- Chester Roman Amphitheatre

-

Coordinates: 53°11′21″N 2°53′13″W / 53.1892°N 2.8870°W

Chester Amphitheatre is a Roman amphitheatre in Chester, Cheshire. The site is managed by English Heritage; it has been designated as a Grade I listed building,[1] and a scheduled monument.[2][3] The ruins currently exposed are those of a large stone amphitheatre, similar to those found in Continental Europe, although a smaller wooden amphitheatre may have existed on the site beforehand. Today, only the northern half of the structure is exposed; the southern half is covered by buildings, some of which are themselves listed.[4]

The amphitheatre is the largest so far uncovered in Britain, and dates from the 1st century, when the Roman fort of Deva Victrix was founded. The amphitheatre would have been primarily for military training and drill, but would also have been used for cock fighting, bull baiting and combat sports, including classical boxing, wrestling and gladiatorial combat.[4] In use through much of the Roman occupation of Britain, the amphitheatre fell into disuse around the year 350. The amphitheatre was only rediscovered in 1929, when one of the pit walls was discovered during construction work. Between 2007 and 2009, excavation of the amphitheatre is taking place for Chester City Council and English Heritage.[5]

Contents

Construction

The first amphitheatre is believed to have been a simple structure built by Legio II Adiutrix during their brief posting in Chester at some point in the late 70s, but was soon rebuilt by Legio XX Valeria Victrix when Legio II Adiutrix were reposted to the Danube region in 86. This amphitheatre fell into disuse when Legio XX were assigned to the construction of Hadrian's Wall, and upon their return around 275, the amphitheatre was once again rebuilt.[4]

The newer structure consisted of a 40 feet (12 m) high stone ellipse, 320 feet (98 m) along the major axis by 286 feet (87 m) along the minor. The major axis lines up approximately along the north-south line, and exits are placed at all four points of the compass; in keeping with most Roman forts of the era, the amphitheatre was placed at the south east corner of the fort. The amphitheatre could easily seat 8,000 people, and around it, a sprawling complex of dungeons, stables and food stands were built to support the contests, while a shrine to Nemesis, goddess of retribution, was built at the north entrance to the arena. The unusually large and developed amphitheatre complex has led historians to speculate that Chester would have become capital of Roman Britain had the Romans successfully captured Ireland.[6][7]

Dereliction

Following the Roman departure from Britain, the amphitheatre once again fell derelict, and the masonry was scavenged from the site leaving only a small depression at the centre of the site, which was used to stage bear fights and public executions, and was eventually completely filled in by erosion and refuse dumping. A Victorian convent and manor house complex known as "Dee House" were built over the south end of the arena, while a Georgian townhouse called "St. John's House" was built over the north end. Although all records of the amphitheatre were lost, the unfavourable contours of the filled-in amphitheatre prevented roads from passing through the site, preserving the underground remains and allowing the site to later be excavated without the need for extensive demolition.[4]

Rediscovery

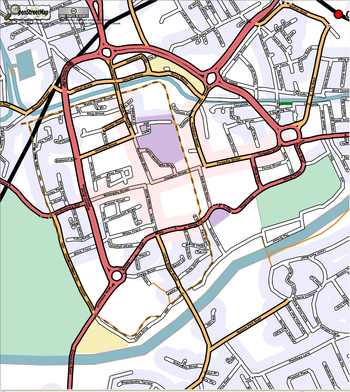

The location of the amphitheatre within Chester, showing the curved road that surrounds the perimeter. Although the existence of an amphitheatre in Chester had been speculated for years, the first evidence for it was discovered in 1929 when gardening works at Dee House revealed a long curved wall. Further works revealed that the structure was largely intact underneath the ground. However, the site of the amphitheatre was covered by buildings and lay in the way of a new planned road, designed to bypass the narrow curved lane which skirted the perimeter.[4]

Nevertheless, the Chester Archaeological Society agreed to raise enough money to divert the new road and excavate the arena. Progress was initially slow; the council refused to change the course of the road unless money was raised to fund the substantial demolition work that would be required, and it was not until 1933 that the route of the road was finally changed. In order to fund the excavations, Chester Archaeological Society purchased St. John's House and leased it to the council to fund the dig. The dig was initially scheduled for 1939, but was postponed indefinitely with the outbreak of World War II.[4]

Work resumed in 1957, when the council vacated St. John's House and the Ministry of Works offered a substantial subsidy for excavation. As Dee House was still in use, only the northern half could be excavated. A small area was dug up, and the rest redeveloped as a short-lived park, which was quickly removed to allow further excavation. The badly pillaged and damaged supporting walls were removed and marked with concrete trim and the arena wall was propped up with concrete panels.

