marker in Colfax refers to "carpetbag misrule in the South."

The Colfax massacre or Colfax Riot (as the events are termed on the official state historic marker) occurred on Easter Sunday, April 13, 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana, the seat of Grant Parish, during Reconstruction, when white militia attacked freedmen at the Colfax courthouse. Three whites and 80-150 freedmen died in the confrontation.

Contents

Summary

In the wake of a contested election for governor of Louisiana and local offices, a white militia, armed with rifles and a small cannon, overpowered freedmen and state militia (also black) trying to control the Grant Parish courthouse in Colfax.[1][2] White Republican officeholders were not attacked. Most of the freedmen were killed after they surrendered, and nearly 50 were killed later that night after being held as prisoners for several hours. Estimates of the number of dead varied. Two U.S. Marshals who visited the site on April 15, 1873, and buried dead reported 62 fatalities.[3] A military report to Congress in 1875 identified 81 black men who had been killed by name, and also estimated that 15-20 bodies were thrown into the Red River and another 18 secretly buried — for a grand total of "at least 105."[3] A state historical marker from 1950 noted fatalities as three whites and 150 blacks.[4] Taking into account all available estimates, author Charles Lane has estimated a minimum death toll of 62 and maximum death toll of 81.[3]

The attack had the most fatalities of violent events following the disputed contest in 1872 between Republicans and Democrats for the Louisiana governor's office, in which both candidates claimed victory. Although the Fusionist-dominated state "returning board", which ruled on validity of votes, at first declared John McEnery and his Democratic slate the winners, the board split. A pro-Kellogg faction declared Republican William P. Kellogg the victor. Both men held inauguration parties. A Republican federal judge in New Orleans finally ruled that the Republican-majority legislature be seated.[5]

The background of the situation was the struggle for power in the postwar environment, with a growing insurgency among former Confederates in the state. In Louisiana "every election between 1868 and 1876 was marked by rampant violence and pervasive fraud."[6] White Democrats worked to regain power, officially or unofficially.

Federal prosecution and conviction of a few perpetrators at Colfax under the Enforcement Act led to a key Supreme Court case, United States v. Cruikshank. In this 1876 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that protections of the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to the actions of individuals, but only to the actions of state governments. Thus, the federal government could no longer use the Enforcement Act of 1870 to prosecute actions by paramilitary groups, private militias such as the White League, which had chapters forming across Louisiana beginning in 1874.

In the late 20th and early 21st century, there has been increasing attention given to the events at Colfax and the Supreme Court case, and their meaning in U.S. history.

Background

In 1864 federals in Louisiana gave the vote to only a few blacks based on Union military service, payment of taxes and "intellectual fitness," which was in line with Lincoln's ten-percent plan for reconstructing Louisiana. In March 1865 Unionist planter James Madison Wells became governor and at first opposed Negro suffrage. However, attempts by ex-Confederate legislatures to make blacks work under a system of contracts that closely resembled slavery caused Wells to support allowing blacks to vote and disfranchising ex-Confederates (whites) instead. To accomplish this, he scheduled a convention for July 30, 1866. It was postponed because of the New Orleans Massacre, which left thirty-eight dead, all but four of them black. When President Andrew Johnson blamed the massacre on Republican agitation, a popular national backlash against Johnson's policies caused voters to elect a majority Republican Congress in 1866. The Civil Rights Act, passed on April 9, 1866 over Andrew Johnson's veto, ended the Black Codes. On July 16, 1866, Congress extended the life of the Freedman's Bureau over Johnson's veto. Beginning on March 2, 1867 the Reconstruction Act, passed over Johnson's veto, required that blacks be allowed to vote and that reconstructed Southern states ratify the Fourteenth Amendment.

By April 1868, Congressional legislation resulted in a Republican state government for Louisiana. However, opposition in Louisiana to suffrage for blacks resulted in 1,081 political murders from April to November 1868. Almost all of the victims were black, and some of the whites who were killed were Republicans. In addition to the dead, other men were flogged or had their homes burned to discourage them from voting. President Johnson prevented the Republican governor of Louisiana from using either the state militia or U.S. forces to stop terrorist groups such as the Knights of the White Camellia from threatening blacks who tried to vote.[3]

