- Criminal Tribes Act

-

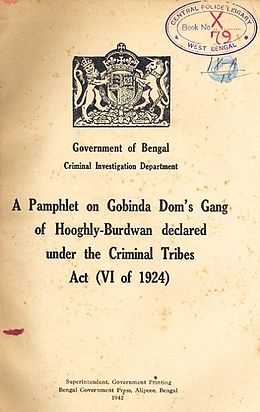

A Government of Bengal, CID pamphlet, on Gobinda Doms Gang, under the Criminal Tribes Act (VI of 1924), dated 1942.[1]

A Government of Bengal, CID pamphlet, on Gobinda Doms Gang, under the Criminal Tribes Act (VI of 1924), dated 1942.[1]

The term Criminal Tribes Act (CTA) applies to various successive pieces of legislation enforced in India during British rule; the first enacted in 1871 as Criminal Tribes Act (Act XXVII of 1871) applied mostly in North India[2]. The Act was extended to Bengal Presidency and other areas in 1876, and finally with the Criminal Tribes Act 1911, it was extended to Madras Presidency as well. The Act went through several amendments in the next decade and finally the Criminal Tribes Act (VI of 1924) incorporated all of them.[3]

The Act came into force, with the assent of the Governor-General of India on October 12, 1871.[4] Under the act, ethnic or social communities in India which were defined as "addicted to the systematic commission of non-bailable offenses" such as thefts, were systematically registered by the government. Since they were described as 'habitually criminal', restrictions on their movements were also imposed; adult male members of such groups were forced to report weekly to the local police.[5]

At the time of Indian independence in 1947, there were thirteen million people in 127 communities who faced constant surveillance, search and arrest without warrant if any member of the group was found outside the prescribed area [6]. Eventually the Act was repealed in August 1949 and former "criminal tribes" were denotified in 1952, when the Act was replaced with the Habitual Offenders Act 1952 of Government of India, and in 1961 state governments started releasing lists of such tribes.[7][8],

Today, there are 313 Nomadic Tribes and 198 Denotified tribes of India,[7][8] yet the legacy of the Act continues to haunt the majority of 60 million people belonging to these tribes, especially as their notification over a century ago has meant not just alienation and stereotyping by the police and the media, but also economic hardships. A large number of them can still only subscribe to a slightly altered label, "Vimukta jaatis" or the Ex-Criminal Tribes [9][10][11].

Contents

Reasons

A group of thugs, ca. 1863, a cult which harassed the British authorities. Many legends were created about them, including the idea of Born Criminals[12]

A group of thugs, ca. 1863, a cult which harassed the British authorities. Many legends were created about them, including the idea of Born Criminals[12]

Though ostensibly the law was created to bring into account groups like the Thugs which were successfully tackled in previous decades, and give the authorities better means to tackle the menace of 'professional criminals', many scholars believe, however, that this was also done due to their participation in the revolt of 1857, and many tribal chiefs were labeled traitors and caused constant trouble to the authorities through their frequent acts of rebellion [13].

Some historians, like David Arnold, have suggested that it so happened because many of these tribes were simply small communities of low-caste and nomadic people living on the fringes of the society upon rudimentary subsistence, often wandering to survive as petty traders, pastoralists, gypsies, hill and forest dwelling tribes, which did not conform to the British colonial idea of civilized living, of settled agriculture and waged labour. The trouble came, however, when criminality or professional criminal behaviour was taken to be hereditary rather than habitual, that is when crime became ethnic, and what was merely social determinism till then became biological determinism.[14][15]

This shift in notion seems to have arisen out of the prevalent belief in 19th century Europe that peripatetic lifestyles usually meant a menace to the society, hence termed as 'dangerous classes' and best kept under control or at least surveillance. Elsewhere the concept of reformatory schools for such people had already been initiated by mid-19th century by social reformers[16][17].

Moreover, India posed a unique problem to the colonialists as demarcation between wandering criminal tribes (Thugs, vagrants, itinerants, travelling tradesmen, nomads and gypsies) seemed impossible, so they were all, even eunuchs (hijras), grouped together, and their subsequent generations were merely a "law and order problem" for the state [17][18].

