- Morinda citrifolia

-

"Noni" redirects here. For other uses, see Noni (disambiguation).

Morinda citrifolia

Leaves and fruit Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae (unranked): Angiosperms (unranked): Eudicots (unranked): Asterids Order: Gentianales Family: Rubiaceae Genus: Morinda Species: M. citrifolia Binomial name Morinda citrifolia

L.Morinda citrifolia, commonly known as great morinda, Indian mulberry, nunaakai (Tamil Nadu, India) , dog dumpling (Barbados), mengkudu (Indonesia and Malaysia), Kumudu (Balinese), pace (Javanese), beach mulberry, cheese fruit[1] or noni (from Hawaiian) is a tree in the coffee family, Rubiaceae. Morinda citrifolia's native range extends through Southeast Asia and Australasia, and the species is now cultivated throughout the tropics and widely naturalised.[2]

Contents

Growing habitats

M. citrifolia grows in shady forests as well as on open rocky or sandy shores. It reaches maturity in about 18 months and then yields between 4–8 kilograms (8.8–18 lb) of fruit every month throughout the year. It is tolerant of saline soils, drought conditions, and secondary soils. It is therefore found in a wide variety of habitats: volcanic terrains, lava-strewn coasts, and clearings or limestone outcrops. It can grow up to 9 metres (30 ft) tall, and has large, simple, dark green, shiny and deeply veined leaves.

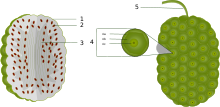

The plant bears flowers and fruits all year round. The fruit is a multiple fruit that has a pungent odour when ripening, and is hence also known as cheese fruit or even vomit fruit. It is oval in shape and reaches 4–7 centimetres (1.6–2.8 in) size. At first green, the fruit turns yellow then almost white as it ripens. It contains many seeds. It is sometimes called starvation fruit. Despite its strong smell and bitter taste, the fruit is nevertheless eaten as a famine food[3] and, in some Pacific islands, even a staple food, either raw or cooked.[4] Southeast Asians and Australian Aborigines consume the fruit raw with salt[5] or cook it with curry. The seeds are edible when roasted.

M. citrifolia is especially attractive to weaver ants, which make nests out of the leaves of the tree. These ants protect the plant from some plant-parasitic insects. The smell of the fruit also attracts fruit bats, which aid in dispersing the seeds.

Nutrients and phytochemicals

M. citrifolia fruit in Honolulu

M. citrifolia fruit in Honolulu

M. citrifolia fruit powder contains carbohydrates and dietary fibre in moderate amounts.[6] These macronutrients evidently reside in the fruit pulp, as M. citrifolia juice has sparse nutrient content.[7] The main micronutrients of M. citrifolia pulp powder include vitamin C, niacin (vitamin B3), iron and potassium.[6] Vitamin A, calcium and sodium are present in moderate amounts. When M. citrifolia juice alone is analyzed and compared to pulp powder, only vitamin C is retained[7] in an amount that is about half the content of a raw navel orange.[8] Sodium levels in M. citrifolia juice (about 3% of Dietary Reference Intake, DRI)[6] are high compared to an orange, and potassium content is moderate. M. citrifolia juice is otherwise similar in micronutrient content to a raw orange.[8]

M. citrifolia fruit contains a number of phytochemicals, including lignans, oligo- and polysaccharides, flavonoids, iridoids, fatty acids, scopoletin, catechin, beta-sitosterol, damnacanthal, and alkaloids. Although these substances have been studied for bioactivity, current research is insufficient to conclude anything about their effects on human health.[9][10][11][12][13] These phytochemicals are not unique to M. citrifolia, as they exist in various plants.

Traditional medicine

The green fruit, leaves, and root/rhizome were traditionally used in Polynesian cultures to treat menstrual cramps, bowel irregularities, diabetes, liver diseases, and urinary tract infections.[14]

Consumer applications

The bark of the great morinda produces a brownish-purplish dye for batik making. In Hawaii, yellowish dye is extracted from its roots to dye cloth.[15]

There have been recent applications for the use of M. citrifolia seed oil[16] which contains linoleic acid possibly useful when applied topically to skin, e.g., anti-inflammation, acne reduction, moisture retention.[17][18][19]

See also

- Tahitian Noni International – A multi-level marketing company selling sweetened Noni juice, based in Provo, Utah.

- Noni juice

References

- ^ Plants by Common Name – James Cook University

- ^ Nelson, SC (2006-04-01). "Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry: Morinda citrifolia (noni)". http://traditionaltree.org.

