- Egyptian Vulture

-

Egyptian Vulture

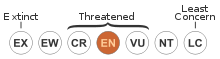

Adult N. p. ginginianus Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Accipitriformes Family: Accipitridae Genus: Neophron

Savigny, 1809Species: N. percnopterus Binomial name Neophron percnopterus

(Linnaeus, 1758)

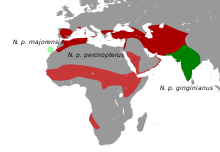

Distribution of the populations, birds breeding in Europe winter in Africa The Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus) is a small Old World vulture, found widely distributed from southwestern Europe and northern Africa to southern Asia. It is the only living member of the genus Neophron. It has sometimes also been known as the White Scavenger Vulture or Pharaoh's Chicken. Like other vultures it soars on thermals and the underwing black and white pattern and wedge tail make it distinctive. It sometimes uses stones to break the eggs of birds making it one of the few birds that make use of tools. Birds that breed in the temperate region migrate south in winter while tropical populations are relatively sedentary. Populations of this species have declined in the 20th Century and some isolated island forms are particularly endangered.

Contents

Taxonomy and systematics

The genus Neophron contains only a single species. A few prehistoric species from the Neogene of North America placed in the genus Neophrontops (the name meaning "looks like Neophron") are believed to have been very similar to these vultures in lifestyle but the relationships are unclear.[2][3] The genus is considered to be among the oldest branching species within the vultures and the closest living relative is the Lammergeier (Gypaetus barbatus).[4][5] Some authors have suggested that they should be placed in a separate subfamily, the Gypaetinae.[6] There are three widely recognised subspecies of the Egyptian Vulture although there is considerable gradation due to movement and intermixing of the populations.[7] A subspecies rubripersonatus from Baluchistan and the northwestern Himalayas (said to have a dark bill with a yellowish tip) described by Nikolai Zarudny and Härms is rarely recognized.[8][9][10]

- N. p. percnopterus, the nominate subspecies, has the largest range, occurring in southern Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and the north-west of the Indian subcontinent. Populations breeding in the temperate zone migrate south during winter.

- N. p. ginginianus, the smallest subspecies with an all pale bill, occurs in most of the Indian subcontinent. The name is derived from Gingee in southern India.[11]

- N. p. majorensis, the Canarian Egyptian Vulture, the largest subspecies with by far the smallest and most restricted population, is found only in the eastern Canary Islands where they are known by the name of guirre. Described as a new subspecies only in 2002, studies suggest that it is more genetically distant from N. p. percnopterus than N. p. ginginianus is. Unlike neighbouring populations in Africa and southern Europe, they are not migratory and are consistently larger in size. The name majorensis is derived from “Majorata”, the ancient name for the island of Fuerteventura. The island was named by Spanish conquerors in the 15th century after the “Majos”, the main native Guanche tribe there.[7][12] A study suggests that the species colonized the island around 2500 years ago and the establishment of the population may have been aided by human colonization at around the same time.[13]

The genus name is derived from Greek mythology. Neophron was the son of Timandra, the mistress of Aegypius. Neophron tricked Aegypius into sleeping with his own mother Bulis imagining it was Timandra. When the deception was found, Bulis sought to take out the eyes of her son but Zeus changed Aegypius and Neophron into vultures.[14] The species name refers to the black wings ("περκνóς" =blue-black +"πτερόν"=wing).[15]

Description

The adult plumage is white, with black flight feathers in the wings. The white plumage however usually appears soiled due to the habits of the birds. The bill is slender and long and the tip of the upper mandible is hooked. The nostril is an elongated horizontal slit. The feathers on the neck are long and form a hackle. The wings are pointed with the third primary being the longest. The tail is wedge shaped. The claws are long and straight and the 3rd and 4th toes are slightly webbed at the base. The bill is black in the nominate population but is pale or yellowish in the smaller Indian ginginianus, but this variation may need further study.[9] The facial skin is yellow and crop is unfeathered.[16] Young birds are blackish or chocolate brown with black and white patches.[16]

The adult Egyptian Vulture measures 47–70 cm (21–28 in) from the point of the beak to the extremity of the tail feathers and 1.5-1.7 metre (5-5.6 ft) between the tips of the wings. In N. p. ginginianus males are about 47.5-52.5 cm long while females are 52-55.5 cm long.[9] It weighs about 2 kilograms (4.4 lbs) although birds of the subspecies majorensis average 2.4 kilograms (5.3 lbs), about 18% heavier than birds from Iberia.[17]