History

Intensive research on the issue shows that about 150 years ago, a large number of tribal communities were still nomadic, and were considered useful, honourable people by members of the settled societies with whom they came into regular contact.[citation needed] A number of them were small itinerant traders who used to carry their wares on the backs of their cattle, and bartered their goods in the villages through which they passed.[citation needed] They would bring interesting items to which people of a particular village and a little further away - spices, honey, grain of different varieties, medicinal herbs, different kinds of fruit or vegetables which the region did not grow, and so on.[citation needed]

Almost invariably, nomadic people were craftsmen of some kind or the other and in addition to their trading activity they would make and sell all sorts of useful little items like mats and baskets, brooms and brushes or earthenware utensils.[citation needed] Some like the Banjaras or Lambadis functioned on a larger scale, and moved in larger groups with pack animals loaded mainly with salt, and their women in addition to the salt also bartered the exquisitely crafted silver trinkets with settled villagers.[citation needed]

Some nomadic communities also became cattle traders, herdspeople or sellers of milk products, since they bred their own cattle for carrying their merchandise.[citation needed] The nomadic communities were not just useful to the villagers on a day to day basis — they were also acknowledged for averting the frequent grain shortages and famine like conditions in villages where crops failed.[citation needed] In addition, among them were musicians, acrobats, dancers, tightrope walkers, jugglers and fortune tellers. On the whole, they were considered a welcome and colourful change in routine whenever they visited or camped near a village.[citation needed]

There were several reasons for these communities first becoming gradually marginalised, and finally beginning to be considered useless to the settled societies.[citation needed] First, the network of roads and railways established in the 1850s connected many of the earlier outlying villages to each other as also to cities and towns.[citation needed]

The scale of the operations of the nomadic traders was thus drastically cut down to only those areas where wheel traffic could not yet reach.[citation needed] This was the single most important reason for the loss of livelihood of a number of nomadic communities.[citation needed] Further, under newly imposed forest laws, the British government did not allow tribal communities to graze their cattle in the forests, or to collect bamboo and leaves either, which were needed for making simple items like mats and baskets for their own use and for selling.[citation needed] These two developments had disastrous consequences for the nomadic traders.[citation needed]

There was one other major historical factor responsible for the impoverishment of a very large number of nomadic communities.[citation needed] The nineteenth century witnessed repeated severe famines - during each successive one the nomadic communities lost more and more heads of cattle which were the only means of transporting their goods to the interior villages.[citation needed] The cattle were in fact becoming more crucial than ever, as with increasing network of roads and railways these communities had to travel longer distances to sell their wares. Loss of cattle meant loss of trading activity on an unprecedented scale.[citation needed]

The British government gradually began to consider nomadic communities prone to criminality in the absence of legitimate means of livelihood.[citation needed] There was a parallel process[who?] taking place all along.[citation needed] A number of tribal chiefs, especially in the north, participated in the 1857 events, and earned the title of traitors and renegades with the British government.[citation needed] Elsewhere, hill tribes determinedly resisted the attempts by the British to annexe their land for establishing plantations, and to try and use them as plantation labour.[citation needed] A number of tribal communities, thus, would not yield to the British armed forces and consistently fought back, though whole habitations were burnt down in retaliation by the frustrated British officers deputed to co-opt them. Generally, it began to be felt that most tribal communities[citation needed], including nomadic ones, were dangerously criminal.[citation needed] The Criminal Tribes Act was born in these historical circumstances.[citation needed][original research?]

A large number of communities were officially declared criminal tribes from 1871 onwards. The British government subsequently ran special settlements for them where they[who?] were chained, shackled, caned and flogged while being surrounded by high walls under the provisions of the Criminal Tribes Act. In the name of the homegrown science of "curocriminology"[citation needed] it was declared that they would be cured of their criminal propensities if they were given work and such an understanding had an obvious corollary: the more they work, the more reformed they would be.[improper synthesis?] They could be thus forced to work for up to 20 hours a day in factories, plantations, mills, quarries and mines all through the first few decades of the twentieth century. This was an era when the Factories Act had come into existence, but the British employers were officially[citation needed] able to do away with those provisions of the Factories Act which restricted the number of hours of work in a day, or number of days in a week, or allowed minimal facilities at the workplace.

