- Mexican Cession

-

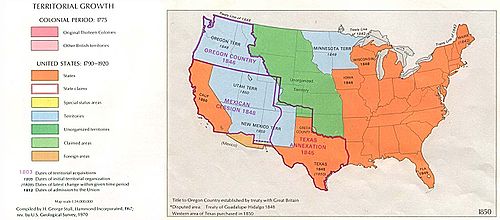

The Mexican Cession of 1848 is a historical name in the United States for the region of the present day southwestern United States that Mexico ceded to the U.S. in 1848, excluding the areas east of the Rio Grande, which had been claimed by the Republic of Texas, though the Texas Annexation resolution two years earlier had not specified Texas's southern and western boundary.

Mexico controlled the territory from 1821, the year it achieved independence from Spain until 1848, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War, a total of twenty-seven years, excluding the territory of the Republic of Texas, which became independent in 1836, which was only under the control of the Mexican government for fifteen years. The United States of America had taken actual control of the Mexican territories of Santa Fe de Nuevo México and Alta California in 1846 early in the War.

Contents

Background

The cession of this territory from Mexico was a major goal of the war.[citation needed] California and New Mexico were captured soon after the start of the war and the last resistance there was subdued in January 1847, but Mexico would not accept the loss of territory. Therefore during 1847 United States troops invaded central Mexico and occupied the Mexican capital of Mexico City, but still no Mexican government was willing to ratify transfer of the northern territories to the U.S. It was uncertain whether any treaty could be reached. There was even an All of Mexico Movement proposing complete annexation of Mexico among Eastern Democrats, opposed by Southerners like John Calhoun who wanted additional territory for white Southerners and their black slaves but not the large population of central Mexico. Eventually Nicholas Trist negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceding only California and New Mexico in early 1848 after President Polk had already attempted to recall him from Mexico as a failure. The U.S. Senate approved the treaty, rejecting amendments from Jefferson Davis to also annex most of northeastern Mexico and by Daniel Webster to not even take California and New Mexico.[1]

The United States also paid $15,000,000 ($298,310,309 in 2005 dollars) for the land, and agreed to assume $3.25 million in debts to US citizens.[2] The land ceded by Mexico is 14.9% of the total area of the current United States territory. 1.36 million km² (the Mexican Cession was 525,000 square miles (1,400,000 km2) and, if the other lands lost in Texas, Colorado, eastern New Mexico, Kansas and Oklahoma are included, 225,000 square miles (580,000 km2), Mexico lost 55% of its pre-war territory).[3] While technically the territory was purchased by the United States, the $15 million payment was simply credited against Mexico's enormous debt towards the U.S. at that time.

As of July 1, 2007, the states of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico had a total population of 50,072,597 out of 305,986,357 nationwide, or 16.4% of the US population.

For the fifteen years between 1821, when Mexican independence was secured and the Texas Revolution in 1836, the Mexican Cession had formed approximately 42% of the country of Mexico; prior to that, it had been a part of the Spanish colony of New Spain for some three centuries. Beginning in the early seventeenth century, a chain of Spanish missions and settlements extended into the New Mexico region, mostly following the course of the Rio Grande from the El Paso area to Santa Fe.

Subsequent organization and the North-South conflict

Soon after the war started and long before negotiation of the new US-Mexico border, the question of slavery in the territories to be acquired polarized the Northern and Southern United States in the bitterest sectional conflict up to this time, which lasted for a deadlock of four years during which the Second Party System broke up, Mormon pioneers settled Utah, the California Gold Rush settled California, and New Mexico under a federal military government turned back Texas's attempt to assert control over territory Texas claimed as far west as the Rio Grande. Eventually the Compromise of 1850 preserved the Union, but only for another decade. Proposals included:

- The Wilmot Proviso, which was created by Republican Party Senator David Wilmot, banning slavery in any new territory to be acquired from Mexico, not including Texas which had been annexed the previous year. Passed by the United States House of Representatives in August 1846 and February 1847 but not the Senate. Later an effort to attach the proviso to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo also failed.

- Failed amendments to the Wilmot Proviso by William W. Wick and then Stephen Douglas extending the Missouri Compromise line (36°30' parallel north) west to the Pacific, allowing slavery in most of present day New Mexico and Arizona, Las Vegas, Nevada, and Southern California, as well as any other territories that might be acquired from Mexico. The line was again proposed by the Nashville Convention of June 1850.

