- Deinotherium

-

Deinotherium

Temporal range: Middle Miocene–Early Pleistocene

Mounted Deinotherium skeleton Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Proboscidea Suborder: †Deinotheroidea Family: †Deinotheriidae Subfamily: †Deinotheriinae Genus: †Deinotherium

Kaup, 1829Species D. bozasi (Arambourg, 1934)

D. giganteum (Kaup, 1829)

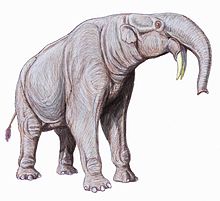

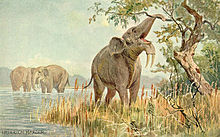

D. indicum (Falconer, 1845)Deinotherium ("terrible beast"), also called the Hoe tusker,[1] was a large prehistoric relative of modern-day elephants that appeared in the Middle Miocene and continued until the Early Pleistocene. During that time it changed very little. In life it probably resembled modern elephants, except that its trunk was shorter, and it had downward curving tusks attached to the lower jaw.

Deinotherium is the third largest land mammal known to have existed; only Paraceratherium and Mammuthus sungari were larger, although Mammuthus imperator may have rivaled it in size. Males were generally between 3.5 and 4.5 metres (12 and 15 feet) tall at the shoulders although large specimens may have been up to 5 m (16 ft). Their weight is estimated to have been between 5 and 10 tonnes (5.5 and 11 US Standard tons), with the largest males weighing in excess of 14 tonnes (15.4 US Standard tons).[2] Deinotherium's range covered parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe. Adrienne Mayor, in The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology In Greek and Roman Times, has suggested that deinothere fossils found in Greece helped generate myths of archaic giant beings. A tooth of a deinothere found on the island of Crete, in shallow marine sediments of the Miocene[3] suggests that Crete was closer or connected to the mainland during the Messinian Salinity Crisis.

Contents

Evolutionary Relationships

Deinotherium is the type genus of the family Deinotheriidae, evolving from the smaller, early Miocene Prodeinotherium. These proboscideans represent a totally distinct line of evolutionary descent to that of other elephants, one that probably diverged very early in the history of the group as a whole. The large group to which elephants belong formerly contained several other related groups: besides the deinotheres there were the gomphotheres (some of which had shovel-like lower front teeth), and the mastodons. Only elephants survive today.

Paleoecology

The way Deinotherium used its curious tusks has been much debated. It may have rooted in soil for underground plant parts like roots and tubers, pulled down branches to snap them and reach leaves, or stripped soft bark from tree trunks. Deinotherium fossils have been uncovered at several of the African sites where remains of prehistoric hominid relatives of modern humans have also been found.

Characteristics

The following description is for D. giganteus but in general applies to the other two species as well.[4]

Permanent tooth formula 0-0-2-3/1-0-2-3 (deciduous 0-0-3/1-0-3), with vertical cheek tooth replacement. Two sets of bilophodont and trilophodont teeth. Molars and rear premolars tapiroid, vertical shearing teeth, and show that deinotheres became an independent evolutionary branch very early on; other premolars used for crushing. The cranium is short, low, and flattened on the top (in contrast to more advanced proboscids, which have a higher and more domed forehead; the implication may be that deinotheres were less intelligent than other proboscids), with very large, elevated occipital condyles. The nasal opening is retracted and large, indicating a large trunk. The rostrum is long and the rostral fossa broad. Mandibular symphyses (the lower jaw-bone) is very long and curved downward, which, with the backward curved tusks, is a distinguishing feature of the group; it possessed no upper tusks.

Deinotherium is distinguished from its predecessor Prodeinotherium by its much greater size, greater crown dimensions, and reduced development of posterior cingula ornamentation in the second and third molar.

Species

Three species are recognized, all of great size.

Deinotherium giganteum Kaup 1829

Deinotherium giganteum is the type species, and is described above. It is primarily a late Miocene species, most common in Europe, and is the only species known from the circum-Mediterranean. Its last reported occurrence is from the middle Pliocene of Romania (2 to 4 million BP). An entire skull, found in the Lower Pliocene beds of Eppelsheim, Hesse-Darmstadt in 1836, measured 4 ft (1.2 m) in length and 3 ft (.9 meters) in breadth, indicating an animal exceeding modern elephants in size.

Deinotherium indicum Falconer 1945

Deinotherium indicum is the Asian species, known from India and Pakistan. It is distinguished by a more robust dentition and p4-m3 intravalley tubercles. D. indicum appears in the middle Miocene, and is most common in the late Miocene. It disappears from the fossil record about 7 million years BP (late Miocene).

Deinotherium bozasi Arambourg 1934

Deinotherium bozasi is the African species. It is characterized by a narrower rostral trough and smaller but higher nasal aperture, and a higher and narrower cranium, and shorter mandibular symphysis, than the other two species. D. bozasi appears at the beginning of the late Miocene, and continues there after the other two species have died out elsewhere. The youngest fossils are from the Kanjera Formation, Kenya, about a million years old (early Pleistocene)

Deinotherium in popular culture

Deinotherium was shown in the fourth episode of BBC's Walking with Beasts. The animal was shown to live side by side with the early human ancestor Australopithecus, the Chalicothere Ancylotherium, and the primitive cat Dinofelis in Ethiopia about 3.2 million years ago.

Deinotherium was also depicted in Karel Zeman's live action/stop motion film Journey to the Beginning of Time. One of the characters in the film initially mistakes it for an elephant.

References

- ^ http://www.cincymuseum.org/educators_researchers/educators/teacher_resources/afriacaelephant_edu_guide.pdf page 18

- ^ Walking with Beasts, Episode 4 "Next of Kin", BBC Documentary, 2001

- ^ Athanassiou, A. 2004. On a Deinotherium (Proboscidea) finding in the Neogene of Crete. Carnets de Géologie/Notebooks on Geology.

- ^ Sanders, W.J., 2003, chap 10, Proboscidea, in Mikael Fortelius (ed) Geology and paleontology of the Miocene Sinap Formation, Turkey, Columbia University Press, New York

- Carroll, R.L. (1988), Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, WH Freeman & Co.

- Colbert, E. H. (1969), Evolution of the Vertebrates, John Wiley & Sons Inc (2nd ed.)

- Harris, J.M. (1976) Evolution of feeding mechanisms in the family Deinotheriidae (Mammalia: Proboscidea). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 56: 331-362

- Athanassios Athanassiou, On a Deinotherium (Proboscidea) finding in the Neogene of Crete: abstract

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Dinotherium". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Dinotherium". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- FactFile: Deinotherium

Categories:- Deinotheriids

- Miocene mammals

- Pliocene mammals

- Pleistocene mammals

- Pleistocene extinctions

- Prehistoric mammals of Africa

- Megafauna of Africa

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.