An important point for our purposes here is that the British government was able to summon a large amount of public support, including the nationalist press, for the excesses committed on such communities. This is because the Criminal Tribes Act was posed widely as a social reform measure which reformed criminals through work. However, when they tried to make a living like everybody else, they did not find work outside the settlement because of public prejudice and ostracisation. This curious logic and anomalous situation has continued to this day.[19]

The cult of Thugs or Thuggee, known for murdering and robbing travellers in caravans, had apparently started around the 17th century and had reached significant proportions by the time the British established themselves in India. As the death toll rose, so did the myths and legend around them, so much so that they became part of British lexicon, and popular culture with novels like Confessions of a Thug (1839). When the British Raj decided to finally tackle them the 'Thuggee and Dacoity Department' was established, and civil servant William Sleeman first became superintendent of its operations in 1835, and later its commissioner in 1839, when the suppression of Thugs came into full force, supported by about 17 assistants and 100 employees, they captured around 3,000 thugs, out of which 466 were hanged, 1,564 transported and 933 imprisoned for life [20]. Eventually, the Thugs were all but extinct by 1850s. Such triumph over a tribe inspired the government to use the same know-how to tackle similar problems on a nationwide scale, employing theories evolved during the suppression of the thugs, which had in following decade gathered enough steam to feign authenticity, and public approval. Soon similar groups, which were deemed dangerous or as 'hereditary killers' were spotted and this eventually led to the formulation of 'Criminal Tribes Act' [12][21].

When the Bill was introduced in 1871 by jurist James Fitzjames Stephen, who also formulated the Indian Evidence Act 1872, stress was laid on various ethnological theories of caste which linked profession, upbringing and background, as he noted, "… people from time immemorial have been pursuing the caste system defined job-positions: weaving, carpentry and such were hereditary jobs. So there must have been hereditary criminals also who pursued their forefathers’ profession.". On another occasion defining his theory he had commented, "When we speak of professional criminals, we...(mean) a tribe whose ancestors were criminals from time immemorial, who are themselves destined by the usage of caste to commit crime, and whose descendants will be offenders against the law, until the whole tribe is exterminated or accounts for in manner of thugs" [6].

The tribes "notified" under the Act were labelled as Criminal Tribes for their so-called "criminal tendencies". As a result anyone born in these approximately 160 communities across the country was presumed as a "born criminal", irrespective of their criminal precedents. This gave the police sweeping powers to arrest them, control them, and monitor their movements. Once a tribe was officially notified, its members had no recourse to repeal such notices under the judicial system. From then on, their movements were monitored through a system of compulsory registration and passes, which specified where the holders could travel and reside, and district magistrates were required to maintain records of all such people [14].

An inquiry was set up in 1883, to investigate the need for extending the Act to the rest of India, and received an affirmative response. 1897 saw another amendment to the Act, wherein local governments were empowered to establish separate "reformatory" settlements, for tribal boys from age four to eighteen years, away from their parents.

Eventually, in 1911, it was enacted in Madras Presidency as well, bringing entire India into the jurisdiction of this law [22], in 1908, special ‘settlements’ were constructed for the notified tribes where they had to perform hard labour. With subsequent amendments to the Act, punitive penalties were increased, and fingerprinting of all members of the criminal tribe was made compulsory, such tight control according to many scholars was placed to ensure that no future revolts could take place [14].

Many of the tribes were "settled" in villages under the police guard, whose job was to ensure that no registered member of the tribe was absent with notice. Also imposition of punitive police posts on the villages with history of "misconduct" was also common [23].

In the coming decades, as a fallout of this act, a large section of the these notified tribes took up nomadic existence, living on the fringes of the society.

In 1936, Nehru denouncing the Act commented, "The monstrous provisions of the Criminal Tribes Act constitute a negation of civil liberty. No tribe [can] be classed as criminal as such and the whole principle [is] out of consonance with all civilised principles." [3][24].

Post-independence reforms

In January 1947, Government of Bombay set up a committee which included B.G. Kher, then Chief Minister Morarji Desai, and Gulzarilal Nanda to look into the matter of 'criminal tribes', this set into motion the final repeal of the Act in August 1949, which resulted in 2,300,000 tribals were being decriminalized [25]

Post independence, the Act was ultimately repealed, first in Madras Province in 1949 as the result of struggles led by Communist leaders such as P. Ramamurthi and P. Jeevanandam, and Forward Bloc leader U. Muthuramalingam Thevar, who had led many agitations in the villages starting 1929, urging the people to defy the CTA, as result the number of tribes under CTA was reduced. Other provincial governments soon followed suit.