Distribution

Egyptian Vultures are widely distributed and may be found in southern Europe, in northern Africa, and in western and South Asia. Their habitat is mainly in the dry plains and nest mainly in arid and rocky hill regions. It is a rare vagrant in Sri Lanka.[16] Vagrants are sometimes found further north in Europe and in South Africa.[18] European populations have been recorded migrating south into Africa about 3500 to 5500 km, sometimes covering nearly 500 km in a single day. A bird that bred in France migrated south only in its third year.[19][20] Like many other soaring diurnal migrants, they avoid making long crossings over water.[21] Italian birds cross over through Sicily and into Tunisia over the islands of Marettimo and Pantelleria.[22]

Behaviour and ecology

This species is often seen soaring in thermals often with other scavengers. They feed on a range of food including mammal faeces (especially human[23]), insects in dung, carrion as well as vegetable matter and sometimes small live prey.[24] Studies suggest that feeding on mammalian (in this case, ungulate) faeces helps in obtaining carotenoid pigments responsible for the bright yellow and orange facial skin.[25] They are usually silent but near the nest they make high-pitched mewing or hissing notes.[9]

They roost communally[26] and nests are often traditionally used year after year. Birds are however usually seen singly or in pairs. They are socially monogamous and pair bonds may be maintained for more than one breeding season. Extra-pair copulation with neighbouring birds is however noted and adult males tend to stay close to the female before and during the egg laying period.[27] The nest sites include cliffs, buildings as well as trees.[9] Unusual nest sites such as on the ground have been recorded in N. p. ginginianus and N. p. majorensis.[28][29][30] The nesting season is February to April in India. Both parents incubate and the two eggs hatch after about 42 days.[16] The second chick may hatch after an interval of 3 to 5 days or more. The longer the interval, the more likely is the death of the second chick due to starvation.[31] In areas where nests are close to each other, young birds may sometimes move to neighbouring nests to obtain food.[32] In the Spanish population, young fledge and leave the nest after 90 to 110 days.[33] Young birds disperse from their nest site and birds in Spain have been recorded to move nearly 500 km away from their nest site.[34][35] The full adult plumage is attained in the fourth or fifth year. In captivity, birds have been known to live for up to 37 years.[36]

Healthy adults do not have any predators but mortality from powerlines, pollution and poisoning have been noted. Young birds have been known to be taken by Golden Eagles, Eagle Owls and Red Fox. Birds falling off the cliffs may be picked up by Jackals.[37]

The nominate population, especially in Africa is well known for their use of stones as tools. When a large egg, such as that of an ostrich or bustard is located, the bird approaches it with a large pebble held in the bill and tosses it by standing near the egg and swinging the neck down. The operation is repeated until the egg cracks from the blows.[38] This behaviour has not been recorded in N. p. ginginianus.[9] Tests with hand-reared and wild birds suggest that the behaviour is shown by naive birds raised alone in captivity (and therefore not learnt from observing other birds) and is displayed once they associate eggs with food. They show a strong preference for rounded pebbles rather than jagged rocks.[39] Bulgarian birds have been observed to use twigs to roll up and gather strands of wool that they make use of in their nest lining.[40]

Conservation status

The Egyptian Vulture is declining in large parts of its range, often severely. In Europe and most of the Middle East, it is half as plentiful as it was about twenty years ago, and the populations in India and southwestern Africa have greatly declined. In 1967-70, the area around Delhi was estimated to have 12000-15000 of these vultures with an average density of about 5 pairs per 10 km2.[41][42] The cause of the decline is not known but has been linked with the use of the NSAID Diclofenac which has been known to cause death in Gyps vultures.[43] In southern Europe, suggested causes of the decline include poisoning by accumulation of lead, pesticides (especially due to large-scale use in the control of Schistocerca gregaria locust swarms) and by electrocution.[17][44] Studies in Spain have suggested that the absorption of veterinary antibiotics suppresses their innate immunity, making them more prone to infection.[45]

