- Matilda of Tuscany

-

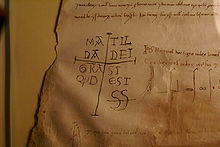

Matilda of Tuscany (Italian: Matilde, Latin: Matilda, Mathilda) (1046 – 24 July 1115) was an Italian noblewoman, the principal Italian supporter of Pope Gregory VII during the Investiture Controversy. She is one of the few medieval women to be remembered for her military accomplishments. She is sometimes called la Gran Contessa ("the Great Countess") or Matilda of Canossa after her ancestral castle of Canossa.

Contents

Childhood and regency

She was the daughter of Boniface III, ruler of many counties, among them Reggio, Modena, Mantua, Brescia, and Ferrara. He held a great estate on both sides of the Apennines, though the greater part was in Lombardy and Emilia. Matilda's mother was Beatrice, a daughter of Frederick II, Duke of Upper Lorraine, and of Matilda, daughter of Herman II of Swabia.

Matilda's place of birth is unknown. Mantua, Modena, Cremona, and Verona have all been suggested, though scholarly opinion favours Lucca or the nearby castle of Porcari.[1] Based on her fluency in German, some authors have asserted that she was born in Lorraine, her mother's province. She was her parents' youngest child, but her father was murdered in 1052 and one year later (1053) her older sister Beatrice (namesake of their mother) also died. The elder Beatrice, in order to protect her children's inheritance, married Godfrey the Bearded, a cousin who had been Duke of Upper Lorraine before rebelling against the Emperor Henry III. The two were married in 1053 or 1054 in the church of San Pietro at Mantua by Pope Leo IX himself as he returned from a trip to Germany. At the same time, Matilda was betrothed to Godfrey the Hunchback, a son of Godfrey the Bearded by a previous marriage and thus her stepbrother.

Henry III was enraged by Beatrice's unauthorised marriage to his enemy and he descended into Italy in the early spring of 1055, arriving at Verona in April and then Mantua by Easter. Beatrice wrote to him seeking a safe-conduct to explain herself; this granted, she travelled with her young son Frederick, now Margrave of Tuscany, and her mother, Matilda of Swabia, a sister of the emperor's grandmother Gisela. The younger Matilda was left in either Lucca or Canossa and she may have passed the next few years between those two places in the custody of her stepfather. Initially, Henry refused to see Beatrice, but eventually he had her imprisoned in rough conditions; the young Frederick was treated more appropriately, but he died in Henry's custody nonetheless (the rumours that he was murdered are baseless).[2] The death of her brother made the eight-year-old Matilda the sole heiress of the vast lands of her father, under her stepfather's guardianship.

With his wife now imprisoned, Godfrey returned to Germany to stir up rebellion and draw Henry out of Italy, but the emperor merely took Beatrice and Frederick with him. Some later historian aver that Beatrice went willingly to see her former homeland. Whatever the case, Godfrey and his ally, Baldwin V of Flanders, had forced the emperor to come to terms of peace by mid-1056 and Godfrey was permitted to return to Italy to administer his stepdaughter's estates. Henry soon died and the council which was held under the direction of Pope Victor II at Cologne formally restored Godfrey to imperial favour. He and Beatrice were back in Italy by late that year.

Matilda's family became heavily involved in the series of disputed papal elections of the last half of the eleventh century. Her stepfather's brother Frederick became Pope Stephen IX, while both of the following two popes, Nicholas II and Alexander II had been Tuscan bishops. Matilda made her first journey to Rome with her family in the entourage of Nicholas in 1059. Her parents' forces were used to protect these popes and fight against antipopes. Some stories claim the adolescent Matilda took the field in some of these engagements, but no evidence supports this.

Under the tutelage of Arduino della Padule, however, she did learn the military arts, such as horseriding and arms. According to Lodovico Vedriani, there were two suits of her armour in the "Quattro Castelli" until 1622, when they were sold in the market of Reggio. The "Qattro Castelli" were four castles — Montezane, Montelucio, Montevetro, and Bianell (Bibianello) — perched by Matilda atop hills to guard the route up to Canossa. Matilda could speak "the Teuton tongue" (German) and "the beautiful language of the Franks" (French) according to her biographer, Domnizo. She could also write in Latin.

Sometime in this period, Matilda finally married her stepbrother Godfrey the Hunchback, for whom she had great disdain. She gave birth in 1071 to a daughter, Beatrice. Virtually all current biographies of Matilda assert that the child died in its first year of infancy, however genealogies contemporaneous with Michelangelo Buonarroti claimed that Beatrice survived, and Michelangelo himself falsely claimed to be a descendant of Beatrice and, therefore, Matilda. Michelangelo's claim was supported at the time by the reigning Count of Canossa. The Catholic Church, possibly motivated by its claim against her property, has always asserted that Matilda never had any child at all. Matilda and Godfrey became estranged after Godfrey the Bearded's death in 1069, and he returned to Germany, where he eventually received the duchy of Lower Lorraine.

Conflict between Henry IV and the Papacy

Both Matilda's mother and husband died in 1076, leaving her in sole control of her great Italian patrimony as well as lands in Lorraine, while at the same time matters in the conflict between Pope Gregory VII and the German king Henry IV were at a crisis point. The Pope had excommunicated the King, causing a weakening of Henry's German support. Henry crossed the Alps that winter, appearing early in 1077 as a barefoot penitent in the snow before the gates of Matilda's ancestral castle of Canossa, where the pope was staying.

