- Marble sculpture

-

Lorenzo Bartolini, (Italian, 1777–1850), La Table aux Amours (The Demidoff Table), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, Marble sculpture

Marble sculpture is the art of creating three-dimensional forms from marble. Sculpture is among the oldest of the arts. Even before painting cave walls, early humans fashioned shapes from stone. From these beginnings, artifacts have evolved to their current complexity. The point at which they became art is for the beholder to decide.

Contents

Material origin and qualities

Marble is a metamorphic rock derived from limestone, composed mostly of calcite (a crystalline form of calcium carbonate, CaCO3). The original source of the parent limestone is the seabed deposition calcium carbonate in the form of microscopic animal skeletons or similar materials. Marble is formed when the limestone is transformed by heat and pressure after being overlain by other materials. The finest marbles for sculpture have no or few stains (some natural stain can be seen in the sculpture shown at left, which the sculptor has skillfully incorporated into the sculpture).

Advantages

Among the commonly available stones only marble has a slight surface translucency that is comparable to that of human skin. It is this translucency that gives a marble sculpture a visual depth beyond its surface and this evokes a certain realism when used for figurative works. Marble also has the advantage that when first quarried it is relatively soft and easy to work, refine, and polish.[1] As the finished marble ages it becomes harder and more durable. Preference to the cheaper and less translucent limestone is based largely on the fineness of marble's grain, which enables the sculptor to render minute detail in a manner not always possible with limestone; it is also more weather resistant.

Disadvantages

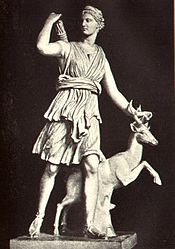

Marble does not bear handling well as it will absorb skin oils when touched, which leads to yellow brownish staining. While more resistant than limestone it is subject to attack by weak acids, and so performs poorly in outdoor environments subject to acid rain. For severe environments, granite is a more lasting material but one which is far more difficult to work and much less suitable for refined works.[2] Compared to metals such as bronze, marble lacks ductility and strength, requiring special structural considerations when planning a sculpture. In the sculpture shown to the right, the figure can be placed upon slender lower legs and the balls of the feet only because the bending stress in the sculpture is taken through the flowing drapery of the skirt, which is founded upon an upthrust portion of the ground and with the feet forms a tripod-like foundation for the mass. For comparison see some of the examples in the article concerning bronze sculpture (especially the sculpture Jeté) for the ease with which action and extension may be expressed.

Developing a sculpture

The work begins with the selection of a stone for carving. The artist may carve in the direct way, by carving without a model. Or the sculptor may begin with a clearly defined model to be copied in stone. Frequently the sculptor would begin by forming a model in clay or wax, and then copying this in stone by measuring with calipers or a pointing machine. Some artists use the stone itself as inspiration; the Renaissance artist Michelangelo claimed that his job was to free the human form trapped inside the block.

When he or she is ready to carve, the carver usually begins by knocking off, or "pitching", large portions of unwanted stone. For this task he may select a point chisel, which is a long, hefty piece of steel with a point at one end and a broad striking surface at the other. A pitching tool may also be used at this early stage; which is a wedge-shaped chisel with a broad, flat edge. The pitching tool is useful for splitting the stone and removing large, unwanted chunks. The sculptor also selects a mallet, which is often a hammer with a broad, barrel-shaped head.

The carver places the point of the chisel or the edge of the pitching tool against a selected part of the stone, then swings the mallet at it with a controlled stroke. He must be careful to strike the end of the tool accurately; the smallest miscalculation can damage the stone, not to mention the sculptor’s hand. When the mallet connects to the tool, energy is transferred along the tool, shattering the stone. Most sculptors work rhythmically, turning the tool with each blow so that the stone is removed quickly and evenly. This is the “roughing out” stage of the sculpting process.