The amphitheatre remained in this state until 2000, when archaeological work was resumed on the site. Among the finds were the remains of the earlier amphitheatres and of an even older Roman building existing on the site. A number of cooked animal bones and cheaply made Roman pots showing images of gladiator combat were also found, leading a number of historians to suggest that the site was one of the first places to develop souvenirs for spectators to buy.[8]

The amphitheatre's central, river-side location is very valuable. Cheshire County Council purchased an area to the south of the exposed area for Chester's new County Court, the northern wing and car park of which were built over the south western corner of the arena. Despite the council's insistence that the court cover as little of the arena as possible, the work was widely unpopular with residents and the press, especially following the Council's previous support of excavation projects.[9] As of 2007, the southern half of the amphitheatre remains covered by Dee House and the County Court.

Following further discoveries at the site in 2010, some writers suggested that the amphitheatre was the prototype for King Arthur's Round Table,[10] but English Heritage, acting as consultants to a History Channel documentary in which the claim was made, declared that there was no archaeological basis to the story.[11]

Amphitheatre mural

A trompe l'oeil mural was commissioned in August 2010 by Chester Renaissance to enable visitors to experience the illusion of a complete amphitheatre as well as showing how the original structure may have looked. Archeologists advised internationally renowned artist Gary Drostle on the original construction and found artifacts from the site.

The artist designed an image that spanned the 50 metre walkway wall, starting with a continuation of the current amphitheatre edges that merged seamlessly into the recreation of the original walls and seating towards the centre. The painted ellipsis of the sand covered ground and depiction of the central tethering stone allow a viewer to experience a full immersion in the amphitheatre that was not possible with the previous, blank wall. Details such as the red, marble covered arena wall, position of the doorways and vomitoriums and outside walls were all carefully recreated as the evidence suggested.

Taking over 6 weeks to complete with two, six metre scaffolding towers and five painters, the public and tourist groups could watch the progression of the mural and interact with the artist and his assistants, the British weather dictating working hours.

The mural will be a permanent feature of the amphitheatre. The artist used Keim Mineral Paints, invented in 1878. The system is a liquid silicate paint which comprises a potassium silicate binder with inorganic fillers (feldspar) and natural earth oxide colour pigments. When applied onto a mineral substrate the binder is absorbed and forms a micro-crystalline silicate structure. This crystalline structure allows the substrate to breathe but prevents the ingress of driven rain.[12]

See also

List of Scheduled Monuments in Cheshire dated to before 1066

References

- ^ "Remains of Roman amphitheatre", The National Heritage List for England (English Heritage), 2011, http://list.english-heritage.org.uk/resultsingle.aspx?uid=1375863, retrieved 28 April 2011

- ^ Pastscape: Roman Amphitheatre, English Heritage, http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=69224, retrieved 31 March 2009

- ^ "Roman amphitheatre (southern part)", The National Heritage List for England (English Heritage), 2011, http://list.english-heritage.org.uk/resultsingle.aspx?uid=1004638, retrieved 28 April 2011

- ^ a b c d e f The Chester Amphitheatre, B&W Pics, http://www.chesterwalls.info/amphitheatre.html, retrieved 30 July 2007

- ^ Amphitheatre project, Chester.gov.uk, http://www.chester.gov.uk/council_and_democracy/news_and_views/projects_in_the_news/amphitheatre_project.aspx Retrieved on 16 April 2008.

- ^ Spicer, Graham (9 January 2007), Revealed - new discoveries at Chester's Roman Amphitheatre, Culture24, http://www.culture24.org.uk/history+%2526+heritage/time/roman/art42592, retrieved 27 November 2009

- ^ "Britain's Lost Colosseum". Timewatch. BBC. BBC Two. 20 May 2005.

- ^ Fleming, Nic (18 March 2005), They came, they saw, they bought the souvenir, Daily Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2005/05/18/nampi18.xml&sSheet=/news/2005/05/18/ixnewstop.html, retrieved 30 July 2007

- ^ The Chester Amphitheatre 2, B&W Pics, http://www.chesterwalls.info/amphitheatre2.html, retrieved 30 July 2007

- ^ Evans, Martin (11 July 2010), "Historians locate King Arthur's Round Table", Daily Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/7883874/Historians-locate-King-Arthurs-Round-Table.html, retrieved 15 July 2010

- ^ Pitts, Mike (November 2010), "Britain in Archaeology", British Archaeology (York, England: Council for British Archaeology) (115): 8, ISSN 1357-4442, "The claims...have no basis whatever in the archaeological evidence"

- ^ About Us, Keim Mineral Paints, http://www.keimpaints.co.uk/about/, retrieved 19 February 2011

External links

Media related to Roman amphitheatre, Chester at Wikimedia CommonsCategories:

Media related to Roman amphitheatre, Chester at Wikimedia CommonsCategories:- 1st-century architecture

- English Heritage sites in Cheshire

- Roman sites in Cheshire

- Archaeological sites in Cheshire

- Grade I listed buildings in Cheshire

- Ruins in Cheshire

- Roman amphitheatres in the United Kingdom

- History of Chester

- Scheduled Ancient Monuments in Cheshire

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.