- Ulster Irish

-

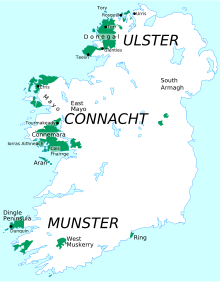

Note: This page uses the IPA to transcribe Irish. Readers familiar with other conventions may wish to see International Phonetic Alphabet for Irish for a comparison of the IPA system with those used in learners' materials.  The percentage of people in each administrative area in Ulster who have the ability to speak Irish. (Counties of the Republic of Ireland and District council areas of Northern Ireland.)

The percentage of people in each administrative area in Ulster who have the ability to speak Irish. (Counties of the Republic of Ireland and District council areas of Northern Ireland.)

Ulster Irish is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the Province of Ulster. The largest Gaeltacht region today is in County Donegal, so that the term Donegal Irish is often used synonymously. Nevertheless, records of the language as it was spoken in other counties do exist, and help provide a broader view of Ulster Irish. When the recommendations of the first Comisiún na Gaeltachta were drawn up in 1926, there were regions qualifying for Gaeltacht recognition in the Sperrin Mountains on the border between County Tyrone and County Londonderry, as well as in the northern Glens of Antrim around Rathlin Island. The report also makes note of small pockets of Irish speakers in Northwest County Cavan, Southeast County Monaghan, and the far south of County Armagh. However, these small pockets vanished early in the 20th century while the Gaeltacht of the Sperrin Mountains survived until the 1950s and the Glens of Antrim Gaeltacht survived until the 1970s. The last native speaker of Rathlin Island Irish died in 1985.

In the 1960s, six families in Belfast formed the Shaw's Road 'Gaeltacht', which has survived and even grown.[1][2] The Irish-speaking area of the Falls Road in West Belfast has recently been designated the 'Gaeltacht Quarter'.[3] Manx and the southern dialects of Scottish Gaelic share similarities with Ulster Irish, due to their historical connections with Ulster.

Contents

Lexicon

The Ulster dialect contains many words not used in other dialects, or used otherwise only in the west of County Mayo. In other cases, a semantic shift has resulted in quite different meanings attaching to the same word in Ulster Irish and in other dialects. Some of these words include:

- amharc, "look" (elsewhere amharc, breathnaigh and féach; this latter means rather "try" or "attempt" in Ulster)

- bomaite, "minute" (elsewhere nóiméad, nóimint, neómat, etc.)

- cluinim "I hear" (southern cloisim, but cluinim is also attested in South Tipperary). In fact, the initial c- tends to be lenited even when it is not preceded by any particle (this is because there was a leniting particle in Classical Irish: do-chluin yielded chluin in Ulster)

- eallach "cattle" (southern beithíoch "one head of cattle", beithígh "cattle")

- gamhain "calf" (southern lao and gamhain)

- gasúr "boy" (southern garsún, garsún means "child" in Connemara)

- girseach "girl" (southern gearrchaile and girseach)

- bealach, ród "road" (southern and western bóthar and ród (cf. Scottish Gaelic rathad, Manx Gaelic raad), and bealach "way"). Note that bealach alone is used as a preposition meaning "towards" (literally meaning in the way of: d'amharc sé bealach na farraige = "he looked towards the sea"

- ag déanamh is used to mean "to think" as well as "to make" or "to do", síleann, ceapann and cuimhníonn is used in other dialects, as well as in Ulster Irish.

- druid "close" (southern and western dún; in other dialects druid means "to move in relation to or away from something", thus druid ó rud = to shirk, druid isteach = to close in)

- eiteogaí "wings" (southern sciatháin)

- sópa "soap" (standard gallúnach, Connemara gallaoireach)

- stócach, "youth", "young man", "boyfriend" (Southern = "gangly, young lad")

- cál "cabbage" (southern gabáiste)

- fá "about, under" (standard faoi Munster fé, fí and fá is only used for 'under'; mar gheall ar and i dtaobh = "about")

- Gaeilg, Gaelic "Irish" (standard, Western Gaeilge, Southern Gaoluinn, Manx Gaelg, Scottish Gàidhlig)

- caidé (cad é) atá? "what is?" (Connacht céard tá; Munster cad a thá, cad é a thá, dé a thá, Scotland dé tha)

- tábla "table" (western and southern bord and clár, Scotland bòrd

- cá huair "when?" (Connacht cén uair; Munster cathain, cén uair)

- faoileog "seagull" (standard faoileán)

- falsa "lazy" (southern and western leisciúil, fallsa = "false, treacherous")

- the word iontach "wonderful" is used as an intensifier instead of the prefix an- used in other dialects.