William Smith Calhoun owned a 14,000-acre (57 km2) plantation in the area that later became Grant Parish. Although Calhoun was a former slaveowner, he lived with a mixed-race woman as his common-law wife and supported black equality. On election day of November 1868, he led a group of freedmen to vote. The ballot box was originally to be at a store owned by John Hooe, who threatened to whip blacks who tried to vote. Calhoun arranged for the ballot box to be switched to a plantation store owned by a Republican instead. Republicans got 318 votes, with only 49 for the Democrats. A group of whites threw the ballot box into the Red River, and Democrats arrested Calhoun for alleged election fraud. With the ballot box thrown out, Democrat Michael Ryan claimed a landslide victory. After black Republican election commissioner Hal Frazier was shot by whites, Calhoun drafted a bill which created a new parish out of part of Winn Parish and part of Rapides Parish. Calhoun hoped that he would have more political control over things that happened in the new parish, named after Grant.[3]

After Ulysses S. Grant became President in 1868, he lobbied hard for the Fifteenth Amendment (ratified February 3, 1870), which guaranteed that blacks, most of whom were newly freed slaves, would have an equal right to vote. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and other supremacist groups continued violent attacks and killed scores of blacks in South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi and elsewhere to discourage their voting in the 1870 elections. On May 31, 1870 Congress passed an Enforcement Act based on the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. They followed this with the Ku Klux Klan Act, enacted April 20, 1871. Grant used this authority to suspend writ of habeas corpus and use the army to stop Klan violence.[3]

Governor Henry Clay Warmoth struggled to maintain political balance in Louisiana. Among his appointments, he installed William Ward, a black Union veteran, as commanding officer of Co.A, 6th Infantry Regiment, Louisiana State Militia, a new unit to be based in Grant Parish to help control the violence there and in other Red River parishes. Ward, born a slave in 1840 in Charleston, South Carolina, had learned to read and write as a valet to a master in Richmond, Virginia. In 1864 he escaped and went to Fortress Monroe, where he joined the Union Army and served until after General Robert E. Lee's surrender. About 1870 he came to Grant Parish, where he had a friend, and quickly became active among local blacks in the Republican Party. After his appointment to the militia, Ward recruited other freedmen for his forces, several of whom had been veterans.[7]

The Louisiana election of 1872

In Louisiana, Republican governor Henry Clay Warmoth defected to the Liberal Republicans (a group that opposed Reconstruction) in 1872. Warmoth previously supported a constitutional amendment that allowed former Confederates to vote again. A "Fusionist" coalition of Liberal Republicans and Democrats nominated ex-Confederate battalion commander John McEnery to succeed him as governor. In return, Democrats were to send Warmoth to Washington as a U.S. Senator. Opposing McEnery was Republican William Pitt Kellogg, one of Louisiana's U.S. Senators. Voting on November 4, 1872 resulted in dual governments, as a Fusionist-dominated returning board declared McEnery the winner while a faction of the board proclaimed Kellogg the winner. Both administrations held inaugural ceremonies and certified their lists of local candidates.

It took some time for a Republican federal judge in New Orleans to order that Kellogg and the Republican-majority legislature were to be seated, and for Grant to authorize U.S. army troops to protect Kellogg's government. McEnery's faction tried to seize the state arsenal at Jackson Square, but Kellogg's militia seized dozens of leaders of McEnery's faction and controlled New Orleans.[3] Unrest was so marked that McEnery organized his own militia. In March he took control of the state house and police stations in New Orleans, where the state government was then located, in what was known as the Battle of Jackson Square. His forces retreated before the arrival of Federal troops.[6] Warmoth was subsequently impeached by the state legislature in a bribery scandal stemming from his actions in the 1872 election.

Warmoth appointed Democrats as parish registrars who ensured the voter rolls included as many whites and as few freedmen as possible. A number of registrars changed the registration site without notifying blacks. They also required blacks to prove they were over 21, while knowing that former slaves did not have birth certificates. In Grant Parish one plantation owner threatened to expel black Republican voters from homes they rented on his land. Fusionists also tampered with ballot boxes on election day. One was found with a hole in it, apparently used for stuffing the ballot box. As a result, Grant Parish Fusionists claimed a landslide victory, even though blacks outnumbered whites by 776 to 630.

Warmoth issued commissions to Fusionist Alphonse Cazabat and Christopher Columbus Nash, elected parish judge and sheriff, respectively. Like many white men in the South, Nash was a Confederate veteran (as an officer, he had been held for a year and a half as a prisoner of war at Johnson's Island in Ohio). Cazabat and Nash took their oaths of office in the Colfax courthouse on January 2, 1873. They then dispatched the documents to Governor McEnery in New Orleans.

