- Central Otago Gold Rush

-

The Central Otago Gold Rush (often simply called the Otago gold rush) was a gold rush that occurred during the 1860s in Central Otago, New Zealand. Constituting the country's biggest gold strike, the discovery of gold in Otago led to a rapid influx of foreign miners - many of them veterans of other hunts for the precious metal in California and Victoria, Australia.

The rush started at Gabriel's Gully but spread throughout much of Central Otago, leading to the rapid expansion and commercialisation of the new colonial settlement of Dunedin, which quickly grew to be New Zealand's largest city. However, only a few years later, most of the smaller new settlements were deserted again, and gold extraction became a more commercialised, long-term activity.

Contents

Background

Previous gold finds in New Zealand

Previously gold had been found in small quantities in the Coromandel Peninsula (by visiting whalers) and near Nelson in 1842. Commercial interests in Auckland offered a £500 prize for anyone who could find payable quantities of gold anywhere nearby in the 1850s, at a time when some New Zealand settlers were leaving for the California and Australian gold rushes. In September 1852, Charles Ring, a timber merchant, claimed the prize for a find in Coromandel. A brief gold rush ensued around Coromandel township, Cape Colville and Mercury Bay but only £1500 of gold was accessible in river silt, although more was in quartz veins where it was inaccessible to individual prospectors. The rush lasted only about three months.

A find in the Aorere Valley near Collingwood in 1856 proved more successful, with 1500 miners converging on the district and removing about £150,000 of gold over the next decade, after which the gold was exhausted. The presence of gold in Otago and on the West Coast during this time was known, but the geology of the land was different from that of other major gold-bearing areas, and it was assumed the gold would amount to little.

Previous gold finds in Otago

Māori had long known of the existence of gold in Central Otago, but having no knowledge of metallurgy had no use for the ore. For a precious material they relied on greenstone for weaponry and tools, and used greenstone, obsidian and bone carving for jewellery.

The first known European discovery of gold in Otago was at Goodwood, near Palmerston in October 1851.[1] The discovery was of very small size, however, and no rush ensued. In any case, the settlement of Dunedin was just three years old, and more practical matters were of higher importance to the young town.

Further discoveries around the Mataura River in 1856 and the Dunstan Range in 1858 stirred some interest, but again this was minimal. A further discovery near the Lindis Pass in early 1861 finally started producing flickers of interest from around the South Island, with reports of large numbers of miners travelling inland from Oamaru to stake their claims. It was not until two months later, however, that the discovery which was to cause the major influx of prospectors occurred.

Main rush

Gabriel's Gully

Gabriel Read, an Australian prospector who had hunted gold in both California and Victoria, Australia, discovered gold in a creek bed at Gabriel's Gully, close to the banks of the Tuapeka River near Lawrence on 20 May 1861. "At a place where a kind of road crossed on a shallow bar I shovelled away about two and a half feet of gravel, arrived at a beautiful soft slate and saw the gold shining like the stars in Orion on a dark frosty night".[2]

The public heard about Read's discovery via a letter published in the Otago Witness on 8 June 1861, documenting a ten day long prospecting tour he had made.[3] There was little reaction at first until John Hardy of the Provincial Council stated that himself and Read had prospected country "about 31 miles long by five broad, and in every hole they had sunk they had found the precious metal."[4] With this statement, the gold rush began.

Arrival of prospectors

By Christmas 14,000 prospectors were on the Tuapeka and Waipori fields.[5] Within a year, the region's population swelled greatly, growing by 400 per cent between 1861 and 1864,[5] with prospectors swarming from the dwindling Australian goldfields. A second major discovery in 1862, close to the modern town of Cromwell, did nothing to dissuade new hopefuls, and prospectors and miners staked claims from the Shotover River in the west through to Naseby in the north. By the end of 1863, the real gold rush was over, but companies continued to mine the alluvial gold. The number of miners reached its maximum of 18,000 in February 1864.[6]

Gabriel’s Gully led to the discovery of further goldfields within Central Otago. In 1862, the Cardrona, Shotover River, Arrow River, Lake Wakatipu and the Dunstan goldfields were discovered, and also Nokomai in 1863 (Carryer, 1994).

Life in mining communities

Read’s discovery of gold sparked news to Dunedin residents and intending immigrants, informing them of gold in this area. Many left their homes and families and traveled long distances for the hope of striking it rich. These goldfields all gave rise to the construction and development of mining towns and communities. At first, these communities were temporarily built, with shops, hotels and miners huts all made from basic canvas or calico material hoisted by timber (Carryer, 1994). As the scope of the goldfields became larger, communities settled and became more permanent. The temporary canvas stores, hotels and huts previously made, were reconstructed with timber and concrete. Evidence such as material artefacts, foundations of huts and buildings, and photographs from the Central Otago goldfields provide us with information about the labour and social roles of men and women in the 19th Century.

