- Mother India

-

For other uses, see Mother India (disambiguation).

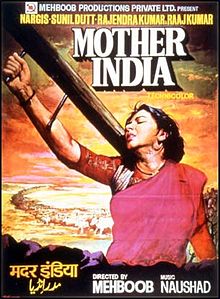

Mother India

Film posterDirected by Mehboob Khan Produced by Mehboob Khan Written by Mehboob Khan

Wajahat Mirza

S. Ali RazaStarring Nargis

Sunil Dutt

Rajendra Kumar

Raaj KumarMusic by Naushad Cinematography Faredoon A. Irani Editing by Shamsudin Kadri Studio Mehboob Productions Release date(s) 25 October 1957 Running time 172 minutes Country India Language Hindi Mother India (Hindi: मदर इण्डिया, Urdu: مدر انڈیا) is a 1957 Hindi film epic, written and directed by Mehboob Khan and starring Nargis, Sunil Dutt, Rajendra Kumar and Raaj Kumar. The film, a melodrama, is a remake of Mehboob Khan's earlier film, Aurat (1940). It is the story of a poverty-stricken village woman named Radha who, amid many other trials and tribulations, struggles to raise her sons and survive against an evil money-lender. Despite her hardship, she sets a goddess-like moral example of what it means to be an Indian woman, yet kills her own criminal son at the end for the greater moral good. She represents India as a nation in the aftermath of independence.

The film ranks among the all-time Indian box office hits and has been described as "an all-time Indian blockbuster" and "perhaps India's most revered film". Mother India belongs to a small collection of films, including Kismet (1943), Mughal-e-Azam (1960) and Sholay (1975) which continue to be watched daily throughout India and are considered to be definitive Hindi cultural film classics. The film was India's first submission for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1958 and was chosen as one of the five nominations for the category.[1]

Contents

Plot

The film begins with construction completion of a water canal to the village, set in the present. Radha (Nargis), as the 'mother' of the village, is asked to open the canal and remembers back to her past when she was newly married.

The wedding between Radha and Shamu (Raaj Kumar) was paid for by Radha's mother-in-law who raised a loan from the moneylender, Sukhilala. This event starts the spiral of poverty and hardship which Radha endures. The conditions of the loan are disputed, but the village elders decide in favour of the moneylender, after which Shamu and Radha are forced to pay three quarters of their crop as interest on the loan of 500 rupees. Whilst trying to bring more of their land into use to alleviate their poverty, Shamu's arms are crushed by a boulder. He is ashamed of his helplessness and is humiliated by others in the village; deciding that he is no use to his family, he leaves and does not return. Soon after, Radha's mother-in-law dies. Radha continues to work in the fields with her two sons and gives birth again. Sukhilala offers to help alleviate her poverty in return for Radha marrying him, but she refuses to "sell herself". A storm sweeps through the village, destroys the harvest, and kills Radha's youngest child. Though at first the villagers begin to migrate, they decide to stay and rebuild on the urging of Radha.

The film then skips forward several years to when Radha's two surviving children, Birju (Dutt) and Ramu (Rajendra Kumar), are young men. Birju, embittered by the exactions of Sukhilala since he was a child, takes out his frustrations by pestering the village girls, especially Sukhilala's daughter. Ramu, by contrast, has a calmer temper and is married soon after. Though he becomes a father, his wife is soon absorbed into the cycle of poverty in the family. Birju's anger finally becomes dangerous and, after being provoked, attacks Sukhilala and his daughter, lashing out at his family. He is chased out of the village and becomes a bandit. On the day of the wedding of Sukhilala's daughter, Birju returns to take his revenge. He kills Sukhilala and takes his daughter. Radha, who had promised that Birju would not do harm, shoots Birju, who dies in her arms. The film ends in the present day with her opening of the canal and reddish water flowing into the fields.

Cast

- Nargis as Radha

- Sunil Dutt as Birju

- Rajendra Kumar as Ramu

- Raaj Kumar as Shamu (Radha's Husband)

- Kanhaiyalal as Sukhilala

- Jilloo Maa

- Kumkum as Champa

- Sheela Naik as Kamla

- Mukri as Shambu

- Azra as Chandra

- Master Sajid Khan as a young Birju

- Master Surendra as a young Ramu

Production

Script

The title of the film is taken from American author Katherine Mayo's 1927 polemical book Mother India, in which she attacked Indian society, religion and culture. The book created a sensation on three continents.[2] Written against the demands for self-rule and Indian independence, Mayo pointed to the treatment of India's women, the untouchables, the animals, the dirt, and the character of its nationalistic politicians. Mayo singled out the "rampant" and fatally weakening sexuality of its males to be at the core of all problems, leading to masturbation, rape, homosexuality, prostitution, venereal diseases, and, most importantly, too early sexual intercourse and premature maternity. Mayo created an outrage across India, and her book was burned along with an effigy of its author.[3] It was criticised by Mahatma Gandhi as a "report of a drain inspector sent out with the one purpose of opening and examining the drains of the country to be reported upon".[4] The book prompted over fifty angry books and pamphlets to be published in response to Mother India to highlight Mayo's errors and false perception of Indian society which had become one of the most powerful influences on the American people's view of India in history.[5]

