- Cadency

-

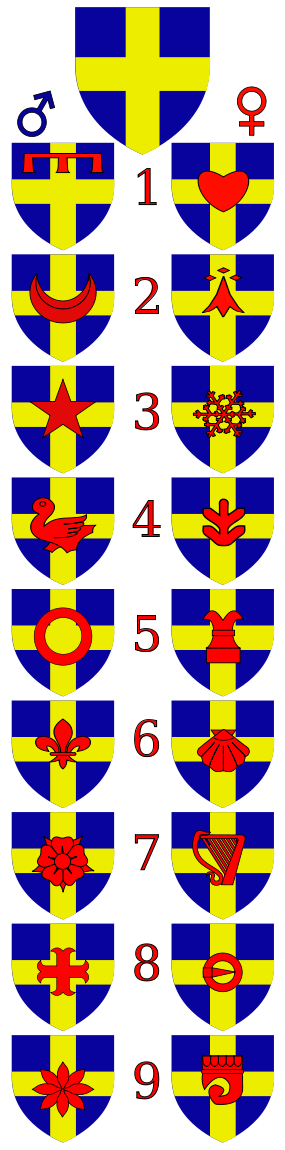

Brisures used in cadency (shown in red). The left-hand column shows the cadency marks (brisures) used for sons in the English and Canadian systems. The right-hand column shows the brisures used in Canadian heraldry for daughters.The marks are usually very much smaller than shown, and the fourth son's cadency mark is not the continental merlette but the British Isles martlet

Brisures used in cadency (shown in red). The left-hand column shows the cadency marks (brisures) used for sons in the English and Canadian systems. The right-hand column shows the brisures used in Canadian heraldry for daughters.The marks are usually very much smaller than shown, and the fourth son's cadency mark is not the continental merlette but the British Isles martlet

In heraldry, cadency is any systematic way of distinguishing similar coats of arms belonging to members of the same family. Cadency is necessary in heraldic systems in which a given design may be owned by only one person (or, in some cases, one man) at once. Because heraldic designs may be inherited, the arms of members of a family will usually be similar to the arms used by its oldest surviving member (called the "plain coat"). They are formed by adding marks called brisures, similar to charges but smaller. Brisures are generally exempt from the rule of tincture.

Contents

Systems of cadency

In heraldry's early period, uniqueness of arms was obtained by a wide variety of devices, including change of tincture and addition of an ordinary. See Armorial des Capétiens and Armorial of Plantagenet for an illustration of the variety.

Systematic cadency schemes were later developed in England and Scotland, but while in England they are voluntary (and not always observed), in Scotland they are enforced through the statutorily required process of matriculation in the Public Register.

England

The English system of cadency involves the addition of these brisures to the plain coat:

- for the first son, a label of three points (a horizontal strip with three tags hanging down)—this label is removed on the death of the father, and the son inherits the plain coat;

- for the second son, a crescent (the points upward, as is conventional in heraldry);

- for the third son, a mullet (a five-pointed star);

- for the fourth son, a martlet (a kind of bird);

- for the fifth son, an annulet (a ring);

- for the sixth son, a fleur-de-lys;

- for the seventh son, a rose;

- for the eighth son, a cross moline;

- for the ninth son, a double quatrefoil.

Daughters have no special brisures, and use their father's arms on a lozenge. This is because English heraldry has no requirement that women's arms be unique.

In England, arms are generally the property of their owner from birth - subject to the use of the appropriate mark of cadency. In other words, it is not necessary to wait for the death of the previous generation before arms are inherited.

The eldest son of an eldest son uses a label of five points. Other grandchildren combine the brisure of their father with the relevant brisure of their own, which would in a short number of generations lead to confusion (because it allows an uncle and nephew to have the same cadency mark) and complexity (because of an accumulation of cadency marks to show, for example, the fifth son of a third son of a second son). However, in practice cadency marks are not much used in England and, even when they are, it is rare to see more than one or, at most, two of them on a coat of arms.