William Pitt Kellogg countered by issuing commissions to the Republican slate for Grant Parish on January 17 and 18. By then Nash and Cazabat controlled the courthouse. Republican Robert C. Register insisted that he, not Alphonse Cazabat, was the parish judge, and that Republican Daniel Wesley Shaw, not Nash, was to be the sheriff. On the night of March 25, the Republicans seized the courthouse and took their oaths of office. They sent their oaths to the Kellogg administration in New Orleans.[3]

Grant Parish was one of a number of new parishes created by the Republican government in an effort to build local support in the state. Both the land and its people were originally tied to the Calhoun family, whose plantation had covered more than the borders of the new parish. The freedmen had been slaves on the plantation. The parish also took in less-developed hill country. The total population had a narrow majority of 2400 freedmen, who mostly voted Republican, and 2200 whites, mostly Democrats. Statewide political tensions were reflected in the rumors going around each community, often about fears of attacks or outrages, which added to local tensions.[8]

Colfax courthouse conflict

With support from the Federal government, Republican William Kellogg was certified and assumed control as Louisiana governor. In late March, Republicans Register and Shaw occupied their offices in the Colfax courthouse. Fearful that the Democrats might try to take over the local parish government, freedmen in Colfax started to create trenches around the courthouse and drilled to keep alert. They held the town for three weeks.[9]

On March 28, Nash, Cazabat, Hadnot and other white Fusionists called for armed whites to retake the courthouse on April 1. Republicans Register, Shaw, Flowers and others countered by calling for their own posse of armed blacks to defend the courthouse. Black Republicans Lewis Meekins and state militia captain William Ward, a black Union veteran, raided the homes of leaders Judge William R. Rutland, Bill Cruikshank and Jim Hadnot. Gunfire erupted between whites and blacks on April 2 and again on April 5, but the shotguns were too inaccurate to do any harm. The two sides arranged for peace negotiations. Peace ended when a white supremacist shot and killed a black man named Jesse McKinney. Another armed conflict on April 6 ended with whites' fleeing from armed blacks.[3] With all the unrest, black women and children joined the men at the courthouse for protection.

William Ward, the commanding officer of Company A, 6th Infantry Regiment, Louisiana State Militia, headquartered in Grant Parish, had also been elected state representative from the parish on the Republican ticket.[10] He wrote to Governor Kellogg seeking U.S. troops for reinforcement and gave the letter to Calhoun for delivery. The latter took the steamboat LaBelle down the Red River but was captured by Paul Hooe, Hadnot and Cruikshank. They ordered Calhoun to tell blacks to leave the courthouse. The black defenders refused but were threatened by armed whites commanded by Nash. To recruit armed whites for his militia, Nash had contributed to lurid rumors that blacks were preparing to kill all the white men and take the white women as their own.[3][11] On April 8 the anti-Republican Daily Picayune reported the following:

“ THE RIOT IN GRANT PARISH. FEARFUL ATROCITIES BY THE NEGROES. NO RESPECT SHOWN TO THE DEAD.[3] ” Nash got reinforcements from groups such as the KKK. His group got a four-pound cannon that could fire iron slugs. As the Klansman Dave Paul said, "Boys, this is a struggle for white supremacy."[3]

Suffering from tuberculosis and rheumatism, militia captain Ward took a steamboat downriver to New Orleans on April 11. He planned to seek armed help for Colfax directly from Kellogg. He was not there for the following events.[12]

Riot and massacre

Cazabat had directed Nash as sheriff to put down what he called a riot. Nash gathered an armed white militia and veteran officers from Rapides, Winn and Catahoula parishes. He did not move his forces toward the courthouse until noon on Easter Sunday, April 13. Nash led more than 300 armed white men, most on horseback and armed with rifles. Nash reportedly ordered the defenders of the courthouse to leave. When that failed, Nash gave women and children camped outside the courthouse thirty minutes to clear out. After they left, the shooting began. The fighting continued for several hours with few casualties. When Nash's militia maneuvered the cannon behind the building, some of the defenders panicked and left the courthouse.

About 60 defenders ran into nearby woods and jumped into the river. Nash sent men on horseback after the fleeing black Republicans, and his militia killed most of them on the spot. Later, Nash's besiegers directed a black captive to set the courthouse roof on fire. The defenders then displayed white flags for surrender: one made from a shirt, the other from a page of a book. The shooting stopped.