Khan had the idea for the film and the title as early as 1952; in October that year, he approached the import authorities on a matter related to producing the film.[6] In 1955, the Indian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Indian Ministry of Information and Broadcasting learned of the title of the forthcoming film and demanded that director Mehboob Khan send them the script for review, suspicious that the film was based on the book and a possible threat to national interest.[7] The film team dispatched the script along with a two-page letter on 17 September 1955 saying:

"There has been considerable confusion and misunderstanding in regard to our film producing Mother India and Mayo's book. Not only are the two incompatible but totally different and indeed opposite. We have intentionally called our film Mother India, as a challenge to this book, in an attempt to evict from the minds of the people the scurrilous work that is Miss Mayo's book."[8]The script was thus intentionally written in a way which promoted the empowerment of women in Indian society, the power to resist the sexual advances of men, and the maintenance of a sense of moral dignity and purpose as individuals, contrary to what Mayo had claimed in her book. Khan drew upon inspiration from another American author, Pearl S. Buck and her books The Good Earth (1931) and The Mother (1934), which were made into feature films by Sidney Franklin in 1937 and 1940 respectively.[8] Khan originally drew upon these influences in making the 1940 film Aurat, the original version of Mother India,[9] although an unrelated Indian film had been directed under the name of Mother India in 1938.[8] Khan worked diligently on the script and was aided with the dialogue by Wajahat Mirza and S. Ali Raza. Some of the stylistic elements to the 1957 film show similarities with the 1926 Vsevolod Pudovkin Soviet silent movie Mother (based on a novel by Maxim Gorky) and Our Daily Bread (1934), directed by King Vidor.[10] In turn, the film would provide an inspiration for many later films, including Yash Chopra's Deewar, a breakthrough film for Amitabh Bachchan and would later be remade by the Telugu film industry as Bangaru Talli (1971) and in Tamil as Punniya Boomi (1978).[10]

Filming

Several of the internal scenes for the film were shot at Mehboob Studios in Bandra, Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1956, although Mehboob Khan and cinematographer Faredoon A. Irani attempted to shoot as often as possible on location to try to make the film as realistic as possible, with a touch of splendour.[11] Other scenes were shot in various cities in the states of Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh.[12] Mehboob insisted that the film be shot in 35mm by cinematographer Irani.[13] Contemporary cinematographer Anil Mehta has noted the mastery of Irani's cinematic techniques in shooting the film, including his "intricate tracks and pans, the detailed mise en scène patterns Irani conceived, even for brief shots – in the studios as well as on location".[13] The film took about three years to make from early organisation, planning, and scripting to filming completion.[14] In a November 1956 interview, after production for the film had wound down, Nargis described the film shoot and character portrayal as the most demanding of her career.[15]

During filming, an accident occurred during the fire scene when the fire grew out of control and trapped Nargis. She was saved by co-star Sunil Dutt who quickly grabbed a blanket, plunged inside, and rescued her.[16] Nargis fell in love with Dutt, who plays her son in the film, and they were married within a year.[16] Playback singer Lata Mangeshkar reportedly donated her earnings of over one hundred rupees from the film to charitable causes she was involved with at the time, and on 5 October 1957 the production team, Indra Films, donated 300 rupees to a religious person in Delhi.[17] The production team had planned the film release for Indian Independence Day on 15 August, but the film was released over two months later.[18]

Themes

The term "Mother India" has been defined as "a common icon for the emergent Indian nation in the early 20th century in both colonialist and nationalist discourse".[19] The film, an archetypal nationalistic picture, was symbolic in that it demonstrated the euphoria of "Mother India" in a nation which had only been independent for 10 years, and it had a long-lasting cultural impact upon the Indian people.[20] It had major significance in terms of the patriotism and the changing situation in the nation at the time, and how the country was functioning without British authority.[21] Rosie Thomas highlighted the themes of "female chastity, modern nationalism and morality" as being central to the film, identifying the discourses around female sexuality, modern nationalism, and their political implications as they intersect.[22][23] Lonely Planet described the film as "perhaps the most compelling film about the role of women in rural India, a moving tale about love, loss and the maternal bond".[24]

