- Notre-Dame de la Garde

-

Notre-Dame de la Garde

Notre-Dame de la Garde, seen from the Vieux Port

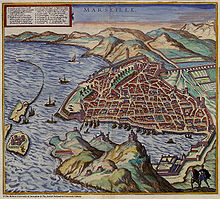

Basic information Affiliation Roman catholic District Archdiocese of Marseilles Architectural description Architectural type Minor basilica Architectural style Neo-Byzantine Groundbreaking 1853 Completed 1864 Specifications Notre-Dame de la Garde is a basilica located in Marseille, France. This ornate Neo-Byzantine church is situated at the highest natural point in Marseille, a 162 m (532 ft) limestone outcrop on the south side of the Old Port. As well as being a major local landmark, it is the site of a popular annual pilgrimage every Assumption Day (August 15). Local inhabitants commonly refer to it as la bonne mère ("the good mother").[1]

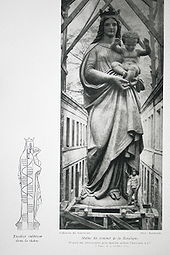

A minor basilica of the Catholic church, it is situated on a limestone peak of 149m (490 feet), on the walls and foundations of an old fort. Built by architect Henri-Jacques Espérandieu in the Neo-Byzantine style, the basilica was consecrated on 5 June 1864. It replaced a church of the same name built in 1214 and reconstructed in the 15th century. The basilica was built on the foundations of a 16th-century fort constructed by Francis I of France to resist the 1536 siege of the city by the Emperor Charles V. The basilica is made up of two parts: a lower church, or crypt, dug out of the rock and in the Romanesque style, and an upper church of Neo-Byzantine style decorated with mosaics. A square bell-tower of 41m (135 feet) is surmounted by a belfry of 12.5m (42 feet) which itself supports a monumental, 11.2m (27 feet) tall statue of the Madonna and Child made out of copper gilded with gold leaf.[2]

The stone used for the construction of the basilica, in particular the green limestone originating in the area surrounding Florence, was discovered to be sensitive to atmospheric corrosion. An extensive restoration took place from 2001 to 2008. This included work on the mosaics, damaged by candle smoke, and also by the impact of bullets during the Liberation of France at the end of World War II.

In Marseilles, Notre-Dame de la Garde is traditionally regarded by the population as the guardian and the protectress of the city.

Chapel in the 13th century

A unique site

The Bay of Marseilles opens westward on to the sea, and is bordered by the hills of the Massif de l'Etoile (Star range) to the north, those of Sainte-Baume to the east, and the Carpiagne and the Massif de Marseilleveyre to the south. From the middle of this broad depression a cretaceous limestone peak rises to a height of 162 metres. At its summit the basilica of Notre-Dame de la Garde has been built.[3]

Following the construction of the basilica, part of the hill was used from 1905 to 1946 as an open-cast quarry. It is estimated that a volume of 800,000 cubic metres of limestone was extracted.[4] The hill, which proceeds uninterrupted in the south towards the heights of the district of Scrape-Sole, is started by a bleeding in which the street of Wood-crowned was open.[5] This artificial cliff is the subject of an important monitoring, with regular visits and preventive purgings to avoid the crumblings. Due to its high elevation, and location close to the coast, the hill quickly became an important observation point and a landmark for shipping. It has thus undoubtedly been used for a considerable period as a lookout point and stronghold. In 1302, Charles II of Anjou ordered one of his ministers to ensure that beacons were set along the Mediterranean coast of Provence; one of these beacon sites was the hill of Notre-Dame du Gard.[6]

The first chapel

In 1214 master Pierre, a Marseilles priest, was inspired to build a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary on the hill known as La Garde. Since the hill belonged to the abbey of Saint-Victor, Pierre had to seek permission from the abbot before he could begin the work.[7] The abbot granted him permission to plant vines, to cultivate a garden there and to build a chapel.[8] The chapel was completed four years later, a fact confirmed in an inventory of 18 June 1218 listing the possessions of the abbey, made for Pope Honorius III, and which identifies a church of Notre-Dame du Gard. After the death of Master Pierre in 1256, Notre-Dame du Gard became a priory. The prior of the sanctuary was at the same time one of the four claustral priors of Saint-Victor.[9] From the foundation of the chapel, donations, known to us from surviving wills, were made in favour of the church, showing a popular devotion which was to grow during subsequent centuries.[10] Indeed the sailors who had escaped with a shipwreck were going to make their thanksgivings and to deposit ex-votos with the furnace bridge of Notre-Dame of the sea located in the church of Notre-Dame-du-Mont; this practice was diverted towards the end of the 16th century with the profit of Notre-Dame of Garde.[11]

This first vault was replaced at the beginning of the 15th century by a more important building which includes, like indicate a document of the officiality of Marseilles, a richly equipped vault dedicated to saint Gabriel.[12]

Fortified town and place of worship from the 16th to 18th centuries

Visit of Francis I

On 3 January 1516, the mother of François I, Louise of Savoy, and his wife the queen Claude, daughter of Louis XII, went to the south of France to find the young king, fresh from his victory at Marignan. On 7 January 1516 they went up to the sanctuary of Notre-Dame de la Garde. A few days later on 22 January 1516, Francis I of France also joined them and went to the vault.[7] During this visit, the king noted that the city of Marseilles was badly defended. The need for a reinforcement of the defensive system became even more obvious in 1524 after the siege of the city by the constable Charles III of Bourbon who joined with Charles Quint, where the city was taken with little effort. François I then decided to build two forts: one on the island of Yew, which became the famous Chateau d'If, the other at the top of la Garde which included the vault.[13] There would be no other example of a coexistence between a military fort and a sanctuary open to the public.[14]

Escutcheon of François I

The construction of the Chateau d'If was faster with an end to work in 1531, while the fort of Notre-Dame de la Garde was finished only in 1536, to resist the arrival of the troops of Charles Quint. For the construction of the fort, stone from the Cap Couronne was used and materials recovered from the demolition of buildings located outside the ramparts of the city and likely to provide a shelter to the enemy troops.[15] Among the destroyed monuments used for construction of the fort was the convent of the Mineurs brothers where Louis of Toulouse was buried and which was located near the courses Belsunce and Saint-Louis.[16] This fort was in the shape of a triangle whose two sides measure approximately 75 meters, the third being of 35 meters. This fort of rather modest importance remains visible on a spur to the west of the basilica; the top of this spur was restored in 1993 to return it to its original state by removing a watch tower installed in 1930. At the top of this spur there is a map of the panorama.

