- 30 September Movement

-

This article is part of the

History of Indonesia series

See also:

Timeline of Indonesian History Prehistory Early kingdoms Kutai (4th century) Tarumanagara (358–669) Kalingga (6th–7th century) Srivijaya (7th–13th centuries) Sailendra (8th–9th centuries) Sunda Kingdom (669–1579) Medang Kingdom (752–1045) Kediri (1045–1221) Singhasari (1222–1292) Majapahit (1293–1500) The rise of Muslim states Spread of Islam (1200–1600) Sultanate of Ternate (1257–present) Malacca Sultanate (1400–1511) Sultanate of Demak (1475–1548) Aceh Sultanate (1496–1903) Sultanate of Banten (1526–1813) Mataram Sultanate (1500s–1700s) European colonization The Portuguese (1512–1850) Dutch East India Co. (1602–1800) Dutch East Indies (1800–1942) The emergence of Indonesia National awakening (1908–1942) Japanese occupation (1942–45) National revolution (1945–50) Independent Indonesia Liberal democracy (1950–57) Guided Democracy (1957–65) Start of the New Order (1965–66) The New Order (1966–98) Reformasi era (1998–present) The Thirtieth of September Movement (Indonesian: Gerakan 30 September, abbreviated as G30S, also called Gestok (Gerakan 1 Oktober, First of October Movement)) was a self-proclaimed organization of Indonesian National Armed Forces members who, in the early hours of 1 October 1965, assassinated six Indonesian Army generals in an abortive coup d'état.[1] Later that morning, the organization declared that it was in control of media and communication outlets and had taken President Sukarno under its protection. By the end of the day, the coup attempt had failed in Jakarta at least. Meanwhile in central Java there was an attempt to take control over an army division and several cities. By the time this rebellion was put down, two more senior officers were dead.

In the days and weeks that followed, the army blamed the coup attempt on the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). Soon a campaign of mass killing was underway, which resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands of alleged communists.

The group's name was more commonly abbreviated "G30S/PKI" by those wanting to associate it with the PKI, and propaganda would refer to the group as Gestapu (for its similarity to "Gestapo", the name of the Nazi secret police).[2]

Contents

Kidnappings of generals

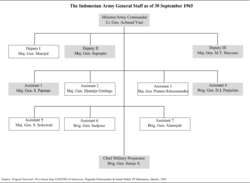

The Army General Staff at the time of the coup attempt. The generals who were killed are shown in grey.[3]

The Army General Staff at the time of the coup attempt. The generals who were killed are shown in grey.[3]

At around 3:15 A.M. on 1 October, seven groups of troops in trucks and buses comprising soldiers from the Tjakrabirawa (Presidential Guard) the Diponegoro (Central Java) and Brawijaya (East Java) Divisions, left the movement's base at Halim Perdanakusumah Air Force Base, just south of Jakarta to kidnap seven generals, all members of the Army General Staff.[4][5] Three of the intended victims, (Minister/Commander of the Army Lieutenant General Ahmad Yani, Major General M. T. Haryono and Brigadier General D.I. Panjaitan) were killed at their homes, while three more (Major General Soeprapto, Major General S. Parman and Brigadier General Sutoyo) were taken alive. Meanwhile, the main target, Coordinating Minister for Defense and Security and Armed Forces Chief of Staff, General Abdul Harris Nasution managed to escape the kidnap attempt by jumping over a wall into the Iraqi embassy garden, but his personal aide, First Lieutenant Pierre Tendean, was captured by mistake after being mistaken for Nasution in the dark.[4][6] Nasution's five-year old daughter, Ade Irma Suryani Nasution, was shot and died on 6 October.[7] The generals and the bodies of their dead colleagues were taken to a place known as Lubang Buaya near Halim where those still alive were shot, and the bodies of all the victims were thrown down a disused well.[4][8][9]

Takeover in Jakarta

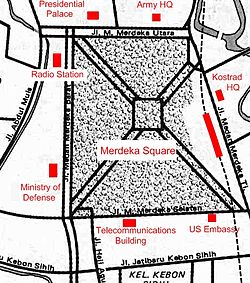

Later that morning, around 2,000 troops from two Java-based divisions (Battalion 454 from the Diponegoro Division and Battalion 530 from the Siliwangi Division) occupied what is now Lapangan Merdeka, the park around the National Monument in central Jakarta, and three sides of the square, including the RRI (Radio Republik Indonesia) building. They did not occupy the east side of the square – location of the armed forces strategic reserve (KOSTRAD) headquarters, commanded at the time by Major General Suharto. At some time during the night, D.N. Aidit, the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) leader and Air Vice-Marshal Omar Dhani, the Air Force commander both went to Halim.

