- Tiger Quoll

-

Tiger Quoll[1]

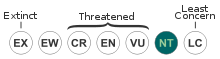

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Infraclass: Marsupialia Order: Dasyuromorphia Family: Dasyuridae Genus: Dasyurus Species: D. maculatus Binomial name Dasyurus maculatus

Kerr, 1792Subspecies - D. m. maculatus

- D. m. gracilis

Range of the Tiger Quoll: The tiger quoll (Dasyurus maculatus), also known as the spotted-tail quoll, the spotted quoll, the spotted-tailed dasyure or (erroneously) the tiger cat, is a carnivorous marsupial native to Australia. It is mainland Australia's largest, and the world's longest (the biggest is the Tasmanian Devil), living carnivorous marsupial and it is considered an apex predator.

Contents

Taxonomy

The tiger quoll is a member of the family Dasyuridae, which includes most carnivorous marsupial mammals. This quoll was first described in 1792 by Robert Kerr, the Scottish writer and naturalist, who placed it in the genus Didelphis, which includes several species of American opossum. The species name, maculatus, indicates that this species is spotted.[3]

Two subspecies are recognised:[3]

- D. m. maculatus, found from southern Queensland south to Tasmania

- D. m. gracilis, found in an isolated population in northeastern Queensland, where it is classified as endangered by the Department of Environment and Heritage

Description

The tiger quoll is the largest of the quolls. Males and females of D. m. maculatus weigh on average 3.5 kg and 1.8 kg respectively and males and females of D. m. gracilis weigh on average 1.6 and 1.15 respectively.[4] The next largest species, the western quoll, weighs on average 1.31 kg for males and 0.89 kg for females.[5] The tiger quoll has relatively short legs but has a tail as long as its body and head combined.[4] Both its head and neck are stout and its snout is slightly rounded. The skull is broad and flat with an only slightly rounded profile and with a slender rostrum that is parallel between canines and molar teeth, a trait not found other quoll species.[4] It has 5 toes on each feet, both front and hind, and the hind feet have well developed halluxes. The wrist and heel joints are covered foot pads that pinked and ridged, owing to its arboreal lifestyle.[6] This makes up for the fact that its tail is not prehensile. The tiger quoll has a reddish-brown pelage with white spots and colourations do not change seasonally. It is the only quoll species with spots on its tail in addition to its body. An orange-brown coloured oil covers both its fur and skin. The underside can be grayish or creamy white. The average length of D. m. maculatus is 930 mm for males and 811 for females respectively. For D. m. gracilis, the average length of males and females respectively is 801 mm and 742 mm.[4]

Range and ecology

The tiger quoll is found in eastern Australia in the area that receives more than 600 mm of rainfall per year.[7][8] It was once widely distributed from southeastern Queensland, though eastern New South Wales, Victoria, southeastern South Australia and Tasmania. Since European settlement of Australia, the mainland range has reduced by 50-90% and populations there are now fragmented.[9] Tiger quolls are rare southeastern Queensland were its range is fragmented and contracting.[10] In Victoria and New South Wales, tiger quolls occur from the coast to the snowline, above 1,500 m in elevations, and inland to the western plains along the Murray River.[7] Their populations have halved and are currently disjunct in Victoria.[8] Apparently, the range decline in New South Wales is lower than in Victoria but they are still rare, especially in the south.[8] It is largely rare or extirpated were it was probably never common. In Tasmania, the tiger quoll is recorded most frequently in the north and west of the island correlating with seasonally reliable rainfall, from sea level to ca. 1,000 m and less commonly from the drier, more climatically variable eastern parts.[11] Tiger quolls were once native to Flinders and King Islands but were extirpated since the 20th century and they are now absent from all Tasmanian offshore islands.[12]

Tiger quolls live in a variety of habitats, such as wet scrub and coastal heartland, but they are most common in wet forest types such as rainforests and closed eucalypt forest. [6][11] Tiger quolls are moderately arboreal.[13] They can move up to 200 linear meters on log and around 11% of the distances they travel is above ground.[6] Quolls eat a variety of prey species, including insects, crayfish, lizards, snakes, birds, domestic poultry, small mammals, platypus, rabbits, arboreal possums, macropods and wombats.[4] They have been recorded killing pademelons and small wallabies while larger animals, such as kangaroos, feral pigs, cattle and dingoes are likely scavenged.[4][13] Adult males eat larger prey than females and both eat larger prey than subadults.[4] The tiger quoll scavenges less frequently than the eastern quoll and the Tasmanian devil, although it is a common scavenger at roadkills, campsites and houses.[6] A high proportion of the quoll’s diet is arboreal.[13] They are adept at climbing high into trees and can capture possums and sleeping birds at night.[6] The flexibility of their diet suggests that their prey base is not detrimentally affected by bushfires.[14] When hunting, quolls stalk their prey, walking or running forward when the prey has its head down and stopping when its head is raised.[4] The quoll will pounce and leap on their prey and will bite at the base of the skull or top of the neck, depends on the size of the victims.[6] Small prey is pinned with the forepaws and killed. With large prey, the quoll will leap on its back and grips with all four legs while biting the neck.[4] Quolls themselves may be preyed on by Tasmanian devils and masked owls in Tasmania and dingos and dogs in mainland Australia.[4] It may also be preyed on by wedge-tailed eagles and large pythons. Tiger quolls avoid encounters with adult devils but will chase subadults away from carcasses. A adult quoll and a subadult devil both have been recorded with severe injuries after a fight and it is probable that the quoll died.[6] It is also possible that quolls compete with introduced carnivores like foxes, cats and wild dogs. Tiger quolls can be hosts for at least 23 species of endoparasites including five flukes, four tapeworms, 14 nematodes and one protozoan.[4]

