- Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573)

-

Fourth Ottoman–Venetian War Part of the Ottoman–Venetian Wars

The Battle of LepantoDate 1570–1573 Location Cyprus, Ionian and Aegean Seas Result Ottoman victory Territorial

changesCyprus under Ottoman rule Belligerents  Republic of Venice

Republic of Venice

Spain

Spain

Papal States

Papal States

Republic of Genoa

Republic of Genoa

Duchy of Savoy

Duchy of Savoy

Knights of Malta

Knights of Malta Ottoman Empire

Ottoman EmpireCommanders and leaders  Marco Antonio Bragadin

Marco Antonio Bragadin

Alvise Martinengo

Alvise Martinengo

Sebastiano Venier

Sebastiano Venier

Don John of Austria

Don John of Austria

Marcantonio Colonna

Marcantonio Colonna

Giovanni Andrea Doria

Giovanni Andrea Doria

Jacopo Soranzo

Jacopo Soranzo Piyale Pasha

Piyale Pasha

Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha

Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha

Müezzinzade Ali Pasha †

Müezzinzade Ali Pasha †

Kılıç Ali Pasha

Kılıç Ali PashaThe Fourth Ottoman–Venetian War, also known as the War of Cyprus (Italian: Guerra di Cipro) was fought between 1570–1573. It was waged between the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Venice, the latter joined by the Holy League, a coalition of Christian states formed under the auspices of the Pope, which included Spain (with Naples and Sicily), the Republic of Genoa, the Duchy of Savoy, the Knights Hospitaller, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and other Italian states.

The war, the preeminent episode of Sultan Selim II's reign, began with the Ottoman invasion of the Venetian-held island of Cyprus. The capital Nicosia and several other towns fell quickly to the considerably superior Ottoman army, leaving only Famagusta in Venetian hands. Christian reinforcements were delayed, and Famagusta eventually fell in August 1571 after a siege of 11 months. Two months later, at the Battle of Lepanto, the united Christian fleet destroyed the Ottoman fleet, but was unable to take advantage of this victory. The Ottomans quickly rebuilt their naval forces, and Venice was forced to negotiate a separate peace, ceding Cyprus to the Ottomans and paying a tribute of 300,000 ducats.

Contents

Background

The large and wealthy island of Cyprus had been under Venetian rule since 1489. Together with Crete, it was one of the major overseas possessions of the Republic. Its population in the mid-16th century is estimated at 160,000.[1] Aside from its location, which allowed the control of the Levantine trade, the island possessed a profitable production of cotton and sugar.[2] To safeguard their most distant colony, the Venetians paid an annual tribute of 8,000 ducats to the Mamluk Sultans of Egypt, and after their fall to the Ottomans in 1517, the agreement was renewed with the Porte.[3][4] Nevertheless, the island's strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean, between the Ottoman heartland of Anatolia and the newly won provinces of the Levant and Egypt, made it a tempting target for future Ottoman expansion.[5][6] In addition, the protection offered by the local Venetian authorities to Christian corsairs who harassed Muslim shipping, including the pilgrims to Mecca, rankled with the Ottoman leadership.[7][8]

After concluding a prolonged war with the Habsburgs in 1568, the Ottomans were free to turn their attention to Cyprus.[9] Sultan Selim II had made the conquest of the island his first priority already before his accession in 1566, relegating Ottoman aid of the Morisco Revolt against Spain and attacks against Portuguese activities in the Indian Ocean to a secondary priority.[10] Despite the peace treaty with Venice, renewed as recently as 1567,[8][11] and the opposition of Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, the war party at the Ottoman court prevailed.[7] A favorable juridical opinion by the Sheikh ul-Islam was secured, which declared that the breach of the treaty was justified since Cyprus was a "former land of Islam" (briefly in the 7th century) and had to be retaken.[8][12] Money for the campaign was raised by the confiscation and resale of monasteries and churches of the Greek Orthodox Church.[13] The Sultan's old tutor, Lala Mustafa Pasha, was appointed as commander of the expedition's land forces.[14] Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, although totally inexperienced in naval matters, was appointed as Kapudan Pasha; he, however, assigned the able and experienced Piyale Pasha as his principal aide.[15]