Above a door, one can see the escutcheon of François I, the arms of France on Fleurs de Lys with the salamander below. This escutcheon is very damaged. Close to it on the right-hand side, is a round stone corroded by time with some vestiges of a sculpture which represented the lamb of John the Apostle with his banderole.[17]

Wars of religion

In 1585, the chief of League of Provence, Wines, sought to seize Marseilles and combine with Louis of the Mound-Dariès, second consul of Marseilles. On the night of the 9 April 1585 Dariès occupied the fort of la Garde, from where his guns could fire on the city. But the attack on Marseilles failed, leading to the execution of Dariès and its accomplice.[18]

In 1591, Charles Emmanuel, duke of Savoy, wish to seize abbey of Saint-Victor, building strengthened close to the port. It charges Pierre Bon, baron de Méolhon, governor of Notre-Dame de la Garde, to seize the abbey. In the night of the 16 November 1591 the sior Méolhon seize the abbey which will quickly be taken again by the partisans of Charles de Casaulx, first consul of the town of Marseilles.[19]

In 1594, Charles de Casaulx wants to become Master of the fort of the Guard. For that it sends to it two priests, Trabuc and Cabot, to celebrate the mass in the vault. After the celebration, Trabuc which carries an armour under its cassock, keep silent the captain of the fort. Charles de Casaulx can take possession of the fort and names governor his son Fabio.[20] In 1595 a wall out of W is below built the fort. It is always visible and a carpark is carried out in the re-entrant angle of the wall.[21] After the assassination of Charles de Casaulx the 17 February 1596 by Pierre de Libertat, Fabio is driven out of the fort by his own soldiers.[22]

Last royal visit

Louis XIII during his stay in Marseilles, to horse in spite of the rain to Notre-Dame of la Garde the 9th November 1622. It is received by the governor of the fort, Antoine de Boyer, lord of Bandol.[23] With died of this last occurred the 29 June 1642, Georges de Scudéry, mainly known as a novelist, is named governor; he did not take up his post until December 1644, accompanied by his sister, Madeleine de Scudéry woman of letters, who gives in her correspondence, many descriptions of the place and the surrounding area as well as various festivals or ceremonies. “Friday passed, which was the day after the festival God, you had seen the banderolée citadel from the feet to the head of ten flags and, in swing, the bells of our pinnacle, and an admirable procession returning to the castle. The statue of Notre-Dame de la Garde holding, from her left arm, the naked child and, from her right hand, a bouquet of flowers, was carried by eight penitents veiled like phantoms”.[24] Georges de Scudéry scorns the fort and prefers to live at Lenche square, the aristocratic quarter of the time. The guardianship of the fort is entrusted to a middle-ranking sergeant, named Nicolas.[25]

The only significant event which occurred under the government of Scudéry is the Caze affair in 1650. During the sling, the governor of Provence, the count of Alais, opposed the Parliament of Provence and wanted to repress the Marseilles revolt. Estimating that the fort of la Garde constituted a desirable strategic position, he bribed the sergant Nicolas and on 1 August 1650 installed one of his partisans, David Caze. He thus hoped to offer a support to an attack which could have been made with galères coming from Toulon, a city which was faithful tohim.[25] The consuls of Marseilles reacted to this threat and David Caze was obliged to leave the fort.[26]

In the 18th century

In 1701 dukes from Burgundy and of Berry, grandsons of Louis XIV, go up to the sanctuary. Vauban which succeeded Clerville, the manufacturer of strong Saint Nicolas's Day, studies the possibility of still reinforcing the defense of Marseilles. On 11 April 1701 it presents an imposing project which considers construction d' a vast enclosure which would connect strong the Saint Nicolas's Day to that of Notre-Dame de la Garde and would continue jusqu' with the plain Saint-Michel, currently place Jean-Jaurès, to lead to the quay d' Arenc.[27] This project did not have any continuation.

During plague which hit Marseilles in 1720, the bishop Henri de Belsunce went three times by foot to the chapel at the Notre-Dame de la Garde on 28 September and 8 December 1720 and 13 August 1721 to bless the inhabitants of the city.[28]

Revolutionary period

Closing of the vault

On 30 April 1790 the fort was invaded by anti-clerical revolutionaries who, under pretext of attending a mass in the vault, cross the drawbridge, using a stratagem similar to that adopted by the 'liguers' in 1594.[29] On 7 June 1792, Trinity Sunday, the large traditionally organized procession this day is disturbed by demonstrations. During the return to the sanctuary, the statue of the virgin is covered by a tri-colored scarf and Jesus child capped with the Phrygian cap, icon of the Revolution.

On 23 November 1793 the religious buildings were closed down and worship ceases. On 13 March 1794, the statue of the virgin made in 1661 out of silver, is sent to be melted at the mint of Marseilles which was located at number 22 of Rue Tapis-Vert in the old convent of Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mercy.[30]

A prison for princes

In April 1793, the duke of Orléans Philippe Égalité, his two sons the duke of Montpensier and the count of Beaujolais, his sister Louise, duchess of Bourbon and the prince de Conti were imprisoned for a few weeks at Notre-Dame de la Garde before their transfer to Fort Saint-Jean. In spite of the lack of comfort offered by the old apartments of the governor, the prisoners were able to enjoy the panorama. Each day the duchess of Bourbon, after having attended the mass, went to the terrace of the fort and remained often two hours in contemplation. The princess, who painted well, left a pencil drawing representing a view of Marseilles from the virgin of Notre-Dame de la Garde.[31]

A providential man: Escaramagne

The last auction of the objects belonging to the sanctuary took place on 10 April 1795. The vault having become quite national, Joseph Escaramagne takes it in hiring. Former captain of ship and inhabitant in the vicinity, l' current place of the Colonel-Edon, Escaramagne had deep a devotion for the Virgin. After the resumption of the worship in certain parishes, he writes in September 1800 with the Minister for the war, Lazare Carnot, to authorize the reopening of the sanctuary. But the prefect Charles Delacroix, consulted by the minister gives an unfavorable opinion.[32] It will be necessary to await the 4 April 1807 so that the vault is returned to the worship.[33]

Escaramagne buys with the biddings a statue of the virgin to the child of the 18th-century which came from a convent of monk of Picpus, brood which was close to law courts and which are demolished during the Revolution. It offers this statue to l' Notre-Dame church of the Guard. The sceptre which the virgin held is replaced by a bouquet of flower d' where the name of the statue of “virgin to the bouquet”. To make place with the new statue d' money carried out in 1837, this statue will be given to Chartreuse de Montrieux, then will return in 1979 to the sanctuary.[34] This statue of the virgin to the bouquet is currently exposed to the furnace bridge of the crypt.

Renaissance of the sanctuary

On 4 April 1807, the vault of Notre-Dame de la Garde was reopened for worship. That day there a procession started from the Major bringing to the sanctuary the statue which had been bought by Escaramagne.[35] The traditional procession of the festival of God began again in 1814. Julie Pellizzone mentions this event in her diary: “Sunday 12 June 1814, feastday God, the gunners of the urban guard went morning, as well as the penitent white, to seek Notre-Dame of Garde to bring downtown, following antique use. She was greeted by several cannon blasts. Mass was said, then it is brought to our premises, carried by the penitent ones which had their cap covering the figure, thing which since the Revolution had not taken place.[36]

Enlarging the chapel

In this period the fort itself was almost unused while the number of people visiting the chapel increased significantly. This increase was so great that the 150 sq meter chapel was extended in 1833 with the addition of a second nave, which increased its area to approximately 250 sq meters.[37] The bishop of Marseilles, Fortunate of Mazenod, consecrated this chapel in 1834.

Distinguished visitors

duchess of Berry escaping a shipwreck while returning from Naples, climbed to the chapel on 14 June1816 and left a silver statuette like ex-voto. This statue was unfortunately melted a few years later.[38] Marie Therese of France, daughter of Louis XVI climbed to Notre-Dame de la Garde on 15 May 1823, a day when the mistral was blowing strong. In spite of a strong wind, the duchess made a point of remaining on the terrace to enjoy the beauty of the landscape.[39]

In 1838 the virgin of the Guard had another distinguished visitor: François-René de Chateaubriand.[40]

A new silver statue

Thanks to a gift of 3000 F made by the duchess of Orleans at the time of her trip to Marseilles in May 1823 and various offerings, the clothes industry a new statue of the Virgin is planned in order to replace that which had been sent to the cast iron with Revolution. In 1829 one asks goldsmith Jean-Baptiste Chanuel, Marseilles artist installed street of Dominican to make this statue after a model carried out by the sculptor Jean-Pierre Cortot. At price of five years of work (1829–1834) Marseilles goldsmith carried out this work by the very delicate process of pushed back with the hammer. On 2 July 1837 the statue was blessed by Fortune of Mazenod on Belsunce course then brought to the top of the hill of the Guard. It replaces the statue of the virgin to the bouquet which one gives to chartreuse of Montrieux.[41] and which returned to the crypt in 1979. The two statues of the Virgin to the bouquet and the silver Virgin are thus former to the basilica in which they are exposed.

