- Jeffrey Dahmer

-

Jeffrey Dahmer

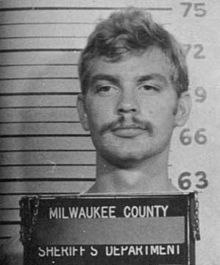

Dahmer's mugshot taken by the Milwaukee County Sheriff's DepartmentBackground information Birth name Jeffrey Lionel Dahmer Also known as The Milwaukee Cannibal,

The Milwaukee MonsterBorn May 21, 1960

West Allis, Wisconsin, U.S.Died November 28, 1994 (aged 34)

Portage, Wisconsin, U.S.Cause of death Severe head trauma Conviction Child molestation,

Disorderly conduct,

Indecent exposure,

Murder,

Public intoxicationSentence Life imprisonment (15 life terms) Killings Number of victims: 17 Span of killings June 6, 1978–July 19, 1991 Country United States State(s) Ohio, Wisconsin Date apprehended July 22, 1991 Jeffrey Lionel Dahmer (May 21, 1960 – November 28, 1994) was an American serial killer and sex offender. Dahmer murdered 17 men and boys between 1978 and 1991, with the majority of the murders occurring between 1987 and 1991. His murders involved rape, dismemberment, necrophilia and cannibalism. On November 28, 1994, he was beaten to death by an inmate at the Columbia Correctional Institution, where he had been incarcerated.

Contents

Early life

Dahmer was born in West Allis, Wisconsin, the son of Joyce Annette (née Flint) and Lionel Herbert Dahmer, an analytical chemist.[1] Seven years later, his brother David was born.[2] Joyce Dahmer reportedly had a difficult pregnancy with her elder son. When he was eight years old, he moved with his family to Bath, Ohio. Dahmer's early childhood was by all accounts normal, but he grew increasingly withdrawn and uncommunicative between the ages of 10 and 15, showing little interest in any hobbies or social interactions.[3] He biked around his neighborhood looking for dead animals, which he dissected at home (or in the woods near his home.) In one instance, he went so far as to put a dog's head on a stake.[4] Dahmer began drinking in his teens and was an alcoholic by the time of his high school graduation.[5]

In 1977, Lionel and Joyce Dahmer divorced.[6] Dahmer attended The Ohio State University, but dropped out after one quarter, having failed to attend most of his classes.[7] He was drunk for the majority of the term.[8] Dahmer's father then forced him to enlist in the Army.[9] Dahmer did well at first,[10] but he was discharged after two years because of his alcoholism.[11] When the Army discharged Dahmer in 1981, he was provided with a plane ticket to anywhere in the country. Dahmer later told police he could not go home to face his father, so he headed to Miami Beach, Florida, because he was "tired of the cold".[12] He spent most of his time there at a hospital, but was soon kicked out for drinking.[12] After coming home, he continued to drink heavily, and he was arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct later in 1981.[13]

In 1982, Dahmer moved in with his grandmother in West Allis,[14] where he lived for six years.[15] During this time, his behavior grew increasingly strange. His grandmother once found a fully dressed male mannequin in his closet; Dahmer had stolen it from a store.[16] On another occasion, she found a .357 Magnum under his bed.[17] Terrible smells came from the basement; Dahmer told his father that he had brought home a dead squirrel and dissolved it with chemicals.[18] He was arrested twice for indecent exposure, in 1982 and 1986;[19] in his second offense, he masturbated in front of two boys.[20]

In summer 1988, Dahmer's grandmother asked him to move out because of his late nights, his strange behavior, and the foul smells from the basement. He then found an apartment on Milwaukee's West side, closer to his job at the Ambrosia Chocolate Factory.[21] On September 26, 1988, one day after moving into his apartment, he was arrested for drugging and sexually fondling a 13-year-old boy in Milwaukee named Somsack Sinthasomphone.[22] He was sentenced to five years probation and one year in a work release camp. He was required to register as a sex offender.[23] Dahmer was paroled from the work release camp two months early, and he soon moved into a new apartment.[24] Shortly thereafter, he began a string of murders that ended with his arrest in 1991.

