- Wahine disaster

-

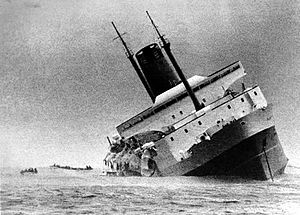

The TEV Wahine lists heavily to starboard as it sinks in Wellington Harbour. Lifeboats from the ship can be seen to the left.

The TEV Wahine lists heavily to starboard as it sinks in Wellington Harbour. Lifeboats from the ship can be seen to the left.

The Wahine disaster occurred on 10 April 1968 when the TEV Wahine, a New Zealand inter-island ferry of the Union Company, foundered on Barrett Reef at the entrance to Wellington Harbour and capsized near Steeple Rock. Of the 610 passengers and 123 crew on board, 53 people died.[1]

The wrecking of the Wahine is one of the better known maritime disasters in New Zealand's history, although there have been worse with far greater loss of life. New Zealand radio and television captured the drama as it happened, within a short distance of shore of the eastern suburbs of Wellington, and flew film overseas for world TV news.

Contents

The Wahine

The Wahine was an inter-island ferry designed and built specifically for the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand, and was one of many such ferries which together provided a widely-used transportation system connecting New Zealand's North and South Islands. Dating back to the turn of the Twentieth Century, on the two-way service for which the Wahine was operated, ferries plied the waters of the Cook Strait on a regular basis ferrying passengers and cargo back and forth between the two islands, making port at Wellington in the north and Lyttleton in the South.

The Wahine was built by Fairfields Ltd Shipbuilders in Glasgow, Scotland. The plan to build the ferry was called upon by the Union Steamship Company in 1961, and her keel was laid at Fairfields Shipyards on 14 September 1964 and was designated as Hull No. 830. Built of steel, her hull was completed in just ten months, and she was christened and launched by the Union Steamship Company's director's wife on 14 July 1965. Her machinery, cargo spaces and passenger accommodations were installed in the following months and she was completed in May 1966. She departed Greenock, Scotland for New Zealand on 18 June 1966 and arrived in Wellington on 24 July 1966, and sailed on her maiden voyage to Lyttleton one week later on 1 August.

The Wahine was 488 feet in length and 72 feet in width, and came to a total gross tonnage of 8,943.78 tons. Her twin turbo-alternator engines, fueled by four boilers and connected to twin propellers, gave the ship a top speed of 22 knots, or roughly 25.3 miles per hour.

Her safety features also were in compliance with all the standards upheld by maritime law at the time. Her hull was divided into fourteen watertight compartments divided by thirteen watertight bulkheads, designed so that if the hull were to be penetrated in any event such as a grounding or collision with another ship, the flooding of the hull could be confined to the damaged area. As seen with all passenger ships built since the Titanic disaster in 1912 in which 1,500 people lost their lives due to a lack of lifeboats, the Wahine was fully equipped with enough lifeboats and rafts for all passengers and crew. The Wahine carried eight large fiberglass lifeboats, two twenty-six foot motor lifeboats each with a capacity of 50 persons, and six larger thirty-one foot standard lifeboats each with a capacity of 99 persons. In addition, thirty-six inflatable rafts were stored in various locations around the ship. Each with a capacity of twenty-five persons, the two life-saving apparatus combined provided enough for all passengers and crew.

The Wahine was on an average crossing operated by a crew of 126. In the deck department, the Master, three officers, one radio operator and nineteen sailors managed the overall operation of the ship. In the engine department, eight engineers, two electricians, one donkeyman and twelve general workers supervised the operation of the engines. Finally, within the victualing department, sixty stewards, seven stewardesses, five cooks and four pursers catered to the needs of the passengers.

The passenger carrying capacity of the Wahine fluctuated between two settings. On trips between ports made during the day, the Wahine could carry 1,050 passengers, while on overnight crossings her passenger capacity fell to 924. On overnight crossings, passengers were quartered in a varied assortment of over three hundred single, two, three and four berth cabins, designed to cater to singles, married couples, families and larger traveling groups. In addition, two larger dormitory-style cabins were also aboard, each capable of housing twelve passengers. Common areas for passengers included a cafeteria, lounge, smoke room and gift shop, as well as access to both two enclosed promenades and the open decks.

Final crossing

On the evening of 9 April 1968, the Wahine departed Lyttleton for a routine overnight crossing to Wellington. She had aboard 610 passengers and 125 crew members.