New bell

The rebuilding of the bell-tower in 1843 enabled it to receive a bell ordered from Lyons founder Gédéon Morel and bought thanks to a subscription. The bell was founded on 11 February 1845[42] and arrived at Marseilles on 19 September 1845. It was deposited in Jean-Jaurès square where it was blessed on Sunday 5 October 1845 by Eugene de Mazenod and baptized “Marie Joséphine”.[43] The godfather was Andre-Elisee Reynard then mayor of Marseilles and the godmother the wife of ship-owner Mr. Wulfran Puget, born Canaple; their name is engraved on the bell.[44] On October 7 the bell which weighs 8,234 kilograms (18,150 lb) is placed on a harnessed carriage of sixteen horses; it is descended from the plain by the street Thiers, the alleys Leon Gambetta, it street Carpet-Green, it Belsunce course, Canebière, it street Paradise, it Pierre-Puget course. The convoy is then reinforced with ten horses what carries their number to twenty-six. On 8 October 1845 the rise of the hill starts to be done with l' also helps of capstans and continues jusqu' at Friday October 10, day of its arrival at the height. The bell is set up on Wednesday October 15.[45] It rang out its first notes on December 8, day of the Immaculate Conception.[46]

On this occasion the poet Joseph Autran composed a poem which finishes as follows:

"Sing, vast bell! sing, bell bénie Répands, spread with floods your powerful harmony; Pour on the sea, the fields, the mounts; And especially as of this hour when your anthem commence Entonne in the skies a song of joy immense Pour the city which we like!"[47]

Like the statues of the Virgin exposed to the interior of the basilica, the bell came before the construction of the current building.

Construction of the current basilica

Negotiations with the army

The person in charge of the vault, the father Jean-Antoine Bernard, asked the ministry for the war on 22 June 1850 for authorization to enlarge the existing vault. On 22 October 1850, the very same day where it left its ministerial functions, it Alphonse Henri, comte d'Hautpoul, Minister for the war, finding the request too vague, give an agreement in principle but ask the commission of temporal to present a project more precise.[48] The 8 April 1851, a new request is addressed for construction d' a new vaster church having practically the surface of the existing buildings, which amounted more not having a building of military use inside the strong.[49] Thanks to the support of the general Adolphe Niel, the committee of the fortifications gives a favorable opinion in its meeting of 7 January 1852. The authorization to build a new vault is given by the Minister for War on 5 February 1852. The studies and the research of the financing can begin.[50]

The project

On 1 November 1852, Monseigneur Eugene de Mazenod requests offerings of the faithful ones. Studies are requested from various architects. The council d' administration of the vault meets on 30 December 1852 in the presence of Mazenod. The project presented by Leon Vaudoyer which works with cathedral of the Major is the only one of Byzantine style romano, while the others are of style neogothic. Each project collects five votes, but the vote of the vicar being dominating, the project of Vaudoyer is retained. The plans were in fact establish by Henri-Jacques Espérandieu, its old pupil only twenty three years Robert Levet, ' ' The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation between l' church and l' army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ' 'ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 120, ISBN 2-903963-75-4. On 23 June 1853 Espérandieu is named architect and develops the project. Well qu' being Protestant, it does not seem that its religion was a major cause of the difficulties encountered with the commission of the sanctuary in charge of the implementation of work. This one decided, without consultation of l' architect, not to put work in adjudication to make play competition, but to entrust them the 9 August 1853 directly with Pierre Berenger, contractor and architect of l' saint-Michel church, which had proposed itself one of the projects neogothic and which was a close relation of Monseigneur Mazenod Denise Jasmin, ' ' Henri Espérandieu, the trowel and the lyre' ' , ED. Act-south-Maupetit, Arles Marseilles, 2003, p. 154 ISBN 2-7427-4411-8. The commission also decides to impose the d' choice to him; artists such as the sculptor Joseph Marius Ramus or the painter Karl Müller of Düsseldorf without worrying to know if their works s' will adapt to l' structure reserve. The choice of Karl Müller was not confirmed thereafter, which allowed l' architect of s' to direct towards a decoration of mosaïquesRevue Marseilles, January 1997, N° 179, p. 84.

A difficult construction

Installation of the first stone by the bishop of Marseilles Monseigneur Eugene de Mazenod takes place on 11 September 1853. Work starts but is very painful because them foundations to make in a very hard rock, and financial problems appear quickly. In 1855 one decides to organize a lottery authorized by the government, but which reports less than envisaged.[51] The financial resources are as much more insufficient than the commission sanctuary decides l' enlarging of the crypt which, instead of being only under the chorus, s' will extend under all the higher vault. In spite of a loan engaged on the clean goods of the bishop, the building site is stopped two years of 1859 to 1861, year of died of Mazenod. The new bishop Patrice Cruice who arrives at the end of the month of August 1861, revival work. The generosity of citizens of all confessions and all social conditions - of Emperor and of Empress which returns visit to the virgin of the Guard on 9 September 1860 with most modest of the Marseillais - allows the completion of work. The dedication of the sanctuary was given on Saturdays 4 June 1864 by the Villecourt cardinal, member of the Roman curia, in the presence of forty-three other bishops. In 1866, a pavement in mosaic is posed in the higher church and the square bell-tower is finished; the bell is installed in October of the same year.

In 1867, one builds on the square bell-tower a cylindrical pedestal or bell-tower intended to receive the monumental statue of the virgin. The financing of the statue is dealt with by the town of Marseilles. The drafts of the statue made by three Parisian artists, Eugene-Louis Lequesne, Aime Millet and Charles Gumery are examined by a jury made up of l' Espérandieu architect, of Bernex, mayor of Marseilles, Jeanron, director of l' school of the Art schools, Bontoux, professor with l' school of sculpture and Luce, president of the civil Court, administrator of the sanctuary of Notre-Dame de la Garde. The project of Lequesne is retenu.[52]