Life history

Tiger quolls are generally nocturnal although juveniles and females with young in the den, are frequently active during the day and commonly emerge and return to their dens in daylight.[13][7][10] Quolls rest during the day in dens which may be underground burrows, caves, rock crevices, tree hollows, hollow logs, under house or in sheds.[7][6][10] They move both by walking and by making a bounding gait.[4] Quolls do not use trails extensively, although they may use runways and roads for foraging and scent marking. Tiger quolls may live in home ranges that range 580-875 ha for males and 90-188 for females.[4] Female tend to have loner residencies than males, although in one population study, 50% of both sexes were transients.[13] The home ranges of males can overlap, but each male has an exclusive core area of at least 128 ha.[10] The home ranges of females may overlap less.[13] Quoll sometimes share dens during the breeding season.[10] Females tend to be aggressive towards males after mating and this intensifies as birth approaches. For the tiger quoll, olfactory and auditory signals are more important than visual signals in communication. When greeting each other, quolls will sniff each other nose to nose and males will sniff the rumps of estrus females.[4] Quolls also engage in face washing which involves mouth and ear secretions being smeared on the head and besides cleaning this may serve as self-marking behavior.[15] Some populations have communal latrines while others don’t. Latrines are usually located in rocky creek beds, cliff bases and on roads.[13] Cloacal dragging often accompanies defecation.[13]

Tiger quolls are generally not vocal, however vocalizations are given in all social interactions, including agonistic, mating and maternal care.[16] Quolls will emit guttural huffs, coughs, hisses and piercing screams when in agonistic encounter with each other or when disturbed by humans.[4] Females in estrus will make soft "cp-cp-cp" sounds that are only heard at this time. [16] Females and their young will call to each other with muffled strings of "chh-chh" made by females and "echh-echh" made by young. Juveniles vocalize frequently when fighting and their mother will hiss when they clamber over her.[4] During agonistic encounters, quolls use open-mouth behavioral threats in addition to the above mentioned vocalizations. The mouth is opened wide, displaying their teeth to the opponent; ears are laid back; and the eyes are narrowed. During fights, males grasp each other with their forepaws, kick with their hind feet, bite and screech.[6]

Tiger quolls are seasonal breeders. They mate in midwinter (June/July), although females, which enter estrus three days at a time, may do so as early as April.[17] Vaginal smear indicate a ca. 21 day cycle.[16] The mating behavior of the tiger quoll is unique among the quoll species in involving vocalizations of the female and her readily accepting the male’s mounting attempts.[4] When encountering a mate, a respective female will move about slowly, pausing, occasionally with head lowered and rump raised. The male follows the female, sniffs her cloacal region and makes staccato cries. The female’s "cp-cp-cp" vocalization causes the male to tone down his own vocalizations.[4] During copulation, the male grasps the female’s body with his forearms and will often palpate her abdomen and stroke her sides. The male holds the back of the female’s neck during copulation but will sometimes release his bite to lick the female’s neck. Among dasyurids, both behaviors are unique to this species.[16] Though copulation, females crouches with her head lowered and eyes half-closed.[16] She will also vocalize frequently. Copulation is prolonged and last from several hours to 24 hours. Females develop a swollen neck region during estrus. During parturition, a female quoll stands quiety for about 1.5 hours with the hindquarters raised and the tail curled beside her.[4] For the first three weeks of pouch life, females elevate their hindquarters as they walk. Females with pouch young rest on their sides or crouch with their hind legs raised so that no pressure is on the pouch. Females will build nests and spend long periods of time in them when the young permanently leave the pouch.[4] For their first 50-60 days of life, before their eyes open, the young locate siblings and their mother by calling, moving around the nest and by curling nest to warm objects. By 70 days, the eyes are open and the young cease these behaviors. A mother does not carry her young on her back but she does tolerate them climbing on her while in the nest[16] or when they cling to her back with their teeth and claws when they get frightened. Social play among the young is well developed by 90 days.[4] As the young grow, they stray further from their mothers and after 100 days the female spends progressively less time with her young and become more aggressive towards them.[18]

Conservation status

The tiger quoll is listed by the IUCN on the Red List of Threatened Species with the status "near threatened".[2] The Australian Department of the Environment and Heritage considers the northern subspecies D. m. gracilis as endangered. This species is vulnerable to decline for a number of reasons. It is a climatic and habitat specialis, it occurs in naturally low population densities, is subject to competition for native and introduced carnivores, has large space requirements, a short lifespan and low lifetime fecundity.[4] Fragmentation and loss of habitat are major threats as these can affect prey availability, hunting ability and increase contact with humans.[4] Mortality factors that are directly caused by humans include persecution by farmers, motor vehicles and 1080 poisoning from baits. Recovery objectives[19] that are used for the tiger quoll include: monitor populations; preventing further habitat loss and fragmentation; minimizing impacts that 1080 baiting may have; undertaking public education, especially of rural private land holders, to reduce direct killing.

