- Memín Pinguín

-

Memín Pinguín is a fictional character from Mexico. Stories featuring him, a very poor Cuban Mexican boy, first appeared in the 1940s and have remained in print since.

The character is known as Memín Pingüín by some Mexicans due to a publisher's change, when they found that the word pinga, whence pinguín, was a slang term for "penis" in some countries, but later it was restored to Pinguín.

Memín was first featured in the 1940s in a comic book called "Pepín" and was later given his own magazine. The character originally was created by Alberto Cabrera in 1943, and later was drawn by Sixto Valencia Burgos. Valencia exaggerated the character by the instruction of Yolanda Vargas Dulché. Valencia also cites Ebony White as an influence. The original series had 372 chapters printed in sepia, and it has been republished in 1952 and 1961. In 1988 it was re-edited colorized, and in 2004 was re-edited again. Valencia worked on the reissues over the years, updating the drawings (clothes, settings and backgrounds) for the re-edits. It contains comedy and soap opera elements. However, since 2008 Valencia no longer works on the comic, having departed publishing house Editorial Vid.[1]

In addition to Mexico, Memín remains a popular magazine in the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Panama, Colombia, and other countries. At its peak, it had a weekly circulation of one and a half million issues in Mexico; as of mid-2005 it sells over 100,000 issues a week.[citation needed]

Contents

Characters

The stories were partially based on recollection of the childhood adventures of Yolanda Vargas Dulché in the Colonia Guerrero near downtown Mexico City. The character of Memín Pinguín was inspired by Cuban children seen by the author Yolanda Vargas Dulché on her travels. Memín is an alteration of Memo, the shortened form of Guillermo, her husband's name; Pinguín comes from pingo (roughly meaning mischievous, in an affectionate tone).

Memin is a restless child, not a very good student, not for lack of intelligence, but for not being able to pay attention (he is surprisingly good at arithmetic). He helps his mother working in the street, selling newspapers, and as a shoe shine boy. Memin reflects the life of a poor Mexican boy in Mexico City. Memín and his mother are the only Afro-Mexican characters.

Memín is accompanied in his adventures by a group of three loyal friends:

- Carlos "Carlangas" Arozamena: A street-wise curly-haired boy who was abandoned by his rich father and was raised by his working class mother. He likes to solve things with his fists, and rarely shows fear. He's a tough boy with a heart of gold. He is not as intelligent as Ernestillo but he manages to get the best scores in a private school test when he moved to live with his father.

- Ernesto "Ernestillo" Vargas: The intelligent and hard working one. His mother died when he was young and has since been raised by his father, an alcoholic carpenter. Ernestillo is so poor he has no shoes. Later, with the help of Ricardo and his friends, he has better clothes and helps his father to overcome his alcoholism and an accident that almost left him without a leg. He acts as the voice of reason of the group but sometimes he is not patient enough to send a "cozcorron" (noogie) to Memin. He is Memin's best friend and was involved in one of Memin's dreams when both go to China.

- Ricardo "Riquillo" Arcaraz: A blond rich boy who has traveled around the world. His father decided it would be better for him to attend a public school; a self-made man, he thinks his son was being pampered too much at private schools. At first he had significant troubles fitting in, until some incidents after school led to create a bond with Memin and his friends, to the point of standing up to his mother to defend them . He learns the value of work from Memín , as well as the realities and hardships of life. For a while, he even works as a shoeshine boy with Memín. When his parents tried to get a divorce, he ran away to Guadalajara to live with his godmother, but Memin, who accompanied him, left a note to Eufrosina, leading Ricardo's parents to them.

While Memín is undoubtedly the main character, his friends also have their own adventures. Other prominent characters are Memín's mother, Eufrosina, who makes a living by taking in washing, and Trifón, a fat boy whom they met at school some time after the story starts. Trifón subsequently died, and his death created an uproar among fans.

Although Memín is a comedy comic, it resembles soap operas in that the comic's story is a continuous one. Every week, the newest publication of Memín begins where the last publication had left off. In addition, because of the elements involved in the comic magazine's story, such as poverty, parental abandonment, death and alcoholism, often there are dramatic moments in the magazine as well.

Based on the popularity of Memín, Yolanda and her husband Don Guillermo de la Parra were able to found Editorial Vid, a comics publishing company that eventually published hundreds of titles of Mexican comics, some of them written by Yolanda and her husband. Some of these titles also had stories related to black people, such as "Rarotonga", "Majestad negra", and "Carne de Ebano", but only Memín was set in Mexico.

Racial issues

While Memín suffers a degree of racist taunting, especially in the first issues, the characters mocking him are depicted as either cruel or ignorant. As the story progresses, his race becomes less of an issue.

In one famous issue, Memín, having read that Cleopatra VII of Egypt took milk baths to lighten her skin, tries the same treatment. His mother weeps with sorrow that her son would want to change his skin color. A repentant Memín decides to be proud of his race and color to honor his good mother.

In another, Memín decides not to receive Communion at his church, after a cruel boy tells him blacks are not allowed in Heaven, pointing to the lack of black angels in religious paintings as proof (this was inspired by a popular song "Angelitos negros" that asked the same question and a popular Mexican motion picture of 1948 of the same name). Memín reasons that, since he is going to Hell anyway, he can get away with any mischief he wants. This prompted some Roman Catholic priests to boycott the magazine. After sales plummeted in response to the boycott, an issue was published in which Memín's friends, with the aid of the church priest, paint one of the angels in the church black; Memín returns to church and dreams of becoming an angel.

