- HMAC

-

In cryptography, HMAC (Hash-based Message Authentication Code) is a specific construction for calculating a message authentication code (MAC) involving a cryptographic hash function in combination with a secret key. As with any MAC, it may be used to simultaneously verify both the data integrity and the authenticity of a message. Any cryptographic hash function, such as MD5 or SHA-1, may be used in the calculation of an HMAC; the resulting MAC algorithm is termed HMAC-MD5 or HMAC-SHA1 accordingly. The cryptographic strength of the HMAC depends upon the cryptographic strength of the underlying hash function, the size of its hash output length in bits, and on the size and quality of the cryptographic key.

An iterative hash function breaks up a message into blocks of a fixed size and iterates over them with a compression function. For example, MD5 and SHA-1 operate on 512-bit blocks. The size of the output of HMAC is the same as that of the underlying hash function (128 or 160 bits in the case of MD5 or SHA-1, respectively), although it can be truncated if desired.

The definition and analysis of the HMAC construction was first published in 1996 by Mihir Bellare, Ran Canetti, and Hugo Krawczyk,[1] who also wrote RFC 2104. This paper also defined a variant called NMAC that is rarely if ever used. FIPS PUB 198 generalizes and standardizes the use of HMACs. HMAC-SHA-1 and HMAC-MD5 are used within the IPsec and TLS protocols.

Contents

Definition (from RFC 2104)

Let:

- H(·) be a cryptographic hash function

- K be a secret key padded to the right with extra zeros to the input block size of the hash function, or the hash of the original key if it's longer than that block size

- m be the message to be authenticated

- ∥ denote concatenation

- ⊕ denote exclusive or (XOR)

- opad be the outer padding (0x5c5c5c…5c5c, one-block-long hexadecimal constant)

- ipad be the inner padding (0x363636…3636, one-block-long hexadecimal constant)

Then HMAC(K,m) is mathematically defined by

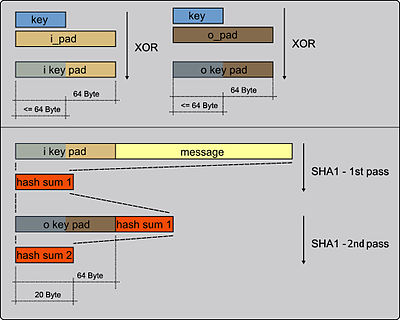

- HMAC(K,m) = H((K ⊕ opad) ∥ H((K ⊕ ipad) ∥ m)).

Implementation

The following pseudocode demonstrates how HMAC may be implemented. Blocksize is 64 (bytes) when using one of the following hash functions: SHA-1, MD5, RIPEMD-128/160.[2]

function hmac (key, message) if (length(key) > blocksize) then key = hash(key) // keys longer than blocksize are shortened end if if (length(key) < blocksize) then key = key ∥ [0x00 * (blocksize - length(key))] // keys shorter than blocksize are zero-padded ('∥' is concatenation) end if o_key_pad = [0x5c * blocksize] ⊕ key // Where blocksize is that of the underlying hash function i_key_pad = [0x36 * blocksize] ⊕ key // Where ⊕ is exclusive or (XOR) return hash(o_key_pad ∥ hash(i_key_pad ∥ message)) // Where '∥' is concatenation end function

Example usage

A business that suffers from attackers that place fraudulent Internet orders may insist that all its customers deposit a secret key with them. Along with an order, a customer must supply the order's HMAC digest, computed using the customer's symmetric key. The business, knowing the customer's symmetric key, can then verify that the order originated from the stated customer and has not been tampered with.

Design principles

The design of the HMAC specification was motivated by the existence of attacks on more trivial mechanisms for combining a key with a hash function. For example, one might assume the same security that HMAC provides could be achieved with MAC = H(key ∥ message). However, this method suffers from a serious flaw: with most hash functions, it is easy to append data to the message without knowing the key and obtain another valid MAC. The alternative, appending the key using MAC = H(message ∥ key), suffers from the problem that an attacker who can find a collision in the (unkeyed) hash function has a collision in the MAC. Using MAC = H(key ∥ message ∥ key) is better, however various security papers have suggested vulnerabilities with this approach, even when two different keys are used.[1][3][4]

No known extensions attacks have been found against the current HMAC specification which is defined as H(key1 ∥ H(key2 ∥ message)) because the outer application of the hash function masks the intermediate result of the internal hash. The values of ipad and opad are not critical to the security of the algorithm, but were defined in such a way to have a large Hamming distance from each other and so the inner and outer keys will have fewer bits in common.