For reasons of cost and weight, copper is retained like matter for the clothes industry of the statue. A very new method for l' time is adopted for the realization of the statue: galvanoplasty, " this art to mould without the help of the feu" G. Aillaud, Y.Georgelin and H.Tachoire, ' ' Marseilles, 2600 years of scientific discoveries, III - Discoverers and découvertes' ' , Publications of the University of Provence, Aix-en-Provence, 2002, p. 13 ISBN 2-85399-504-6, is preferred with the copper pushed back with the hammer. Indeed, according to a scientific report/ratio of the 19 November 1866, use of the electrotype copper allows d' to obtain an irreproachable reproduction and a solidity which will not leave something to be desired anything. Only Purple-Leduc thinks that the products of galvanoplasty will not resist a long time the atmospheric agents with MarseilleG. Aillaud, Y.Georgelin and H.Tachoire, ' ' Marseilles, 2600 years of scientific discoveries, III - Discoverers and découvertes' ' , Publications of the University of Provence, Aix-en-Provence, 2002, p. 14 ISBN 2-85399-504-6. Espérandieu makes carry out the statue in four sections because of the difficulties of its rise on the hill and at the top of the bell-tower. It inserts into the centre of the sculpture an iron arrow, core of a spiral staircase reaching the head of the Virgin for maintenance and the contemplation of the site. This metal structure, which is used as support with the statue, makes it possible to consolidate the whole by connecting it to carcass work of the tower. L' execution of the statue, entrusted to the workshops Christofle, is finished in August 1869. To carry out this work, tanks d' will have had to be used; electrolyse container 90,000 litres (20,000 imp gal; 24,000 US gal) d' a copper sulfate solution and moulds in round bump gutta-perched about it armed heavy 1,500 kilograms (3,300 lb). The first elements are assembled on 17 May 1870 and the dedication is made on 24 September 1870, but without glare, the defeat vis-a-vis the Prussian armies occupying all the spirits Abbot G. Arnaud d' Agnel, ' ' Marseilles, Notre-Dame of Garde' ' , ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1923, p. 146-148. This statue is gilded with the sheet; the gilding which requires 500 grams (18 oz) gold was remade into 1897, 1936, 1963 and 1989 Régis Bertrand, Lucien Tirone, The guide of Marseille, ED. manufacture, Besançon, 1991, p. 242, ISBN|2-7377-0276-3. In March 1871 is formed in Marseilles, at the instigation of Gaston Crémieux, it Commune revolutionary. Helped by garibaldiens, the revolutionists seize prefecture and make captive the prefect. On 26 March 1871 the general Espivent of Villeboisnet is folded up with Aubagne, but undertakes the reconquest of the city as of on April 3 Guiral and Paul Amargier, History of Marseille, Mazarine, 1983, p. 276. The insurrectionists taken refuge in the prefecture are under the fire of the batteries installed in strong Saint Nicolas's Day and in Notre-Dame de la Garde. They capitulate on April 4 and say that the Virgin changed name and is called from now on “Notre-Dame of bombards”[53] Following the death of Espérandieu which occurred on 11 September 1874, Henri Antoine Révoil is charged with the interior decoration of the basilica, in particular of the realization of the mosaics. The construction of the major furnace bridge and installation of the mosaics of the chorus s' carry out in 1882. Unfortunately a fire occurred on 5 June 1884 and destroyed the furnace bridge and mosaic of the chorus; moreover the statue d' money of the Virgin is damaged. The statue and the mosaics are restored and l' furnace bridge rebuilt according to the plans of Révoil. On 26 April 1886 the cardinal Lavigery devotes the new furnace bridge[54] In 1886, stalls carried out in drowning are installed in the chorus; the last mosaics of the side chapels are posed of 1887 to 1892. In 1897, one sets up the two bronze doors of the higher church and the mosaic which surmounts them; the statue of the virgin is regilded for the first time. Final completion of the basilica thus takes place more than forty years after the installation of the first stone.

The funicular

It was not until 1892 that a funicular to ascend the coast was built and known as the lift. The station was located at the lower end of Dragon street, while the upper station led right into a gateway to access the terrace underneath the basilica. There were then only a few degrees to climb to reach the level of the crypt, at 162m. The work lasted two years.

It consisted of two cabins weighing 13 tons with vacuum, circulating on two parallel ways provided with toothed racks. The movement was produced by a system called “to balance d' water”; each cabin, in addition to its two stages being able to receive 50 passengers on the whole, was provided d' a tank d' water of 12 cubic metres.[55] The cabins were connected together by a cable of lift; the tank of the downward cabin was filled d' water (that of the ascending cabin being of course emptied). This ballasting ensured the starting of the system. The difference in level between the two stations was 84m [56]. The water collected with the foot of apparatus with the exit of each voyage was brought back to the top with helps; a pump of 25 units (of truths horsepowers, because the pump was actuated by the vapor). If the journey time were two minutes, the time necessary with the filling of the higher tank exceeded the ten minutes, obliging to space the departures, in spite of l' often considerable multitude. The last emotion, after the rise, was felt lorsqu' it was necessary to cross the footbridge of 100 metres length (built by Eiffel) which overhung the steep slope. It n' had that 5 metres (16 ft) broad and the mistral s' gave to it to heart joy. In the only day of August 15, 1892, the number of the travellers exceeded 15,000 [57][58] It was destroyed after having transported 20 million passengers over 75 years.

The Liberation of France

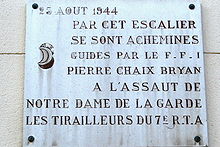

On 24 August 1944 General Joseph de Goislard de Monsabert gave the order to General Sudre to seize the hill of Notre-Dame de la Garde, which was occupied by the German army. But his orders include the condition “step of air raid, not large-scale use of artillery. This legendary hilltop will have to be attacked by infantrymen supported by armoured tanks”.[59] The principal attack was entrusted to lieutenant Pichavant who commanded the 1st company of 7th regiment of Algerian riflemen. On the 25 August 1944 at 6 o'clock in the morning, the troops began moving towards the hill but very slowly because German riflemen guarded the hill to obstruct the advance of soldiers. One French soldier, Pierre Chaix-Bryan, knew the area well and that at No. 26 Cherchel street, now Jules-Moulet street, there is a corridor which made it possible to cross the building and to reach a staircase unknown to the Germans. A commemorative plaque marks the spot. The Algerian riflemen used this staircase and arrived under the command Roger Audibert, with the Cherchel plate. Other soldiers use the staircases of the Notre-Dame ascent which climbs from the boulevard of the same name. The attackers of the northern face were taken under the fire of the casemates and taken with reverse by the shootings of the batteries of strong Saint Nicolas's Day. The support of the tanks is essential.[60]

To the beginning of after midday of this August 25, 1944, the tanks of the 2nd regiment of cuirassiers of the 1 D.B also attacked starting from the Gazzino boulevard, now rue Andre-Ell, and of the rise of the oblats. The tank “Jeanne d' Arc” reaches full whip is stopped place of Colonel Eddon; the three occupants are killed. The tank is always visible. A second tank, the “Jourdan”, change on a mine, but protected by a rocky outcrop, can continue its shootings which will have a decisive effect which will be known only later. Indeed a German warrant officer specialist in the flame throwers will be killed by these shootings; a young inexperienced soldier will prematurely start the fire of the flame throwers which will be inoperative, but especially will make locate the site of the batteries.[60]

Around 3.30 p.m. a section of the first company of the 7th Algerian riflement ordered by Roger Audibert to which he had joined; Ripoll candidate, attacks the hill. It is accommodated by Mgr Borel taken refuge in the crypt. The French flag is hoisted at the top of the bell-tower. In the evening the German officer who ordered the troops of Notre-Dame de la Garde returns. He was wounded and died two days later. The liberation of Marseilles took place in the morning of the 28 August 1944.[61]

Architecture

The exterior of the building is notable for its use of layered stonework of contrasting colours: white Calissane limestone is alternated with layers of green, Golfalina stone in a style reminiscent of Florence. Inside the upper church, no expense was spared to provide a worthy setting for the veneration of the Virgin. Of particular note is the use of a variety of coloured marbles and polychrome pictorial mosaics. Access to the building is gained from a plaza 100 feet (35m) wide leading to a drawbridge. From this one one may either directly enter the crypt or climb a stairway to the entrance porch of the upper church. The building can be seen as a succession of spaces: the porch and bell-tower, a nave flanked by side chapels, the transept, dome, choir and apse.