Nash's group approached and called for those surrendering to throw down their weapons and come outside. What happened next is in dispute. According to the reports of some whites, James Hadnot was shot and wounded by someone from the courthouse. "In the Negro version, the men in the courthouse were stacking their guns when the white men approached, and Hadnot was shot from behind by an overexcited member of his own force." Hadnot died later, after being taken downstream by a passing steamboat.[13]

In the aftermath of Hadnot's shooting, the white militia reacted with mass killing of the defenders. More than 40 times as many blacks died as did whites. The militia killed unarmed men trying to hide in the courthouse. They rode down and killed those attempting to flee. They dumped some bodies in the Red River. About 50 blacks survived the afternoon and were taken prisoner. Later that night they were killed by their captors. Only one man of the group, Levi Nelson, survived. He was shot by Cruikshank but managed to crawl away unnoticed. He later served as one of the Federal government's chief witnesses against those who were indicted for the attacks.[14]

Kellogg sent state militia colonels Theodore DeKlyne and William Wright to Colfax with warrants to arrest 50 white men and to install a new, compromise slate of parish officers. DeKlyne and Wright found the smoking ruins of the courthouse at Colfax, and many bodies of men who had been shot in the back of the head or the neck. One body was charred, another's head was beaten beyond recognition, and another had a slashed throat. Surviving blacks told DeKlyne and Wright that blacks dug a trench around the courthouse to protect it from what they saw as an attempt by white Democrats to steal an election. They were attacked by whites armed with rifles, revolvers and a small cannon. When blacks refused to leave, the courthouse was burned, and the black defenders were shot down. While the whites accused blacks of violating a flag of truce and rioting, black Republicans said that none of this was true. They accused whites of marching captured prisoners away in pairs and shooting them in the back of the head.[3]

On April 14 some of Governor Kellogg's new police force arrived from New Orleans. Several days later, two companies of Federal troops arrived. They searched for militia members, but many had already fled to Texas or the hills. The officers filed a military report in which they identified by name three whites and 105 blacks who had died, plus noted they had recovered 15-20 unidentified blacks from the river. They also noted the savage nature of many of the killings, suggesting an out-of-control situation.[15] The exact number of dead was never established.

The bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era, the Colfax massacre taught many lessons, including the lengths to which some opponents of Reconstruction would go to regain their accustomed authority. Among blacks in Louisiana, the incident was long remembered as proof that in any large confrontation, they stood at a fatal disadvantage. "The organization against them is too strong. ..." Louisiana black teacher and Reconstruction legislator John G. Lewis later remarked. "They attempted [armed self-defense] in Colfax. The result was that on Easter Sunday of 1873, when the sun went down that night, it went down on the corpses of two hundred and eighty negroes."[1]Aftermath

J.R. Beckwith, the US Attorney based in New Orleans, sent an urgent telegram about the massacre to the US Attorney General. The massacre in Colfax gained headlines from national newspapers from Boston to Chicago.[16] Various government forces spent weeks trying to round up members of the white militias. A total of 97 men were indicted. In the end, Beckwith charged nine men and brought them to trial for violations of the US Enforcement Act of 1870. It had been designed to provide Federal protection for civil rights of freedmen under the 14th Amendment against actions by terrorist groups such as the KKK.

The men were charged with one murder, and charges related to conspiracy against the rights of freedmen. There were two succeeding trials in 1874; in the first, one man was acquitted, while a mistrial was declared in the cases of the other eight. In the next trial, three men were found guilty of conspiracy against the freedmen's right of assembly and 15 other charges. Justice Joseph Bradley, an associate justice of the US Supreme Court happened to attend the trial. After the verdict was in, he ruled that the Enforcement Act was unconstitutional and ordered all the men set free.[17]

When the Federal government appealed the case, it was heard by the US Supreme Court as United States v. Cruikshank (1875). The Supreme Court ruled that the Enforcement Act of 1870 (which was based on the Bill of Rights and 14th Amendment) applied only to actions committed by the state, and that it did not apply to actions committed by individuals or private conspiracies. See, Morrison Remick Waite. This meant that the Federal government could not prosecute cases such as the Colfax killings. The court said plaintiffs who believed their rights abridged had to seek protection from the state. Louisiana did not prosecute any of the perpetrators of the Colfax massacre, and most southern states would not prosecute white men for attacks against freedmen.

The publicity about the Colfax massacre and Supreme Court ruling encouraged the growth of white paramilitary organizations. In May 1874 Nash formed the first chapter of the White League from his militia, and chapters soon sprang up in other areas of Louisiana, as well as the southern parts of nearby states. Unlike the KKK nightriders, they operated openly and often curried publicity. One historian described them as "the military arm of the Democratic Party."[18] Other paramilitary groups such as private militias and Red Shirts also arose, especially in South Carolina and Mississippi, which also had black majorities of population. There was little recourse for black American citizens in the South. Paramilitary groups used violence and murder to terrorize leaders among the freedmen and white Republicans, as well as to repress voting among freedmen during the 1870s.

