- Cumacea

-

Cumacea

Temporal range: Mississippian–Recent

Iphinoe trispinosa Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Subphylum: Crustacea Class: Malacostraca Superorder: Peracarida Order: Cumacea

Krøyer, 1846 [1]Families 8 to 11, See taxonomy

Cumacea is an order of small marine crustaceans, occasionally called hooded shrimp. Their unique appearance and uniform body plan makes them easy to distinguish from other crustaceans.

Contents

Anatomy

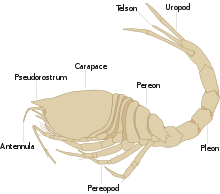

Cumaceans have a strongly enlarged carapace (head shield) and pereon (breast shield), a slim abdomen and a forked tail. The length of most species varies from 1 to 10 millimetres (0.04 to 0.39 in).

The carapace of a typical cumacean is composed of several fused dorsal head parts and the first three somites of the thorax. This carapace encloses the appendages that serve for respiration and feeding. In most species, there are two eyes at the front side of the head shield, often merged into a single eye lobe. The five posterior somites of the thorax form the pereon. The pleon (abdomen) consists of six cylindrical somites.

The first antenna (antennule) has two flagella, the outer flagellum usually being longer than the inner one. The second antenna is strongly reduced in females, and consists of numerous segments in males.

Cumaceans have six pairs of mouthparts: one pair of mandibles, one pair of maxillules, one pair of maxillae and three pairs of maxillipeds.[2][3]

Ecology

Cumaceans are mainly marine crustaceans. However, some species can survive in water with a lower salinity, like brackish water (e.g. estuaries). In the Caspian Sea they even reach some rivers that flow into it. Few species live in the intertidal zone.

Most species live only one year or less, and reproduce twice in their lifetime. Deepsea species have a slower metabolism and presumably live much longer.

Cumaceans feed mainly on microorganisms and organic material from the sediment. Species that live in the mud filter their food, while species that live in sand browse individual grains of sand. In the genus Campylaspis and a few related genera, the mandibles are transformed into piercing organs, which can be used for predation on forams and small crustaceans.[4]

Many shallow water species show a diurnal cycle, with males emerging from the sediment at night and swarming to the surface.[5]

Importance

Like Amphipoda, cumaceans are an important food source for many fishes. Therefore, they are an important part of the marine food chain. They can be found on all continents.

Reproduction and development

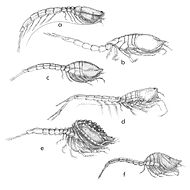

Cumaceans are a clear example of sexual dimorphism: males and females differ significantly in their appearance. Both sexes have different ornaments (setation, knobs, and ridges) on their carapace. Other differences are the length of the second antenna, the existence of pleopods in males, and the development of a marsupium in females. There are generally more females than males, and females are also larger than their male counterparts.

Cumaceans are epimorphic, which means that the number of body segments doesn't change during the different developmental stages. This is a form of incomplete metamorphosis. Females carry the embryos in their marsupium for some time. The larvae leave the marsupium during the so-called manca stage, in which they are almost fully grown and only miss their last pair of pereopods.

History of research

The order of Cumacea was already known since 1780, when Ivan Ivanovich Lepekhin described the species Oniscus scorpioides (later renamed to Diastylis scorpioides). During that time, many scientists thought that the cumaceans were some kind of larval stage of decapods. In 1846, they were recognized as a separate order by Henrik Nikolaj Krøyer. Twenty-five years later about fifty different species had been described, and currently there are more than 1,400 described species. The German zoologist Carl Wilhelm Erich Zimmer studied the order Cumacea very intensively.

Fossil record

The fossil record of cumaceans is very sparse, but extends back into the Mississippian age.[6]

Taxonomy

Cumaceans belong to the superorder Peracarida, within the class Malacostraca. The order Cumacea is subdivided into 8 to 11 families, about 139 genera, and 1593 species.[7] The families most marine zoologists recognize are:

- Bodotriidae Scott, 1901 (360 species)

- Ceratocumatidae Calman, 1905 (8 species)

- Diastylidae Bate, 1856 (281 species)

- Gynodiastylidae Stebbing, 1912 (103 species)

- Lampropidae Sars, 1878 (90 species)

- Leuconidae Sars, 1878 (121 species)

- Nannastacidae Bate, 1866 (350 species)

- Pseudocumatidae Sars, 1878 (29 species)

See also

References

- ^ H. N. Krøyer (1846). "On Cumaceerne Familie". Naturh. Tidsskr. 2 (2): 123–211, plates 1–2.

- ^ N. S. Jones (1976). British Cumaceans. Synopses of the British Fauna No. 7. Academic Press. ISBN 9780123893505.

- ^ R. Brusca & G. Brusca (2003). Invertebrates (2nd ed.). Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 9780878930975.

- ^ M. Bacescu & I. Petrescu (1999). "Traité de zoologie. Crustacés Peracarides. 10 (3 A). Ordre des Cumacés". Mémoires de l'Institut Océanographique de Monaco 19: 391–428.

- ^ T. Akiyama & M. Yamamoto (2004). "Life history of Nippoleucon hinumensis (Crustacea: Cumacea: Leuconidae) in Seto Inland Sea of Japan. I. Summer diapause and molt cycle" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series 284: 211–225. doi:10.3354/meps284211. http://www.int-res.com/articles/meps2004/284/m284p211.pdf.

- ^ Frederick R. Schram, Cees H. J. Hof, Royal H. Mapes & Polly Snowdon (2003). "Paleozoic cumaceans (Crustacea, Malacostraca, Peracarida) from North America". Contributions to Zoology 72 (1): 1–16. http://dpc.uba.uva.nl/ctz/vol72/nr01/art01.

- ^ G. Anderson (2010). "Cumacea Classification" (PDF). Peracarida Taxa and Literature. University of Southern Mississippi. http://peracarida.usm.edu/CumaceaTaxa.pdf. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

External links

Categories:- Cumacea

- Crustaceans

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.