The population in the Canary Islands have been isolated from populations in Europe and Africa for a significant period of time and have declined greatly and are of particular concern due to their genetic distinctiveness. The Canarian Egyptian Vulture was historically common, occurring on the islands of La Gomera, Tenerife, Gran Canaria, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote. It is now restricted to Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, the two easternmost islands. The total population in 2000 was estimated at about 130 individuals, including 25–30 breeding pairs.[17][46] The island birds appear to be more susceptible to infections.[47] Island birds appear to accumulate significant amounts of lead from scavenging on hunted animal carcasses and the long-term effect of this poison at a sublethal level is not known although it alters the mineralization of their bones.[48] In order to provide safe and uncontaminated food for nesting birds, attempts have been made to create "vulture restaurants" where carcasses are made available. These interventions however may also encourage opportunist predators and scavengers to concentrate at the site and pose a threat to nesting birds in the vicinity.[49]

In culture

Egyptian Vulture

in hieroglyphsIn Ancient Egypt, the vulture hieroglyph was the uniliteral sign used for the glottal sound (3). The Hebrew word rachamah/racham used in the Bible and translated into English as gier-eagle refers to this species.[15][50] The bird was held sacred to Isis. The association of the vulture as a symbol of royalty in Egyptian culture led to the use of the name "Pharaoh's Chicken" for the species.[51][52]

A southern Indian temple at Thirukalukundram near Chengalpattu is famed for a pair of birds that have reputedly visited the site for "centuries". These birds are traditionally fed by the temple priests and arrive before noon to feed on offerings made from rice, wheat, ghee and sugar. Although punctual, the failure of the birds to turn up was attributed to the presence of "sinners" among the onlookers.[16][53][54] Legend has it the vultures (or "eagles") represent eight sages who were punished by Shiva with two of them leaving in each of a series of epochs.[55][56]

The habit of coprophagy has led to the Spanish names of "churretero" and "moñiguero" which mean "dung-eater".[25] British naturalists in colonial India considered them among the ugliest birds and their habit of feeding on faeces was particularly despised.[57]

Footnotes

- ^ IUCN redlist.

- ^ Feduccia 1974.

- ^ Hertel 1995.

- ^ Wink 1995.

- ^ Wink, Heidrich & Fentzloff 1996.

- ^ Seibold & Helbig 1995.

- ^ a b Donázar et al. 2002b.

- ^ Zarudny & Härms 1902.

- ^ a b c d e f Rasmussen & Anderton 2005.

- ^ Hartert 1910.

- ^ Pittie 2004.

- ^ Kretzmann et al. 2003.

- ^ Agudo et al. 2010.

- ^ Grimal 1996.

- ^ a b Koenig 1907.

- ^ a b c d e Ali & Ripley 1978.

- ^ a b c Donázar et al. 2002a.

- ^ Mundy 1978.

- ^ Meyburg et al. 2004.

- ^ García-Ripollés, López-López & Urios 2010.

- ^ Yosef & Alon 1997.

- ^ Agostini et al. 2004.

- ^ Whistler 1949.

- ^ Prakash & Nanjappa 1988.

- ^ a b Negro et al. 2002.

- ^ Donázar, Ceballos & Tella 1996.

- ^ Donázar, Ceballos & Tella 1994.

- ^ Biddulph 1937.

- ^ Paynter 1924.

- ^ Gangoso 2005.

- ^ Donázar & Ceballos 1989a.

- ^ Donázar & Ceballos 1990.

- ^ Donázar & Ceballos 1989b.

- ^ Elorriaga et al. 2009.

- ^ Ceballos & Donázar 1990.

- ^ Grande et al. 2009.

- ^ Stoyanova & Stefanov 1993.

- ^ van Lawick-Goodall & van Lawick-Goodall 1966.

- ^ Thouless, Fanshawe & Bertram 1989.

- ^ Stoyanova, Stefanov & Schmutz 2010.

- ^ Galushin 2001.

- ^ Galushin 1975.

- ^ Cuthbert et al. 2006.

- ^ Hernández & Margalida 2009.

- ^ Lemus & Blanco 2009.

- ^ Palacios 2004.

- ^ Gangoso et al. 2009b.

- ^ Gangoso et al. 2009a.

- ^ Cortés-Avizanda et al. 2009.

- ^ Coultas & Harland 1876, p. 138.

- ^ Ingerson 1923, p. 34.

- ^ Thompson 1895, p. 48.

- ^ Neelakantan 1977.

- ^ Siromoney 1977.