External

The bell-tower

At a height of 41 meters (130 ft), the square bell-tower located above the entrance porch is made up of two identical storeys of five blind arches, the central arch bearing a window with a small balcony. This is surmounted by a belfry, each face of which is made up of three large bays divided by red granite columns, behind which are placed the louvres. This belfry is topped by a bordered square terrace with an openwork stone balustrade bearing the arms of the city on each side and an angel with a trumpet at each corner. These four statues were carved by Lequesne. From this square terrace a cylindrical bell-tower rises to a height of 12.5 metres (40 feet). This is made of sixteen red granite columns which support a monumental statue of the Virgin Mary, 11.2 metres (36 feet) tall. A staircase within the bell tower allows access to the terrace and the statue. However access is forbidden to the public. One reaches the upper church through the bronze doors designed by Henri Révoil. The central door panels bear the monogram of the Virgin placed within a circle of pearls resembling the rosary. The tympanum above the main entrance is decorated with a mosaic of the Assumption of the Virgin, after an original by Faivre-Duffer.

Side walls

The sides of the nave are divided into three equal parts comprising in their center a window lighting each one a side chapel. Pilaster the S and the arcs consist of stones and archstone X alternate green and white. Ventilators placed at the short-nap cloth of the roadway give a little day to the underground vaults of the crypt. The nave being higher than the side chapels, of geminated bays light the three segments of a sphere of the nave; these geminated bays are not visible terrace.

Transept, dome and apse

Transept lit by the two cross ones geminated surmounted d' a rosette is directed East-West. On its axis s' raise a dome 9 meters in diameter. This dome raised on an octagonal level is composed of thirty two plates with l' intersection of which s' set up a cross. Each face of the octagonal plan is bored d' a window, each one framed of two red granite columns, with which the semicircular arch is surmounted d' a triangular pediment. The semicircular apse is decorated with five framed blind arcades each of two red granite columns. The posterior construction of the buildings of the sacristy hiding place part of l' apse.

Interior

Contrast is seizing between the sobriety of the crypt and the sumptuousness of the higher church. The crypt, low height, is not very enlightened and without decoration while the higher church lit by bays is richly decorated with polychrome marbles and mosaics.

Crypt

In the hall d' entry located under the bell-tower are two marble statues representing Mazenod and the pope Black and white IX, carved by Ramus. In this hall are of share and d' other of l' entry two staircases leading to the higher church. Entirely of Romance style, the crypt is composed d' a nave arched into full curve bordered of six side chapels corresponding exactly to those of l' higher church. The Master furnace bridge is out of stone of Golfalina. Behind this furnace bridge s' raise the statue of the virgin to the bouquet. In the side chapels plates are placed bearing the name of the various givers having answered the call of Cruice. The side furnace bridges are devoted to holy Philomène, saint Andre, holy Rose, Henri saint, holy Louis and saint Benoit Labre who was the model of Paul Verlaine at the time of his conversionJosé Lenzini, Thierry Garot, Notre-Dame of Garde, Giletta, Nice, 2003, p. 109, ISBN 2-903574-91-X. In the two vaults of the bottom, on the right and on the left, two staircases end in the sacristies and the platforms of the chorus and the Master furnace bridge of the high vault; these staircases are not accessible to the public.

Higher Church

Interior dimensions of the higher church are rather modest. The nave has a length of 32.7m. and a width of 14m. Each side chapel measures 3.8m by 5.4m. Inside the higher church is the triumph of polychromy with sumptuous mosaics and columns and marble pilasters with the alternate colours red and white. So for the white Carrara marble marble Carrara marble imposed, on the other hand for the red the choice was very delicate. The Espérandieu architect wanted a red moderated for to harmonize with the mosaics and not too much not to slice with the whiteness of the Carrara marble. The monumental mason Jules Cantini made the discovery with the locality “the beautiful stones” on the commune of That close to Brignoles (VAr) of a red marbled marble layer of yellow and white, receiving a beautiful polish, which was appropriate perfectly. For the high parts is the stucco, c' be-with-to say reconstituted marble, which is adopted. Mosaics of the ceilings and the walls whose developed surface is approximately 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) were carried out of 1886 to 1892 by the Mora company installed with Nimes. The tesselles which came from Venice, were manufactured by craftsmen at the top of their Article Each panel comprises close to 10,000 tesselles with the m2, which represents for the basilica approximately 12 million small squares of 1 with 2 centimetres (0.79 in). These mosaics constitute an exceptional whole by the complexity of its decorations carried out by architects or painters of reputation and by the quality of the tesselles ones. The grounds are covered with approximately 380 sq m of Roman mosaics to the geometrical drawing Robert Levet, ' ' The Virgin of the guard more luminous than jamais' ' , editor association of the field of Our-lady of the Guard, Marseilles, 2008, p. 88.

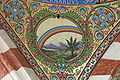

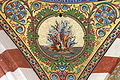

Papered mosaics, the nave creates a tinted supernatural atmosphere of orientalism. It is covered with three cupolas decorated with mosaics carried out in an identical way: on a sowing of flowers are illustrated of the doves in circle around a central floret. The colours of the flowers are different for each cupola: white for the first, blue for the second and red for the third. With the four angles, with the repercussions of the vault on the piles, are represented in medallions, figures summarizing old will. The following medallions are observed:

- 1st cupola: Noah's Ark, left l' arch with the rainbow, Jacob's ladder and burning bush;

- 2nd cupola: Tables of the Law, stick flowered d' Aaron, candlestick with seven branches and censer of the temple;

- 3rd cupola: vine charged with grapes, lily enters the spines, olive branch to the sheets d' money and palm tree.

Mosaics of the first coupole

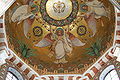

The transept

The large cupola in the middle of the transept is decorated d' a mosaic representing four angels on bottom d' however s' raising ground towards the raised sky and supporting, arms, a crown of pinks qu' they offer to the Virgin Mary represented by her monogram placed at the center of the composition. With the repercussions of the cupola, in the corbellings, the four evangelists are represented: Marc saint symbolized by the lion, Luc saint by the bull, Jean saint by the eagle and Mathieu saint by the man. L' blind arcade of the bedside, above l' apse, contains a mosaic representing l' Annunciation made in Marie: on the right l' Gabriel angel, sent by God, called to Marie “Here that you will conceive in your centre and will give birth to a son and you it will name JésusÉvangile according to Luc saint, chapter I, verse 31”. On the left the Virgin Mary gives her consent.

Sculptures and mosaics of the transept

-

L' Annunciation in Marie. File: St Mathieu.jpg|Mathieu saint.

The chorus

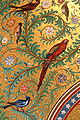

The Master furnace bridge designed by Révoil, carried out by Jules Cantini between 1882 and 1886, is out of white marble with a formed base of five gilded bronze blind arcades resting on posts in lapis lazuli with a decoration of mosaics. The gate vault in vermeil is framed of two columns and two panels of mosaic representing of the doves drinking in a chalice. Behind the furnace bridge draws up a red marble column supporting a capital d' goldsmithery on which is posed the statue of the virgin carried out out of money pushed back with the hammer by the Marseilles goldsmith Chanuel. Mosaic of the bottom of furnace of l' apse represents in a central medallion, a ship on an agitated sea. On the sail of this ship the monogram of the Virgin is reproduced and, in the sky, a star with has and a M interlaced (Ave Maria: I greet you Marie). This medallion is placed in the center d' a sumptuous decoration representing of rinceaux of foliages and thirty two birds; one can notice the peacock, the parrot, the crested one, gorges it blue, the héron, goldfinch etc. Under this mosaic nine medallions connected to each other by the rinceaux ones of foliages are placed appearing the litanies of the virgin.