Following the news at 7AM, RRI broadcast a message from Lieutenant-Colonel Untung Syamsuri, commander of Cakrabirawa, Presidential guard, to the effect that the 30 September Movement, an internal army organization, had taken control of strategic locations in Jakarta, with the help of other military units . This was to forestall a coup attempt by a 'General's Council' aided by the Central Intelligence Agency, intent on removing Sukarno on 5 October, "Army Day".[10] It was also stated that President Sukarno was under the movement's protection. He traveled to Halim after learning that there were troops near the Palace on the north side of Lapangan Merdeka. Sukarno later claimed this was so he could be near an aircraft should he need to leave Jakarta. Further radio announcements later that day listed 45 members of the G30S Movement and stated that all army ranks above Lieutenant Colonel would be abolished.[11][12]

The end of the movement in Jakarta

At 5.30AM, Suharto was woken up by his neighbor [13] and told of the disappearances of the generals and the shootings at their homes. He went to KOSTRAD HQ and tried to contact other senior officers. He managed to contact the Naval and Police commanders, but was unable to contact the Air Force Commander. He then took command of the Army and issued orders confining all troops to barracks.

Because of poor planning, the coup leaders had failed to provide provisions for the troops on Lapangan Merdeka, who were becoming hot and thirsty. They were under the impression that they were guarding the president in the palace. Over the course of the afternoon, Suharto persuaded both battalions to give up without a fight, first the Brawijaya troops, who came to Kostrad HQ, then the Diponegoro troops, who withdrew to Halim. His troops gave Untung's forces inside the radio station an ultimatum and they also withdrew. By 7PM Suharto was in control of all the installations previously held by the 30 September Movement's forces. Now joined by Nasution, at 9PM he announced over the radio that he was now in command of the Army and that he would destroy the counter-revolutionary forces and save Sukarno. He then issued another ultimatum, this time to the troops at Halim. Later that evening, Sukarno left Halim and arrived in Bogor, where there was another presidential palace.[14][15]

Most of the rebel troops fled, and after a minor battle in the early hours of 2 October, the Army regained control of Halim, Aidit flew to Yogyakarta and Dani to Madiun before the soldiers arrived.[15]

Events in Central Java

Following the 7AM radio broadcast, troops from the Diponegoro Division in Central Java took control of five of the seven divisions in the name of the 30 September movement .[16] The PKI mayor of Solo issued a statement in support of the movement. Rebel troops in Yogyakarta, led by Major Muljono, kidnapped and later killed Col. Katamso and his chief of staff Lt. Col. Sugijono. However, once news of the movement's failure in Jakarta became known, most of its followers in Central Java gave themselves up.[15]

Anti-communist purge

Suharto and his associates immediately blamed the PKI as masterminds of the 30 September Movement. With the support of the Army, and fueled by horrific tales of the alleged torture and mutilation of the generals at Lubang Buaya, anti-PKI demonstrations and then violence soon broke out. Violent mass action started in Aceh, then shifted to Central and East Java.[17] (see Indonesian killings of 1965–66) Suharto then sent the RPKAD paratroops under Col. Sarwo Edhie to Central Java. When they arrived in Semarang, locals burned the PKI headquarters to the ground.[18] The army swept through the countryside and were aided by locals in killing suspected communists. In East Java, members of Ansor, the youth wing of the Nahdlatul Ulama went on a killing frenzy, and the slaughter later spread to Bali. Figures given for the number of people killed across Indonesia vary from 78,000 to one million.[19] Among the dead was Aidit, who was captured by the Army on 25 November and summarily executed shortly after.[20][21]

