- 1999 Bridge Creek

-

"Moore, Oklahoma tornado" redirects here. For other uses, see Moore, Oklahoma tornado (disambiguation).

1999 Bridge Creek – Moore tornado An American Flag blows in the wind next to the remains of a home destroyed by the tornado Date: May 3, 1999 Time: 6:23 pm – 7:48 pm CDT Rating: F5 tornado Damages: $1 billion (1999 USD)

$1.3 billion (2011 USD)Casualties: 36 direct, 5 indirect (583 injuries) Area affected: Oklahoma; Grady, McClain, Cleveland and Oklahoma counties; particularly the cities of Bridge Creek and Moore The 1999 Bridge Creek – Moore tornado was an extremely powerful F5 tornado which devastated towns just outside of Oklahoma City on May 3, 1999. Throughout its one hour and 25 minute existence, the tornado covered 38 mi (61 km), destroying thousands of homes, killing 41 people and leaving $1 billion in losses behind. This ranks the tornado as the third costliest on record, not accounting for inflation.[1] The tornado first touched down at 6:23 pm CDT in Grady County, roughly 2 mi (3.2 km) south-southwest of Amber. It quickly intensified into a violent F4 system, and gradually reached F5 status after traveling 6.5 mi (10.5 km), at which time it struck the city of Bridge Creek. Once it moved through the city, it fluctuated between F2 and F5 status as it crossed into Cleveland County. Not long after entering the county, it reached F5 intensity for a third time as it moved through the city of Moore. By 7:30 pm CDT, the tornado crossed into Oklahoma County and battered southern Oklahoma City before dissipating around 7:48 pm CDT just outside Midwest City.

Contents

Meteorological synopsis

A map of the meteorological setup of the 1999 Oklahoma tornado outbreak. The map displays surface and upper level atmospheric features associated with the outbreak. Click on the map to enlarge.

A map of the meteorological setup of the 1999 Oklahoma tornado outbreak. The map displays surface and upper level atmospheric features associated with the outbreak. Click on the map to enlarge.

The Bridge Creek – Moore tornado was part of a much larger tornado outbreak which spawned 71 tornadoes across five states on May 3 alone.[2] On the morning of May 3, the Storm Prediction Center (SPC) stated that there was a slight risk for a severe weather event later that day as a dry line that stretched from western Kansas into western Texas approached a warm, humid air-mass over the Central Plains. Although cirrus clouds were present through much of the day, an eventual clearing allowed for the sun to heat up the moisture-laden region, creating significant atmospheric instability. By 7:00 am CDT, CAPE values began exceeding 4,000 j/kg, a level which climatologically favors the development of severe thunderstorms.[3] This prompted the SPC to upgrade the risk of severe weather to moderate for much of central Oklahoma.[4]

By the early afternoon hours, forecasters at both the SPC and National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma realized that a major event was likely to take place.[5] Conditions became highly conductive for tornadic development by 1:00 pm CDT as wind shear intensified over the region, creating a highly unstable atmosphere.[3] At 3:49 pm CDT, a high-risk of severe weather was issued for much of central Oklahoma.[6] Within minutes of this, supercells began developing over southwestern Oklahoma, prompting a severe thunderstorm warning by 4:15 pm CDT.[3]

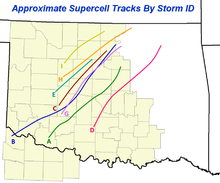

The thunderstorm that eventually spawned the F5 Bridge Creek – Moore tornado formed around 3:30 pm CDT over Tillman County. Tracking northeast, the storm strengthened and entered Comanche County shortly after 4:00 pm CDT.[7] There, hail up to 1.75 in (44 mm) in diameter fell;[8] at 4:51 pm CDT, the first of 14 tornadoes associated with supercell "A" touched down along U.S. Route 62. Five more tornadoes touched down as the storm continued northeast; the sixth touchdown was an F3 which caused substantial damage in Grady County. At 6:23 pm CDT, the ninth tornado associated with supercell "A" touched down about 2 mi (3.2 km) south-southwest of Amber.[7]