This famous meeting did not settle matters for long. In 1080 Henry was excommunicated again, and the next year he crossed the Alps, aiming either to get the pope to end the excommunication and crown him emperor, or to depose the pope in favor of someone more co-operative.

Matilda controlled all the western passages over the Apennines, forcing Henry to approach Rome via Ravenna. Even with this route open, he would have difficulties besieging Rome with a hostile territory at his back. Some of his allies defeated Matilda at the battle of Volta Mantovana (near Mantua) in October 1080, and by December the citizens of Lucca, then the capital of Tuscany, had revolted and driven out her ally Bishop Anselm. She is believed to have commissioned the renowned Ponte della Maddalena where the Via Francigena crosses the river Serchio at Borgo a Mozzano just north of Lucca.

In 1081, Matilda suffered some further losses, and Henry formally deposed her in July. This was not enough to eliminate her as a source of trouble, for she retained substantial allodial holdings. She remained as Pope Gregory's chief intermediary for communication with northern Europe even as he lost control of Rome and was holed up in the Castel Sant'Angelo. After Henry had obtained the Pope's seal, Matilda wrote to supporters in Germany only to trust papal messages that came though her.

Henry's control of Rome enabled him to have his choice of pope, Antipope Clement III, consecrated and in turn for this pope to crown Henry as emperor. That done, Henry returned to Germany, leaving it to his allies to attempt Matilda's dispossession. These attempts foundered after Matilda routed them at Sorbara (near Modena) on July 2, 1084.

Gregory VII died in 1085, and Matilda's forces, with those of Prince Jordan I of Capua (her off and on again enemy), took to the field in support of a new pope, Victor III. In 1087, Matilda led an expedition to Rome in an attempt to install Victor, but the strength of the imperial counterattack soon convinced the pope to retire from the city.

Around 1090, Matilda married again, to Welf V of Bavaria, from a family (the Welfs) whose very name was later to become synonymous with alliance to the popes in their conflict with the German emperors (see Guelphs and Ghibellines). This forced Henry to return to Italy, where he drove Matilda into the mountains. He was humbled before Canossa, this time in a military defeat in October 1092, from which his influence in Italy never recovered.

In 1095, Henry attempted to reverse his fortunes by seizing Matilda's castle of Nogara, but the countess's arrival at the head of an army forced him to retreat. In 1097, Henry withdrew from Italy altogether, after which Matilda reigned virtually uncontested, although she did continue to launch military operations designed to restore her authority and regain control of the towns that had remained loyal to the emperor. She ordered or commanded successful expeditions against Ferrara (1101), Parma (1104), Prato (1107) and Mantua (1114). In 1111, at Bianello, she was made viceroy of Liguria by the Emperor Henry V.

Death and legacy

Matilda's death of gout in 1115 at Bondeno di Roncore marked the end of an era in Italian politics. It has been reported that she left her allodial property to the Pope for reasons not known however this donation was never officially recognized in Rome and no record has reached us. Henry had promised some of the cities in her territory he would appoint no successor after he deposed her. In her place the leading citizens of these cities took control, and the era of the city-states in northern Italy began. In the 17th century, her body was removed to the Vatican, where it now lies in St. Peter's Basilica.

The story of Matilda and Henry IV is the main plot device in Luigi Pirandello's play Enrico IV. She is the main historical character in Kathleen McGowan's novel The Book of Love (Simon & Schuster, 2009).

Foundation of churches

Traditionally, people say Matilda founded some churches; among those:

- Sant'Andrea Apostolo of Vitriola, at Montefiorino (MO)

- San Giovanni Decollato, at Pescarolo ed Uniti (CR)

- Santa Maria Assunta, at Monteveglio (BO)

- San Martino in Barisano, near Forlì

- San Zeno, at Cerea (VR).

Notes

References

- Hay, David (2008). The Military Leadership of Matilda of Canossa, 1046-1115. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Kahn Spike, Michéle (2004). Tuscan Countess: The Life and Extraordinary Times of Matilda of Canossa. New York: The Vendome Press.

- Eads, Valerie (2002). "The Geography of Power: Matilda of Tuscany and the Strategy of Active Defense". In L. J. Andrew Villalon and Donald Kagay. Crusaders, Condottieri and Cannon: Medieval Warfare in Societies around the Mediterranean. Leiden: Brill.

- Fraser, Antonia. The Warrior Queens. ISBN 0-679-72816-3.

- Duff, Nora (1909). Matilda of Tuscany: La Gran Donna d'Italia. London: Methuen & Co.

- Arturo Calzona (ed), Matilde e il tesoro dei Canossa: Tra castelli, monasteri e città (Cinisello Balsamo, Milano, Silvana Editoriale. 2008).

External links

- The Lands of Matilde of Canossa

"Matilda of Canossa". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Matilda of Canossa". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.- Women's Biography: Matilda of Tuscany, countess of Tuscany, duchess of Lorraine, contains several letters to and from Matilda.

Italian nobility Preceded by

Godfrey IVMargravine of Tuscany

1076–1115Succeeded by

Conrad von ScheiernCategories:- 1046 births

- 1115 deaths

- People from Lombardy

- Women of medieval Italy

- House of Canossa

- Duchesses of Lorraine

- Margraves of Tuscany

- 11th-century Italian people

- 12th-century Italian people

- Women in Medieval warfare

- Women in European warfare

- Burials at St. Peter's Basilica

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.