Murders

Jeffrey Dahmer committed his first murder in the summer of 1978, at the age of 18. His father was away on business and his mother had moved out, taking his brother with her; Dahmer was left behind, alone. That June, Dahmer picked up a hitchhiker named Steven Hicks and offered to drink beer with him back at his father's house, planning to eventually have sex with him. When Hicks tried to leave, Dahmer bludgeoned Hicks to death with a 10 lb. dumbell, striking the back of his head, later saying he had committed the crime because "the guy wanted to leave and [he] didn't want him to".[25] Dahmer buried the body in the backyard.[26] Nine years passed before he killed again; in September 1987, Dahmer picked up 26-year-old Steven Tuomi at a bar and killed him on impulse; he later said he had no memory of committing the crime.[20] After the Tuomi murder, Dahmer continued to kill sporadically: two more murders in 1988, and another in early 1989, usually picking up his victims in gay bars and having sex with them before killing them.[27] He kept the skull of one of his victims, Anthony Sears, until he was caught.[28]

In May 1990, he moved out of his grandmother's house for the last time and into the apartment that later became infamous: Apartment 213, 924 North 25th Street, Milwaukee. Dahmer picked up the pace of his killing: four more murders before the end of 1990, two more in February and April 1991, and another in May 1991.[29]

In the early morning hours of May 27, 1991, 14-year-old Konerak Sinthasomphone (by coincidence, the younger brother of the boy whom Dahmer had molested) was discovered on the street, wandering naked, heavily under the influence of drugs and bleeding from his rectum. Two young women from the neighborhood found the dazed boy and called 911. Dahmer chased his victim down and tried to take him away, but the women stopped him.[30] Dahmer told police that Sinthasomphone was his 19-year-old boyfriend, and that they had an argument while drinking. Against the protests of the two women who had called 911, police turned him over to Dahmer. They later reported smelling a strange scent while inside Dahmer's apartment, but did not investigate it. The smell was the body of Tony Hughes, Dahmer's previous victim, decomposing in the bedroom. The two policemen did not make any attempt to verify Sinthasomphone's age and failed to run a background check that would have revealed Dahmer was a convicted child molester still under probation.[31] Later that night, Dahmer killed and dismembered Sinthasomphone, keeping his skull as a souvenir.

By summer 1991, Dahmer was murdering approximately one person each week. He killed Matt Turner on June 30, Jeremiah Weinberger on July 5, Oliver Lacy on July 12, and finally Joseph Brandehoft on July 19. Dahmer got the idea that he could turn his victims into "zombies" — completely submissive, eternally youthful sexual partners — and attempted to do so by drilling holes into their skulls and injecting hydrochloric acid or boiling water into the frontal lobe area of their brains with a large syringe, while the victim was usually still alive.[32] Other residents of the Oxford Apartments complex noticed terrible smells coming from Apartment 213, as well as the thumps of falling objects and the occasional buzzing of a power saw.[33] Unlike many serial killers, Dahmer killed victims from a variety of racial backgrounds.

Arrest

On July 22, 1991, Dahmer lured another man, Tracy Edwards, into his home. According to the would-be victim, Dahmer struggled with Edwards in order to handcuff him, but ultimately failed to cuff his wrists together.[34] Wielding a large butcher knife, Dahmer forced Edwards into the bedroom, where Edwards saw pictures of mangled bodies on the wall and noticed the terrible smell coming from a large blue barrel.[35] Edwards punched him in the face, kicked him in the stomach, ran for the door and escaped.[36] Running through the streets, with the handcuffs still hanging from one hand, Edwards waved for help to a police car driven by Robert Rauth and Rolf Mueller of the Milwaukee police department.[37] Edwards led police back to Dahmer's apartment, where Dahmer at first acted friendly to the officers. However, Edwards remembered that the knife Dahmer had threatened him with was in the bedroom. When one of the officers checked the bedroom, he saw the photographs of mangled bodies, and called for his partner to arrest Dahmer.[38] As one officer subdued Dahmer, the other opened the refrigerator and found a human head. Further searching of the apartment revealed three more severed heads, multiple photographs of murdered victims and human remains, severed hands and penises, and photographs of dismembered victims and human remains in his refrigerator.[39]