In other cases, a semantic shift has resulted in quite different meanings attaching to the same word in Ulster Irish and in other dialects. Some of these words include:

- cloigeann "head" (southern and western ceann; elsewhere, cloigeann is used to mean "skull")

- capall "mare" (southern and western láir; elsewhere, capall means "horse")

Phonology

The phonemic inventory of Ulster Irish (based on the dialect of Gweedore[4]) is as shown in the following chart (see International Phonetic Alphabet for an explanation of the symbols). Symbols appearing in the upper half of each row are velarized (traditionally called "broad" consonants) while those in the bottom half are palatalized ("slender"). The consonants /h, n, l/ are neither broad or slender.

Consonant

phonemesLabial Coronal Dorsal Glottal Bilabial Labio-

dentalLabio-

velarDental Alveolar Alveolo-

palatalPalatal Velar Plosive pˠ

pʲbˠ

bʲt̪ˠ

d̪ˠ

ṯʲ

ḏʲ

c

ɟk

ɡ

Fricative/

Approximantfˠ

fʲ

vʲw

sˠ

ʃ

ç

jx

ɣ

h Nasal mˠ

mʲn̪ˠ

n

ṉʲ

ɲŋ

Tap ɾˠ

ɾʲLateral

approximantl̪ˠ

l

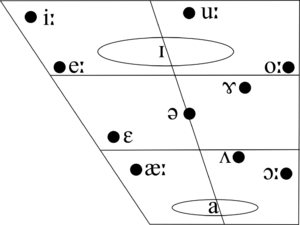

ḻʲThe vowels of Ulster Irish are as shown on the following chart. These positions are only approximate, as vowels are strongly influenced by the palatalization and velarization of surrounding consonants.

The long vowels have short allophones in unstressed syllables and before /h/.

In addition, Ulster has the diphthongs /ia, ua, au/.

Some characteristics of the phonology of Ulster Irish that distinguish it from the other dialects are:

- The only broad labial continuant is the approximant [w]. In other dialects, fricative [vˠ] is found instead of or in addition to [w]. No dialect makes a phonemic contrast between the approximant and the fricative, however.

- Often in Ulster dialects, [tʲ] can become [tʃ] as in "teach" (Pronounced as the English "ch"). Likewise [dʲ] can become [dʒ] as in "dearg" (Pronounced as the English "j"). This is particularly evident in younger speakers of this dialect. Such pronunciation of the slender "t" and "d" is also the case in Scottish Gaelic and Manx.

- There is a three-way distinction among coronal nasals and laterals: /n̪ˠ ~ n ~ ṉʲ/, /l̪ˠ ~ l ~ ḻʲ/, and there is no lengthening or diphthongization of short vowels before these sounds and /m/. Thus, while ceann "head" is /cɑːn/ in Connacht and /caun/ in Munster, in Ulster it is /can̪ˠ/

- /ɔː/ corresponds to the /oː/ of other dialects. The Ulster /oː/ corresponds to the /au/ of other dialects.

- Long vowels are shortened when in unstressed syllables.

- /n/ is realized as [r] (or is replaced by /r/) after consonants other than [s]. This happens in Connacht as well.

- Orthographic -adh in unstressed syllables is always [u] (this includes verb forms).

- Unstressed orthographic -ach is pronounced [ax], [ah], or [a].

Morphology

Initial mutations

Ulster Irish has the same two initial mutations, lenition and eclipsis, as the other two dialects and the standard language, and mostly uses them the same way. There is, however, one exception: in Ulster, a dative singular noun after the definite article is lenited (e.g. ar an chrann "on the tree") (as is the case in Scottish and Manx), whereas in Connacht and Munster, it is eclipsed (ar an gcrann), except in the case of den, don and insan, where lenition occurs in literary language. Both possibilities are allowed for in the standard language.

