- Greater Bulldog Bat

-

Greater Bulldog Bat

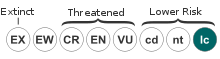

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Chiroptera Family: Noctilionidae Genus: Noctilio Species: N. leporinus Binomial name Noctilio leporinus

(Linnaeus, 1758)The greater bulldog bat or fisherman bat (Noctilio leporinus) is a type of fishing bat native to Latin America. The bat uses echolocation to detect water ripples made by the fish upon which it preys, then uses the pouch between its legs to scoop the fish up and its sharp claws to catch and cling to it. It is not to be confused with the lesser bulldog bat, which, though belonging to the same genus, merely catches water insects, such as water striders and water beetles.

It emits echolocation sounds through the mouth like Myotis daubentoni, but the sounds are quite different, containing a long constant frequency part around 55 kHz, which is an unusually high frequency for a bat this large.

Contents

General description

The greater bulldog bat is a large bat, often with a combined body and head length of 1.9 to 12.7 cm (4.6 to 5 in). It generally weighs from 50–90 grams. [2] Males tend to be larger than females, with the former averaging 67 grams and the latter averaging 56 grams.[3] They also differ in fur color. Males have bright orange fur on the back while females are dull gray.[4] However, both sexes have pale undersides and may have a pale mid-dorsal line.[4] The bulldog bat has tubular nostrils that open forward and down. It has slender, long, pointed ears with a tragus that has a notched outer edge. The bulldog bat has smooth lips but its upper lip is divided by a fold of skin while its bottom lip has a wart, under which are semicircular folds of skin that extend to the chin.[4] It is these features that give the bulldog bat gets name, as it resembles a bulldog.

The bulldog bat has a wingspan of 1 meter (3 feet). The wing of the bat is more than two and a half times the length of the head and body with nearly 65% of its wingspan being its third digit.[5] Its wings are long and narrow and it flies in a stiff-winged fashion. The bat’s wing beat is slow and deliberate. [5] Like most bats, the bulldog bat has a positive allometric relationship for flight musculature and body mass.[6] The bat is a capable swimmer and will use its wings like an oar.[4] The Greater Bulldog bat also has well-developed cheek pouches are used for storing food when foraging, particularly fish. [5] Its hind legs and feet are particularly large.[4]

Distribution and variation

The greater bulldog bat ranges from western (Sinaloa) and eastern (Veracruz) Mexico southward to northern Argentina. It also lives on most Caribbean islands. [5] While vast, it’s range is also discontinuous as the bat is restricted to mostly non-arid lowland and coastal areas and major river basin like the Amazon and Parana. There is geographical variation in the species and are classified as subspecies. In the rim of the Caribbean Basin, bats are large and usually have the pale mid-dorsal stripe, despite being variable in color.[7] These bats are known as N. l. mastivus. In Guianas and the Amazon Basin, the bats are small and dark and often lack the pale mid-dorsal stripe. [7] These bats are known as N. l. leporinus. In eastern Bolivia and the drainage basin of the Río Paraná south of the Brazilian Highlands and north of latitude 30° S, bats tend to be large and pale, more so than the other subspecies.[7] They are known as N. l. rufescens.

Ecology and behavior

The greater bulldog bat lives primarily in tropical lowland habitats.[8] The bats are commonly found over ponds and streams. They also found above estuaries of major rivers and bays and lagoons along coastlines.[9] They live in colonies that number in the hundreds. [5] In Trinidad, bulldog bats frequent hollow trees including silk-cotton, red mangrove and balatá.[10] The bats live in hollow tree roosts in other areas as well.[5] They also use deep sea caves for roosting.[10] Like most bats, bulldog bats are nocturnal.

Female bulldog bats stay together in groups while roosting and tend to be accompanied by a resident male. Females associate with the same individuals in the same location for several years unaffected by changes in resident males and movements of the group to different roosts.[11] A male may reside with a female group for two or more reproductive seasons.[11] Bachelor males roost either solitarily or in small groups away from the females. Female bats forage either solitarily or in small groups with their roost mates, with stable female groups returning to the same foraging areas over long time periods.[11] Males forage solitarily and use areas that are larger and different from those used by the females.[11]