Although textbooks on heraldry (and articles like this one) always agree on the English system of cadency set out above, most heraldic examples (whether on old bookplates, church monuments, silver and the like) ignore cadency marks altogether. Oswald Barron, in an influential article on Heraldry in the 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, noted:

- "Now and again we see a second son obeying the book-rules and putting a crescent in his shield or a third son displaying a molet, but long before our own times the practice was disregarded, and the most remote kinsman of a gentle house displayed the "whole coat" of the head of his family."[1]

Nor have cadency marks usually been insisted upon by the College of Arms (the heraldic authority for England, Wales and formerly Ireland). For example, the College of Arms website (as of June 2006), far from insisting on any doctrine of "One man one coat" suggested by some academic writers, says:

- … The arms of a man pass equally to all his legitimate children, irrespective of their order of birth.

- Cadency marks may be used to identify the arms of brothers, in a system said to have been invented by John Writhe, Garter, in about 1500. Small symbols are painted on the shield, usually in a contrasting tincture at the top. …[2]

It does not say that such marks must be used.

In correspondence published in the Heraldry Society’s newsletter, Garter King of Arms Peter Gwynn-Jones firmly rejected a suggestion that cadency marks should be strictly enforced. He said:

- “I have never favoured the system of cadency unless there is a need to mark out distinct branches of a particular family. To use cadency marks for each and every generation is something of a nonsense as it results in a pile of indecipherable marks set one above the other. I therefore adhere to the view that they should be used sparingly”.[3]

In a second letter published at the same time, he wrote:

- “Unfortunately, compulsion is not the way ahead for twenty-first century heraldry. However, official recognition and certification of any Armorial Bearings can only be effected when the person in whose favour the Arms are being recognized or certified appears in the appropriate book of record at the College of Arms. I believe it right in England and Wales for a branch to use cadency marks sparingly and only if they wish to do so.”[4]

Scotland

The system is very different in Scotland, where every male user of a coat of arms may only use arms recorded (or "matriculated") in the Public Register with a personal variation, appropriate to that person's position in their family, approved by the Lord Lyon (the heraldic authority for Scotland). This means that in Scotland no two men can ever simultaneously bear the same arms, even by accident, if they have submitted their position to the Scottish heraldic authorities (which not all do in practice, in Scotland as in England); if they have not done so, the matter falls under statute law and may result in proceedings in the Lyon Court, which is part of the Scots criminal justice system. To this extent, the law of arms is stricter in Scotland than in England where the only legal action possible is a civil action in the Court of Chivalry, which sits extremely rarely and is not an integrated part of the English justice system.

Scotland, like England, uses the label of three points for the eldest son (or heir presumptive) and a label of five points for the eldest son of the eldest son, and allows the label to be removed as the bearer of the plain coat dies and the eldest son succeeds.

For cadets other than immediate heirs, Scottish cadency uses a complex and versatile system, applying different kinds of changes in each generation. First, a bordure is added in a different tincture for each brother. In subsequent generations the bordure may be divided in two tinctures; the edge of the bordure, or of an ordinary in the base coat, may be changed from straight to indented, engrailed or invected; charges may be added. These variations allow the family tree to be expressed clearly and unambiguously. (The system outlined here is a very rough version that gives a flavour of the real thing).

In the Scots heraldic system (which has little to do with the clan system), only one bearer of any given surname may bear plain arms. Other armigerous persons with the same surname usually have arms derived from the same plain coat; though if actual kinship cannot be established, they must be differenced in a way other than the cadency system mentioned above. This is quite unlike the English system, in which the surname of an armiger is generally irrelevant.

Canada

Canadian cadency generally follows the English system. However, since in Canadian heraldry a coat of arms must be unique regardless of the bearer's gender, Canada has developed a series of brisures for daughters unique to Canada:[5]

- for the first daughter, a heart;

- for the second daughter, an ermine spot;

- for the third daughter, a snowflake;

- for the fourth daughter, a fir twig;

- for the fifth daughter, a chess rook

- for the sixth daughter, an escallop (scallop shell);

- for the seventh daughter, a harp;

- for the eighth daughter, a buckle;

- for the ninth daughter, a clarichord.