Extreme weather conditions

In the early morning of 10 April, two violent storms merged over Wellington, creating a single extratropical cyclone storm that was the worst recorded in New Zealand's history. Cyclone Giselle was heading south after causing much damage in the north of the North Island. It hit Wellington at the same time as another storm which had driven up the West Coast of the South Island from Antarctica.[2] The winds in Wellington were the strongest ever recorded. At one point they reached a speed of 275 km/h and in one Wellington suburb alone ripped off the roofs of 98 houses. Three ambulances and a truck were blown onto their sides when they tried to go into the area to bring out injured people.

As the storms hit Wellington harbour, the Wahine was making her way past the Cook Strait on the last leg of her overnight journey to Wellington. At the time she had set out from Lyttleton, there had been no indication that the storms would be worse than those often experienced by vessels crossing the Cook Strait.[2]

Aground in Wellington Harbour

At 5:50 a.m., with winds gusting at between 130 and 150 km/h, Captain Hector Gordon Robertson decided to enter the harbour. Shortly afterwards, the storm exploded with great ferociousness over Wellington harbor, completely catching the Wahine by surprise. Twenty minutes later the winds had increased to 160 km/h, and the ship lost its radar. A huge wave pushed the Wahine off course and in line with Barrett Reef. The captain was unable to turn back on course, and decided to keep turning the ferry around and back out to sea again. For 30 minutes the Wahine battled into the waves and wind, but by 6:40 a.m. had lost control of her engines and had been driven onto the southern tip of Barrett Reef, near the harbor entrance less than one mile from shore. The Wahine drifted helplessly along the reef, shearing off her starboard propeller and gouging a large hole in her hull on the starboard side of the stern, beneath the waterline. Passengers were told that the ferry was aground, to put on their lifejackets and report to assembly points around the ship. The storm continued to grow more intense. As the winds increased to over 250km/h, the Wahine dragged its anchors and drifted into the harbour, close to the western shore. The weather was so bad that no help could be given from the harbour or the shore. At about 11.00 a.m. a harbour tug managed to reach the vessel, and tried to attach a line and tow the ferry, but the line gave way. Other attempts failed, but the deputy harbourmaster managed to climb aboard the Wahine from the pilot launch, which had also reached the scene.

Disaster unfolding

At about 1.15 p.m. the combined effect of the tide and the storm swung the Wahine around, providing a patch of clear water sheltered from the wind. As the ferry suddenly listed further and reached the point of no return, Captain Robertson gave the order to abandon ship. In a case similar to that seen in the sinking of the Andrea Doria twelve years earlier, the Wahine's severe starboard list left the four lifeboats on her port side useless. Only the four lifeboats on her starboard side could be launched.

The starboard motor lifeboat, Boat S1, capsized shortly after being launched. Those aboard were thrown into the water, and many of them drowned in the rough seas. Survivor Shirley Hick, remembered for having lost two of her three children in the Wahine disaster, recalled this event vividly as her three-year-old daughter Alma had drowned in this lifeboat. Some managed to hold onto the overturned boat as it drifted across the harbour to the eastern shore, towards Pencarrow Head. The three remaining standard lifeboats, which according to a number of survivors were terribly overcrowded, did manage to reach shore. Lifeboat S2 managed reach the rocky Seatoun Beach near Strathmore Park on the western side of the channel with roughly seventy passengers and crew, as did Lifeboat S4, which was terribly overcrowded with over one hundred people. The third lifeboat, a heavily overcrowded Boat S3, landed on the beach near the Wellington suburb of Eastbourne, about three miles away on the opposite side of the channel.[3](subscription required)

Due to the lack of lifeboats, hundreds of passengers and crew were forced into the rough waters as the Wahine sank. When the weather cleared, the sight of the Wahine foundering in the harbor urged many ships to race out of Wellington to the scene, including a number of tugs, fishing boats, yachts and small personal craft. These vessels managed to rescue hundreds of people. However, as the storm began to clear, a rather peculiar event occurred. Because of the angle at which Giselle struck the North Island, a vast amount of seawater was swept into Wellington harbor by the storm. When the storm began to calm, all that water began to pour out of the harbor and back into the ocean. With it, went hundreds of the Wahine's passengers and crew. Because of this, over 200 passengers and crew from the Wahine reached the rocky shore of the east side of the channel, south of Eastbourne. Because this area of Wellington Harbor was mostly desolate, unpopulated areas, many of the survivors were exposed to the elements for several hours while rescue teams tried to navigate the gravel road leading down the shoreline from Wellington. It was here where a number of bodies were recovered as well.[3]

At about 2.30 p.m. the Wahine rolled completely onto her side.

Some of the survivors reached the shore only to die of exhaustion or exposure. 51 people died at the time, and two others died later from injuries sustained in the shipwreck, 53 victims in all. Most of the victims were middle-aged or elderly, and also included three children, and died from drowning, exposure or injuries from being battered on the rocks. 46 people's bodies were found; 566 passengers were safe, as were 110 crew, and six were missing.