The tornado quickly intensified as it crossed Oklahoma State Highway 92, attaining F4 strength about 4 mi (6.4 km) east-northeast of Amber. This rating was sustained over the following 6.5 mi (10.5 km) before striking Bridge Creek. There, it attained the highest-possible rating on the Fujita Scale, F5. Two homes were completely destroyed, leaving only a concrete slab where the homes once were. About 1 in (25 mm) of asphalt was torn off a road by the violent tornado. Continuing northeastward, the tornado briefly weakened to F4 status before becoming an F5 again as it neared the Grady-McClain border where a car was thrown roughly 0.25 mi (0.40 km). At this time, it had attained a width of 1 mi (1.6 km).[7] Around 6:57 pm CDT, the first-ever tornado emergency was issued for the southern Oklahoma City Metro area.[9][10]

Paralleling Interstate 44, the tornado moved into McClain county where it crossed the highway twice at F4 intensity. At 7:10 pm CDT, a satellite tornado touched down over an open field north of Newcastle; it was rated as an F0 due to lack of damage. After crossing the Canadian River, the tornado entered Cleveland County and weakened to F2 intensity. By this time, it had entered the southern reaches of Oklahoma City. Several minutes after entering the county, it re-attained F4 status, destroying dozens of homes. Moving into the city of Moore, the tornado reached F5 intensity for a third time, leaving only concrete slabs where homes used to be.[7] At 7:30 pm CDT, the tornado crossed into Oklahoma County, passing through the industrial district.[11] After moving through Del City and Midwest City, the tornado crossed Interstate 40 where hundreds of cars were tossed up to 0.2 mi (0.32 km), some crashing into motels. Parts of the Rose State College campus were severely damaged as the tornado moved through; based on the damage, the tornado attained high-end F4 status, although F5 was considered as well. The tornado then began to rapidly dissipate as it moved through northeastern portion of the city. It finally lifted around 7:48 pm CDT just outside Midwest City. Throughout its one hour and 25 minute existence, the tornado tracked for 38 mi (61 km) across four counties.[7]

- Record

As the tornado moved into Oklahoma City, a mobile Doppler weather Radar estimated sustained winds within the tornado between 281 and 321 mph (452 and 517 km/h), the highest winds ever recorded at the time.[12] However, since the record for maximum winds are reported from only non-tornadic events, the 253 mph (407 km/h) wind gust from Cyclone Olivia in 1996 retained the title.[13]

Impact

Impact by county County Fatalities Injuries Damage Grady 12 39 $90 million McClain 1 17 $10 million Cleveland 11 293 $450 million Oklahoma 12 234 $450 million Unknown 5 Total 41 583 $1 billion Throughout the tornado's path, 36 people were killed as a direct result of the storm and five more died in the hours following it. According to the Department of Health, an estimated 583 people were injured by the tornado, accounting for those who likely did not go to the hospital or were unaccounted for.[7] In terms of structural lossess, a total of 8,132 homes, 1,041 apartments, 260 businesses, 11 public buildings and seven churches were damaged or destroyed.[14] Total losses from the tornado reached $1 billion, making it the only tornado to cause such damage on record.[7]

In Grady County, where the tornado first touched down, 12 people were killed and 39 others were injured. The tornado wrought catastrophic damage, especially in Bridge Creek, where the 1 mi (1.6 km) wide F5 system struck. Several homes were reduced to just concrete slabs and mobile homes were obliterated. Roughly 200 structures in the direct path of the tornado were completely destroyed. Twelve fatalities and most of the 39 injuries took place in the Willow Lake Addition, Southern Hills Addition, and Bridge Creek Estates of Bridge Creek, nine of which were in mobile homes. Losses in the county were estimated at $90 million.[15]

Throughout most of the tornado's track through McClain county, it paralleled Interstate 44, avoiding most populated areas. However, one person was killed after she was blown out of an overpass near Newcastle. In all, 17 people were injured, 40 structures were destroyed and 40 more were damaged. Losses in McClain were estimated at $10 million.[16]

Some of the most severe damage took place in Cleveland County, especially in the city of Moore, where 11 people were killed and 293 others were injured. The tornado wrought an estimated $450 million in damage across the county. The first area impacted in Cleveland was Country Place Estates where 50 homes were damaged and one was completely destroyed, with only the foundation remaining. Several vehicles were picked up and tossed nearly 0.25 mi (0.40 km). According to local police, an airplane wing, believed to have been from an airport in Grady County, was found near Country Place Estates. Next, the powerful tornado struck the densely populated Eastlake Estates at F5 intensity, killing three people and reducing entire rows of homes to rubble. In one instance, four adjacent homes were completely destroyed, with only concrete slabs remaining. In the Emerald Springs Apartments, three more people were killed and a two-story apartment was almost flattened.[17]

