- Cherry Valley massacre

-

Cherry Valley Massacre Part of the American Revolutionary War

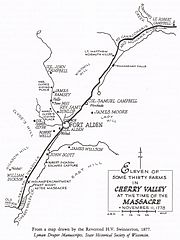

Cherry Valley massacre, the fate of Jane Wells, one of thirty non-combatants killed during the massacre.Date November 11, 1778 Location Cherry Valley, New York Result British victory Belligerents  United States

United States Great Britain

Great Britain

Seneca tribeCommanders and leaders Ichabod Alden †

William Stacy (POW)Walter Butler,

Cornplanter

Joseph Brant,

Little BeardStrength 7th Massachusetts Regiment

250 settlers and militia321 Brant's Volunteers and other Iroquois

150 Butler's Rangers,

50 8th Regiment of FootCasualties and losses 14 soldiers killed,

11 soldiers captured,

30 inhabitants killed,

34 inhabitants captured5 wounded The Cherry Valley Massacre was an attack by British and Seneca forces on a fort and the village of Cherry Valley in eastern New York on the cold, snowy and rainy morning[1] of November 11, 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. It has been described as one of the most horrific frontier massacres of the Revolution.[2] Fighting in and near the Mohawk Valley was fierce on both sides, and retaliation escalated.

The Seneca were angered over the burning of Tioga by forces under Colonel Thomas Hartley, his accusations of atrocities by the Iroquois at the Battle of Wyoming[3] and the colonists' recent destruction of their settlement of Onoquaga.

Contents

Massacre

Captain Walter Butler (the son of Colonel John Butler) led two companies of Butler's Rangers commanded by Captain John McDonell and Captain William Caldwell. There were also about 300 Seneca and 50 from the 8th Regiment of Foot. Cornplanter and the Mohawk chief Joseph Brant were the major Indian leaders. Brant's force of Brant's Volunteers was seriously reduced because of contention with Butler.

The fort, a palisade around the village meeting house, had a temporary garrison of 300 soldiers of the 7th Massachusetts Regiment of the Continental Army commanded by Col. Ichabod Alden. It could not be taken. As was usual, the officers of the regiment were quartered in private homes. The attackers killed at least sixteen officers and troops of the quarters guards, including Alden, while he was running from the Wells house to the fort.[4] Most accounts say Alden was within reach of the gates, only to stop and try to shoot his pursuer, perhaps Joseph Brant.[5][6] His wet pistol repeatedly misfired and he was killed by a thrown tomahawk hitting him in the forehead.[1] Lt. Col. William Stacy, second in command, also quartered at the Wells house, was taken prisoner.[1][4] Stacy's son Benjamin, and cousin Rufus Stacy, made the fort after running through a hail of bullets. Stacy's brother-in-law Gideon Day was killed.[7]

Lt. William McKendry, a quartermaster in Colonel Alden's regiment, kept a journal with firsthand accounts of the actions at Cherry Valley. McKendry's journal entry for November 11, 1778 described the attack:

Immediately came on 442 Indians from the Five Nations, 200 Tories under the command of one Col. Butler and Capt. Brant; attacked headquarters; killed Col. Alden; took Col. Stacy prisoner; attacked Fort Alden; after three hours retreated without success of taking the fort.[8][9]

McKendry identified the fatalities of the massacre as Colonel Alden, thirteen other soldiers, and thirty civilian inhabitants.