Subsequently, the Committee appointed in the same year by the Central government, to study the utility of the existence of this law, reported in 1950 that the system violated the spirit of the Indian constitution. The Habitual Offenders Act (HOA) (1952) was enacted in the place of CTA, which states that an habitual offender is one who has been a victim of subjective and objective influences and has manifested a set practice in crime, and also presents a danger to society, though effectively re-stigmatized the already marginalized "criminal tribes". Since the stigma continues around the previously criminalized tribes, because of the ineffective nature of the new Act, which in effect meant relisting of the supposed Denotified tribes, and today the social category generally known as the denotified and nomadic tribes of India has a population of approximately 60 million in India.[26].

However many these denotified tribes continued to carry considerable social stigma of the Act and come under the purview of the 'Prevention of Anti-Social Activity Act' (PASA). Many of them have been denied the status of Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST) or Other Backward Classes (OBC), which would have allowed them avail Reservation under Indian law, which reserves seats for them in government jobs and educational institutions, thus most of them are still living below poverty line and sub-human condition [3]. Over the course of the century since its passing, the criminal identity attached to certain tribes by the Act, was internalized not just by the society, but also by the police, whose official methodology, even after repeal of the Act, often reflected the characteristics of manifestation of an era initiated by the Act, a century ago, where characteristic of crimes committed by certain tribes were closely watched, studied and documented [27].

National Human Rights Commission, in February, 2000 recommended repeal of the 'Habitual Offenders Act 1952' [13]. Later in March 2007, the UN’s anti-discrimination body Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), noted that “the so-called denotified and nomadic which are listed for their alleged ‘criminal tendencies’ under the former Criminal Tribes Act (1871), continue to be stigmatized under the Habitual Offenders Act (1952) (art. 2 (1)), and asked India to repeal the Habitual Offenders Act (1952) and effectively rehabilitate the denotified and nomadic tribes. According to the body, since much of 'Habitual Offenders Act (1952)' is derived from the earlier 'Criminal Tribes Act 1871', it doesn't show a marked departure in its intent, only gives the formed notified tribes a new name i.e. Denotified tribes, hence the stigma continues so does the oppression, as the law is being denounced on two counts, first that "all human beings are born free and equal", and second that it negates a valuable principle of the criminal justice system – innocent until proven guilty [28].

In 2008, the National Commission for Denotified, Nomadic and Semi-Nomadic Tribes (NCDNSNT) of Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment recommended that same reservations as available to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes be extended to around 11 crore people of denotified, nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes in India; the commission further recommended that the provisions of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 be applicable to these tribes as well [29]. Today, many governmental and non-governmental bodies are involved in the betterment of these denotified tribes through various schemes and educational programs [30].

Former notified tribes under the Act

Many of these tribes are present in both India and Pakistan.

Name Regions Badhak Rajasthan [31] Baghir Rajasthan [31] Baloch [32] Rajasthan Banjaras [13] Rajasthan, Punjab Baoris [33] Rajasthan, Punjab Baurias [23] Rajasthan, Punjab Bawarias [13] Rajasthan, Punjab Chhara Chharanagar, Gujarat Dhekaros Bhirbhum, West Bengal Dhikaru West Bengal Hurs [34] Pakistan Kanjar Rajasthan Korachas [35] Tamil Nadu Kurava [13] Tamil Nadu, Kerala Lambadis Andhra Pradesh Lodha West Bengal Mahtam [23] Rajasthan, Punjab Meenas [33] Rajasthan Nat Bihar Sabar West Bengal Sansi (nomadic) [23] Rajasthan, Punjab Phase Pardhi Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh Mukkulathor Tamilnadu Vaghari Gujarat Yerukala [35] Andhra Pradesh, Tamilnadu and Karnataka In films

So far two shorts films have made on the situation of denotified tribes in India, first "Mahasweta Devi: Witness, Advocate, Writer" (2001) by Shashwati Talukdar, a film on the life and works of social activist and Magsaysay Award winner, Mahasweta Devi, who has been working for tribes for over three decades. Second, "Acting Like a Thief" (2005) by P. Kerim Friedman & Shashwati Talukdar, about a Chhara tribal theatre group in Ahmedabad, India.[36]. The 2007 National Film Award-winning Tamil feature film, "Paruthi Veeran" also documents the scenarios and mindsets left behind by the Act in rural Tamilnadu [37].