On the Venetian side, Ottoman intentions had been clear, and an attack against Cyprus had been anticipated for some time. A war scare had broken out in 1564–1565, when the Ottomans eventually sailed for Malta, and unease mounted again in late 1567 and early 1568, as the scale of the Ottoman naval buildup became apparent.[16] The defenses of Cyprus, Crete, Corfu and other Venetian possessions were upgraded in the 1560s, employing the services of the noted military engineer Sforza Pallavicini. Their garrisons were increased, and attempts were made to make the isolated holdings of Crete and Cyprus more self-sufficient by the construction of foundries and gunpowder mills.[17] However, it was widely recognized that, unaided, Cyprus could not hold for long.[9] Its exposed and isolated location so far from Venice, surrounded by Ottoman territory, put it "in the wolf's mouth" as one contemporary historian wrote.[18] In the event, lack of supplies and even gunpowder would play a critical role in the fall of the Venetian forts to the Ottomans.[18] Another problem for Venice was the attitude of the island's population. The harsh treatment and oppressive taxation of the local orthodox Greek population by the Catholic Venetians had caused great resentment, so that their sympathies generally laid with the Ottomans.[19]

By early 1570, the Ottoman preparations and the warnings sent by the Venetian bailo at Constantinople, Marco Antonio Barbaro, had convinced the Signoria that war was imminent. Reinforcements and money were sent post-haste to Crete and Cyprus.[20] In March 1570, an Ottoman envoy was sent to Venice, bearing an ultimatum that demanded the immediate cession of Cyprus.[9] Although some voices were raised in the Venetian Signoria advocating the cession of the island in exchange for land in Dalmatia and further trading privileges, the hope of assistance from the other Christian states stiffened the Republic's resolve, and the ultimatum was categorically rejected.[21]

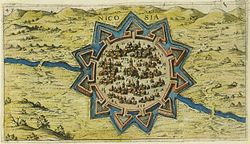

Ottoman conquest of Cyprus

Main article: Ottoman CyprusOn 27 June, the invasion force, some 350 ships and 60,000 men, set sail for Cyprus. It landed unopposed at Salines,near Larnaca on the island's southern shore on 3 July, and marched towards the capital, Nicosia.[22] The Venetians had debated opposing the landing, but in the face of the superior Ottoman artillery, and the fact that a defeat would mean the annihilation of the island's defensive force, it was decided to withdraw to the forts and hold out until reinforcements arrived.[23] The Siege of Nicosia began on 22 July and lasted for seven weeks, until 9 September.[22] The city's newly constructed trace italienne walls of packed earth withstood the Ottoman bombardment well. The Ottomans, under Lala Mustafa Pasha, dug trenches towards the walls, and gradually filled the surrounding ditch, while constant volleys of arquebus fire covered the sappers' work.[24] Finally, the 45th assault, on 9 September, succeeded in breaching the walls after the defenders had exhausted their ammunition. A massacre of the city's 20,000 inhabitants ensued.[25] Even the city's pigs, regarded as unclean by Muslims, were killed, and only women and boys who were captured to be sold as slaves were spared.[24] A combined Christian fleet of 200 vessels, composed of Venetian (under Girolamo Zane), Papal (under Marcantonio Colonna) and Neapolitan/Genoese/Spanish (under Giovanni Andrea Doria) squadrons that had belatedly been assembled at Crete by late August and was sailing towards Cyprus, turned back when it received news of Nicosia's fall.[21][26]

Following the fall of Nicosia, the fortress of Kyrenia in the north surrendered without resistance, and on 15 September, the Turkish cavalry appeared before the last Venetian stronghold, Famagusta. At this point already, overall Venetian losses (including the local population) were estimated by contemporaries at 56,000 killed or taken prisoner.[27] The Venetian defenders of Famagusta numbered about 8,500 men with 90 artillery pieces and were commanded by Marco Antonio Bragadin. They would hold out for 11 months against a force that would come to number 200,000 men, with 145 guns,[28] providing the time needed by the Pope to cobble together an anti-Ottoman league from the reluctant Christian European states.[29] The Ottomans set up their guns on 1 September.[25] Over the following months, they proceeded to dig a huge network of crisscrossing trenches for a depth of three miles around the fortress, which provided shelter for the Ottoman troops. As the siege trenches neared the fortress and came within artillery range of the walls, ten forts of timber and packed earth and bales of cotton were erected.[30] The Ottomans however lacked the naval strength to completely blockade the city from sea as well, and the Venetians were able to resupply it and bring in reinforcements. After news of such a resupply in January reached the Sultan, he recalled Piyale Pasha and left Lala Mustafa alone in charge of the siege.[31] At the same time, an initiative by Sokollu Mehmed Pasha to achieve a separate peace with Venice, foundered.[32] Thus on 12 May 1571, the intensive bombardment of Famagusta's fortifications began, and on 1 August, with ammunition and supplies exhausted, the garrison surrendered the city.[30] The siege cost the Ottomans some 50,000 casualties.[33]