The story of Dahmer's arrest and the inventory in his apartment quickly gained notoriety: several corpses were stored in acid-filled vats, and implements for the construction of an altar of candles and human skulls were found in his closet. Accusations soon surfaced that Dahmer had practiced necrophilia and cannibalism. Seven skulls were found in the apartment.[40] A human heart was found in the freezer.[41]

Trial

Jeffrey Dahmer was indicted on 17 murder charges, later reduced to 15. Dahmer was not charged in the attempted murder of Edwards.[citation needed] His trial began on January 30, 1992.[42] With evidence overwhelmingly against him, Dahmer pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity.[43] The trial lasted two weeks.[32] The court found Dahmer sane and guilty on 15 counts of murder and sentenced him to 15 life terms,[44] totaling 957 years in prison.[45] At his sentencing hearing, Dahmer expressed remorse for his actions, and said that he wished for his own death. In May of that year, Dahmer was extradited to Ohio, where he entered a plea of guilty for the murder of his first victim, Stephen Hicks.[46]

Imprisonment and death

Dahmer served his time at the Columbia Correctional Institution in Portage, Wisconsin, where he ultimately declared himself a born-again Christian. This conversion occurred after viewing evangelical material sent to him by his father.[47] Roy Ratcliff, a local preacher from the Churches of Christ, met with Dahmer and agreed to baptize him.[48]

Dahmer was attacked twice in prison, the first time in July 1994. An inmate attempted to slash Dahmer's throat with a razor blade while Dahmer was returning to his cell from a church service in the prison chapel. Dahmer escaped the incident with superficial wounds.[49] While doing janitorial work in the prison gym, Dahmer and another inmate, Jesse Anderson, were severely beaten by fellow inmate Christopher Scarver with a broomstick handle on November 28, 1994.[50] Dahmer died of severe head trauma while on his way to the hospital in an ambulance. Anderson died two days later from his wounds.[51] Dahmer's brain was retained for study.[52]

Aftermath

Upon learning of his death, Dahmer's mother, Joyce Flint, responded angrily to the media, "Now is everybody happy? Now that he's bludgeoned to death, is that good enough for everyone?" The response of the families of Dahmer's victims was mixed, although it appears most were pleased with his death. The district attorney who prosecuted Dahmer cautioned against turning Scarver into a folk hero, noting that Dahmer's death was still murder.[53]

After the murders, the Oxford Apartments at 924 North 25th Street were demolished; the site is now a vacant lot. Plans to convert the site into a memorial garden failed to materialize.

In 1994, Lionel Dahmer published a book, A Father's Story, and donated a portion of the proceeds from his book to the victims' families. Most of the families showed support for Lionel Dahmer and his wife, Shari. He has retired from his career as an analytical chemist and resides with his wife in Medina County, Ohio. Lionel Dahmer is an advocate for creationism, and his wife was a member of the board of the Medina County Ohio Horseman's Council.[54] Both continue to carry the name Dahmer and say they love Jeffrey despite his crimes. Lionel Dahmer's first wife, Joyce (Flint), died of cancer in 2000 at the age of 64. She was later buried in Atlanta, Georgia. Dahmer's younger brother David changed his last name and lives in anonymity.