Men in mining communities

As the news of the first discovery of gold at Gabriel’s Gully reached the citizens of Dunedin and the rest of the world, prospectors immediately left their homes in search for gold. The majority of theses prospectors were men, including such, labourers and tradesmen, in their late teens and twenties (Ell, 1995). Like many of the gold prospectors, professional businessmen made their way to the goldfields to establish services for the miners. These included stores, such as post offices, banks, pubs, hotels and hardware stores. Here, men owned these businesses, often making more money than the miners.

Evidence

Historical evidence of men as miners or businessmen in the 19th Century Central Otago goldfields is relevantly readily available. For mining men, this evidence is available in forms of literature, written records are available of when gold mines at specific locations were discovered, and by whom. Census statistics of the male population in these areas, and photographs of men at the goldfields mining are also available, all of which provide inferential evidence about the labour roles in these communities. This in turn provides information about labour and social roles within the community. Such information includes that of the ownership and management of stores and hotels, such as the bank and gold office at Maori Point (Bank of New Zealand) in the 1860s, managed by G. M. Ross (Hall-Jones, n.d.).

Archaeological evidence is also readily available. Excavations at various sites throughout Otago show evidence of an array of mining techniques, including ground sluicing, hydraulic sluicing and hydraulic elevating. Tailings (the materials left over after the removal of the uneconomic fraction (gangue) of the ore) also provide some of the archaeological evidence from Otago gold mine sites. Midden analysis from camp and settylement sites provides information about diet, with evidence of a preference for beef and lamb in the European camps, and a preference for pork within the Chinese camps.

Artefactual evidence found during excavations includes blue and white ceramics, cooking and eating utensils, metal objects, such as buttons, nails and tin boxes (flint boxes, tobacco boxes) and an exceedingly high number of alcohol glass bottles. It is possible these glass bottles were recycled, so archaeologists cannot draw definite conclusions as to alcohol consumption. Within the Chinese camps (such as the Lawrence Chinese camp) artefacts include gambling tokens and Chinese coins as well as celadon earthwares.

Although many men wrote diaries and memoirs about their lives in the mining communities, little mention or information was given about the significance of women’s labour and social roles. Archaeological evidence, however, suggests that many women on the goldfields took significant roles in both mining and the community in general.

Women in mining communities

On the 19th century goldfields, women played significant social and labour roles, as wives, mothers, prostitutes, business women and ‘Colonial Helpmeets’ (wives who worked alongside their husbands) (Dickinson, 1993). Women within these communities were young and single, or married with a family. As gold was in the midst of discovery, many wives and children of the male prospectors did not travel in search of gold to begin with. These wives and children moved to the goldfields as towns developed with hotels, stores and schools. However, women were present on these goldfields from the very first discovery of gold in 1861, at Gabriel’s Gully. An example is Janet Robertson, who lived with her husband in a small cottage in Tuapeka. It was here in her cottage, where Gabriel Read wrote his discovery letter of gold to the Otago Provincial Council (Dickinson, 1993). As the news of this goldfield in Gabriel's Gully spread, prospectors engaged in the area, and Janet opened up her home, cooked meals and tended to the miners, as they passed through.

Evidence of another significant women present on the 19th Century Central Otago goldfields, was Susan Nugent-Wood, a well known writer in the 1860s and 1870s. Nugent-Wood, her husband John, and their children moved to Otago in 1861, as prospectors of gold. Nugent-Wood worked on the goldfields of Central Otago in several official positions (Smith, 2007). She wrote stories based on her life and roles on the Central Otago goldfields. These provide accounts of labour and social aspects of mining and gender in the 19th Century.

As the majority of women within these mining communities were married, many became widows, as their husbands died during mining related activities or diseases. These women, whose husbands owned stores or hotels, adopted ownership rights (Ell, 1995). Many became well known throughout the communities, amongst visitors, passing miners and local citizens. Archaeological evidence of a widow, who took over ownership rights following her husbands’ death, was Elizabeth Potts. Potts was given a legitimate license for the Victoria Hotel in Lawrence in 1869 (Tuapeka Times, 1869). This was recorded and published in the Tuapeka Times, 11 December 1869. This archaeological evidence provides information which suggests that women played significant labour and social roles within mining communities.

Excavation evidence

An excavation report written by P. G. Petchey, from the Golden Bar Mine between the Macraes Flat and Palmeston, Otago, shows that located in front of the main mine workings of ca.1897, archaeological material was found. This material was a small heart-shaped broach with 13 glass diamonds (Petchey, 2005). This archaeological evidence suggests that women were present at this site, and within the Golden Bar goldfield. The exact occupation of women from this evidence is unknown, but indicates that women were present on the goldfields during the 19th Century gold rush in Otago.