See also

Further reading

- Britain in India, 1765–1905, Volume 1: Justice, Police, Law and Order, Editors: John Marriott and Bhaskar Mukhopadhyay, Advisory Editor: Partha Chatterjee. Published by Pickering and Chatto Publishers, 2006. Full text of Criminal Tribes’ Act, 1871, Act XXVII (1871) p.227-239

- The History of railway thieves: With illustrations & hints on detection (The criminal tribes of India series), by M. Pauparao Naidu. Higginbothams. 4th edition. 1915.

- Dishonoured by History: Criminal Tribes and British Colonial Policy, by Meena Radhakrishna. Published by Sangam Books Ltd, 2001. ISBN 978-8125020905.

- The land pirates of India;: An account of the Kuravers, a remarkable tribe of hereditary criminals, their extraordinary skill as thieves, cattle-lifters & highwayman & c, and their manners & customs, by William John Hatch. Pub. J.B. Lippincott Co. 1928. ASIN B000855LQK.

- The Criminal Tribes: A Socio-economic Study of the Principal Criminal Tribes and Castes in Northern India, by Bhawani Shanker Bhargava. Published by Published for the Ethnographic and Folk Culture Society, United Provinces, by the Universal Publishers, 1949.

- The Ex-criminal Tribes of India, by Y. C. Simhadri. Published by National, 1979.

- Crime and criminality in British India, by Anand A. Yang. Published for the Association for Asian Studies by the University of Arizona Press, 1985. ISBN 0816509514.

- Creating Born Criminals, by Nicole Rafter. University of Illinois Press. 1998. ISBN 025206741X.

- Branded by Law: Looking at India's Denotified Tribes, by Dilip D'Souza. Published by Penguin Books, 2001. ISBN 0141007494.

- The Strangled Traveler: Colonial Imaginings and the Thugs of India, by Martine van Woerkens, tr. by Catherine Tihanyi. University Of Chicago Press. 2002. ISBN 0226850854.

- Legible Bodies: Race, Criminality and Colonialism in South Asia, by Clare Anderson. Berg Publishers. 2004. ISBN 1859738605.

- The Criminal Tribes in India, by S.T. Hollins. Published by Nidhi Book Enclave. 2005. ISBN 8190208667.

- Articles of Criminal Tribes

- Notes On Criminal Tribes Residing In Or Frequenting The Bombay Presidency, Berar, And The Central Provinces (1882), by E. J. Gunthorpe. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. 2008. ISBN 1436621887.

References

- ^ Archives CID Govt. of West Bengal.

- ^ Awadh, United Province, Punjab, North-West Frontier Province

- ^ a b c Suspects forever: Members of the "denotified tribes" continue to bear the brunt of police brutality Frontline, The Hindu, Volume 19 - Issue 12, June 8–21, 2002.

- ^ Readings - Criminal Tribes Act (XXVII of 1871) Columbia University.

- ^ Bate, Crispin (1995) (PDF). Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: The Early Origins of Indian Anthropometry. Edinburgh: Centre for South Asian Studies, School of Social & Political Studies, University of Edinburgh. ISBN 1-900-795-02-7. http://www.csas.ed.ac.uk/fichiers/BATES_RaceCaste&Tribe.pdf.

- ^ a b Raj and Born Criminals Crime, gender, and sexuality in criminal prosecutions, by Louis A. Knafla. Published by Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. ISBN 0313310130. Page 124.

- ^ a b Year of Birth - 1871: Mahasweta Devi on India's Denotified Tribes by Mahasweta Devi. indiatogether.org.

- ^ a b Denotified and Nomadic Tribes in Maharashtra by Motiraj Rathod Harvard University.

- ^ Colonial Act still haunts denotified tribes: expert The Hindu, Mar 27, 2008.

- ^ Injustice, go away: Phase Pardhis are one of India's denotified tribes but the authorities and society in general continue to think of them as criminals The Hindu, Sunday, Jun 01, 2003.

- ^ Kannabirān, Kalpana; Ranbir Singh (2008). Challenging the Rules of Law: Colonialism, Criminology and Human Rights in India. SAGE Publications Inc. p. 22. ISBN 0761936653. http://books.google.com/books?id=EaMGo6zqzNYC&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=criminal+tribes+act+1851&source=bl&ots=PTrzoceu-T&sig=kiD08u8wNI41fyIZA7btGlr_Qgs&hl=en&ei=wJ3SSqjJMYeuswO4_LnwCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CC4Q6AEwCTgK#v=onepage&q=criminal%20tribes%20act%201851&f=false.