Mosaic of the half dome of abside

Side chapels

Each side chapel is devoted to a saint. One finds thus while entering and while going towards the chorus:

- on the left: saint Charles Borromée, Lazare saint and Joseph saint;

- on the right: holy Roch, holy Marie Madeleine and Pierre saint. The furnace bridges of these six vaults are similar. On the tomb of each furnace bridge the escutcheon of the titular saint of the vault is reproduced. Jules Cantini carried out these furnace bridges designed by Henri Révoil; it also carried out the statue of Pierre saint and in made gift with the sanctuary. The ceiling of each one of these vaults is decorated d' a mosaic comprising d' a side the name and the blazon of the person who ensured the financing of it and of l' other a symbol corresponding to the saint to which the vault is devoted. One finds thus the reasons following:

- Weapons cardinalices for saint Charles Borromée; giver Mr. and Mrs. J. Gondran (1892);

- Open tomb for Lazare saint; giver Mrs. Edmond Luce born Lavre Luce (1891);

- Lily for Joseph saint; giver Mr. the count Pierre Pastré (1890);

- Scallop and double sack recalling that holy Roch was a pilgrim; giver Mr. and Mrs. Aimé Pastré and their sons Joseph & Emmanuel (1887);

- Vase with perfume for holy Marie Madeleine; giver Mrs. Augustin Fabre and wire (1891);

- Keys of the paradise for Pierre saint; giver Mr. the Count and the Countess Pastré (1889).

Vaults latérales

Long and meticulous restoration: 2001-2008

The interior frontages having aged much and mosaics having been badly restored after the war, of great work of restoration were undertaken of 2001 to 2008 pennies the control of the architect Xavier David. It took four years d' studies before launching work which lasted of 2001 to 2008 and were financed thanks to the participation of the local government agencies and in private gifts of private individuals or d' establishments of the area.

External restoration

If the majority of the stones used proved with time very resistant, it was not in the same way for the called green stone Golfalina. This beautiful stone lasts s' is very quickly degraded under l' effect of industrial and domestic pollution coming in particular from the combustion of coal. It is exhausted on a thickness of 3 by 5 cm.[62] The career close to Florence d' where this stone had been extracted, was closed for a long time. It was necessary to find another place in a vineyard close to Chianti where 150 cubic metres of Golfalina were extracted. The defective stones were replaced by stones identical but treated to resist the pollutionRevue Marseilles, N° 219, p. 94. Moreover certain metal reinforcements while rusting made burst stones. Two of the reinforcements posed a serious problem: that which girdle the top of the room of the bells to reinforce this zone during the swinging of the bell and that which encloses the most part of the bell-tower on which are posed the monumental statue. Certain reinforcements were protected by a cathodic protection of others replaced by stainless steel.

Interior restoration

Work to be undertaken was even more important in the interior. All access, certain stuccos of the high parts damaged by infiltrations have being remade. Then, panels of mosaics, ranges to the Release by the impacts of balls or the glares shells, had been repaired with the techniques of l' time and in the urgency: the tesselles missing ones had been repaired by plaster covered with painting. Moreover, all these mosaics were blackened by the smoke of the candles. The restoration of the mosaics was entrusted to a mosaïste Marseilles Michel Patrizio, whose workmen were trained with the school of mosaic of Spilimbergo, and which perpetuates, in Frioul in the north of Venice, technique of the mosaic. As with l' origin the tesselles ones, elements of mosaic, were provided by the Orsoni workshop of Venice. The most damaged part was the central cupola of the nave which required the change of all the gold mosaics. Certain parts of mosaics, which threatened to fall apart, were consolidated by resin injections.

In the arts

Writers

Many writers described the famous basilica. One can retain the following quotations:

- Valery Larbaud: “That which governs the roads of mercelle which shines above the floods and the soleilla giant upright at the bottom of the hours bleuesla high living of gold of a long country blancPallas Christian of the gaules.[63]

- Paul Arene: “Here that the true good mother, only, that which throne in stiff gold coat of pearls and ruby, under the dome of Notre-Dame de la Garde, cuts hard lapis lazuli encrusted with diamonds instead of stars, condescended to be annoyed against me.[64]

- Chateaubriand: “I hastened to go up to Notre-Dame de la Garde, to admire the sea which border with their ruins the laughing coasts of all the famous countries of Antiquity.[65]

- Marie Mauron: “It is it whom one sees of the sea, first and last on his top very of light hemmed of blue, dominating its Greek Provence which knows or does not know any more that it is it, but the remainder. Who will miss, believing or not, to go up to the Good mother.[66]

- Michel Mohrt: “And it high on the mountain, the good Virgin, the Good mother looked at this crowd, governed the traffics of the false indentity cards, at the black-market with open sky behind the Stock Exchange, with all the attacks, all the denunciations, all the rapes, the Good mother of the Guard which takes care on the sailors who are with ground, - as for those which are at sea, that they démerdent! ”[67]

- André Suarès: “Notre Dame of the Guard is a mast: it oscillates on its skittle. It will take its flight, the basilica, with the virgin who serves to him as huppe.[68]... Thus the basilica perched on the hill of the guard, and the copper statue gilded which they hoisted on the basilica. There, once more, this style which wants to be with the truth novel and Byzantine, without never succeeding in being a style: neither the force of the novel, nor Byzantine science.[69]

Painters of the Basilica

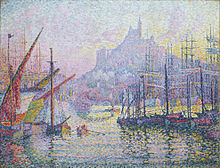

Tableau by Paul Signac

Tableau by Paul Signac

Many painters have shown Marseilles port with Notre-Dame's basilica in the background. Thus Paul Signac, who helped to develop to pointillism, painted a tableau in 1905 that is now shown in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Albert Marquet produced three oeuvres. The first was a drawing executed in ink in 1916 and shown at Musee National d'Art Moderne in Paris. The second is an oil on canvas painted in 1916 entitled “The horse at Marseilles”. This painting, now at the Museum of Fine Arts in Bordeaux, shows a horse on the port quay with the hill of Notre-Dame de la Garde in the background. The third, shown at the Annonciade museum at Saint-Tropez, is called “The Port of Marseilles in fog”; the basilica emerges from a misty landscape where the purification of form is extended. This last painting indicates this painter did not always represent the port of Marseilles from the front. In their liking, he moved his easel to the riverbank side, sometimes close to the town hall to represent the hill of Notre-Dame de la Garde.

Charles Camoin painted two canvases in 1904 on which Notre-Dame de la Garde: “The old port with barrels” which is at the Gelsenkirchen museum and “The Old Port and Notre-Dame de la Garde” shown at the Fine Art museum of Le Havre. This museum also possesses a painting by Raoul Dufy made in 1908, entitled “The Port of Marseilles”. In 1920, Marcel Leprin made a pastel drawing “Notre-Dame de la Garde seen from the town hall”: this work is in the small palace museum in Geneva. Louis-Mathieu Verdilhan, about 1920 “The canal from Fort St. John”; the silhouette of Notre-Dame de la Garde is at the bottom of the painting with a boat in the foreground. This painting is in Paris, at the National Museum of Modern Art.

The Good Mother

The Notre-Dame basilica of the Guard is considered by the Marseilles population as their guardian and the protectoress of the city, hence current naming of 'good mother'.