Another excavation report by Petchey from the Macraes Flat mining area, presents items of children’s toys such as marbles, and a china doll’s leg amongst ruins of a house site (Petchey, 1995). This evidence is also useful to suggest men and their families engaged in mining activities and social life on the goldfields in the 19th Century. Archaeological artefacts from 19th Century mining communities in Central Otago, suggest women and children were on site of the goldfields. It is unknown whether these artefacts belong to women who were miners or women who were domestic wives and mothers.

Aftermath

Results

The city of Dunedin reaped many of the benefits, briefly becoming New Zealand's largest town even though it had only been founded in 1848. Many of the city's stately buildings date from this period of prosperity. New Zealand's first university, the University of Otago, was founded in 1869 with wealth derived from the goldfields.

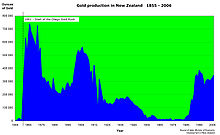

However, the rapid decline in gold production from the mid 1860s led to a sharp drop in the province's population, and while not unprosperous, the far south of New Zealand never rose to such relative prominence again.

Later gold rushes

Main article: West Coast Gold RushThe Wakamarina River in Marlborough proved to have gold in 1862, and 6,000 miners flocked to the district. Although they found alluvial gold, there were no large deposits.

The West Coast of the South Island was the second-richest gold-bearing area of New Zealand after Otago, and gold was discovered in 1865-6 at Okarito, Bruce Bay, around Charleston and along the Grey River. Miners were attracted from Victoria, Australia where the gold rush was near an end. In 1867 this boom also began to decline, though gold mining continued on the coast for a considerable time after this. In the 1880s, quartz miners at Bullendale and Reefton were the first users of electricity in New Zealand.[7]

Southland also had a number of smaller scale gold rushes during the later half of the 19th century. The first goldmining in Southland took place in 1860 on the banks of the Mataura River and its tributaries (and later would help settlements such as Waikaia and Nokomai flourish). However the first "gold rush" wasn't until the mid-1860s when fine gold was discovered in the black sands of Orepuki beach. Miners followed the creeks up into the foothills of the Longwoods to where the richest gold was to be had. This activity led to the founding of mining settlements such as Orepuki and Round Hill (the Chinese miners and shop owners essentially ran their own town known colloquially to Europeans as "Canton").

Gold was long known to exist at Thames, but exploitation was not possible during the New Zealand land wars. In 1867 miners arrived from the West Coast, but the gold was in quartz veins, and few miners had the capital needed to extract it. Some stayed on as workers for the companies which could fund the processing.

Commercial extraction

After the main gold rush, miners began laboriously reworking the goldfields. About 5,000 European miners remained in 1871, joined by thousands of Chinese miners invited by the province to help rework the area. There was friction not only between European and Chinese miners, which contributed to the introduction of the New Zealand head tax, but also between miners and settlers over conflicting land use.

Attention turned to the gravel beds of the Clutha River, with a number of attempts to develop a steam-powered mechanical gold dredge. These finally met with success in 1881 when the Dunedin became the world's first commercially successful gold dredge.[8] The Dunedin continued operation until 1901, recovering a total of 17,000 ounces (530 kg) of gold.

The mining has had a considerable environmental impact. In 1920 the Rivers Commission estimated that 300 million cubic yards of material had been moved by mining activity in the Clutha river catchment. At that time an estimated 40 million cubic yards had been washed out to sea with a further 60 million in the river. (The remainder was still on riverbanks). This had resulted in measured aggradation of the river bottom of as much as 5 metres.[9]

Gold is still mined by OceanaGold in commercial quantities in Otago at one site - Macraes Mine inland from Palmerston, which started operations in 1990. Macraes Mine, an opencast hard rock mining operation, processes more than 5 million tonnes of ore per year and had extracted 1.85 million ounces (57,500 kg) of gold by 2004.[10]

The Otago gold rush in popular culture

Numerous folk songs, both contemporary and more recent, have been written about the gold rush. Of contemporary songs, "Bright Fine Gold", with its chorus of "Wangapeka, Tuapeka, bright fine gold" (sometimes rendered "One-a-pecker, two-a-pecker") is perhaps the best known.[11] Most well-known of more recent songs is arguably Phil Garland's song Tuapeka Gold.[12]

Martin Curtis wrote a folk-style song about the gold rush called "Gin and Raspberry." The lyrics are written in the voice of an unsuccessful gold prospector who envies the success of the largest gold mine in the Cardrona valley at the time, the "Gin and Raspberry" (supposedly so named because the owner would call out, "Gin and raspberry to all hands!" whenever a bucket of mined material yielded an ounce of gold. The singer laments, "an ounce to the bucket and we'd all sell our souls/For a taste of the gin and raspberry." The song has had several recordings, particularly by Gordon Bok.[13][14]

See also

- Mining in New Zealand

- West Coast Gold Rush

- Gold Fields (New Zealand electorate)

- Goldfields Towns (New Zealand electorate)

- Archaeological evidence of gender in Central Otago mining communities

References

- ^ Reed, A.H. (1956). The Story of Early Dunedin. Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed. p.257.