A newspaper article from the November 25, 1778 edition of the New Jersey Gazette reports "The enemy killed, scalped, and most barbarously murdered, thirty-two inhabitants, chiefly women and children, also Colonel Alden…" and "They committed the most inhuman barbarities on most of the dead" and "the lieutenant-colonel, all the officers and continental soldiers, were stripped and drove naked before them."[10] Several accounts indicate that during the fighting, or shortly thereafter, Col. Stacy was about to be killed, but Brant intervened. "I have often heard it asserted by the old residents of Cherry Valley, that he [Brant] saved the life of Lieut. Col Stacy, who was second in command of the fort, but being outside, was made prisoner when Col. Alden was killed. It is said Stacy was a freemason, and as such made an appeal to Brant, and was spared. Judge James S. Campbell, of Cherry Valley, who was then a child and a prisoner, informs me, that he recollects seeing Col. Stacy stripped of his clothing, as if about to be murdered, but his life was spared."[11] The aforementioned James Campbell, his siblings, and his mother were among the civilians taken prisoner and then adopted into various Mohawk families. James, the son of Col. Samuel Campbell of Cherry Valley who fought at the Battle of Oriskany, was held for over a year until freed during a prisoner exchange.[12]

Before the war, Brant had personal friendships with the prominent families in Cherry Valley, including members of the Wells, Campbell, Dunlop, and Clyde families, many of whom suffered terribly during the massacre.[6] Despite the efforts of Butler and Brant to stop it, more than thirty women and children and several Loyalist townspeople were killed and scalped.

Aftermath

Butler purchased the captured officers from the Indians and arranged for some of the women and children prisoners to be freed.

The Americans had the previous year decided to attack the Iroquois and their villages. Cherry Valley along with the accusations of murder of non-combatants at Wyoming, helped pave the way for the launch of the Sullivan Expedition, commissioned by commander-in-chief General George Washington and led by Major General John Sullivan, which destroyed over 40 Iroquois villages in their homelands of central and western New York. The 7th Massachusetts was attached to the New York Brigade of Brig-Gen James Clinton and participated in the expedition.

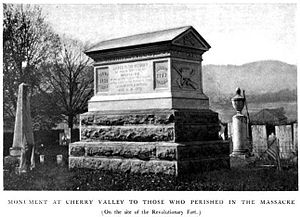

Memorial

A monument was dedicated at Cherry Valley on August 15, 1878, at the centennial anniversary of the massacre. Former New York Governor Horatio Seymour delivered a dedication address at the monument to an audience of about 10,000 persons, saying:

I am here today not only to show reverence for those dead patriots, but to offer my respects and heartfelt gratitude to the living descendants of those illustrious persons of the early settlements, who have erected this memorial stone. It is to be hoped that their example will be copied; that the report of these commemorative exercises will move others to like acts of pious duty. Let every son of this soil uncover reverently as this monument is unveiled, and do reverence to their sturdy patriotism, made strong by their grand faith, their trials, and their sufferings, and show that the blood of innocent children, of wives, of sisters, of mothers, and of brave men, was not shed in vain. Let us show the world that 100 years have added to the value of that noble sacrifice. Thus we shall leave this sacred spot better men and women, with a higher and nobler purpose of life than that which animated us when we entered this domain of the dead.[13]Years after the massacre, Benjamin Stacy's home village of New Salem, Massachusetts celebrated the annual Old Home Day holiday with a Benjamin Stacy footrace, honoring his escape at Cherry Valley.[7]

References

- ^ a b c Campbell, Annals of Tryon County, 110-11.

- ^ Murray, Smithsonian Q & A: The American Revolution, 64.

- ^ Graymont, The Iroquois in the American Revolution, 181.

- ^ a b Goodnough, The Cherry Valley Massacre, 6-9.

- ^ Sawyer and Little, Abstracts from History of Cherry Valley and The Story of the Massacre at Cherry Valley, 13.

- ^ a b Swinnerton, The Story of Cherry Valley.

- ^ a b Lemonds, Col. William Stacy, 21.

- ^ Young, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. II – Second Series, 1855–1886, 449-50.

- ^ Ketchum, History of Buffalo, 322. (Ketchum identifies that it was actually Captain Walter Butler, not Colonel John Butler, commanding the attack.)

- ^ Moore, Diary of the American Revolution, Vol II, 104-05.

- ^ Beardsley, Reminiscences, 463.