The ex-votos

A Mediterranean-style religiosity is expressed here with numerous dotive candles and ex-votos offered to the Virgin to thank her for spiritual or temporal grace and to proclaim publicly and remembrance of such grace. One of the oldest documents concerning this practice is a deed of 11 August 1425 in which a certain Jean Aymar paid five guilders for the purchase for wax images offered in recognition of the Virgin.[70] During his voyage in the South of France at the beginning of the 19th century, Aubin-Louis Millin de Grandmaison was struck by the number of ex-voto of Notre-Dame de la Garde: “The way which leads to the oratory is stiff and difficult. The vault is small and narrow, but decorated everywhere with tributes from mariners: on the ceiling small vessels are suspended with their rigs and have their name registered on the stern; they are what the mother of Christ has saved from cruel shipwreck or the fury of pirates and corsairs”.[71] Walls of the side chapels of the two sanctuaries, the crypt and upper church, are covered with a first level of marble slabs. The upper walls of these side chapels are occupied by ex-votos painted placed on several superimposed ranges. The majority of these ex-votos date only from the second half of the 19th century because those from before the Revolution were dispersed during this period. The representations relate to the most numerous shipwrecks and storms. One can also see very different scenes: fire, car accident or railway, patient in his bed etc. Political and social events are also represented. The events of May 68 are the inspiration for one drawing and an Olympic Marseilles flag recalls that the players of the club mounted a pilgrimage to the basilica after a victory. Space has become insufficient, the latest votive plates are placed on the walls of the terraces of the basilica.

Finally the upper church retains many models of boats and planes recently restored and traditionally suspended from the roof of the building.

The symbol of Marseille

Visible from the motorways entering Marseille, Notre-Dame de la Garde is the city's most well-known symbol. It is most-visited site in Marseille,[72] and accommodates hundreds of people each day. For the cardinal Etchegaray, former bishop of Marseille, the Virgin de la Garde "does not form only part of the landscape like Chateau d'If or the Old Port, but it is the living heart of Marseille, its central artery more than the Canebière. It is not the exclusive property of Catholics, it belongs to the human family which lives in Marseille."[73] Notre-Dame de la Garde more remains the high point of the diocese of Marseille even more than the cathedral. It was here that Jean Delay, on 30 August 1944, hoped that deep reforms bring to the poorest living and working conditions more just and human. It was also here that Etchegaray compared, in May 1978, the ravages of unemployment to the those of the plague of Marseille of 1720.[74] Notre-Dame de la Garde is well a window of the diocèse and the best platform of her évêques.

Popular tourist site

While it is difficult to ascertain the exact number of people visiting Notre-Dame de la Garde, it is generally estimated that it receives around a million and half visitors each year, among which there are of course numbers of tourists simply there to admire the view.[75] The motivations of the pilgrims are varied, although many leave messages and inscriptions. One inscription sums up many of these perfectly: "I came here for the peace and the comfort one finds at the feet of the Blessed Virgin, also for the feast for the eyes offered by the basilica, for the panorama, the pure air, the space, and the feeling of liberation.”[76] Square and accesses of the basilica one discovers a splendid panorama of the city of Marseilles.

With the increase in the number of cruise ships making stopover or on the basis of Marseille, excursions to Notre-Dame are a common part of one-city visits to the Ville phocéenne. The basilica is served by bus service from the Old Port (Jean-Ballard Course). Finally there are two ways to climb to the basilica on foot - from either the north or south.

Gallery

References

- ^ Being Provencal. Niranjani Iyer. India Today Travel Plus. IN FOCUS: MARSEILLE. April 2008.

- ^ Official statistics given at the time of a visit to the sanctuary.

- ^ C. Gouvernet, G. Guieu, C. Rousset, Geological guides régionaux, Marseilles, ED. Masson, Pars, 1971 p. 198.

- ^ Revue Marseilles, N° 214, p. 65

- ^ Adrien Blés, Historical Dictionary of the Streets of Marseille, Ed. Jeanne Laffitte, Marseilles, 1989, p. 57, ISBN 2-86276-195-8.

- ^ Abbot G. Arnaud d' Agnel, Marseilles, Notre-Dame of Garde, Tacussel Editions, Marseilles, 1923, p. 29.

- ^ a b Robert Levet, The Virgin of the Guard within the Fortress, Four centuries of cohabitation between Church and Army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 14-15, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Abbé G there. Arnaud d' Agnel, Marseilles, Notre-Dame of Garde , ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1923, p. 13.

- ^ Mr. Chaillan, Small monograph of a large church, Notre-Dame du Gard, Marseille, ED. Moulot, Marseilles, 1931, p. 23.

- ^ Mr. Chaillan, Small monograph of a large church, Notre-Dame de la Garde with Marseille, ED. Moulot, Marseilles, 1931, p. 24.

- ^ Régis of Colombière, Note on the vault and the fort of Notre-Dame of Garde, Typography Vve Marius Olive, Marseilles, 1855, p. 3.

- ^ Francoise Hildesheimer, Notre-Dame de la Garde, the Good mother of Marseille, ED. Jeanne Laffitte, Marseilles, 1985, p. 17 ISBN 2-86276-088-9.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 18-19, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 20 ISBN 2-903963-75-4

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 21, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Louis Méry and F. Guindon, Analytical and chronological history of the acts and the deliberations of the body and the council of the municipality of Marseille, ED. Barlatier Feissat, Marseilles, 1845–1873, 7 vol., T. 3, note 1, p. 335.

- ^ Régis of Colombière, Note on the vault and the fort of Notre-Dame of Garde, Typography Vve Marius Olive, Marseilles, 1855, p. 12.

- ^ Boniface Wolfgang Kaiser, Marseilles at the time of the disorders 1559-1596, ED. school of the high studies in social sciences, Paris, 1991, p. 266, ISBN 2-7132-0989-7.

- ^ Wolfgang Kaiser, Marseilles at the time of the disorders 1559-1596 , ED. school of the high studies in social sciences, Paris, 1991, p. 302 ISBN 2-7132-0989-7. Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 39, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Abbé G. Arnaud d' Agnel, Marseilles, Notre-Dame of Garde, ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1923, p. 45.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 43 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, ' ' The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ' ' ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 46 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation between church and army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 49 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Andre Bouyala d'Arnaud, Evocation of old Marseille, midnight editions, Paris, 1961, p. 365.

- ^ a b Adolphe Crémieux, Marseilles and royalty during the minority of Louis XIV (1643–1660), Bookshop Hatchet, Paris 1917,2 volumes, p. 319.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of la Garde in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 54 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and l' army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 68-69, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ' ' ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 72 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Andre Bouyala d'Arnaud, Evocation of the old Marseille, midnight editions, Paris, 1961, p. 367.

- ^ Adrien Corns, ' ' Historical dictionary of the streets of Marseille' ' , ED. Jeanne Laffitte, Marseilles, 1989, p. 360, ISBN 2-86276-195-8.

- ^ Jean-Baptist Samat, The detention of the princes d'Orleans in Marseilles (1793–1796), Committee of the Marseilles Old man, number 59, third quarters 1993, p. 174.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ' ' ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 85-88 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 91 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 204 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 93, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ ” Julie Pellizzone, Memories, Indigo & Side-women editions, Publications of the University of Provence, Paris, 1995, T. 1 (1787–1815), p. 398 ISBN 2907883933.

- ^ Robert Levet, The Virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation between the church and the army on a hill in Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 102, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Abbé G. Arnaud d' Agnel, Marseilles, Notre-Dame of Garde, ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1923, p. 225.

- ^ André Bouyala d' Arnaud, Evocation of the Marseille' old man; ' , editions of midnight, Paris, 1961, p. 368.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 106, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 104, ISBN 2-903963-75-4

- ^ Abbot G. Arnaud d' Agnel, Marseilles, Notre-Dame of Garde, ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1923, p. 120,

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation between church and army on a Marseilles hill (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 109 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Régis of Colombière, Note on the vault and the fort of Notre-Dame of Garde' ' , Typography Vve Marius Olive, Marseilles, 1855, p. 36.

