- Woodblock printing in Japan

-

For woodblock printing in general, see Woodblock printing.

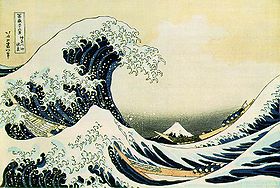

Woodblock printing in Japan (Japanese: 木版画, moku hanga) is a technique best known for its use in the ukiyo-e artistic genre; however, it was also used very widely for printing books in the same period. Woodblock printing had been used in China for centuries to print books, long before the advent of movable type, but was only widely adopted in Japan surprisingly late, during the Edo period (1603-1867). Although similar to woodcut in western printmaking in some regards, moku hanga differs greatly in that water-based inks are used (as opposed to western woodcut which uses oil-based inks), allowing for a wide range of vivid color, glazes and color transparency.

Contents

History

Woodblock-printed books from Chinese Buddhist temples were seen in Japan as early as the eighth century. In 764 the Empress Shotuku commissioned one million small wooden pagodas, each containing a small woodblock scroll printed with a Buddhist text (Hyakumanto Darani). These were distributed to temples around the country as thanksgiving for the suppression of the Emi Rebellion of 764.[1] These are the earliest examples of woodblock printing known, or documented, from Japan.

By the eleventh century, Buddhist temples in Japan were producing their own printed books of sutras, mandalas, and other Buddhist texts and images. For centuries, printing was restricted only to the Buddhist sphere, as it was too expensive for mass production, and did not have a receptive, literate public to which such things might be marketed.

It was not until 1590 that the first secular work would be printed in Japan. This was the Setsuyō-shū, a two-volume Chinese-Japanese dictionary. Though the Jesuits operated a movable type printing press in Nagasaki from 1590[2], printing equipment brought back by Toyotomi Hideyoshi's army from Korea in 1593 had far greater influence on the development of the medium. Four years later, Tokugawa Ieyasu, even before becoming shogun, effected the creation of the first native moveable type, using wooden type-pieces rather than metal. He oversaw the creation of 100,000 type-pieces, which were used to print a number of political and historical texts. As shogun, Ieyasu would act to promote literacy and learning, leading to the beginnings of the emergence of an educated urban public. Printing was not dominated by the shogunate at this point, however; private printers appeared in Kyoto at the beginning of the 17th century, and Toyotomi Hideyori, Ieyasu's primary political opponent, aided in the development and spread of the medium as well. An edition of the Confucian Analects was printed in 1598, using a Korean moveable type printing press, at the order of Emperor Go-Yōzei. This document is the oldest work of Japanese moveable type printing extant today. Despite the appeal of moveable type, however, it was soon decided that the running script style of Japanese writings would be better reproduced using woodblocks, and so woodblocks were once more adopted; by 1640 they were once again being used for nearly all purposes.

The medium quickly gained popularity among artists, and was used to produce small, cheap, art prints as well as books. The great pioneers in applying this method to the creation of art books, and in preceding mass production for general consumption, were Honami Kōetsu and Suminokura Soan. At their studio in Saga, the pair created a number of woodblocks of the Japanese classics, both text and images, essentially converting handscrolls to printed books, and reproducing them for wider consumption. These books, now known as Kōetsu Books, Suminokura Books, or Saga Books, are considered the first and finest printed reproductions of many of these classic tales; the Saga Book of the Tales of Ise (Ise monogatari), printed in 1608, is especially renowned.

Woodblock printing, though more tedious and expensive than later methods, was far less so than the traditional method of writing out each copy of a book by hand; thus, Japan began to see something of literary mass production. While the Saga Books were printed on expensive fancy paper, and used various embellishments, being printed specifically for a small circle of literary connoisseurs, other printers in Kyoto quickly adapted the technique to producing cheaper books in large numbers, for more general consumption. The content of these books varied widely, including travel guides, advice manuals, kibyōshi (satirical novels), sharebon (books on urban culture), art books, and play scripts for the jōruri (puppet) theatre. Often, within a certain genre, such as the jōruri theatre scripts, a particular style of writing would come to be the standard for that genre; in other words, one person's personal calligraphic style was adopted as the standard style for printing plays.

Many publishing houses arose and grew, publishing both books and individual prints. One of the most famous and successful was called Tsuta-ya. A publisher's ownership of the physical woodblocks used to print a given text or image constituted the closest equivalent to a concept of "copyright" that existed at this time. Publishers or individuals could buy woodblocks from one another, and thus take over the production of certain texts, but beyond the protective ownership of a given set of blocks (and thus a very particular representation of a given subject), there was no legal conception of the ownership of ideas. Plays would be adopted by competing theatres, and either reproduced wholesale, or individual plot elements or characters might be adapted; this activity was considered legitimate and routine, at the time.

Woodblock printing continued to be used after the decline of ukiyo-e, and the introduction of movable type and other technologies, as a method and medium for printing texts as well as for producing art, both within traditional modes such as ukiyo-e and in a variety of more radical or Western forms that might be construed as modern art.

Technique

The technique for printing texts and images was generally quite similar; the obvious differences being in the volume produced when working with texts (many pages for a single work), and the complexity of multiple colors that might be encountered when working with images. Images in books were almost always in monochrome (black ink only), and for a time art prints were likewise monochrome or done in only two or three colors.