References

- ^ Groves, C. (2005). Wilson, D. E., & Reeder, D. M, eds. ed. Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 25. OCLC 62265494. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3.

- ^ a b Burnett, S. & Dickman, C. (2008). Dasyurus maculatus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 28 December 2008. Database entry includes justification for why this species is listed as near threatened

- ^ a b Edgar, R.; Belcher, C. (1995). "Spotted-tailed Quoll". In Strahan, Ronald. The Mammals of Australia. Reed Books. pp. 67–69

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Jones M. E., Rose R. K., Burnett S., (2001) "Dasyurus maculates", Mammalian Species 676:1-9.

- ^ Serena M., Soderquist T., (1995) "Western quoll". Pp. 62-64. In: The mammals of Australia. Second edition (R. Strahan, ed). Australian Museum/Reed Books, Sydney, New South Wales.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jones M. E., (1995) Guild structure of the large carnivores in Tasmania. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia.

- ^ a b c d Edgar R., Belcher C., (1995) "Spotted-tailed quoll". Pp. 67-69. In: The mammals of Australia. Second edition (R. Strahan, ed). Australian Museum/Reed Books, Sydney, New South Wales.

- ^ a b c Mansergh I. (1984) "The status, distribution and abundance of Dasyurus maculates (tiger quoll) in Australia, with particular reference to Victoria". Australian Zoologist 21:109-22.

- ^ Maxwell S., A. A. Burbidge, K. Morris. (1996) The action plan for Australian marsupials and monotremes. Report for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Species Survival Commission Australasian Marsupial and Monotreme Specialist Group.

- ^ a b c d e Watt A. (1993) Conservation status and draft management plan for Dasyurus maculates and D. hallucatus in southern Queensland. Report for Queenland Department of Environment and Heritage and The Department of the Environment, Sport and Territories, October: 1-132.

- ^ a b Jones M. E., R. K Rose (1996) Preliminary assessment of distribution and habitat association of the spotted-tailed quoll (Dasyurus maculates maculatus) and eastern quoll (D. viverrinus) in Tasmania to determine conservation and reservation status. Nature Conservation Branch, Parks and Wildlife Service. Report to the Tasmanian Regional Forest Agreement Environment and Heritage Technical Committee, November:1-68.

- ^ Hope J. H. (1972) "Mammals of the Bass Strait islands". Proceeding of the Royal Society of Victoria 85:163-96.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Burnett S. (2000) The ecology and endangerment of spotted-tailed quoll, Dasyurus maculates. Ph.D. dissertation, James Cook Univeristy of North Queensland, Townville, Australia.

- ^ Dawson, J. P.; Claridge, A. W.; Triggs, B.; Paull, D. J. (2007). "Diet of a native carnivore, the spotted-tailed quoll (Dasyurus maculatus), before and after an intense wildfire". Wildlife Research 34 (5): 342. doi:10.1071/WR05101.

- ^ Eisnberg J. F., I. Golani. (1977) "Communication in metatheria". Pp. 575-99. In: How animals communicate. (T. A. Sebeok, ed). Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

- ^ a b c d e f Settle G. A. (1978) The quiddity of tiger quoll. Australian Journal of Zoology 9:164-69.

- ^ Edgar R., Belcher C., (1983) "Spotted-tailed quoll". Pp. 18-19. In: The mammals of Australia. First edition (R. Strahan, ed). Australian Museum/Reed Books, Sydney, New South Wales.

- ^ Collins L., Conway K. (1986) "A quoll by any other name". Zoogoer. January-February:14-16.

- ^ Maxwell, S., Burbidge, A. A. and Morris, K. (1996) The 1996 Action Plan for Australian Marsupials and Monotremes. Australasian Marsupial and Monotreme Specialist Group, IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland, Switzerland.

External links

- Description from the University of Michigan

- Another description from Australia.

- Australian Web Site

- Spotted Quoll entry in the IUCN Red List.

- Another photo of a Tiger Quoll

- Action Plan for Australian Marsupials and Monotremes.

Categories:- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Carnivorous marsupials

- Dasyuromorphs

- Extinct mammals of South Australia

- Vulnerable fauna of Australia

- Mammals of Tasmania

- Mammals of Queensland

- Mammals of New South Wales

- Mammals of Victoria (Australia)

- Marsupials of Australia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.