- ^ Miller, p. 757

- ^ "Lindis Gold Fields". Otago Witness: p. 5. Issue 497, 8 June 1861. http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=OW18610608.2.21. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ Miller, p. 758

- ^ a b McLean & Dalley, p. 156

- ^ McKinnon, M. (ed.) (1997). New Zealand Historical Atlas: Ko Papatuanuku e Takoto Nei Auckland: David Bateman Ltd. pl.45. ISBN 1-86953-335-6

- ^ McKinnon, M. (ed.) (1997). New Zealand Historical Atlas: Ko Papatuanuku e Takoto Nei Auckland: David Bateman Ltd. pl.44. ISBN 1-86953-335-6

- ^ Gold in New Zealand: The Early Years (from New Zealand Mint website, retrieved 15 August 2006)

- ^ Channel morphology and sedimentation in the Lower Clutha River. Otago Regional Council. July 2008. ISBN 1-877265-59-4. http://www.orc.govt.nz/Documents/ContentDocuments/env_monitoring/Clutha%20River%20Channel%20Morphology_.pdf.

- ^ Macraes Mine: Highlights (from the OceanaGold company website, retrieved 7 January 2007)

- ^ [1]. The Wangapeka River, in the northwestern South island, was the site of another, smaller gold rush.

- ^ [2]

- ^ Lyrics and discography

- ^ A discussion of Cardrona that includes mining history

Further reading

- Eldred-Grigg, Stevan (2008). Diggers, Hatters & Whores - The Story of the New Zealand Gold Rushes. Auckland: Random House. pp. 543 pages.. ISBN 978-1-86941-925-7.

- King, M. (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand', ISBN 0-14-301867-1

- McLaughlan, G. (ed.) (1995). Bateman New Zealand Encyclopedia (4th ed.). Auckland: David Bateman Ltd.

- McLean, G. & Dalley, B. (eds.) Frontier of Dreams: The Story of New Zealand. Auckland: Hodder Moa Beckett. ISBN 1-86971-006-1

- Miller, F.W.G. (1971). "Gold in Otago", in Knox, R. (ed.) New Zealand's Heritage, volume 2:. Wellington:Paul Hamlyn.

- Oliver, W.H. (ed.) (1981). The Oxford History of New Zealand. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-558063-X

On life in mining communities

- Carryer, B. (1994). The New Zealand GoldRushes, 1860–1870, Berkley Publishing, Browns Bay, Auckland, pp 5–6, 19.

- Dickinson, J. (1993). ‘Picks, pans and petticoats: Women on the Central Otago goldfields’, BA(HONS) dissertation, Otago University, New Zealand.

- Ell, G. (1995). GoldRush: Tales and Traditions of the New Zealand Goldfield, The Bush Press, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Forrest, J. (1961). Population and Settlement on the Otago Goldfields 1861-1870, New Zealand Geographer, 17, 1, pp64–86.

- Glasson, H. A. (1957). The Golden Cobweb: a saga of the Otago goldfields, 1861–1864, Otago Daily Times & Witness Newspapers, Dunedin.

- Hall-Jones, J. Goldfields of Otago: An Illustrated History, Craig Printing Co. Ltd, Invercargill, New Zealand, pp 122.

- Harper, B. (1980). Petticoat Pioneers: South Island women of the Colonial Era, A. H. & A. W. REED LTD, Wellington, New Zealand pp184–189.

- Mahalski, B. (2005). New Zealand’s Golden Days, Gilt Edge Publishing, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Petchey, P. G. (1995). Excavation Report Site 142/27: House Sites Site142/28: Stone Ruin Macraes Flat: For Macraes Mining Company, Dunedin, pp 10.

- Petchey, P. G. (2005). Golden Bar Mine Macraes: Report for Oceana Gold Ltd, Southern Archaeology, Dunedin, pp 34.

- Smith, Rosemarie. "Wood, Susan 1836–1880". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1w37. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Tuapeka Times. (1869, December 11). Licensing Meeting, pp 3.

External links

Categories:- Otago Gold Rush

- History of the Otago Region

- 1851 in New Zealand

- 1861 in New Zealand

- Clutha River

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.