Verbs

Irish verbs are characterized by having a mixture of analytic forms (where information about person is provided by a pronoun) and synthetic forms (where information about number is provided in an ending on the verb) in their conjugation. In Ulster and North Connacht the analytic forms are used in a variety of forms where the standard language has synthetic forms, e.g. molann muid "we praise" (standard molaimid, muid being a back formation from the verbal ending -mid and not found in the Munster dialect, which retains sinn as the first person plural pronoun as does Scots Gaelic and Manx Gaelic) or mholfadh siad "they would praise" (standard mholfaidís). The synthetic forms, including those no longer emphasised in the standard language, may be used in short answers to questions.

The 2nd conjugation future stem suffix in Ulster is -óch- (pronounced [ah]) rather than -ó-, e.g. beannóchaidh mé [bʲan̪ˠahə mʲə] "I will bless" (standard beannóidh mé [bʲanoːj mʲeː]).

Some irregular verbs have different forms in Ulster from those in the standard language. For example:

- (gh)níom (independent form only) "I do, make" (standard déanaim) and rinn mé "I did, made" (standard rinne mé)

- tchíom [t̠ʲʃiːm] (independent form only) "I see" (standard feicim, Southern chím, cím (independent form only))

- bheiream "I give" (standard tugaim, southern bheirim (independent only)), ní thabhram or ní thugaim "I do not give" (standard only ní thugaim), and bhéarfaidh mé/bheirfidh mé "I will give" (standard tabharfaidh mé, southern bhéarfad(independent form only))

Particles

In Ulster the negative particle cha (before a vowel chan, in past tenses char - Scottish/Manx Gaelic chan, chan do) is sometimes used where other dialects use ní and níor. The form is more common in the north of the Donegal Gaeltacht. Cha cannot be followed by the future tense: where it has a future meaning, it is followed by the habitual present.[citation needed] It triggers a "mixed mutation": /t/ and /d/ are eclipsed, while other consonants are lenited. In some dialects however (Gweedore), cha eclipses all consonants, except b- in the forms of the verb 'to be', and sometimes f- :

Ulster Standard English Cha dtuigim Ní thuigim "I don't understand" Chan fhuil sé Níl sé (contracted from ní fhuil sé) "He isn't" Cha bhíonn sé Ní bheidh sé "He will not be" Cha phógann muid/Cha bpógann muid Ní phógaimid "We do not kiss" Chan ólfadh siad é Ní ólfaidís é "They wouldn't drink it" Char thuig mé thú Níor thuig mé thú "I didn't understand you" Syntax

The Ulster dialect uses the present tense of the subjunctive mood in certain cases where other dialects prefer to use the future indicative:

- Suigh síos anseo aige mo thaobh, a Shéimí, go dtugaidh (dtabhairidh, dtabhraidh) mé comhairle duit agus go n-insidh mé mo scéal duit.

- Sit down here by my side, Séimí, till I give you some advice and tell you my story.

The verbal noun can be used in subordinate clauses with a subject different from that of the main clause:

- Ba mhaith liom thú a ghabháil ann.

- I would like you to go there.

References

- ^ Nig Uidhir, Gabrielle (2006) “The Shaw’s Road urban Gaeltacht: role and impact.” In: Fionntán de Brún (ed.), Belfast and the Irish Language. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 136-146.

- ^ Mac Póilin, Aodán (2007) "Nua-Ghaeltacht Phobal Feirste: Ceachtanna le foghlaim?" In: Wilson McLeod (Ed.) Gàidhealtachdan Ùra; Leasachadh na Gàidhlig agus na Gaeilge sa Bhaile Mhòr. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University, pp. 57-59.

- ^ "All roads lead to the Gaeltacht Quarter". Belfast City Council. http://www.belfastcity.gov.uk/news/news.asp?id=515. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- ^ Ní Chasaide, Ailbhe (1999). "Irish". Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–16. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

See also

- Ulster Scots language

- Mid Ulster English

- Scottish Gaelic

External links

Irish linguistics History Sociolinguistics Connacht Irish · Munster Irish · Newfoundland Irish · Ulster Irish · Status of the language · outside IrelandGrammar Writing Names Personal and family names · List of personal namesCategories:- Irish dialects

- Ulster

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.