Security

The cryptographic strength of the HMAC depends upon the size of the secret key that is used. The most common attack against HMACs is brute force to uncover the secret key. HMACs are substantially less affected by collisions than their underlying hashing algorithms alone.[5] [6] .[7] Therefore, HMAC-MD5 does not suffer from the same weaknesses that have been found in MD5.

In 2006, Jongsung Kim, Alex Biryukov, Bart Preneel, and Seokhie Hong showed how to distinguish HMAC with reduced versions of MD5 and SHA-1 or full versions of HAVAL, MD4, and SHA-0 from a random function or HMAC with a random function. Differential distinguishers allow an attacker to devise a forgery attack on HMAC. Furthermore, differential and rectangle distinguishers can lead to second-preimage attacks. HMAC with the full version of MD4 can be forged with this knowledge. These attacks do not contradict the security proof of HMAC, but provide insight into HMAC based on existing cryptographic hash functions. [8]

Examples of HMAC (MD5, SHA1, SHA256 )

Here are some empty HMAC values -

HMAC_MD5("", "") = 0x 74e6f7298a9c2d168935f58c001bad88 HMAC_SHA1("", "") = 0x fbdb1d1b18aa6c08324b7d64b71fb76370690e1d HMAC_SHA256("", "") = 0x b613679a0814d9ec772f95d778c35fc5ff1697c493715653c6c712144292c5ad

Here are some non-empty HMAC values -

HMAC_MD5("key", "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog") = 0x 80070713463e7749b90c2dc24911e275 HMAC_SHA1("key", "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog") = 0x de7c9b85b8b78aa6bc8a7a36f70a90701c9db4d9 HMAC_SHA256("key", "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog") = 0x f7bc83f430538424b13298e6aa6fb143ef4d59a14946175997479dbc2d1a3cd8

External links

- FIPS PUB 198, The Keyed-Hash Message Authentication Code

- PHP HMAC implementation

- Python HMAC implementation

- Perl HMAC implementation

- Ruby HMAC implementation

- C HMAC implementation

- Java implementation

- JavaScript HMAC implementation

- Lightweight JavaScript implementation (SHA-256 & HMAC SHA-256)

- .NET's System.Security.Cryptography.HMAC

References

- ^ a b Bellare, Mihir; Canetti, Ran; Krawczyk, Hugo (1996). "Keying Hash Functions for Message Authentication". http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.134.8430.

- ^ RFC 2104, section 2, "Definition of HMAC", page 3.

- ^ Preneel, Bart; van Oorschot, Paul C. (1995). "MDx-MAC and Building Fast MACs from Hash Functions". http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.34.3855. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ^ Preneel, Bart; van Oorschot, Paul C. (1995). "On the Security of Two MAC Algorithms". http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.42.8908. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ^ Bruce Schneier (August 2005). "SHA-1 Broken". http://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2005/02/sha1_broken.html. Retrieved 2009-01-09. "although it doesn't affect applications such as HMAC where collisions aren't important"

- ^ IETF (February 1997). "RFC 2104". http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2104.txt. Retrieved 2009-12-03. "The strongest attack known against HMAC is based on the frequency of collisions for the hash function H ("birthday attack") [PV,BCK2], and is totally impractical for minimally reasonable hash functions."

- ^ Bellare, Mihir (June 2006). "New Proofs for NMAC and HMAC: Security without Collision-Resistance". In Dwork, Cynthia. Advances in Cryptology – Crypto 2006 Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4117. Springer-Verlag. http://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~mihir/papers/hmac-new.html. Retrieved 2010-05-25. "This paper proves that HMAC is a PRF under the sole assumption that the compression function is a PRF. This recovers a proof based guarantee since no known attacks compromise the pseudorandomness of the compression function, and it also helps explain the resistance-to-attack that HMAC has shown even when implemented with hash functions whose (weak) collision resistance is compromised."

- ^ Jongsung, Kim; Biryukov, Alex; Preneel, Bart; Hong, Seokhie (2006). On the Security of HMAC and NMAC Based on HAVAL, MD4, MD5, SHA-0 and SHA-1. http://eprint.iacr.org/2006/187.pdf.

- Notes

- Mihir Bellare, Ran Canetti and Hugo Krawczyk, Keying Hash Functions for Message Authentication, CRYPTO 1996, pp1–15 (PS or PDF).

- Mihir Bellare, Ran Canetti and Hugo Krawczyk, Message authentication using hash functions: The HMAC construction, CryptoBytes 2(1), Spring 1996 (PS or PDF).

Cryptographic hash functions and message authentication codes (MACs) Common functions Functions SHA-3 finalists BLAKE · Grøstl · JH · Keccak · SkeinMAC algorithms Authenticated

encryption modesAttacks Misc. Standardization Cryptography Categories:- Message authentication codes

- Hashing

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.