- ^ Krauss, BH (1993). Plants in Hawaiian Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.[page needed]

- ^ Morton, Julia F. (1992). "The ocean-going noni, or Indian Mulberry (Morinda citrifolia, Rubiaceae) and some of its "colorful" relatives". Economic Botany 46 (3): 241–56. doi:10.1007/BF02866623.

- ^ Cribb, A.B. & Cribb, J.W. (1975) Wild Food in Australia. Sydney: Collins.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Nelson, Scot C. (2006) "Nutritional Analysis of Hawaiian Noni (Noni Fruit Powder)" The Noni Website. Retrieved 15-06-2009.

- ^ a b Nelson, Scot C. (2006) "Nutritional Analysis of Hawaiian Noni (Pure Noni Fruit Juice)" The Noni Website. Retrieved 15-06-2009.

- ^ a b World's Healthiest Foods, in-depth nutrient analysis of a raw orange

- ^ Saleem, Muhammad; Kim, Hyoung Ja; Ali, Muhammad Shaiq; Lee, Yong Sup (2005). "An update on bioactive plant lignans". Natural Product Reports 22 (6): 696. doi:10.1039/b514045p. PMID 16311631.

- ^ Deng, Shixin; Palu, ‘Afa K.; West, Brett J.; Su, Chen X.; Zhou, Bing-Nan; Jensen, Jarakae C. (2007). "Lipoxygenase Inhibitory Constituents of the Fruits of Noni (Morindacitrifolia) Collected in Tahiti". Journal of Natural Products 70 (5): 859–62. doi:10.1021/np0605539. PMID 17378609.

- ^ Lin, Chwan Fwu; Ni, Ching Li; Huang, Yu Ling; Sheu, Shuenn Jyi; Chen, Chien Chih (2007). "Lignans and anthraquinones from the fruits ofMorinda citrifolia". Natural Product Research 21 (13): 1199–204. doi:10.1080/14786410601132451. PMID 17987501.

- ^ Levand, Oscar; Larson, Harold (2009). "Some Chemical Constituents of Morinda citrifolia". Planta Medica 36 (06): 186–7. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1097264.

- ^ Mohd Zin, Z.; Abdul Hamid, A.; Osman, A.; Saari, N.; Misran, A. (2007). "Isolation and Identification of Antioxidative Compound from Fruit of Mengkudu (Morinda citrifoliaL.)". International Journal of Food Properties 10 (2): 363–73. doi:10.1080/10942910601052723.

- ^ Wang MY, West BJ, Jensen CJ, Nowicki D, Su C, Palu AK, Anderson G (2002). "Morinda citrifolia (Noni): a literature review and recent advances in Noni research". Pharmacol Sin 23 (12): 1127-41. PMID 12466051.

- ^ Thompson, RH (1971). Naturally Occurring Anthraquinones. New York: Academic Press.[page needed]

- ^ West, Brett J.; Jarakae Jensen, Claude; Westendorf, Johannes (2008). "A new vegetable oil from noni (Morinda citrifolia) seeds". International Journal of Food Science & Technology 43 (11): 1988–92. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2008.01802.x.

- ^ "Plant oils: Topical application and anti-inflammatory effects (croton oil test)". Dermatol. Monatsschr 179: 173. 1993.

- ^ Letawe, C; Boone, M; Pierard, GE (1998). "Digital image analysis of the effect of topically applied linoleic acid on acne microcomedones". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 23 (2): 56–8. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.1998.00315.x. PMID 9692305.

- ^ Darmstadt, GL; Mao-Qiang, M; Chi, E; Saha, SK; Ziboh, VA; Black, RE; Santosham, M; Elias, PM (2007). "Impact of topical oils on the skin barrier: possible implications for neonatal health in developing countries". Acta Paediatrica 91 (5): 546–54. doi:10.1080/080352502753711678. PMID 12113324.

Further reading

- Noni: The Complete Guide for Consumers and Growers. Permanent Agriculture Resources. August 2006. pp. 112. ISBN 0-9702544-6-6.

- Kamiya, Kohei; Tanaka, Yohei; Endang, Hanani; Umar, Mansur; Satake, Toshiko (2004). "Chemical Constituents of Morinda citrifolia Fruits Inhibit Copper-Induced Low-Density Lipoprotein Oxidation". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 52 (19): 5843–8. doi:10.1021/jf040114k. PMID 15366830.

External links

- "The Noni Website". 2006. http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/noni/.

- Thomas, Chris (August 30, 2002). "Noni No Miracle Cure". Cancerpage.com. http://www.cancerpage.com/news/article.asp?id=4799.

- Anthony, Mark. "Noni or NIMBY?". Foodprocessing.com. http://www.foodprocessing.com/articles/2007/018.html.

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.