- ^ a b Imperial Deceivers: Myths of the oriental criminal and the origin of the word 'thug' by Kevin Rushby, The Guardian, January 18, 2003.

- ^ a b c d e Meena Radhakrishna (2006-07-16). "Dishonoured by history". folio: Special issue with the Sunday Magazine. The Hindu. http://www.hinduonnet.com/folio/fo0007/00070240.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ a b c The Criminal Tribe Act (Act XXVII of 1871) Muslims and Crime: A Comparative Study, by Muzammil Quraishi. Published by Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005. ISBN 075464233X. Page 51.

- ^ Native Prints Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification, by Simon A. Cole. Published by Harvard University Press, 2002. ISBN 0674010027. Page 67-68.

- ^ English Social reformer, Mary Carpenter (1807-1877) was first to coin the term "dangerous classes".

- ^ a b Colonialism and Criminal Castes With Respect to Sex: Negotiating Hijra Identity in South India, by Gayatri Reddy. Published by University of Chicago Press, 2005. ISBN 0226707563. Page 26-27

- ^ Professional criminals Customary strangers: new perspectives on peripatetic peoples in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, by Joseph C. Berland, Aparna Rao. Published by Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004. ISBN 0897897714. Page 11.

- ^ Dishonoured by History Dr. Meena Radhakrishna http://www.hinduonnet.com/folio/fo0007/00070240.htm

- ^ In Bandit Land Indian Express, Jul 27, 2003.

- ^ Sinister sects: Thug, Mike Dash's investigation into the gangs who preyed on travellers in 19th-century India by Kevin Rushby, The Guardian, Saturday, June 11, 2005.

- ^ Ethnographers Civilising Natures: Race, Resources and Modernity in Colonial South India, by Kavita Philip. Published by Orient Blackswan, 2004. ISBN 8125025863. Page 174.

- ^ a b c d Punjab - Police and Jails The Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 20, p. 363.

- ^ Bania Arrested for Spying by Dilip D'Souza. Rediff.com, January 18, 2003.

- ^ The Indian Constitution--: A Case Study of Backward Classes, by Ratna G. Revankar. Published by Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1971. ISBN 0838676707. Page 238.

- ^ C.R. Bijoy (February 2003). "The Adivasis of India - A History of Discrimination, Conflict, and Resistance". PUCL Bulletin. People's Union for Civil Liberties. http://www.pucl.org/Topics/Dalit-tribal/2003/adivasi.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ Colonizing and Transforming the Criminal Tribesman Deviant Bodies: Critical Perspectives on Difference in Science and Popular Culture, by Jennifer Terry, Jacqueline Urla. Published by Indiana University Press, 1995. ISBN 0253209757. Page 100.

- ^ Repeal the Habitual Offenders Act and affectively rehabilitate the denotified tribes, UN to India Asian Tribune, Mon, March 19, 2007.

- ^ Panel favours reservation for nomadic tribes by Raghvendra Rao, Indian Express, Aug 21, 2008.

- ^ Who are the Chharas? - Rehabilitation of Chharas, a De-Notified Tribe Jan 26, 2006.

- ^ a b Central India - Police and Jails The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1908, v. 9, p. 384.

- ^ Karnal District - Administration The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1908, v. 15, p. 57.

- ^ a b Jaipur - Administration The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1908, v. 13, p. 397.

- ^ Thar and Parkar - Administration The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1908, v. 23, p. 314.

- ^ a b Dishonoured by History: "criminal Tribes" and British Colonial Policy, by Meena Radhakrishna. Published by Orient Blackswan, 2001. ISBN 812502090X. Page 2

- ^ Mahasweta Devi: Witness, Advocate, Writer Documentary Educational Resources (DER).

- ^ Paruthi Veeran - Ameer’s Passion continues….

- Meena Radhakrishna. Dishonoured by History: "criminal Tribes" and British Colonial Policy. Orient Blackswan, 2001. ISBN 9788125020905. [1]

External links

Categories:- 1871 in law

- British rule in India

- Legal history of Pakistan

- Discrimination law

- Legal history of India

- Social history of India

- Human rights in India

- Indian caste legislation

- Repealed Indian legislation

- Legislation in British India

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.