The actual practice in Canada is far from the rigidity suggested by the list of differences above - and is best seen in action in the Canadian Public Register - see for example the coats of various Armstrongs and Bradfords.

South Africa

Personal arms granted by the South African Heraldic Authority have the option of being differenced (but this is not compulsory) upon matriculation by the Authority, and the systems used vary, for the brisures used in the English system, to substitution of different charges, to changing of tinctures.

Republic of Ireland

The brisures used in the arms granted by the Chief Herald of the Republic of Ireland are identical to the brisures used by the system used in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, but unlike the English system, which only uses these brisures for the sons of an armiger in order of birth, the Irish system applies them to all the children of the armiger, irrespective of gender, and, as illegitimacy has no place in Irish heraldry, these marks are assigned to (recognised) children born outside of marriage as well as inside.

The British Royal Family

Main article: Royal Labels of the United Kingdom

Arms of

The Queen

Arms of the

Prince of WalesArms of the

Duke of CambridgeArms of

Prince HarryArms of the

Duke of YorkArms of

Princess BeatriceArms of

Princess Eugenie

Arms of the

Earl of WessexArms of the

Princess RoyalArms of the

Duke of GloucesterArms of the

Duke of KentArms of

Prince MichaelArms of

Princess AlexandraThere are no actual "rules" for members of the Royal Family, because their arms are theoretically decided ad hoc by the sovereign. In practice, however, a number of traditions are practically invariably followed. At birth, members of the Royal Family have no arms. At some point during their lives, generally at the age of eighteen, they may be granted arms of their own. These will always be the arms of dominion of the Sovereign with a label argent for difference; the label may have three or five points. Since this is in theory a new grant, the label is applied not only to the shield but also to the crest and the supporters to ensure uniqueness. Though de facto in English heraldry the crest is uncharged (although it is supposed to be in theory), as it would accumulate more and more cadency marks with each generation, the marks eventually becoming indistinguishable, the crests of the Royal Family are always shown as charged.

Each Prince of Wales uses a plain white label and (since 1911) an inescutcheon of the ancient arms of the Principality of Wales. Traditionally, the other members of the family have used a stock series of symbols (cross of Saint George, heart, anchor, fleur-de-lys, etc.) on the points of the label to ensure that their arms differ. The labels of The Duke of Cambridge and Prince Harry have one or more scallop shells taken from the arms of their mother, Diana, Princess of Wales;[6] this is sometimes called an innovation but in fact the use of maternal charges for difference is a very old practice, illustrated in the "border of France" (azure semé-de-lys or) borne by John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall (1316–36), younger son of Edward II of England and Isabella of France.

It is often said that labels argent are a peculiarly royal symbol, and that eldest sons outside the royal family should use labels of a different colour, usually gules.

Continental usages

France

The Former Royal House

Arms of Henri,

Count of Paris and Duke of FranceArms of Jean,

Dauphin and Duke of Vendôme, second son of Henri.Arms of Jacques,

Duke of Orléans, brother of HenriArms of Charles-Philippe,

Duke of Anjou and Cavadal, nephew of Henri.Arms of Eudes,

Duke of Angoulême, third son of Henri.Arms of Michel,

Count of Evreux, brother of Henri and father of Charles-Philippe.During the Middle Ages, marks of cadency were used extensively by armigers in France, as can be seen in the Armorial de Gelre. By the eighteenth century, such marks were no longer used by the members of armigerous families, but were still used extensively by the members of the French Royal Family.

The French Revolution of 1789 had a profound impact on heraldry, and heraldry was abolished in 1790, to be restored in 1808 by Napoleon I. However, Napoleon's heraldic system did not use marks of cadency either; the decree of March 3, 1810 (art. 11) states: "The name, arms and livery shall pass from the father to all sons" although the distinctive marks of Napoleonic titles could pass only to the sons who inherited them.