- Popular sovereignty, developed by Lewis Cass and Douglas as the eventual Democratic Party position, letting each territory decide whether to allow slavery.

- William L. Yancey's "Alabama Platform," endorsed by the Alabama and Georgia legislatures and by Democratic state conventions in Florida and Virginia, called for no restrictions on slavery in the territories either by the federal government or by territorial governments before statehood, opposition to any candidates supporting either the Wilmot Proviso or popular sovereignty, and federal legislation overruling Mexican anti-slavery laws.

- General Zachary Taylor, who became the Whig candidate in 1848 and then President from March 1849 to July 1850, proposed after becoming President that the entire area become two free states, called California and New Mexico but much larger than the eventual ones. None of the area would be left as an unorganized or organized territory, avoiding the question of slavery in the territories.

- The Mormons' proposal for a State of Deseret incorporating most of the area of the Mexican Cession but excluding the largest non-Mormon populations in Northern California and central New Mexico was considered unlikely to succeed in Congress, but nevertheless in 1849 President Taylor sent his agent John Wilson westward with a proposal to combine California and Deseret as a single state, decreasing the number of new free states and the erosion of Southern parity in the Senate.

- Senator Thomas Hart Benton in December 1849 or January 1850: Texas's western and northern boundaries would be the 102nd meridian west and 34th parallel north.

- Senator John Bell (with assent of Texas) in February 1850: New Mexico would get all Texas land north of the 34th parallel north (including today's Texas Panhandle), and the area to the south (including the southeastern part of today's New Mexico) would be divided at the Colorado River (Texas) into two Southern states, balancing the admission of California and New Mexico as free states.[4]

- First draft of the compromise of 1850: Texas's northwestern boundary would be a straight diagonal line from the Rio Grande 20 miles (30 km) north of El Paso to the Red River (Mississippi watershed) at the 100th meridian west (the southwestern corner of today's Oklahoma).

- The Compromise of 1850, proposed by Henry Clay in January 1850, guided to passage by Douglas over Northern Whig and Southern Democrat opposition, and enacted September 1850, admitted California as a free state including Southern California and organized Utah Territory and New Mexico Territory with slavery to be decided by popular sovereignty. Texas dropped its claim to the disputed northwestern areas in return for debt relief, and the areas were divided between the two new territories and unorganized territory. El Paso where Texas had successfully established county government was left in Texas. No southern territory dominated by Southerners (like the later short-lived Confederate Territory of Arizona) was created. Also, the slave trade was abolished in Washington, D.C. (but not slavery itself), and the Fugitive Slave Act was strengthened.

Gadsden Purchase

It quickly became apparent that the Mexican Cession did not include a feasible route for a transcontinental railroad connecting to a southern port. The topography of the New Mexico Territory included mountains that naturally directed any railroad extending from the southern Pacific coast northward, to Kansas City, St. Louis, or Chicago. Southerners, anxious for the business such a railroad would bring (and perhaps hoping to establish a slave-state beachhead on the Pacific coast[5]), agitated for the acquisition of additional, railroad-friendly land, thus bringing about the Gadsden Purchase.

References

- ^ George Lockhart Rives. The United States and Mexico, 1821-1848. pp. 634–636. http://books.google.com/books?id=vfhAAAAAIAAJ.

- ^ Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Articles XII-XV

- ^ Table 1.1 Acquisition of the Public Domain 1781-1867

- ^ google.com/books Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association, January 1904

- ^ Richards, The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War, p. 126 (2007).

Territorial expansion of the United States Concept: Manifest Destiny

Thirteen Colonies (1776) · Treaty of Paris (1783) · Louisiana Purchase (1803) · Red River Cession (1818) · Adams–Onís Treaty (1819) · Texas Annexation (1845) · Oregon Treaty (1846) · Mexican Cession (1848) · Gadsden Purchase (1853) · Guano Islands Act (1856) · Alaska Purchase (1867) · Annexation of Hawaii (1898) · Treaty of Paris (1898) · Treaty of the Danish West Indies (1917) Categories:

Categories:- History of United States expansionism

- Mexican–American War

- 1848 in Mexico

- 1848 in the United States

- Treaties involving territorial changes

- Territorial evolution

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.