Just outside the Eastlake Estates, a ceremony at Westmoore High School was behing held at the time of the tornado; however, adequate warning time allowed everyone to seek shelter and no injures took place at the ceremony. Ultimately, the school sustained heavy damage and dozens of cars in the parking lot were tossed around, many of which were destroyed. The tornado proceeded into the western city limits of Moore shortly thereafter. Near Janeway, four people were killed in an area where large sections of homes were completely destroyed. Afterwords, the tornado moved through a relatively sparsely populated area of Moore before entering Oklahoma County.[17]

Aftermath

Following the outbreak of deadly and destructive tornadoes, President Bill Clinton signed a major disaster declaration for 11 counties in Oklahoma on May 4. In a press statement by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), director James Lee Witt stated that "The President is deeply concerned about the tragic loss of life and destruction caused by these devastating storms."[18] The American Red Cross opened ten shelters overnight, housing 1,600 people immediately following the disaster. By May 5, this number had lowered to 500. Throughout May 5, several post-disaster teams from FEMA were deployed to the region, including emergency response and preliminary damage assessment. The United States Department of Defense deployed the 249th Engineering Battalion and placed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on standby for assistance. Medical and mortuary teams were also sent by the Department of Health and Human Services.[19] By May 6, donation centers and phone banks were being established to create funds for victims of the tornadoes.[20]

Continuing search and rescue efforts for 13 people who were listed as missing through May 7 were assisted by urban search and rescue dogs from across the country.[21] Nearly 1,000 members of the Oklahoma National Guard were deployed throughout the affected region. The American Red Cross had set up ten mobile feeding stations by this time and stated that 30 more were en route.[22] On May 8, a disaster recovery center was opened in Moore for individuals recovering from the tornadoes.[23] According to the Army Corps of Engineers, roughly 500,000 cubic yards (382,277 cubic meters) of debris was left behind and would likely take weeks to clear.[24] Within the first few days of the disaster declaration, relief funds began being sent to families who requested aid. By May 9, roughly $180,000 had been approved by FEMA for disaster housing assistance.[25]

Debris removal finally began on May 12 as seven cleanup teams were sent to the region, more were expected to join over the following days.[26] That day, FEMA also declared that seven counties, Canadian, Craig, Grady, Lincoln, Logan, Noble and Oklahoma, were eligible for federal financial assistance.[27] By May 13, roughly $1.6 million in disaster funds had been approved for housing and businesses loans.[28] This quickly rose to more than $5.9 million over the following five days.[29] By May 21, more than 3,000 volunteers from across the country traveled to Oklahoma to help residents recover; 1,000 of these volunteers were sent to Bridge Creek to clean up debris, cut trees, sort donations and cook meals.[30] With a $452,199 grant from FEMA, a 60-day outreach program for victims suffering tornado-related stress was set up to help them deal cope with trauma.[31]

Applications for federal aid continued through June, with state approvals reaching $54 million on June 3. By this date, the Army Corps of Engineers reported that 964,170 cubic yards (737,160 cubic meters), roughly 58%, of the 1.65 million cubic yards (1.26 million cubic meters) of debris had been removed.[32] Assistance for farmers and ranchers who suffered severe losses from the tornadoes was also available by June 3.[33] After more than a month of being open, emergency shelters were set to be closed on June 18.[34] On June 21, an educational road show made by FEMA visited the hardest hit areas in Oklahoma to urge residents to build storm cellars.[35] According to FEMA, more than 9,500 residents applied for federal aid during the allocated period in the wake of the tornadoes. Most of the applicants lived in Oklahoma and Cleveland counties, 3,800 and 3,757 persons respectively. In all, disaster recovery aid for the tornadoes amounted to roughly $67.8 million by the end of July 2.[36]