- ^ Pope 1900, p. 260.

- ^ Thurston 1906, p. 252.

- ^ Dewar 1906.

- Cited works

- Agudo, Rosa; Rico, Ciro; Vilà, Carles; Hiraldo, Fernando; Donázar, José (2010). "The role of humans in the diversification of a threatened island raptor". BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 384. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-384. PMC 3009672. PMID 21144015. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3009672.

- Ali, Sálim; Ripley, Sidney Dillon (1978). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan, Volume 1 (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 310–314. ISBN 978-0-195-62063-4.

- Biddulph, C. H. (1937). "Unusual site for the nest of the White Scavenger Vulture Neophron percnopterus ginginianus (Lath.)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 39 (3): 635–636.

- BirdLife International (2009). "Neophron percnopterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. International Union for Conservation of Nature. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/144347. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- Ceballos, Olga; Donázar, José Antonio (1990). "Roost-tree characteristics, food habits and seasonal abundance of roosting Egyptian Vultures in northern Spain" (pdf). Journal of Raptor Research 24 (1–2): 19–25. ISSN 0892-1016. http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/jrr/v024n01-02/p00019-p00025.pdf.

- Cocchi, Leonardo; Bassi, Enrico; Logozzo, Daniela; Panuccio, Michele; Mellone, Ugo; Premuda, Guido; Agostini, Nicolantonio (2004). "Crossing the sea en route to Africa: autumn migration of some Accipitriformes over two Central Mediterranean islands". Ring 26 (2): 71–78. doi:10.2478/v10050-008-0062-6. http://www.raptormigration.org/Agostini%20et%20al%202004%20-%20Ring.pdf.

- Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Carrete, M.; Serrano, D.; Donázar, J. A. (2009). "Carcasses increase the probability of predation of ground-nesting birds: a caveat regarding the conservation value of vulture restaurants". Animal Conservation 12: 85–88. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2008.00231.x. http://www.ebd.csic.es/carnivoros/personal/carrete/martina/recursos/34.%20Cortes-avizanda%20et%20al%20(2009)%20Anim%20Cons.pdf.

- Coultas, Harland (1876). Zoology of the Bible. London: Wesleyan Conference Office. http://www.archive.org/stream/zoologybible00coulgoog#page/n154/mode/1up/.

- Cuthbert, R.; Green, R. E.; Ranade, S.; Saravanan, S.; Pain, D. J.; Prakash, V.; Cunningham, A. A. (2006). "Rapid population declines of Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) and red-headed vulture (Sarcogyps calvus) in India". Animal Conservation 9 (3): 349–354. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00041.x.

- Dewar, Douglas (1906). Bombay Ducks. John Lane, London. pp. 277. http://www.archive.org/stream/bombayducksaccou00dewa#page/277/mode/1up/.

- Donázar, José Antonio; Ceballos, Olga (1989). "Growth rates of nestling Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus in relation to brood size, hatching order and environmental factors" (pdf). Ardea 77 (2): 217–226. ISSN 0373-2266. http://www.ebd.csic.es/carnivoros/personal/donazar/joseadonazar/s_p_pdfs/23_Growth%20rates%20of%20nestling%20Egyptian%20vultures%20Neophron%20percnopterus%20in%20relation%20to%20brood%20size_hatching.pdf.

- Donázar, José Antonio; Ceballos, Olga (1989). "Post-fledging dependence period and development of flight and foraging behaviour in the Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus" (pdf). Ardea 78 (3): 387–394. ISSN 0373-2266. http://www.ebd.csic.es/carnivoros/personal/donazar/joseadonazar/s_p_pdfs/31_Post-fledging%20dependece%20period%20and%20development%20of%20flight%20and%20foraging%20behaviour%20in%20the%20Egyptian%20vult.pdf.

- Donazar, JOSÉ A.; Ceballos, Olga (2008). "Acquisition of food by fledgling Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus by nest-switching and acceptance by foster adults". Ibis 132 (4): 603–607. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1990.tb00284.x. http://www.ebd.csic.es/carnivoros/personal/donazar/joseadonazar/s_p_pdfs/29_Acquisition%20of%20food%20by%20fledging%20Egyptian%20vultures%20Neophron%20percnopterus%20by%20nest-switching%20and%20accept.pdf.