- ^ Sawyer and Little, Abstracts from History of Cherry Valley and The Story of the Massacre at Cherry Valley, 23-4.

- ^ "The Cherry Valley Massacre, Unveiling of the Monument to Those Who Fell on Nov. 11, 1778", The New York Times, August 16, 1878

Bibliography

- Barker, Joseph: Recollections of the First Settlement of Ohio, Marietta College, Marietta, Ohio (1958) p. 35; original manuscript written late in Joseph Barker's life, prior to his death in 1843.

- Beardsley, Levi: Reminiscences; Personal and Other Incidents; Early Settlement of Otsego County, Charles Vinten, New York (1852) p. 463.

- Campbell, William W.: Annals of Tryon County; or, the Border Warfare of New-York during the Revolution, J. & J. Harper, New York (1831) pp. 96–120. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Annals of Tryon County.

- Cruikshank, Ernest, Butler's Rangers and the Settlement of Niagara, 1893

- Drake, Francis S.: Memorials of the Society of Cincinnati of Massachusetts, Boston (1873) pp. 465–67.

- Edes, Richard S. and Darlington, William M.: Journal and Letters of Col. John May, Robert Clarke and Co, Cincinnati, Ohio (1873), pp. 70–1.

- Goodnough, David: The Cherry Valley Massacre, November 11, 1778, The Frontier Massacre that Shocked a Young Nation, Franklin Watts, New York (1968). LCCN 68-24489 (Though classified as a "juvenile" book, Goodnough's The Cherry Valley Massacre is an excellent, thorough yet concise, account of the historical lead-up, the massacre, and aftermath.)

- Graymont, Barbara, The Iroquois in the American Revolution, 1972, ISBN 0-8156-0083-6

- Ketchum, William: An Authentic and Comprehensive History of Buffalo, with some account of Its Early Inhabitants both Savage and Civilized, Rockwell, Baker, and Hill, Buffalo, New York (1864) p. 322.

- Lemonds, Leo L.: Col. William Stacy – Revolutionary War Hero, Cornhusker Press, Hastings, Nebraska (1993) pp. 17–25.

- Moore, Frank: Diary of the American Revolution from Newspapers and Original Documents, Vol II, Charles Scribner, New York (1860), pp. 104–05.

- Murray, Stuart A. P.: Smithsonian Q & A: The American Revolution, HarperCollins Publishers by Hydra Publishing, New York (2006) p. 64.

- Sawyer, John: History of Cherry Valley from 1740 to 1898, Gazette Print, Cherry Valley, New York (1898), pp. 14–41.

- Sawyer, John and Little, Mrs. William: Abstracts from History of Cherry Valley and The Story of the Massacre at Cherry Valley, reprint containing abstracts of Sawyer's 1898 book and Little's 1890 paper, Heritage Books, Westminster, Maryland (2007). ISBN 1-58549-669-3

- Swinnerton, Henry: The Story of Cherry Valley, paper presented to the New York State Historical Association 1906, Cherry Valley, New York (1906?).

- "The Cherry Valley Massacre, Unveiling of the Monument to Those Who Fell on Nov. 11, 1778", The New York Times newspaper, New York, New York (August 16, 1878).

- Williams, Glenn F. Year of the Hangman: George Washington's Campaign Against the Iroquois, Westholme Publishing (2005). ISBN 1-59416-013-9

- Young, Edward J.: Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. II – Second Series, 1855-1886, University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1886) section entitled Journal of William McKendry, pg 436-478. This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at Young (1886).

External links

- Sullivanclinton.com - historic context

- Town of Cherry Valley, Historian's website

- Photos of the Cherry Valley monument

- Cherry Valley KIA & POW

- Maine Men serving in Col. Alden's Regiment

- Cherry Valley survivor Captain Holden

Categories:- 1778 in New York

- Battles of the American Revolutionary War

- Conflicts in 1778

- Massacres by Native Americans

- New York in the American Revolution

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.