Once the general shape of the statue has been determined, the sculptor uses other tools to refine the figure. A toothed chisel or claw chisel has multiple gouging surfaces which create parallel lines in the stone. These tools are generally used to add texture to the figure. An artist might mark out specific lines by using calipers to measure an area of stone to be addressed, and marking the removal area with pencil, charcoal or chalk. The stone carver generally uses a shallower stroke at this point in the process.

Eventually the sculptor has changed the stone from a rough block into the general shape of the finished statue. Tools called rasps and rifflers are then used to enhance the shape into its final form. A rasp is a flat, steel tool with a coarse surface. The sculptor uses broad, sweeping strokes to remove excess stone as small chips or dust. A riffler is a smaller variation of the rasp, which can be used to create details such as folds of clothing or locks of hair.

The final stage of the carving process is polishing. Sandpaper can be used as a first step in the polishing process, or sand cloth. Emery, a stone that is harder and rougher than the sculpture media, is also used in the finishing process. This abrading, or wearing away, brings out the color of the stone, reveals patterns in the surface and adds a sheen. Tin and iron oxides are often used to give the stone a highly reflective exterior.

Tools

The Italian terms for the basic carving tools of stone sculpture are given here, and where possible the English terms have been included.

- La Mazza - The mallet. This is used to strike the chisel.

- Gli Scalpelli - The chisels. These come in various types:

- La Subbia - (the Point) a pointed chisel or punch

- L'Unghietto - (Round or Rondel Chisel) Literally, "little fingernail"

- La Gradina - (Toothed Chisel or Claw) a chisel with multiple teeth-

- Lo Scalpello - a flat chisel

- Lo Scapezzatore - (Pitcher or Pitching Tool) a hefty chisel with a broad blunt edge, for splitting.

- Il Martello Pneumatico - Pneumatic hammer

- Il Flessibile - an angle grinder, fitted with an electrolysis-applied diamond studded blade

- Hand Drill

In addition to those hand tools listed above, the marble sculptor would use a variety of hammers - both for the striking of edge tools (chisels and hand drills) and for striking the stone directly (Bocciarda a Martello in Italian, Boucharde in French, Bush Hammer in English). Following the work of the hammer and chisel, the sculptor will sometimes refine the form further through the use of Rasps, Files and Abrasive Rubbing Stones and/or Sandpaper to smooth the surface contours of the form. To achieve a high-lustre polish on marble a very fine abrasive, tin oxide, is used following the use of pumice or finer grits of sandpaper.

Tool technique

Hammer and point work is the technique used in working stone, in use at least since Roman times, as it is described in the legend of Pygmalion, and even earlier, the ancient Greek sculptors used it from c. 650 BC. It consists of holding the pointed chisel against the stone and swinging the hammer at it as hard as possible. When the hammer connects with the striking end of the chisel, its energy is transferred down the length and concentrates on a single point on the surface of the block, breaking the stone. This is continued in a line following the desired contour. It may sound simple but many months are required to attain competency. A good stone worker can maintain a rhythm of relatively longer blows (about one per second), swinging the hammer in a wider arc, lifting the chisel between blows to flick out any chips that remain in the way, and repositioning it for the next blow. This way, one can drive the point deeper into the stone and remove more material at a time. Some stoneworkers also spin the subbia in their fingers between hammer blows, thus applying with each blow a different part of the point to the stone. This helps prevent the point from breaking.

See also

A few well known marble sculptures

- Elgin Marbles, in the British Museum, London

- Aphrodite of Milos, (Venus de Milo) in the Louvre, Paris

- David by Michelangelo, in Florence

- Laocoön and his Sons by Agesander, in the Vatican Museums, Vatican City

- Moses by Michelangelo, in Rome

- Pietà by Michelangelo, in the Vatican

- Discobolus Lancellotti, the Lancellotti discus thrower in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome

References

External links

Categories:- Sculptures by medium

- Carving

- Sculpture techniques

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.