Theories about the 30 September Movement

A PKI coup attempt: The "official" (New Order) version

The Army leadership began making accusations of PKI involvement at an early stage. Later, the government of President Suharto would reinforce this impression by referring to the movement using the abbreviation "G30S/PKI". School textbooks followed the official government line[22] that the PKI, worried about Sukarno's health and concerned about their position should he die, acted to seize power and establish a communist state. The trials of key conspirators were used as evidence to support this view, as was the publication of a cartoon supporting the 30 September Movement in the 2 October issue of the PKI magazine Harian Rakyat (People's Daily). According to later pronouncements by the army, the PKI manipulated gullible left-wing officers such as Untung through a mysterious "special bureau" that reported only to the party secretary, Aidit. This case relied on a confession by the alleged head of the bureau, named Sjam, during a staged trial in 1967. But it was never convincingly proved to Western academic specialists, and has been challenged by some Indonesian accounts.[23]

The plotters

The reason given by those involved in the 30 September movement was that it was to prevent a planned seizure of power by a "Council of Generals" (Dewan Jenderal). They claimed to be acting to save Sukarno from these officers allegedly led by Nasution and including Yani, who had planned a coup on Armed Forces Day – 5 October.

Internal army affair

In 1971, Benedict Anderson and Ruth McVey wrote an article which came to be known as the Cornell Paper. In the essay they proposed that the 30 September Movement was indeed entirely an internal army affair as the PKI had claimed. They claimed that the action was a result of dissatisfaction on the part of junior officers who found it extremely difficult to obtain promotions and because of hostility toward the generals because of their corrupt and decadent lifestyles. They allege that the PKI was deliberately involved by, for example, bringing Aidit to Halim: a diversion from the embarrassing fact the Army was behind the movement.

Recently Anderson expanded on his theory that the coup attempt was almost totally an internal matter of a divided military with the PKI playing only a peripheral role; that the right-wing generals assassinated on 1 October 1965 were, in fact, the Council of Generals coup planning to assassinate Sukarno and install themselves as a military junta. Anderson argues that G30S was indeed a movement of officers loyal to Sukarno who carried out their plan believing it would preserve, not overthrow, Sukarno's rule. The boldest claim in the Anderson theory, however, is that Suharto was in fact privy to the G30S assassination plot.

Central to the Anderson theory is an examination of a little-known figure in the Indonesian army, Colonel Abdul Latief. Latief had spent a career in the Army and, according to Anderson, had been both a staunch Sukarno loyalist and a friend with Suharto. Following the coup attempt, however, Latief was jailed and named a conspirator in G30S. At his military trial in the 1970s, Latief made the accusation that Suharto himself had been a co-conspirator in the G30S plot, and had betrayed the group for his own purposes.

Anderson points out that Suharto himself has twice admitted to meeting Latief in a hospital on the 30 September 1965 (i.e. G30S) and that his two narratives of the meeting are contradictory. In an interview with American journalist Arnold Brackman, Suharto stated that Latief had been there merely "to check" on him, as his son was receiving care for a burn. In a later interview with Der Spiegel, Suharto stated that Latief had gone to the hospital in an attempt on his life, but had lost his nerve. Anderson believes that in the first account, Suharto was simply being disingenuous; in the second, that he had lied.

Further backing his claim, Anderson cites circumstantial evidence that Suharto was indeed in on the plot. Among these are:

- That almost all the key military participants named a part of G30S were, either at the time of the assassinations or just previously, close subordinates of Suharto: Lieutenant-Colonel Untung, Colonel Latief, and Brigadier-General Supardjo in Jakarta, and Colonel Suherman, Major Usman, and their associates at the Diponegoro Division’s HQ in Semarang.

- That in the case of Untung and Latief, their association with Suharto was so close that attended each others' family events and celebrated their sons' rites of passage together.

- That the two generals who had direct command of all troops in Jakarta (save for the Presidential Guard, who carried out the assassinations) were Suharto and Jakarta Military Territory Commander Umar Wirahadikusumah. Neither of these figures were assassinated, and (if Anderson's theory that Suharto lied about an attempt on his life by Latief) no attempt was even made.