Dahmer's estate was awarded to the families of 11 of his victims who had sued for damages. In 1996, Thomas Jacobson, a lawyer representing eight of the families, announced a planned auction of Dahmer's estate to raise up to $1 million, sparking controversy.[55][56] A civic group, Milwaukee Civic Pride, was quickly established in an effort to raise the funds to purchase and destroy Dahmer's possessions. The group pledged $407,225, including a $100,000 gift by Milwaukee real estate developer Joseph Zilber, for purchase of Dahmer's estate; five of the eight families represented by Jacobson agreed to the terms, and Dahmer's possessions were destroyed and buried in an undisclosed Illinois landfill.[57][58] [59]

In January 2007, evidence surfaced potentially linking Dahmer to Adam Walsh's 1981 abduction and murder in Florida.[12] However, Adam's father, John Walsh, believed that another serial killer, Ottis Toole, committed the crime.[60] When interviewed about Adam Walsh in the early 1990s, Dahmer repeatedly denied involvement in the crime.[12] In 2008, Florida police declared the Walsh case closed, naming Toole, who died in prison in 1996, as the killer.[61]

Known murder victims

Name Age[62] Date of death Stephen Hicks 19 Jun 6, 1978 Steven Tuomi 26 Sep 15, 1987 James "Jamie" Doxtator 14 Jan 1988 Richard Guerrero 25 Mar 24, 1988 Anthony Sears 26 Mar 25, 1989 Eddie Smith 36 Jun 1990 Ricky Beeks 27 Jul 1990 Ernest Miller 22 Sep 1990 David Thomas 23 Sep 1990 Curtis Straughter 19 Feb 1991 Errol Lindsey 19 Apr 1991 Tony Hughes 31 May 24, 1991 Konerak Sinthasomphone 14 May 27, 1991 Matt Turner 20 Jun 30, 1991 Jeremiah Weinberger 23 Jul 5, 1991 Oliver Lacy 23 Jul 12, 1991 Joseph Bradehoft 25 Jul 19, 1991 Media portrayals

- In 1992, Hart Fisher issued a $2.50 comic book titled Jeffery [sic] Dahmer: An Unauthorized Biography Of A Serial Killer. Collector's Item Issue, which the Milwaukee Sentinel described as "lurid and error-ridden." The publication sparked protests both in Milwaukee[63] and in Fisher's home town of Champaign, Illinois.[64] Dahmer's victims' relatives filed a lawsuit against Fisher (sometimes called "Fischer" in press reports) and his Boneyard Press for exploiting their loved ones' names and likenesses for profit without compensation,[65] but a court eventually ruled that since the victims were dead at the time of publication, "name or likeness" laws were not applicable.[66] In the wake of the lawsuit, Fisher eventually published sequels The Further Adventures of Young Jeffy Dahmer, Dahmer's Zombie Squad and Jeffrey Dahmer vs. Jesus Christ.[67]

- The film Jeffrey Dahmer: The Secret Life was released in 1993, starring Carl Crew as Dahmer.[68]

- Joyce Carol Oates' novel Zombie (1995) was based on Dahmer's life.[69]

- In 2002, the biopic Dahmer, starring Jeremy Renner in the title role and Bruce Davison as his father, premiered in Dahmer's hometown. The film quickly went to video.[70]

- In 2002, cartoonist John Backderf (known as Derf), who attended middle school and high school with Dahmer, produced a comic book entitled My Friend Dahmer which presents his recollections about the killer's adolescence.[71]

- In 2006, another film, Raising Jeffrey Dahmer, was released; the film stars Rusty Sneary as Dahmer and Scott Cordes as Lionel; the film revolves around the reactions of Dahmer's parents after his arrest in 1991.

- Dahmer was featured in the 6th episode of Discovery Channel's documentary series Most Evil.