From a meteorological and safety standpoint, the tornado also brought the use of highway overpasses as shelters into question. Prior to the events on May 3, 1999, videos of people taking shelter in overpasses during tornadoes in the past gave the public misunderstanding that overpasses provided shelter from tornadoes. For nearly 20 years, meteorologists had questioned the safety of these structures; however, they lacked incidents involving loss of life.[37] During the May 3 outbreak, three overpasses were directly struck by tornadoes, with a fatality taking place at each one. Two of these were from the F5 Bridge Creek – Moore tornado while the third was from a small, F2 which struck a rural area north of Oklahoma City.[38] According to a study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, seeking shelter in an overpass "is to become a stationary target for flying debris."[39]

Over the following four years, a $12 million project to construct storm shelters for residents across Oklahoma City was enacted. The goal was to create a safer community in a tornado-prone region. By May 2003, a total of 6,016 safe rooms were constructed. On May 9, 2003, the new initiative was put to the test as a tornado outbreak in the region spawned an F4 tornado which took a path similar to that of the Bridge Creek – Moore tornado. Due to the higher standards for public safety, no one was killed by the tornado in 2003, a substantial improvement in just four years.[40]

See also

References

- ^ Storm Prediction Center (2007). "The 10 Costliest U.S. Tornadoes since 1950". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.spc.noaa.gov/faq/tornado/damage$.htm. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ "NCDC Storm Events Database". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. http://www4.ncdc.noaa.gov/cgi-win/wwcgi.dll?wwevent~storms. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Meteorological Summary of the Great Plains Tornado Outbreak of May 3–4, 1999". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. May 3, 2010. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/oun/?n=events-19990503-summary. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "Severe Weather Outlook for 11:15 am CDT". Storm Prediction Center. May 3, 1999. http://www.spc.noaa.gov/publications/edwards/3mf5c.gif. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ James Murnan (April 20, 2009). "Remembering May 3, 1999". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.norman.noaa.gov/2009/04/remembering-may-3-1999/. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "Severe Weather Outlook for 3:49 am CDT". Storm Prediction Center. May 3, 1999. http://www.spc.noaa.gov/publications/edwards/3mf5d.gif. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Great Plains Tornado Outbreak of May 3–4, 1999: Storm A Information". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. May 3, 2010. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/oun/?n=events-19990503-storma. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "Oklahoma Event Report: Hail". National Climatic Data Center. 2000. http://www4.ncdc.noaa.gov/cgi-win/wwcgi.dll?wwevent~ShowEvent~368768. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "South Oklahoma Metro Tornado Emergency". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. May 3, 1999. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/images/oun/wxevents/19990503/tornadoemergency.png. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "May 3rd, 1999 from the NWS's Perspective". The Southern Plains Cyclone (National Weather Service) 2 (2). Spring 2004. Archived from the original on 2004-11-08. http://replay.waybackmachine.org/20041108065124/http://www.srh.noaa.gov/oun/newsletter/spring2004/#19990503. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ^ "Oklahoma Event Report: F4 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. 2000. http://www4.ncdc.noaa.gov/cgi-win/wwcgi.dll?wwevent~ShowEvent~368827. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "Doppler On Wheels". Center for Severe Weather Research. 2010. http://cswr.org/dow/DOW.htm. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "Highest surface wind speed - Tropical Cyclone Olivia sets world record". World Record Academy. January 26, 2010. http://www.worldrecordsacademy.org/weather/highest_surface_wind_speed_Tropical_Cyclone_Olivia_sets_world_record_101519.htm. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ "The 1999 Oklahoma Tornado Outbreak: 10-Year Retrospective" (PDF). Risk Management Solutions. 2009. http://www.rms.com/Publications/1999_Oklahoma_Tornado_Outbreak.pdf. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Oklahoma Event Report: F5 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. 2000. http://www4.ncdc.noaa.gov/cgi-win/wwcgi.dll?wwevent~ShowEvent~368806. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Oklahoma Event Report: F4 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. 2000. http://www4.ncdc.noaa.gov/cgi-win/wwcgi.dll?wwevent~ShowEvent~368816. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "Oklahoma Event Report: F5 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. 2000. http://www4.ncdc.noaa.gov/cgi-win/wwcgi.dll?wwevent~ShowEvent~368820. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "President Declares Major Disaster for Oklahoma". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 4, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9737. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Oklahoma/Kansas Tornado Disaster Update". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 5, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9689. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Plains States Tornado Update". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 6, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9688. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "FEMA Sends Urban Search & Rescue Dogs to Oklahoma". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 7, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9735. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Plains States Tornado Disaster Update". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 7, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9687. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "FEMA and State Open Disaster Recovery Center in Moore". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 7, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9728. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Debris Removal Begins; Army Corps of Engineers Targets Public Access and Property". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 7, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9727. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "First Checks Approved for Oklahoma Storm Victims". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 9, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9726. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Debris Removal Underway in Oklahoma City, Mulhall, and Choctaw; Stroud Set for Thursday". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 12, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9731. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Seven Oklahoma Counties Get Expanded Disaster Assistance". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 12, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9730. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Oklahoma Tornado Disaster Update". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 13, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9732. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Oklahoma Disaster Recovery News Summary". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 18, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9717. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Flood of Volunteers Aids Tornado Victims". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 21, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9712. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Help Available To Those Coping With Tornado-Related Stress". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 21, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9710. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Oklahoma Disaster Aid Tops $54 Million". Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 3, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9704. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Disaster Assistance is Available to Oklahoma Farmers and Ranchers". Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 3, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9703. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ "Disaster Recovery Centers To Close In Bridge Creek And Dover". Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 14, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9698. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ "Safe Room Show Visits Oklahoma". Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 21, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9696. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ "Almost 9,500 Oklahomans Register For Disaster Recovery Aid More Than $67.8 Million In Grants And Loans Approved". Federal Emergency Management Agency. July 7, 1999. http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=9694. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ Daniel J. Miller, Charles A. Doswell III, Harold E. Brooks, Gregory J. Stumpf and Erik Rasmussen (1999). "Highway Overpasses as Tornado Shelters". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. p. 1. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/oun/?n=safety-overpass-slide01. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ Daniel J. Miller, Charles A. Doswell III, Harold E. Brooks, Gregory J. Stumpf and Erik Rasmussen (1999). "Highway Overpasses as Tornado Shelters: Events on May 3, 1999". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. p. 5. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/oun/?n=safety-overpass-slide05. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ Daniel J. Miller, Charles A. Doswell III, Harold E. Brooks, Gregory J. Stumpf and Erik Rasmussen (1999). "Highway Overpasses as Tornado Shelters: Highway Overpasses Are Inadequate Tornado Sheltering Areas". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. p. 6. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/oun/?n=safety-overpass-slide06. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ "Residents Survive May 2003 Tornado". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 9, 2003. http://www.fema.gov/mitigationbp/brief.do?mitssId=500. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