- That during the time period in which the assassination plot was organized, Suharto (as commander of Kostrad) had made a habit of acting in a duplicitous manner: while Suharto was privy to command decisions in Confrontation, the intelligence chief of his unit Ali Murtopo had been making connections and providing information to the hostile governments of Malaysia, Singapore, United Kingdom, and the United States through an espionage operation run by Benny Moerdani in Thailand. Murdani later became a spy chief in Suharto's government.

Anderson's theory, for all the exhaustive research it has entailed, still leaves open a number of questions of interpretation. If, as Anderson believes, Suharto did have inside knowledge of the G30S plot, this still leaves open several possibilities: (1) that Suharto had truly taken part in the plot and defected; (2) that he had been acting as a spy for the Council of Generals; or (3) that he was uninterested completely in the factional struggle of G30S and Council of Generals. Given that Suharto has since died these questions are unlikely to be answered easily.

Suharto with CIA support

Professor Dale Scott alleges that the entire movement was designed to allow for Suharto's response. He draws attention to the fact the side of Lapangan Merdeka on which KOSTRAD was situated was not occupied, and that only those generals who might have prevented Suharto seizing power (except Nasution) were kidnapped. He also alleges that the fact that the generals were killed near an air force base where PKI members had been trained allowed him to shift the blame away from the Army. He links the support given by the CIA to anti-Sukarno rebels in the 1950s to their later support for Suharto and anti-communist forces. He points out that training in the US of Indonesian Army personnel continued even as overt military assistance dried up. Another damaging revelation came to light when it emerged that one of the main plotters, Col Latief, was a close associate of Suharto, as were other key figures in the movement, and that Latief actually visited Suharto on the night before the murders (Wertheim, 1970)

British psyops

The role of the United Kingdom's Foreign Office and MI6 intelligence service has also come to light, in a series of exposés by Paul Lashmar and Oliver James in The Independent newspaper beginning in 1997. These revelations have also come to light in journals on military and intelligence history.

The revelations included an anonymous Foreign Office source stating that the decision to unseat Pres. Sukarno was made by Prime Minister Harold Macmillan then executed under Prime Minister Harold Wilson. According to the exposés, the United Kingdom had already become alarmed with the announcement of the Konfrontasi policy. It has been claimed that a CIA memorandum of 1962 indicated that Prime Minister Macmillan and President John F. Kennedy were increasingly alarmed by the possibility of the Confrontation with Malaysia spreading, and agreed to "liquidate President Sukarno, depending on the situation and available opportunities." However, the documentary evidence does not support this claim.

To weaken the regime, the Foreign Office's Information Research Department (IRD) coordinated psychological operations in concert with the British military, to spread black propaganda casting the PKI, Chinese Indonesians, and Sukarno in a bad light. These efforts were to duplicate the successes of British Psyop campaign in the Malayan Emergency.

Of note, these efforts were coordinated from the British High Commission in Singapore where the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Associated Press (AP), and New York Times filed their reports on the Indonesian turmoil. According to Roland Challis, the BBC correspondent who was in Singapore at the time, journalists were open to manipulation by IRD because of Sukarno's stubborn refusal to allow them into the country: "In a curious way, by keeping correspondents out of the country Sukarno made them the victims of official channels, because almost the only information you could get was from the British ambassador in Jakarta."

These manipulations included the BBC reporting that Communists were planning to slaughter the citizens of Jakarta. The accusation was based solely on a forgery planted by Norman Reddaway, a propaganda expert with the IRD. He later bragged in a letter to the British ambassador in Jakarta, Sir Andrew Gilchrist that it "went all over the world and back again," and was "put almost instantly back into Indonesia via the BBC." Sir Andrew Gilchrist himself informed the Foreign Office on 5 October 1965: "I have never concealed from you my belief that a little shooting in Indonesia would be an essential preliminary to effective change."

In the 16 April 2000 Independent, Sir Denis Healey, Secretary of State for Defence at the time of the war, confirmed that the IRD was active during this time. He officially denied any role by MI6, and denied "personal knowledge" of the British arming the right-wing faction of the Army, though he did comment that if there were such a plan, he "would certainly have supported it."