- ^ Abbé G. Arnaud d' Agnel, Marseilles, Notre-Dame de la Garde, ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1923, p. 121.

- ^ Andre Bouyala d' Arnaud, Evocation of the old Marseille , midnight editions, Paris, 1961,369.

- ^ Andre Chagny, Notre-Dame of Garde, ED. Lescuyer, Lyon, 1950.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation between church and army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 113 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, ' ' The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation between the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ' ' ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 114 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, ' ' The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941) ' ' , ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 116-119 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation between church and army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ' ' ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 123.

- ^ Archives of Marseilles, ' 'Henry Espérandieu, architect of Notre-Dame of Garde' ' , ED. Édisud, Aix-en-Provence, 1997, p. 32 ISBN 2-85744-926-7.

- ^ Robert Levet, ' ' The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), Paul Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 144 ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Robert Levet, The virgin of the Guard in the middle of the bastions, four centuries of cohabitation enters the church and the army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1994, p. 154, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Pierre Gallocher, Marseilles, Zigzags in the passé, ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 4 vol. T. 2,1989, p. 12-13.

- ^ Robert Levet, ' ' This elevator which went up in Good Mère' ' , ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1992, p. 35 ISBN 2-903963-60-6

- ^ Robert Levet, ' ' This elevator which went up in Good Mère' ' , ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1992, p. 38, ISBN 2-903963-60-6. L' advent of l' automobile era killed the funicular. On 11 September 1967 with 18. 30, the funicular ceased any activity due to non-rentabilité.

- ^ Robert Levet, This elevator which went up in Good Mère, ED. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1992, p. 89, ISBN 2-903963-60-6.

- ^ Jean Contruucci, And Marseilles was released August 23-August 28, 1944, ' ' ED. Other Times, Marseilles, 1994, p. 65 ISBN 2-908805-42-1.

- ^ a b Roger Duchêne and Jean Contrucci, Marseille, ED. Beech, 1998, ISBN 2-213-60197-6 p. 671.

- ^ Pierre Guiral, Release of Marseille, ED. Hatchet, 1974, p. 98.

- ^ Robert Levet, The Virgin of the guard more luminous than jamais, editor association of the field of Our-lady of the Guard, Marseilles, 2008, p. 86.

- ^ ”Valery Larbaud, ' ' œuvres' ' , coll library of the pleiad, ED. Gallimard, Paris, 1957, p. 1111

- ^ ”Paul Arene, Tales and news of Provence' ' , ED. Presses of the Rebirth, Paris, 1979, p. 325 ISBN 2-85616-153-7

- ^ ”Chateaubriant, Memories of in addition to-tombe, delivers fourteenth, chapter 2, coll library of the pleiad, ED. Gallimard, Paris, 1951, p. 482

- ^ Marie Mauron, By traversing Provence , ED. Blue floods, Monaco, 1954, p. 161?”

- ^ Michel Mohrt, ' ' My kingdom for a cheval' ' , ED. Albin Michel, Paris, 1949, p. 39

- ^ André Suarès, ' ' Marsiho' ' , ED. Jeanne Laffitte, Marseilles, 1976, p. 83

- ^ Andre Suarès, ' ' Marsiho' ' , ED. Jeanne Laffitte, Marseilles, 1976, p. 129. ”

- ^ Abbé G. Arnaud d' Agnel, Marseilles, Notre-Dame of Garde, éd. Tacussel, Marseilles, 1923, p. 193.

- ^ Aubin-Louis Millin, Travel in the départements of midday of France, Printing works impériale, Paris, 1807–1811, four volumes and an atlas, volume 3, p. 261.

- ^ Regis Bertrand, The Christ of Marseillais, Thune, Marseille, 2008, p. 204 ISBN 978-2-913847-43-9.

- ^ Website of the diocese of Marseilles.

- ^ Francoise Hildesheimer, Notre-Dame de la Garde, Good Mother of Marseille, éd. Jeanne Laffitte, Marseille, 1985, p. 52-53 ISBN 2-86276-088-9.

- ^ Robert Levet, The Virgin of the Guard within the Fortress, Four centuries of cohabitation between Church and Army on a hill of Marseilles (1525-1941), ED. Tacussel, Marseille, 1994, p. 14-15, ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- ^ Jean Chélini, Notre-Dame de la Garde, the heart of Marseille, éd. Other times, Gémenos, 2009, p. 17 ISBN 2-84521-360-3.

- Abbé G. Arnaud d’Agnel, Marseille, Notre-Dame de la Garde, éd. Tacussel, Marseille, 1923

- Régis Bertrand, Le Christ des Marseillais, La Thune, Marseille, 2008, ISBN 978-2-913847-43-9

- Régis Bertrand, Lucien Tirone, Le guide de Marseille, édition la manufacture, Besançon, 1991, ISBN 2-7377-0276-3

- André Bouyala d’Arnaud, Évocation du vieux Marseille, les éditions de minuit, Paris, 1961

- Mgr. M. Chaillan, Petite monographie d’une grande église, Notre-Dame de la Garde à Marseille, éd. Moulot, Marseille, 1931

- Jean Chélini, Notre-Dame de la Garde, le cœur de Marseille, éd. Autres temps, Gémenos, 2009, ISBN 2-84521-360-3

- Pierre Gallocher, Marseille, Zigzags dans le passé, Tacussel, Marseille, 4 volumes, tome 2, Marseille, 1989

- Paul Guiral, Libération de Marseille, Hachette, 1974

- Françoise Hildesheimer, Notre-Dame de la Garde, la Bonne Mère de Marseille, éd. Jeanne Laffitte, Marseille, 1985, ISBN 2-86276-088-9

- Denise Jasmin, Henry Espérandieu, la truelle et la lyre, Actes-Sud-Maupetit, Arles Marseille, 2003, ISBN 2-7427-4411-8

- Wolfgang Kaiser, Marseille au temps des troubles 1559-1596, éditions de l’école des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris, 1991 ISBN 2-7132-0989-7

- José Lenzini, Thierry Garot, Notre-Dame de la Garde, édition Giletta, Nice, 2003, ISBN 2-903574-91-X

- Robert Levet, La Vierge de la garde plus lumineuse que jamais, éditeur association du domaine de Notre-dame de la Garde, Marseille, 2008

- Robert Levet, Cet ascenseur qui montait à la Bonne Mère, éd. Tacussel, Marseille, 1992, ISBN 2903963606

- Robert Levet, La vierge de la Garde au milieu des bastions, quatre siècles de cohabitation entre l’église et l’armée sur une colline de Marseille (1525-1941), Paul Tacussel, Marseille, 1994, ISBN 2-903963-75-4

- Arnaud Ramière de Fortanier, Illustration du vieux Marseille, ed. Aubanel, Avignon, 1978, ISBN 2700600800

Further reading

- Félix Reynaud, Ex-voto de Notre-Dame de la Garde. La vie quotidienne. édition La Thune, Marseille, 2000, ISBN 2-913847-08-0

- Félix Reynaud, Ex-voto marins de Notre-Dame de la Garde. édition La Thune, Marseille, 1996, ISBN 2-9509917-2-6

External links

- Office du Tourisme

- notredamedelagarde.com

- Diocèse de Marseille

- Photos personnelles de Notre dame de la Garde. Photographies prisent par Thierry.A des Docks.

Coordinates: 43°17′2.5″N 5°22′16″E / 43.284028°N 5.37111°E

Categories:- Wikipedia articles needing cleanup after translation

- Buildings and structures in Marseille

- Neo-Byzantine architecture

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.