- Donazar, J. A.; Ceballos, O.; Tella, J. L. (1994). "Copulation behaviour in the Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus". Bird Study 41: 37–41. doi:10.1080/00063659409477195. http://www.ebd.csic.es/carnivoros/personal/donazar/joseadonazar/s_p_pdfs/49_Copulation%20behaviour%20in%20the%20Egyptian%20vulture%20Neophron%20percnopterus.pdf.

- Donázar, José A.; Ceballos, Olga; Tella, José L. (1996). "Communal roosts of Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus): dynamics and implications for the species conservation". In Muntaner, J.; J. (pdf). Biology and Conservation of Mediterranean Raptors. Monografía SEO-BirdLife, Madrid. pp. 189–201. http://www.ebd.csic.es/carnivoros/personal/donazar/joseadonazar/s_p_pdfs/60_Communal%20roosts%20of%20egyptian%20vultures.pdf.

- Donázar, J (2002). "Conservation status and limiting factors in the endangered population of Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) in the Canary Islands". Biological Conservation 107: 89–97. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00049-6. http://www.cesarjpalacios.com/Biologicalconservation.pdf.

- Donázar, José Antonio; Negro, Juan José; Palacios, César Javier; Gangoso, Laura; Godoy, José Antonio; Ceballos, Olga; Hiraldo, Fernando; Capote, Nieves (2002). "Description of a new subspecies of the Egyptian Vulture (Accipitridae: Neophron percnopterus) from the Canary Islands" (pdf). Journal of Raptor Research 36 (1): 17–23. ISSN 0892-1016. http://www.cesarjpalacios.com/Subespecie%20JRR.pdf.

- Elorriaga, Javier; Zuberogoitia, Iñigo; Castillo, Iñaki; Azkona, Ainara; Hidalgo, Sonia; Astorkia, Lander; Ruiz-Moneo, Fernando; Iraeta, Agurtzane (2009). "First Documented Case of Long-Distance Dispersal in the Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus)". Journal of Raptor Research 43 (2): 142–145. doi:10.3356/JRR-08-53.1. http://www.icarus.es/product_document/url/79/First_documented_case.pdf.

- Feduccia, Alan (1974). "Another Old World Vulture from the New World" (pdf). The Wilson Bulletin 86 (3): 251–255. http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Wilson/v086n03/p0251-p0255.pdf.

- Galushin, V. M. (1975). "A comparative analysis of the density of predatory birds in two selected areas within the Palaearctic and Oriental regions, near Moscow and Delhi (IOC Abstracts)". Emu 74: 331.

- Galushin, V. M. (2001). "Populations of vultures and other raptors in Delhi and neighboring areas from 1970's to 1990's". In Parry-Jones J & T Katzner (pdf). Report from the Workshop on Indian Gyps vultures: 4th Eurasian congress on raptors. Sevilla, Spain: aviary.org. pp. 13–15. http://www.aviary.org/cons/pdf/Vulture%20Workshop%20Reports_Seville%202001.pdf.

- Gangoso, Laura (2005). "Ground nesting by Egyptian Vultures (Neophron percnopterus) in the Canary Islands" (pdf). Journal of Raptor Research 39 (2): 186–187. ISSN 0892-1016. http://www.alimochefuerteventura.com/documentos/Ground-nesting-by%20Egyptian-Vultures.pdf.

- Gangoso, Laura; Grande, Juan M.; Lemus, Jesús A.; Blanco, Guillermo; Grande, Javier; Donázar, José A. (2009). Getz, Wayne M.. ed. "Susceptibility to Infection and Immune Response in Insular and Continental Populations of Egyptian Vulture: Implications for Conservation". PLoS ONE 4 (7): e6333. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006333. PMC 2709727. PMID 19623256. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2709727.

- García-Ripollés, Clara; López-López, Pascual; Urios, Vicente (2010). "First description of migration and wintering of adult Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus tracked by GPS satellite telemetry". Bird Study 57 (2): 261–265. doi:10.1080/00063650903505762. http://rapaces.lpo.fr/sites/default/files/vautour-percnoptere/490/garcia-ripollesbird-study-2010.pdf.}

- Grande, Juan M.; Serrano, David; Tavecchia, Giacomo; Carrete, Martina; Ceballos, Olga; Díaz-Delgado, Ricardo; Tella, José L.; Donázar, José A. (2009). "Survival in a long-lived territorial migrant: effects of life-history traits and ecological conditions in wintering and breeding areas". Oikos 118 (4): 580–590. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17218.x. http://www.imedea.uib.es/bc/gep/docs/pdfsgrupo/articulos/2009/2009grande%20y%20tavecchia.pdf.