Although the British MI6 is strongly implicated in this scheme by the use of the Information Research Department (seen as an MI6 office), any role by MI6 itself is officially denied by the UK government, and papers relating to it have yet to be declassified by the Cabinet Office. (The Independent, 6 December 2000)

Sukarno's plot

In a book first published in India in 2005, which draws extensively on the evidence presented at the trials of the conspirators, Victor Fic claims that Aidit and the PKI decided to mount a preemptive strike against the senior army generals to forestall an army takeover. He alleges that Sukarno had met with representatives of the Chinese government and had agreed to retire in exile in China. Following the purge of the generals, the president would appoint a Mutual Cooperation (Gotong Royong) cabinet and then retire on grounds of ill-health. Should he not agree to do so, he would be "dispatched" under the protection of the PKI.

Incompetent plotters; the army takes advantage

In a 2007 book on the 30 September Movement, Professor John Roosa dismisses the official version of events, saying it was "imposed by force of arms" and "partly based on black propaganda and torture-induced confessions." He points out that Suharto never satisfactorily explained away the fact that most of the movement's protagonists were Army officers. However, he does concede that some elements of the PKI were involved.[24]

Similarly, he asks why, if the movement was planned by military officers, as alleged in the "Cornell Paper", was it so poorly planned. In any case, he says, the movement's leaders were too disparate a group to find enough common ground to carry out the operation.[25]

He claims that US officials and certain Indonesian Army officers had already outlined a plan in which the PKI would be blamed for an attempted coup, allowing for the party's suppression and the installation of a military regime under Sukarno as a figurehead president.Once the 30 September Movement acted, the US gave the Indonesian military encouragement and assistance in the destruction of the PKI, including supplying lists of party members and radio equipment.[26]

As to the movement itself, Roosa concludes that it was led by Sjam, in collaboration with Aidit, but not the party as a whole, together with Pono, Untung and Latief.[27] Suharto was able to defeat the movement because of he knew of it beforehand and because the Army had already prepared for such a contingency. He says Sjam was the link between the PKI members and the Army officers, but that the fact there was no proper coordination was a major reason for the failure of the movement as a whole.[28]

Blamed people

Name Birth and Death dates Position or context Colonel Abdul Latief 27 July 1926 – 6 April 2005 Commander, 1st Battalion, 5th (Jaya) Military Area Command. Dipa Nusantara Aidit 30 July 1923 – 25 November 1965 Chairman of the PKI Brig. Gen. Mustafa Sjarif Supardjo 23 March 1923 – Commander 4th Combat Command, West Kalimantan Kamaruzaman Sjam 30 April 1924–1986 Special Bureau Lt. Col. Untung Syamsuri 3 July 1926 – September 1967 Commander 1st Battalion Tjakrabirawa. Flight Maj. Soejono 1920– Commander of the guard at Halim Airforce Base Pono (Supono Marsudidjojo) September 1919 – PKI member and member of the Special Bureau[30] Footnotes

- ^ "The assassination of generals on the morning of 1 October was not really a coup attempt against the government, but the event has been almost universally described as an 'abortive coup attempt,' so I have continued to use the term." Crouch 1978, p. 101

- ^ Roosa (2007) p29

- ^ Nugroho Notosusanto & Ismail Saleh (1968) Appendix B, p248

- ^ a b c Anderson & McVey (1971)

- ^ a b Roosa (2007) p36

- ^ Roosa (2007) p40

- ^ Ricklefs (1991), p. 281.

- ^ Ricklefs (1982) p269

- ^ Sekretariat Negara Republik Indonesia (1994) p103

- ^ Roosa (2007) p35

- ^ Ricklefs (1982) p269–270

- ^ Sekretariat Negara Republik Indonesia (1994) Appendix p13

- ^ Sundhaussen (1982) p207

- ^ Roosa (2007) p59

- ^ a b c Ricklefs (1982) p270

- ^ Sundhausen, 1981

- ^ Sundhaussen (1982) p215–216

- ^ Hughes (2002)p160

- ^ Sundhaussen (1982) p218

- ^ Sundhaussen (1982) p217

- ^ Roosa (2007) p69

- ^ Rafadi & Latuconsina, 1997

- ^ McDonald, Hamish (28 January 2008), "No End to Ambition", Sydney Morning Herald, http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/no-end-to-ambition/2008/01/27/1201368944638.html