In yet another adventure called "Líos Gordos"[2] Memín and his friends travel to Texas to play soccer. They go for a chocolate milkshake, but the place refuses to sell to Memín, because it doesn't serve "Negroes". His friends stand up for him, get into a fight, and end up in jail.[3]

Memin in the popular culture

As a result of the character's fame, Memín has appeared in other magazines. In 1965, he gave a lengthy interview for the magazine Contenido, where he appeared in a tuxedo. In addition, he was considered one of the most famous members of the Mexican Scout Association, and included in the cover of their magazine in June 1995 to coincide with the publication of the "History of Mexican Comics" stamps by the Mexican Postal Service.

Controversy

Memín was criticized on its first runs (1960–1970), but the critics were more concerned with his popularity, since intellectuals of that time had a very low opinion of comics in general. The average age of the comic reader in Mexico was higher than in the United States, about 18 instead of 13,[4] so some argue the content of comics had a very strong influence on Mexican society. Memín was read mostly by poor and middle-class Mexicans. Some of the critics touch upon the racial aspects, but this topic was mostly ignored. Critics were more concerned with the stereotypical treatment of certain social themes and the values the stories typically reflect, which more or less echo the ideals of a Catholic middle class.[citation needed] Yolanda was very sensitive to critics, since they reflect heavily on sales. As Harold Hinds comments in his book Not just for children, the study of these comics is important to understand Mexican society.[4]

In June 2005, as part of a "History of Mexican Comics" series, the Mexican Postal Service (SEPOMEX) issued a series of postage stamps featuring the character of Memín. The stamps were deemed offensive by a number of African American community groups and politicians in the United States, including Jesse Jackson, prompting the Mexican government to assert that Memín had done a lot to oppose racism and that the stereotypical Warner Brothers' character Speedy Gonzales was never interpreted as offensive in Mexico.[5] LULAC and NCLR, Hispanic Americans civil rights organizations, also issued statements calling the stamps racist.

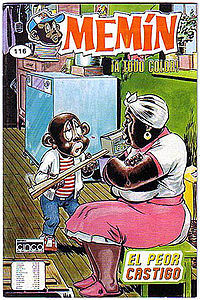

The charges of racism stem from the manner in which Pinguín and his mother are rendered, in the style of "darky iconography" (a form which, in the United States, has its roots in blackface and the American minstrel show tradition.) Early Mexican comic artists adopted this mode of depicting people of African descent which had become commonplace around the world. Memín and his mother are depicted stereotypically as the "pickaninny" and the "mammy", respectively. The dress and attitudes of Memín's mother are a caricature of Afro-Cuban women of the time[6] and mirror Afrodiasporic clothing in various Latin American countries.[7]

Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs Luis Ernesto Derbez declared to the press that "it is a total lack of knowledge of our culture; it looks to me that it is a total lack of respect to our culture that some people are making an issue out of this which does not resemble the reality."

According to Enrique Krauze, these different opinions may owe to the very different racial attitudes held by the British colonizers in the United States and the Spanish in Mexico, the much earlier, and nonviolent, abolition of slavery in Mexico (1810 through federal decree in Mexico versus 1865 through a civil war in the United States) and the nonexistence in Mexico of what in the United States were known as the "Jim Crow laws."[8]

The criticism from United States officials was not only ridiculed by public opinion leaders in Mexico and by most of the Mexican population, but it also spurred interest in the stamps: from the day they were criticized, they were offered in Internet auction sites for several times their face value, and Mexican collectors bought the full edition of 750,000 copies in a few days. Sales of the magazine increased, and the publisher decided to relaunch the series from the first issue alongside the current printing.[9] Mexican intellectuals both from right and left have denounced this criticism as an attack on Mexico, and political magazines like Proceso have questioned the chain of events that led to the criticism, making this criticism, a political issue against México.[citation needed]

In 2008, after complaints from an African-American shopper regarding what one news organization reported to be Memin's simian-like appearance and his "Aunt Jemima-like mother," all Memín periodicals were pulled from Wal-Mart stores in Texas.[10] This came after the latest issue titled "Memin para presidente" ("Memin for President") was being sold at locations with a large Hispanic population.[citation needed]

In 2011, in one of the mexican reprints of the comic, there is a picture involving Memin Pinguin walking alongside Michelle Obama. Memin says "and this one is really a work that also the afroamerican really want to do" poking fun on the 2005 comment of President Fox, but probably also telling the irony over the fact that an afroamerican is currently the president of the United States (and that the lastest issue of Memin Pinguin in USA was called Memin for President).

See also

References

- ^ http://comicmexicano.blogspot.com/2008/04/memn-pingun-cambia-de-dibujante.html

- ^ http://www.supermexicanos.com/memin/memin.5.jpg

- ^ Lios Gordos 2 on Flickr - Photo Sharing!

- ^ a b Not Just for Children: The Mexican Comic Book in the Late 1960s and 1970s by Harold E. Hinds, Jr. and Charles M. Tatum

- ^ Tacha Casa Blanca de racista estampilla de Memín", El Universal, June 30, 2005

- ^ Interview with Sixto Valencia (in spanish),[1] "Interview with Sixto Valencia (in spanish)"],lanuez.blogspot.com, July 12, 2008

- ^ Memin: Racist Cartoon?

- ^ Enrique Krauze, "The Pride In Memin Pinguin", Washington Post, July 12, 2005

- ^ "Mexican comic book 'Memin Pinguin' sold at Wal-Mart called racist". Dallas Morning News. 2008-07-08. http://www.dallasnews.com/sharedcontent/dws/dn/yahoolatestnews/stories/070908dntexwalmart.35a796ac.html?npc.

- ^ Ed Lavandera, "Mexican comic-book character called racist", CNN, July 9, 2008

External links

Categories:- 1940s comics

- Mexican comics titles

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.