References

- Dahmer, Lionel (1994). A Father's Story. William Morrow and Co. ISBN 978-0-68-812156-3. http://books.google.com/?id=Ivp2QgAACAAJ&dq=isbn=9780688121563. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- Davis, Donald (1991). The Jeffrey Dahmer Story: An American Nightmare (previously published as: The Milwaukee Murders, Nightmare in Apartment 213: The True Story). Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-31-292840-7. http://books.google.com/?id=F6tMtnYYXbEC&dq=isbn=9780312928407. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "JEFFREY DAHMER". Beacon Journal. 1994-11-29. http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=AK&s_site=ohio&p_multi=AK&p_theme=realcities&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=0EB63121D18F8CA5&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 61.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 76–79.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 80.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 82.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 90.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 105.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 107.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b c d "Did Dahmer Have One More Victim?". The Milwaukee Channel. February 1, 2007. http://www.wisn.com/news/10903529/detail.html. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 114.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 115.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 117.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 131.

- ^ a b Bardsley, Marilyn. "Jeffrey Dahmer — Serial Killer and Cannibal — Lust, Booze & Murder". TruTV.com. TruTV Crime Library. http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/dahmer/7.html. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 132.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 138.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Purcell, Catherine E.; A. Arrigo, Bruce (2006). "5". The Psychology of Lust Murder: Paraphilia, Sexual Killing, and Serial Homicide. Academic Press. p. 77. ISBN 012370510X. http://books.google.ca/books?id=agmkfIgbQxUC&pg=PA77&lpg=PA77&dq=Jeffery+Dahmer%2Bhicks&source=bl&ots=ymRSt4IgrO&sig=Ii6-iUCiSsMv8xSyTk3xhNY2Jg8&hl=en&ei=_yI5SoOuLo7qsQPc6aX-Bg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4.

- ^ Roy, Jody M. Love to Hate NY: Columbia Univ. Press, 2002; pp. 102 et seq.

- ^ Roy, Jody M. Love to Hate NY: Columbia Univ. Press, 2002; pp. 103 et seq.

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Jeffrey Dahmer — Serial Killer and Cannibal — More Murders, More Arrests". TruTV.com. TruTV Crime Library. http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/dahmer/8.html. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Jeffrey Dahmer — Serial Killer and Cannibal — The Killing Binge". TruTV.com. TruTV Crime Library. http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/dahmer/10.html. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Davis 1991, p. 7.

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Jeffrey Dahmer — Serial Killer and Cannibal — The Body in the Bedroom". TruTV.com. TruTV Crime Library. http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/dahmer/3.html. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b Dahmer 1994, p. 211.

- ^ "The Little Flat of Horrors", TIME Magazine, 5 August 1991

- ^ Davis 1991, p. 151.

- ^ Davis 1991, p. 152.

- ^ Davis 1991, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Davis 1991, p. 154.

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Jeffrey Dahmer — Serial Killer and Cannibal — Exposed!". TruTV.com. TruTV Crime Library. http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/dahmer/4.html. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Jeffrey Dahmer — Serial Killer and Cannibal — The Head in the Fridge". TruTV.com. TruTV Crime Library. http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/dahmer/5.html. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Davis 1991, p. 157.

- ^ Davis 1991, p. 158.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 207.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, pp. 209–210.

- ^ "Guilty!", TIME Magazine, 18 May 1992

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Jeffrey Dahmer — Serial Killer and Cannibal — End of the Road". TruTV.com. TruTV Crime Library. http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/dahmer/21.html. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Dahmer 1994, p. 241.

- ^ "'Creation Science' Makes a Difference." CSE Ministry. October 18, 2007.

- ^ Bardsley, Marilyn. "Jeffrey Dahmer — Serial Killer and Cannibal — Did Dahmer Find God?". TruTV.com. TruTV Crime Library. http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/dahmer/22.html. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Wisconsin Inmate help in Slaying of Dahmer." Deseret News. November 29, 1994.

- ^ "Jeffrey Dahmer, Multiple Killer, Is Bludgeoned to Death in Prison." The New York Times. November

- ^ "Dahmer Killer Charged", TIME Magazine, 15 December 1994

- ^ "Dahmer's brain kept for research." Associated Press. The Milwaukee Journal, Mar 17, 1995. Archived version.