- ^ Roosa (2007) p65

- ^ Roosa (2007) p72

- ^ Roosa (2007) pp193–195

- ^ Roosa (2007) p204

- ^ Roosa (2007) pp216–220

- ^ Roosa (2007) p137

- ^ Roosa (2007) p150

References

Primary sources

- "Selected Documents Relating to the 30 September Movement and Its Epilogue", Indonesia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Modern Indonesia Project) 1: 131–205, April 1966, doi:10.2307/3350789, JSTOR 3350789, http://cip.cornell.edu/seap.indo/1107134819, retrieved 20 September 2009

Secondary sources

- Anderson, Benedict R. & McVey, Ruth T. (1971), A Preliminary Analysis of the 1 October 1965, Coup in Indonesia, Interim Reports Series, Ithaca, NY: Cornell Modern Indonesia Project, OCLC 210798

- Anderson, Benedict (May 2000), "Petrus Dadi Ratu", New Left Review (London) 3: 7–15, http://newleftreview.org/A2242, retrieved 18 September 2009

- Crouch, Harold (April 1973), "Another Look at the Indonesian "Coup"", Indonesia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Modern Indonesia Project) 15: 1–20, doi:10.2307/3350791, JSTOR 3350791, http://cip.cornell.edu/seap.indo/1107128617, retrieved 18 September 2009

- Crouch, Harold (1978), The Army and Politics in Indonesia, Politics and International Relations of Southeast Asia, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, ISBN 0801411556

- Fic, Victor M. (2005). Anatomy of the Jakarta Coup: 1 October 1965: The Collusion with China which destroyed the Army Command, President Sukarno and the Communist Party of Indonesia. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia. ISBN 978-979-461-554-6

- Hughes, John (2002), The End of Sukarno – A Coup that Misfired: A Purge that Ran Wild, Archipelago Press, ISBN 981-4068-65-9

- Lashmar, Paul and Oliver, James. "MI6 Spread Lies To Put Killer In Power" The Independent. (16 April 2000)

- Lashmar, Paul and Oliver, James. "How we destroyed Sukarno" The Independent. (6 December 2000)

- Lashmar, Paul; Oliver, James (1999), Britain's Secret Propaganda War, Sutton Pub Ltd, ISBN 0-7509-1668-0

- Nugroho Notosusanto & Ismail Saleh (1968) The Coup Attempt of the "30 September Movement" in Indonesia, P.T. Pembimbing Masa-Djakarta.

- Rafadi, Dedi & Latuconsina, Hudaya (1997) Pelajaran Sejarah untuk SMU Kelas 3 (History for 3rd Grade High School), Erlangga Jakarta. ISBN 979-411-252-6

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1982) A History of Modern Indonesia", MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-24380-3

- Roosa, John (2006). Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement & Suharto's Coup D'État in Indonesia. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-22034-1

- Scott, Peter Dale (1985) The United States and the Overthrow of Sukarno Pacific Affairs 58, pp 239–164

- Sekretariat Negara Republik Indonesia (1975) 30 Tahun Indonesia Merdeka: Jilid 3 (1965–1973) (30 Years of Indonesian Independence: Volume 3 (1965–1973)

- Sekretariat Negara Republik Indonesia (1994) Gerakan 30 September Pemberontakan Partai Komunis Indonesia: Latar Belakang, Aksi dan Penumpasannya (The 30 September Movement/Communist Party of Indoneisa: Bankgrounds, Actions and its Annihilation) ISBN 9790830025

- Sundhaussen, Ulf (1982) The Road to Power: Indonesian Military Politics 1945-1967, Oxford University Press. ISBN 019 582521-7

- Wertheim, W.F. (1970) Suharto and the Untung Coup – the Missing Link", Journal of Contemporary Asia I No. 1 pp 50–57

External links

- United States Department of State documents on U.S. Foreign Relations, 1964–1968: Indonesia

- Coup and Counter Reaction, October 1965 – March 1966: Documents 142–164

- Coup and Counter Reaction, October 1965 – March 1966: Documents 165–183

- Coup and Counter Reaction, October 1965 – March 1966: Documents 184–205

Categories:- Transition to the New Order

- Attempted coups

- Cold War conflicts

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.