The Holy League

As the Ottoman army campaigned in Cyprus, Venice tried to find allies. The Holy Roman Emperor, having just concluded peace with the Ottomans, was not keen to break it. France was traditionally on friendly terms with the Ottomans and hostile to the Spanish, and the Poles were troubled by Muscovy.[34] The Spanish Habsburgs, the greatest Christian power in the Mediterranean, were not initially interested in helping the Republic and resentful of Venice's refusal to send aid during the Siege of Malta in 1565.[9][35] In addition, Philip II of Spain wanted to focus his strength against the Barbary states of North Africa. The Spanish reluctance to engage on the side of the Republic, together with Doria's reluctance to endanger his fleet, had already disastrously delayed the joint naval effort in 1570.[27] However, with the energetic mediation of Pope Pius V, an alliance against the Ottomans, the "Holy League", was concluded on 15 May 1571, which stipulated the assembly of a fleet of 200 galleys, 100 supply vessels and a force of 50,000 men. To secure Spanish assent, the treaty also included a Venetian promise to aid Spain in North Africa.[9][21][36]

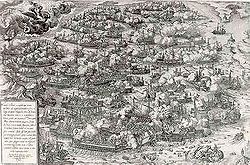

Lepanto and the failure of the League

According to the terms of the new alliance, during the late summer, the Christian fleet assembled at Messina, under the command of Don John of Austria, who arrived on 23 August. By that time, however, Famagusta had fallen, and any effort to save Cyprus was meaningless.[21] However, as it was sailing down the Ionian Sea, the combined Christian fleet came upon the Ottoman fleet, commanded by Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, which had anchored at Lepanto (Nafpaktos), near the entrance of the Corinthian Gulf.[37]

On 7 October, the two fleets engaged in a battle off Lepanto, which resulted in a crushing victory for the Christian fleet, while the Ottoman fleet was largely destroyed.[38] In popular perception, the battle itself became known as one of the decisive turning points in the long Ottoman-Christian struggle, as it ended the Ottoman naval hegemony established at the Battle of Preveza in 1538.[9] Its immediate results however were minimal:[39] the harsh winter that followed precluded any offensive actions on behalf of the Holy League, while the Ottomans used the respite to feverishly rebuild their naval strength. At the same time, Venice suffered losses in Dalmatia, where the Ottomans advanced, taking several inland positions and the island of Brazza (Brač). The strategic situation was graphically summed up later by the Ottoman Grand Vizier to the Venetian bailo: "[in defeating our fleet] you have shaved our beard, but it will grow again, but [in conquering Cyprus] we have severed your arm and you will never find another."[40]

The following year, as the allied Christian fleet resumed operations, it faced a renewed Ottoman navy under Kılıç Ali Pasha.[41] Both fleets cruised and skirmished repeatedly off the Peloponnese, but no decisive engagement resulted. The diverging interests of the League members began to show, and the alliance began to fail. In 1573, the Holy League fleet failed to sail altogether; instead, Don John attacked and took Tunis, although retaken by the Ottomans in 1574.[42] Venice, eager to cut her losses and resume the trade with the Ottoman Empire, initiated unilateral negotiations with the Porte.[41][43]

Peace settlement and aftermath

Marco Antonio Barbaro, the Venetian bailo who had been imprisoned since 1570, conducted the negotiations. In view of the Republic's inability to regain Cyprus, the resulting treaty, signed on 7 March 1573, confirmed the new state of affairs: Cyprus became an Ottoman province, Venice paid an indemnity of 300,000 ducats, and the Dalmatian border between the two powers was restored to its 1570 status quo ante.[41] Peace would continue between the two states until 1645, when a long war over Crete would break out.[44] Cyprus itself remained under Ottoman rule until 1878, when it was ceded to Britain as a protectorate. Ottoman suzerainty continued until the outbreak of World War I, when the island was annexed by Britain, becoming a crown colony in 1925.[45]