The text or image would first be drawn onto washi (Japanese paper), and then glued onto a plank of wood, usually cherry. Wood would then be cut away, based on the outlines given by the drawing. A small wooden hard object called a baren would be used to press or burnish the paper against the inked woodblock, thus applying the ink onto the paper. Although this may have been done purely by hand at first, complex wooden mechanisms were soon invented and adopted to help hold the woodblock perfectly still and to apply proper pressure in the printing process. This would be especially helpful once multiple colors began to be introduced, and needed to be applied with precision atop previous ink layers.

While, again, text was nearly always monochrome, as were images in books, the growth of the popularity of ukiyo-e brought with it demand for ever increasing numbers of colors and complexity of techniques. The stages of this development follow.

- Sumizuri-e (墨摺り絵, "ink printed pictures") - monochrome printing using only black ink

- Benizuri-e (紅摺り絵, "crimson printed pictures") - red ink details or highlights added by hand after the printing process;green was sometimes used as well

- Tan-e (丹絵) - orange highlights using a red pigment called tan

- Aizuri-e (藍摺り絵, "indigo printed pictures"), Murasaki-e (紫絵, "purple pictures"), and other styles in which a single color would be used in addition to, or instead of, black ink

- Urushi-e (漆絵) - a method in which glue was used to thicken the ink, emboldening the image; gold, mica and other substances were often used to enhance the image further. Urushi-e can also refer to paintings using lacquer instead of paint; lacquer was very rarely if ever used on prints.

- Nishiki-e (錦絵, "brocade pictures") - a method in which multiple blocks were used for separate portions of the image, allowing a number of colors to be utilized to achieve incredibly complex and detailed images; a separate block would be carved to apply only to the portion of the image designated for a single color. Registration marks called kentō (見当) were used to ensure correspondence between the application of each block.

Schools and movements

"Shōki zu" (Shōki striding), by Okumura Masanobu, c. 1741-1751. An example of pillar print format originally 69.2 x 10.1 cm.

"Shōki zu" (Shōki striding), by Okumura Masanobu, c. 1741-1751. An example of pillar print format originally 69.2 x 10.1 cm.

Japanese printmaking, as many other features of Japanese art, tended to organise itself into schools and movements. The most notable schools and, later, movements of moku hanga were:

- Torii school, from 1700

- Kaigetsudō school, from 1700-14

- Katsukawa school, from about 1740, including the artists Suzuki Harunobu and Hokusai

- Utagawa school, from 1842, including the artist Kunisada

- Sōsaku hanga, "Creative Prints" movement, from 1904

- Shin hanga "New Prints" movement, from 1915

Other artists, such as Utamaro, Sharaku, and Hiroshige did not belong to a specific school, and drew from a wider tradition.

Paper sizes

There were a number of standard sizes for prints in the Edo period, some of which follow. (All centimeter measurements are approximate.)

- Chūban (中判, middle size)(26x19cm)

- Chūtanzaku (中短冊)(38x13cm) - also known simply as tanzaku; half of an ōban, cut lengthwise

- Hashira-e (柱絵)(68-73 x 12-16 cm) - a narrow, upright format often called "pillar prints"

- Hosoban (細判)(33x15cm) - several hosoban would be cut from an ō-ōban (大大判, large large size); hosoban was the smallest of the common sheet sizes.

- Kakemono-e (掛物絵)(76.5x23cm) - large, upright format comprised approximately of two ōban arranged one above the other. Kakemono also refers to hanging scroll paintings.

- Ōban (大判, large size)(39x26.5 cm) - the most common sheet size.

- Ō-hosoban (大細判)(38x17cm) - also known as Ō-tanzaku

- Shikishiban (21 x 18 cm) often used for surimono

The Japanese terms for vertical (portrait) and horizontal (landscape) formats for images are tate-e (立て絵) and yoko-e (横絵), respectively.

Notes

- ^ http://www.schoyencollection.com/Pre-Gutenberg.htm#2489

- ^ Fernand Braudel, "Civilization & Capitalism, 15-18th Centuries, Vol 1: The Structures of Everyday Life," William Collins & Sons, London 1981

References

- Forrer, Matthi, Willem R. van Gulik, Jack Hillier A Sheaf of Japanese Papers, The Hague, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, 1979. ISBN 9070265710

- Kaempfer, H. M. (ed.), Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, A Collection of Essays on the Art of Japanese Prints, The Hague, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, 1978. ISBN 9070216019

- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 10-ISBN 0-674-01753-6; 13-ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 48943301

- Friese, Gordon (2007). "Hori-shi. 249 facsimiles of different seals from 96 Japanese engravers." Unna, Nordrhein-Westfalen: Verlag im bücherzentrun.

- Lane, Richard. (1978). Images from the Floating World, The Japanese Print. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10-ISBN 0192114476/13-ISBN 9780192114471; OCLC 5246796

- Sansom, George (1961). "A History of Japan: 1334-1615." Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

See also

- Engelbert Kaempfer- early German traveller to Japan

- History of printing in East Asia

- List of ukiyo-e terms

- Printmaking

- Surimono

- Woodblock printing

- Woodcut

- Uki-e

External links

- Ukiyo-e Caricatures 1842-1905 Database of the Department of East Asian Studies of the University of Vienna

- The process of woodblock printing Movie by Adachi Woodcut Print

- Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, University of California, San Francisco

- Contemporary Japanese prints from the 50th anniversary of the College Women's Association of Japan Print Show

Categories:- Japanese art

- Ukiyo-e

- Relief printing

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.