Aftermath

Investigation

Ten weeks after the shipwrecking, a Court of Inquiry found errors of judgement had been made, but stressed that the conditions at the time had been difficult and dangerous. Free surface effect caused the ferry to finally capsize due to a build-up of water on the vehicle deck, although several specialist advisers to the Inquiry believed that the ship had grounded a second time causing it to take on more water below decks. The report of the inquiry stated that more lives would almost certainly have been lost if the order to abandon ship had been given earlier or later. The storm was so strong that rescue craft would not have been able to safely help the passengers any earlier than about midday.[citation needed] Charges were brought against the ship's officers but all were acquitted.

Early hopes that the ship could be salvaged were eventually abandoned when the magnitude of structural damage became clear. As the wreck was a navigational hazard in Wellington Harbour, preparations were made over the following year to refloat the ship to allow it to be towed into Cook Strait for scuttling. However a nearly identical storm in 1969 broke up the wreck, and it was finally dismantled (partly by the Hikitia floating crane) where it lay.

Memorials

Today the Wahine Memorial Park marks the disaster, near where the survivors reached the shore at Seatoun. This park has a memorial plaque, the ship's anchor and chain, and replica ventilation pipes. A further plaque has also been placed on a rock at the parking area next to Burdans Gate on the eastern side of the harbour, marking the coast where many of the survivors and dead washed up. The Wahine's fore-mast is part of another memorial in Frank Kitts Park in central Wellington. Another mast is located on the Eastern Shore of Wellington Harbour where passengers were washed ashore. The Museum of Wellington City & Sea has a permanent commemorative exhibition on their maritime floor that includes artifacts from the ship and a film about the storm and the sinking.

References

- ^ Initially the official toll was 51, but two names were added 22 and 40 years later respectively. Kerry Williamson (9 April 2008). "Recognition 53rd Wahine victim". The Dominion Post. http://www.stuff.co.nz/stuff/4470696a11.html. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ a b Wahine Shipwreck (from the Christchurch Library website. Accessed 2008-06-07.)

- ^ a b "Questions and Answers". The Wahine. http://www.thewahine.co.nz/Questions.html. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

Further reading

- Emmanuel Makarios The Wahine Disaster: a tragedy remembered (2003, Grantham House; Wellington, N.Z.) ISBN 1869340795

- Max Lambert and Jim Hartley The Wahine Disaster (1969, Reed) & (1974, Collins Fontana Silver Fern)

- Kevin Boon The Wahine Disaster (1990, Nelson Price Milburn; Petone, N.Z.) ISBN 0-7055-1478-1 & (1999, Kotuku) (booklet, juvenile)

- T.E.V Wahine (O.N. 317814) Shipping casualty 10 April 1968 Report of Court and Annex Thereto, November 1968. This is the official report of the Court of Inquiry. It is extremely detailed and recommended for those who wish to do serious research into the disaster.

- C.W.N. Ingram New Zealand shipwrecks: 195 years of disaster at sea (Beckett, 1990; Auckland, N.Z.) ISBN 0-908676-49-2. This is the latest edition of a book first published in 1936. Arranged chronologically, the section on the Wahine gives an excellent hour-by-hour account of how the sinking happened as well as details of the Court of Inquiry which followed the disaster.

External links

- The Wahine disaster NZHistory.net.nz - includes images, sound and video

- The Wahine Murray Robinson's information-packed personal site detailing the ship's last hours, its history of operation, and the captain's career.

- The New Zealand Maritime Record: TEV Wahine Web Site is a detailed account of the ship, including the sinking, with many photographs.

- The Wahine Disaster by Max Lambert (1970)

- Co-ordinating the rescue - Wahine Disaster - explores the ability of the police to respond to the Wahine disaster

- Deaths from the sinking of the T.E.V. Wahine lists those who perished in the disaster.

- The Wahine Disaster gives a good account of the sinking, with links to Hurricane Giselle and other New Zealand disasters.

- Revell & Gorman-The Wahine storm is a research paper published in the New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. This paper (available in pdf format) is an academic evaluation of the meteorology of Hurricane Giselle.

- The day the Wahine went down, from the Wairarapa Times Age, NZ

- On This Day BBC story on Wahine

- Trailer to 2008 Wahine Disaster Film

- Dominion Post photos of Wahine: enter, go to Categories:Archive;Wahine

- TVNZ DVD of Television documentary

Categories:- Ferries of New Zealand

- History of the Wellington Region

- Shipwrecks of New Zealand

- 1968 in New Zealand

- Maritime incidents in 1968

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.