In August 1874, for instance, the White League threw out Republican officeholders in Coushatta, Red River Parish, assassinating the six whites before they managed to leave, and killing five to 15 freedmen as witnesses. Four of the white men killed were related to the state representative from the area.[19] Such violence served to intimidate voters and officeholders. It was one of the methods white Democrats used to gain control in the 1876 elections and ultimately to dismantle Reconstruction in Louisiana.

In 1950, Louisiana erected a state highway marker noting the event of 1873 as "the Colfax Riot", as it was traditionally called in the white community. The marker states, "On this site occurred the Colfax Riot in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873 marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South."[20] [21]

Renewed attention

The Colfax Riot is among the events of Reconstruction and late 19th century history which has received new national attention, much as the 1923 riot in Rosewood, Florida did near the end of the 20th century. In 2007 and 2008 two new books[clarification needed] were published about the Colfax events. One especially addressed the political and legal implications of the Supreme Court case that arose out of prosecution of several men of the white militia. In addition, a film documentary is in preparation.

In 2007 the Red River Heritage Association, Inc. was formed, a group that intends to establish a museum in Colfax as a center for collecting materials and interpreting the history of Reconstruction in Louisiana and especially the Red River area.

In 2008, on the 135th anniversary of the Colfax Riot, an interracial group commemorated the event. They lay flowers where some victims had fallen.[22]

Notes

- ^ a b Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, p.437

- ^ Ulysses S. Grant, People and Events: "The Colfax Massacre", PBS Website, accessed 6 Apr 2008

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m The Day Freedom Died, Charles Lane, p. 265, a Holt Paperback, copyright 2008

- ^ Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. "Colfax Riot Historical Marker". http://www.stoppingpoints.com/louisiana/Grant/Colfax+Riot.html.

- ^ Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died, New York: Macmillan, 2009, p.13

- ^ a b Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, New York: Perennial Library edition, 1989, p.550

- ^ Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2008. pp. 54–56

- ^ James K. Hogue, "The Battle of Colfax: Paramilitarism and Counterrevolution in Louisiana", 2006, accessed 15 Aug 2008

- ^ Keith, LeeAnna (2007). The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & The Death of Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780195310269. http://books.google.com/?id=zEkQqruhR-sC&lpg=PA169&pg=PA100.

- ^ Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2008. p. 56

- ^ Keith, LeeAnna (2007). The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & The Death of Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 117. ISBN 9780195310269. http://books.google.com/?id=zEkQqruhR-sC&lpg=PA169&pg=PA117.

- ^ Lane, p. 57

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York: Farrar Strauss & Giroux, paperback, 2007, p.18

- ^ Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2008. p. 124

- ^ "Military Report on Colfax Riot, 1875", from the Congressional Record, accessed 6 Apr 2008

- ^ Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died, New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2008, p.22

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York; Farrar Strauss & Giroux, 2006, p.25

- ^ George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- ^ Eric Foner,Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, New York: Perennial Classics, 2002, p. 551

- ^ Keith, LeeAnna (2007). The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & The Death of Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 169. ISBN 9780195310269. http://books.google.com/?id=zEkQqruhR-sC&pg=PA169&lpg=PA169&dq=louisiana+highway+marker+colfax.

- ^ Rubin, Richard (July/August 2003). "The Colfax Riot". The Atlantic Monthly (The Atlantic Monthly) (July/August 2003). http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/2003/07/rubin.htm. Retrieved June 2009.

- ^ LeeAnna Keith, "History is a Gift: The Colfax Massacre", 17 Apr 2008, accessed 13 Aug 2008

See also

- List of massacres in Louisiana

References

- Foner, Eric, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, 1st ed., New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Goldman, Robert M., Reconstruction & Black Suffrage: Losing the Vote in Reese & Cruikshank, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001.

- Hogue, James K., Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battle and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

- Keith, Leeanna, The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & The Death of Reconstruction, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007

- KKK Hearings, 46th Congress, 2d Session, Senate Report 693.

- Lane, Charles, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2008.

- Lemann, Nicholas, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

- Rubin, Richard, "The Colfax Riot", The Atlantic, Jul/Aug 2003

- Taylor, Joe G., Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863-1877, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974, pp. 268–70.

External links

Categories:- 1873 in Louisiana

- 1873 riots

- History of Louisiana

- Reconstruction

- History of voting rights in the United States

- Political repression in the United States

- Racially motivated violence against African Americans

- History of African-American civil rights

- White supremacy in the United States

- Riots and civil disorder in the United States

- Massacres in the United States

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.