- Grimal, Pierre (1996). The dictionary of classical mythology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 18. ISBN 0631201025.

- Hartert, Ernst (1910). Die Vögel der paläarktischen Fauna. Volume 2. Friendlander & Sohn, Berlin. pp. 1200–1202. http://www.archive.org/stream/dievgelderpal02hart#page/1200/mode/1up.

- Hernández, Mauro; Margalida, Antoni (2009). "Poison-related mortality effects in the endangered Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) population in Spain". European Journal of Wildlife Research 55 (4): 415–423. doi:10.1007/s10344-009-0255-6. http://www.gypaetus.com/fotos/noticias/Hern_ndez___Margalida_2009.pdf.

- Hertel, Fritz (1995). "Ecomorphological indicators of feeding behavior in recent and fossil raptors" (pdf). The Auk 112 (4): 890–903. http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Auk/v112n04/p0890-p0903.pdf.

- Ingerson, Ernest (1923). Birds in legend, fable and folklore. New York: Longmans, Green and Co. http://www.archive.org/stream/birdsinlegendfab00inge#page/34/mode/1up/.

- Koenig, Alexander (1907). "Die Geier Aegyptens". Journal für Ornithologie 55: 59–134. doi:10.1007/BF02098853.

- Kretzmann, Maria B.; Capote, N.; Gautschi, B.; Godoy, J.A.; Donázar, J.A.; Negro, J.J. (2003). "Genetically distinct island populations of the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus)". Conservation Genetics 4 (6): 697–706. doi:10.1023/B:COGE.0000006123.67128.86.

- Lemus, J. A.; Blanco, G. (2009). "Cellular and humoral immunodepression in vultures feeding upon medicated livestock carrion". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 276 (1665): 2307–2313. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0071. PMC 2677603. PMID 19324751. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2677603.

- Meyburg, Bernd-U.; Gallardo, Max; Meyburg, Christiane; Dimitrova, Elena (2004). "Migrations and sojourn in Africa of Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus) tracked by satellite". Journal of Ornithology 145 (4): 273–280. doi:10.1007/s10336-004-0037-6.

- Mundy, P (1978). "The Egyptian vulture (Neophron Percnopterus) in Southern Africa". Biological Conservation 14 (4): 307–315. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(78)90047-2.

- Neelakantan, K. K. (1977). "The sacred birds of Thirukkalukundram". Newsletter for Birdwatchers 17 (4): 6.

- Negro, J. J.; Grande, J. M.; Tella, J. L.; Garrido, J.; Hornero, D.; Donázar, J. A.; Sanchez-Zapata, J. A.; Benítez, J. R. et al. (2002). "An unusual source of essential carotenoids" (pdf). Nature 47 (6883): 807. doi:10.1038/416807a. http://web.uam.es/personal_pdi/ciencias/jonate/Ecologia/Tema%2018/Negro_etal,%202002.pdf.

- Palacios, CÉSAR-Javier (2004). "Current status and distribution of birds of prey in the Canary Islands". Bird Conservation International 14 (03). doi:10.1017/S0959270904000255. http://www.cesarjpalacios.com/Birdsofpreyincanaryislands.pdf.

- Paynter, W. P. (1924). "Lesser White Scavenger Vulture N. ginginianus nesting on the ground". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 30 (1): 224–225.

- Pittie, Aasheesh (2004). "A dictionary of scientific bird names originating from the Indian region" (pdf). Buceros 9 (2). http://www.bnhsenvis.nic.in/pdf/Vol%209%20(2)dictionary.pdf.

- Pope, G. U. (1900). The Tiruvacagam or Sacred utterances of the Tamil poet, saint, and sage Manikka-vacagar. Clarendon Press, Oxford. http://www.archive.org/stream/tiruvaagamorsa00manirich#page/259/mode/1up.

- Prakash, Vibhu; Nanjappa, C. (1988). "An instance of active predation by Scavenger Vulture (Neophron p. ginginianus) on Checkered Keelback watersnake (Xenochrophis piscator) in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 85 (2): 419.

- Rasmussen, P. C.; Anderton, J. C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. p. 89.