Notes

- ^ McEvedy & Jones (1978), p. 119

- ^ Faroqhi (2004), p. 140

- ^ Finkel (2006), pp. 113, 158

- ^ Cook (1976), p. 77

- ^ Setton (1984), p. 200

- ^ Goffman (2002), p. 155

- ^ a b Finkel (2006), p. 158

- ^ a b c Cook (1976), p. 108

- ^ a b c d e f Finkel (2006), p. 160

- ^ Faroqhi (2004), pp. 38, 48

- ^ Setton (1984), p. 923

- ^ Finkel (2006), pp. 158–159

- ^ Finkel (2006), p. 159

- ^ Goffman (2002), p. 156

- ^ Finkel (2006), pp. 159–160

- ^ Setton (1984), pp. 925–931

- ^ Setton (1984), pp. 907–908

- ^ a b Setton (1984), p. 908

- ^ Goffman (2002), pp. 155–156

- ^ Setton (1984), pp. 945–946, 950

- ^ a b c d Cook (1976), p. 109

- ^ a b Turnbull (2003), p. 57

- ^ Setton (1984), p. 991

- ^ a b Turnbull (2003), p. 58

- ^ a b Hopkins (2007), p. 82

- ^ Setton (1984), pp. 981–985

- ^ a b Setton (1984), p. 990

- ^ Turnbull (2003), pp. 58–59

- ^ Hopkins (2007), pp. 87–89

- ^ a b Turnbull (2003), pp. 59–60

- ^ Hopkins (2007), pp. 82–83

- ^ Hopkins (2007), pp. 83–84

- ^ Goffman (2002), p. 158

- ^ Setton (1984), p. 963

- ^ Setton (1984), pp. 941–943

- ^ Hopkins (2007), pp. 84–85

- ^ Turnbull (2003), p. 60

- ^ Finkel (2006), pp. 160–161

- ^ Faroqhi (2004), p. 38

- ^ Cowley & Parker (2001), p. 263

- ^ a b c Finkel (2006), p. 161

- ^ Finkel (2006), pp. 161–162

- ^ Faroqhi (2004), p. 4

- ^ Finkel (2006), p. 222

- ^ Borowiec (2000), pp. 19–21

Sources

- Borowiec, Andrew (2000). Cyprus: a troubled island. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96533-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=hzEDg6-d80MC.

- M. A., ed (1976). A History of the Ottoman Empire to 1730: Chapters from the Cambridge History of Islam and the New Cambridge Modern History. Cambridge University Press Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-09991-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=nUs7AAAAIAAJ.

- Cowley, Robert; Parker, Geoffrey (2001). The Reader's Companion to Military History. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0618127429.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya (2004). The Ottoman Empire and the World Around It. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-715-4.

- Finkel, Caroline (2006). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300–1923. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6112-2.

- Goffman, Daniel (2002). The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45908-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=3uJzjatjTL4C.

- Greene, Molly (2000). A Shared World: Christians and Muslims in the Early Modern Mediterranean. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00898-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=Ecy575SBY1cC.

- Hopkins, T. C. F. (2007). Confrontation at Lepanto: Christendom Vs. Islam. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0765305398. http://books.google.com/books?id=4a6ZetIufKcC.

- Lane, Frederic Chapin (1973). Venice, a Maritime Republic. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-1460-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=PQpU2JGJCMwC.

- McEvedy, Colin; Jones, Richard (1978). Atlas of World Population History. Penguin. http://books.google.com/books?id=WZkYAAAAIAAJ.

- Nicolle, David (1989). The Venetian Empire, 1200–1670 (Men-at-Arms Series #210). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0850458992. http://books.google.com/books?id=WuwULNmr2_cC.

- Rodgers, William Ledyard (1967). Naval Warfare Under Oars, 4th to 16th Centuries: A Study of Strategy, Tactics and Ship Design. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0870214875.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1984). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Vol. III: The Sixteenth Century. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87169-161-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=EgQNAAAAIAAJ.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1984). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Vol. IV: The Sixteenth Century. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87169-162-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=SrUNi2m_qZAC.

- Shaw, Stanford Jay; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Vol. 1: Empire of the Gazis – The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire, 1280–1808. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=E9-YfgVZDBkC.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003). The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699 (Essential Histories Series #62). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0415969130.

Categories:- 1570s conflicts

- History of Cyprus

- Wars involving the Knights Hospitaller

- Ottoman–Venetian Wars

- Wars involving the Papal States

- Wars involving Spain

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.