No subsequent regime in France ever promulgated any legislation regarding marks of difference in heraldry, so they remain unused (except in the heraldry of the former Royal family, as can be seen above).

Germany

German noble houses generally do not use differencing marks to denote separate branches of the same house. Rather, all members of the house use the same, identical shield with a different crest or crests.[citation needed]

An exception is the House of Hohenzollern, which at times used a system of bordures.

Italy

The Former Royal House

Arms of Vittorio Emanuele, Prince of Naples, Head of the Royal House. Since 2006 these arms have also been borne by his distant cousin and rival to the Headship of the House, Amadeo of Aosta Arms of Emanuele Filiberto the Prince of Venice and Piedmont Arms of the (extinct) branch of the

Duke of GenoaArms of the

Duke of Aosta until 2006.Belgium

Arms of the King. Arms of Philippe,

Duke of Brabant eldest son of the King.Arms of all agnatic male-line issue of King Leopold III, including the King before his accession to the throne, except those with the title of Duke of Brabant. Arms of Charles,

Count of Flanders (d.1983), uncle of the King.Arms of all Princesses of Belgium. Danish Royal Family

Coat of arms of Queen Margrethe II Coat of arms of Frederik, Crown Prince of Denmark, these arms are identical to those of the Queen, but the external ornaments are different. Arms of

Prince Joachim of Denmark, identical to the arms of the Queen and Prince Frederik, but the inescutcheon is parted per pale Oldenburg and Laborde de Monpezat, his father's family.Arms of

Prince Henrik of Denmark; father of Princes Frederik and JoachimArms of the sisters of Queen Margrethe II, Princesses Anne Marie (formerly Queen of the Hellenes)and Benedikte; also borne by the Queen prior to her accession. These arms are the same as those of the late Frederik IX, only with differing external ornaments. The Netherlands

The Royal House

Portugal

Royal House

Arms of the

KingArms of the

QueenArms of the

Prince RoyalArms of the

Prince of BeiraArms of the

First InfanteArms of the

Second InfanteArms of the

Third InfanteArms of a

InfantaSpain

Royal Family

Arms of the

KingArms of the

Prince of AsturiasArms of the

Duchess of LugoArms of the

Duchess of PalmaArms of the

Duchess of BadajozArms of the

Duchess of Soria [14]Sweden

The Royal House

References

- ^ Oswald Barron, s.v. Heraldry, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1911

- ^ [1]

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette December 2007 New Series 106 pp 8-9

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette December 2007 New Series 106 p 9

- ^ Heraldry proficiency program - Canadian Heraldic Information (April 5, 2007) Heraldry.ca. Accessed 2008-08-28.

- ^ Arms of Princes William and Harry, showing differencing

- ^ Ottfried Neubecker, Roger Harmingues, Le Grand livre de l'héraldique, Bordas, 1976 (réimpr. 1982), 288 p. ISBN 2-04-012582-5.

- ^ http://www.heraldica.org/topics/france/roygenea.htm

- ^ (French) Heraldique Europeenne Accessed 2009-04-18.

- ^ Jiri Louda, Michael Maclagan, Les Dynasties d'Europe, Bordas, 1981 (réimpr. 1993), p. 242-243. ISBN 2-04-027013-2 .

- ^ Ottfried Neubecker, Roger Harmingues.

- ^ (French) Heraldique Europeenne Accessed 2009-04-18.

- ^ Jiri Louda, Michael Maclagan, Les Dynasties d'Europe, Bordas, 1981 (réimpr. 1993), p. 242-243. ISBN 2-04-027013-2 .

- ^ (Spanish) La Brisura en la Casa Real - Blog de Heraldica Accessed 2009-04-18.

- ^ (French) Heraldique Europeenne Accessed 2009-04-18.

- ^ Jiri Louda, Michael Maclagan, Les Dynasties d'Europe, Bordas, 1981 (réimpr. 1993), p. 242-243. ISBN 2-04-027013-2 .

Heraldry Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.