- Seibold, I.; Helbig, A. J. (1995). "Evolutionary History of New and Old World Vultures Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of the Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 350 (1332): 163–178. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0150. PMID 8577858.

- Siromoney, Gift (1977). "The Neophron Vultures of Thirukkalukundram". Newsletter for Birdwatchers 17 (6): 1–4. http://www.archive.org/stream/IndologicalEssays2/IndologySiromoney1#page/n107/mode/1up/.

- Stoyanova, Yva; Stefanov, Nikolai (1993). "Predation upon nestling Egyptian Vultures (Neophron percnopterus) in the Vratsa Mountains of Bulgaria" (pdf). Journal of Raptor Research 27 (2): 123. ISSN 0892-1016. http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/jrr/v027n02/p00123-p00123.pdf.

- Stoyanova, Yva; Stefanov, Nikolai; Schmutz, Josef K. (2010). "Twig Used as a Tool by the Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus)". Journal of Raptor Research 44 (2): 154–156. doi:10.3356/JRR-09-20.1.

- Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth (1895). A glossary of Greek birds. Oxford: Clarendon Press. http://www.archive.org/stream/glossaryofgreekb00thomuoft#page/47/mode/1up.

- Thouless, C. R.; Fanshawe, J. H.; Bertram, B. C. R. (2008). "Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus and Ostrich Struthio camelus eggs: the origins of stone-throwing behaviour". Ibis 131: 9–15. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1989.tb02737.x.

- Thurston, E. W. (1906). Etnographic notes in southern India. Government Press, Madras. http://www.archive.org/stream/ethnographicnot00edgagoog#page/n334/mode/1up/.

- Van Lawick-Goodall, Jane; Van Lawick-Goodall, Hugo (1966). "Use of Tools by the Egyptian Vulture, Neophron percnopterus". Nature 212 (5069): 1468–1469. doi:10.1038/2121468a0.

- Whistler, Hugh (1949). Popular Handbook of Indian Birds (4 ed.). London: Gurney & Jackson. pp. 356–357. ISBN 1406745766. http://www.archive.org/stream/popularhandbooko033226mbp#page/n406/mode/1up.

- Wink, Michael (1995). "Phylogeny of Old and New World Vultures (Aves: Accipitridae and Cathartidae) Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of the Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene" (pdf). Zeitschrift for Naturforschung C 50 (11/12): 868–882. http://www.uni-heidelberg.de/institute/fak14/ipmb/phazb/pdf-files/1995%20Pdf.Pubwink/24.%201995.pdf.

- Wink, Michael; Heidrich, Petra; Fentzloff, Claus (1996). "A mtDNA phylogeny of sea eagles (genus Haliaeetus) based on nucleotide sequences of the cytochrome b-gene". Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 24 (7–8): 783–791. doi:10.1016/S0305-1978(96)00049-X. http://www.uni-heidelberg.de/institute/fak14/ipmb/phazb/pubwink/1996/20_1996.pdf.

- Yosef, Reuven; Alon, Dan (1997). "Do immature Palearctic Egyptian Vultures Neophron percnopterus remain in Africa during the northern summer?" (pdf). Vogelwelt 118: 285–289. http://www.birdsofeilat.com/pdfiles/1997%20Egyptian%20Vulture%20migration.pdf.

- Zarudny, V.; Härms, M. (1902). "Neue Vogelarten" (in German). Ornithologische Monatsberichte (4): 49–55. http://www.archive.org/stream/ornithologisch101902berl#page/52/mode/1up.

External links

- BTO BirdFacts - Egyptian Vulture

- A photo story on how the Egyptian Vulture can crack an Ostrich egg

- Ageing and sexing (PDF) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta

Old World vultures (subfamily: Aegypiinae) Genus Aegypius Gypaetus Gypohierax Gyps Griffon Vulture • White-rumped Vulture • Rüppell's Vulture • Indian Vulture • Slender-billed Vulture • Himalayan Griffon Vulture • White-backed Vulture • Cape VultureNecrosyrtes Neophron Egyptian VultureSarcogyps Torgos Trigonoceps Categories:- IUCN Red List endangered species

- Old World vultures

- Genera of birds

- Tool-using species

- Birds of Europe

- Birds of Asia

- Birds of Africa

- Coprophagous animals

- Animals described in 1758

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.