Food and hunting

The greater bulldog bat is one of the few bat species that has adapted to eating fish. Nevertheless, the bats eat both fish and insects. During the wet season, the bats feed primarily on insects like moths and beetles.[2] During the dry season, bat will primarily feed on fish as well as crabs, scorpions and shrimp to a lesser extent.[2] The bulldog bat mostly forages for fish during high tide and locates them with echolocation. A bulldog bat will perform circular high flight searches. A bat doing a high search flight will make "pointed dips" at the spot where a fish has made a jump. When it descends to the water surface the echolocation signals of the bat decrease in pulse duration and interval which is typical of all bats.[12]

During low search flights, bulldog bats will rapidly snap the feet into the water at a spot where it has found a jumping fish or disturbance.[12] The bat will drop to the water surface, lowering its feet and and then drag its claws through the water in relatively straight lines for up to 10 m. When raking, the bat uses two strategies. In directed random rakes it rakes through patches of water with high activity of fish jumping.[12] With memory-directed random rakes, when there is no jumping fish, it will make very long rakes in areas where it has successfully made a catch before after flying for several minutes without any dips.[12]

Echolocation

Greater bulldog bats emit echolocation signals that are either at constant frequency (CF), frequency-modulated (FM) or a combination of the two (CF-FM).[12] The longest signals are the pure CF signal which have average duration of 13.3 ms and a maximum of 17 ms.[12] CF-FM signal involve a CF component followed by a FM component. The CF component of the CF-FM signals average 8.9 ms while the FM sweeps 3.9 ms. The CF components have frequencies of 52.8–56.2 kHz with the FM components have average bandwidths of 25.9 kHz.[12] Bulldog bats have two kinds of signal when flying. In one, the CF pulses begin at 60kHz and may drop in frequency but never below 50kHz. [5] The second type involves CF beginning at about 60kHz and drops in frequency by more than one octave.[5]

Reproduction cycle

For females, pregnancy occurs from September until January, and lactation starts in November and continues until April.[4] Female bulldog bats give birth to single young each pregnancy.[5] Male bats reproductive pattern with breeding mainly occurring in autumn and winter.[5] Young bats do not leave the roost to attempt to make sustained flight until they reach adult size, which is around one month.[5] There may be a high degree of parental care in this species and both adult males and female stay in the roost with the young during this time.[5]

Status

There are no major threats throughout its range. The bat is killed by Guatemala fish farmers.[1] It is also threatened by water pollution and in Belize; the water level has changed and restricted the range.[1] It is also threated by Deforestation.

References

- ^ a b c Barquez, R., Perez, S., Miller, B. & Diaz, M. 2008. Noctilio leporinus. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is low risk.

- ^ a b c Brooke, A. (1994) Diet of the Fishing Bat, Noctilio Leporinus (Chiroptera: Noctilionidae). Journal of Mammalogy. 75: 212-219.

- ^ Eisenburg, J. (1989) Mammals of the Neotropics. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b c d e f Nowak, R. (1999) Bulldog Bats, or Fisherman Bats. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 6ed: 347-349.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hood, C. S and Jones, J. K (1984) Noctilio leporinus. Mammalian Species. 216:1-7.

- ^ Strickler, T.L., (1978) "Allometric relationships among the shoulder muscles in the Chiroptera", Journal of Mammalogy, 59(1): 36-45.

- ^ a b c Davis, William B. (1973) "Geographic Variation in the Fishing Bat, Noctilio leporinus", Journal of Mammalogy, 54(4): 862-874.

- ^ Larry C. Watkins, J. Knox Jones, Hugh H. Genoways, (1972) Bats of Jalisco Mexico, Museum of Texas Tech Univ, 1:1-44. ISBN: 9780896720268

- ^ Smith, J. D., H. H. Genoways. (1974) "Bats of Margarita Island, Venezuela, with zoogeographic comments", Bulletin of Southern California Academy of Sciences, 73:64-79.

- ^ a b C.G. Goodwin and A. Greenhall, (1961) "A review of the bats of Trinidad and Tobago", Bull. Am. Mus. nat. Hist. 122:187–302.

- ^ a b c d Brooke, A. May (1997) "Organization and Foraging Behaviour of the Fishing Bat, Noctilio leporinus (Chiroptera:Noctilionidae)". Ethology, 103:(5): 421-436.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hans-Ulrich Schnitzler, Elisabeth K. V. Kalko, Ingrid Kaipf and Alan D. Grinnell. (1994) "Fishing and Echolocation Behavior of the Greater Bulldog Bat, Noctilio leporinus, in the Field", Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 35(5): 327-345.

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Bats of South America

- Mammals of Brazil

- Mammals of Guyana

- Noctilionidae

- Mammals of Costa Rica

- Animals described in 1758

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.