External links

- The Great Plains Tornado Outbreak of May 3-4, 1999

- FEMA: Oklahoma Tornadoes, Severe Storms, and Flooding

10 costliest US tornadoes Rank Area affected Date Damage 1 Adjusted Damage 2 1 Joplin, Missouri May 22, 2011 2800 2800 2 Tuscaloosa, Alabama April 27, 2011 2200 2200 3 Oklahoma City Metro, Oklahoma May 3, 1999 1000 1318 4 Hackleburg, Alabama April 27, 2011 1250 1250 5 Wichita Falls, Texas April 10, 1979 400 1209 6 Omaha, Nebraska May 6, 1975 250 1019 7 Lubbock, Texas Tornado May 11, 1970 135 763 8 Topeka, Kansas Tornado June 8, 1966 100 676 9 Windsor Locks, Connecticut October 3, 1979 200 605 10 St. Louis-East St. Louis Tornado May 27, 1896 12 520

Source: Brooks, Harold E.; C.A. Doswell (Feb 2001). "Normalized Damage from Major Tornadoes in the United States: 1890–1999". Weather and Forecasting (American Meteorological Society) 16 (1): 168-76. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2001)016<0168:NDFMTI>2.0.CO;2. http://ams.allenpress.com/perlserv/?request=get-abstract&doi=10.1175%2F1520-0434(2001)016%3C0168%3ANDFMTI%3E2.0.CO%3B2. 3

1. These are the unadjusted damage totals in millions of US dollars.

2. Raw damage totals adjusted for inflation, in millions of 2011 USD.

3. A search of NCDC Storm Data indicates no tornadoes between 1999 and 2010 have caused more than $250 million in damage.Categories:- F5 tornadoes

- Tornadoes in Oklahoma

- 1999 in the United States

- Tornadoes of 1999

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.