- ^ Gleick, Elizabeth (December 12, 1994). "The Final Victim". Vol. 42 No. 24 (People Magazine). http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20104660,00.html. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ^ "Some modern scientists who have accepted the biblical account of creation". Answers in Genesis. http://www.answersingenesis.org/home/area/bios/.

- ^ Serial killer's property set to go on the auction block." CNN.com. May 8, 1996.

- ^ Johnson, Dirk. "Bid to Auction Killer's Tools Provokes Disgust." The New York Times. May 20, 1996.

- ^ "Auction of Dahmer Items Is Apparently Off." The New York Times. May 29, 1996.

- ^ O'Flaherty, Sean. "Joseph Zilber – A Gift To Milwaukee." Today's TMJ4. December 15, 2007.

- ^ "Dahmer's Possessions Destroyed." "Today's TMJ4". July 21, 2011.

- ^ "'America's Most Wanted' Host Believes Dahmer is Not Son's Killer." FoxNews.com. February 7, 2007.

- ^ Almanzar, Yolanne. "Police Expected to Close Adam Walsh Case." The New York Times. December 17, 2008.

- ^ BBC – Jeffrey Dahmer, the Milwaukee Cannibal[dead link]

- ^ Johnson-Elie, Tannette. "Dahmer comic book in demand in city" Milwaukee Sentinel May 14, 1992; pp. 1, 13A.

- ^ Williams, Celeste. "Comic book on Dahmer sparks protests" Milwaukee Journal June 14, 1992.

- ^ Read, Ben. "Victim's kin file suit over Dahmer's comic." Milwaukee Sentinel August 6, 1992.

- ^ Sheard, Chester and Cole, Jeff. "Comic book lawsuit dismissed: Court rules Dahmer-based cartoon won't infringe on victims'rights" Milwaukee Journal August 20, 1994.

- ^ Boneyard Press newspage.

- ^ "Jeffrey Dahmer: The Secret Life at imdb.com

- ^ Johnson, Greg. Invisible Writer: A Biography of Joyce Carol Oates. New York: Dutton, 1998, p. Ύ201.

- ^ Dahmer opened in theaters on June 21, 2002.[1] The DVD was released October 27.[2]

- ^ [3] "Hauling Garbage and Knowing Jeffrey Dahmer", Andrew D. Arnold, Time magazine, Apr. 16, 2002

Further reading

- Mann, Robert & Williamson, Miryam. Forensic Detective — How I Cracked The World's Toughest Cases. Ballantine Books (March 28, 2006)

- Masters, Brian. The Shrine of Jeffrey Dahmer. Hodder and Stoughton Limited, London 1993 (Paperback Coronet 1993)

- Pincus, Jonathan H. Base Instincts — What Makes Killers kill?. W.W. Norton & Company, New York 2001 (Paperback 2002)

- Ratcliff, Roy with Lindy Adams. Dark Journey, Deep Grace: The Story Behind a Serial Killer's Journey to Faith. Leafwood Publishers, (2006).

External links

Categories:- 1960 births

- 1994 deaths

- 1978 murders in the United States

- 1991 murders in the United States

- 1994 murders in the United States

- 20th-century American criminals

- American cannibals

- American members of the Churches of Christ

- American murderers of children

- American people convicted of murder

- American people who died in prison custody

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- American rapists

- American serial killers

- American sex offenders

- Converts to Christianity

- Crime in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Deaths by beating

- Human trophy collecting

- LGBT people from the United States

- Necrophiles

- Ohio State University alumni

- People convicted of murder by Wisconsin

- People from Milwaukee County, Wisconsin

- People from Summit County, Ohio

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Wisconsin

- Prisoners who died in Wisconsin detention

- Serial killers murdered in prison

- United States Army soldiers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.