The film draws upon Hindu mythology, with the deity-couple Krishna and his lover Radha, and the Hindu epic characters like Sita, Sati Savitri, and Draupadi.[10][20] Nargis's Mother India is a metonymic representation of a Hindu woman, reflecting Hindu fundamentalism, with high moral values and the concept of what it means to be a mother to society through self-sacrifice.[20] Mother India can also be seen as a metaphor of the trinity of mother, God, and a dynamic nation.[25][26] In the wider context, her character is allegorical of what it means to be a mother in general.[27][28] The Mother India figure is an icon in several respects, being associated with a goddess, her function as a wife, as a lover, and even compromising her femininity at the end of the film by playing the role of Vishnu the Preserver and Shiva the Destroyer, masculine gods.[29] However, while aspiring to traditional Hindu values, it is important to note that the character of Mother India also represents the changing role of the mother in Indian films and an Indian society in that the mother is not always subservient or dependent on her husband, refining the relationship to the male gender or patriarchal social structures.[30] There is considerable ambiguity in the film in which the mother figure acts as a provider, sacrificing aspects of her own life while also as a destroyer, annihilating her own son, something extremely rare in Hindi cinema.[31]

Part of the major success of the film may be attributed to the importance of Indian womanhood with Indian cultural values and that the character of Mother India represents an ideological figure to the people, with her strong values and moral guidance, despite suffering from poverty and hardship, which is relevant to many.[31] In his book, Terrorism, media, liberation, John David Slocum argues that like Satyajit Ray's classic masterpiece Pather Panchali (1955), Khan's Mother India has vied for alternative definitions of Indianness. However, he emphasises that the film is an overt mythologising and feminising of the nation in which Indian audiences around the globe have used their pure imagination to define it in the nationalistic context, given that in reality the storyline is about a poverty-stricken peasant from northern India, not than a true ideal of a modernising, powerful nation.[32]

Jyotika Virdi has argued that in her chastity, Mother India channels her sexual desires into maternal love for her sons who effectively become "substitute erotic subjects".[31] Parallels are drawn with Gandhi's personification of the Indian woman as a goddess, acquiring certain masculine traits as they gain power as the goddesses did in Hindu mythology, but it is a power which is made more subtle by their virtue and acquiescence.[33] For instance, in a pamphlet published with the intention to introduce the film in the social context to western audiences, it described Indian women as being "an altar in India", that Indians "measure the virtue of their race by the chastity of their women", and that the "Indian mothers are the nucleus around which revolves the tradition and culture of ages."[34]

While the nationalistic representation of Hindu values may seem unusual in that the "Mother India" figure was portrayed by a Muslim actress and directed by a Muslim director,[20][35] people such as Salman Rushdie stated that Bombay cinema is "highly syncretic", and its "hyphenated Hindu-Muslim nature is present in not only its discourses and production practices but indeed its very ideology".[36] Rushdie describes Nargis's portrayal of Mother India as follows:

"In Mother India, a piece of Hindu myth-making directed by a Muslim socialist, Mehboob Khan, the Indian peasant women is idealised as bride, mother, and producers of sons, as long-suffering, stoical, loving, redemptive, and conservatively wedded to the maintenance of the social status quo. But for Bad Birju, cast out from his mother's love, she becomes, as one critic mentioned, 'that image of an aggressive, treacherous, annihilating mothers who haunts the fantasy of Indian males."[36]Mother India's actions at the end of the film in shooting her own son Birju have been said to "rupture the traditional mother-son relationship in order to balance the moral universe".[37] The shooting stance of Nargis at the end of the film is one of the all time iconic images of Hindi cinema. Parama Roy describes Nargis's identification with her role in the film as being "as much about Nargis dead as it is about Nargis alive" and highlights on-screen and off-screen real-life events in her own life which embodied her character of Radha.[22] Roy and Das Guptar have seen Nargis's portrayal of a Hindu woman, being a Muslim, as an allegory of the increasing symbiosis of religions in a multicultural and multiethnic society, in that "only a Muslim can assume the iconic position of a Hindu maternal figure".[38][39] Echoing this religious tolerance is the fact that Mother India was warmly received by countries in the Arab world, and in Algeria the film was still packing cinema houses ten years after its release.[37][40]

Reception

The film premiered at the Liberty cinema in Bombay and in Calcutta during Diwali week on 25 October 1957 and ran for a whole year at the cinema.[18][16][39] The film netted a reported Rs. 1,06,35,95,000 (inflation-adjusted as of 2004), making it the highest grossing Bollywood film ever at the time.[41][42][43] The success of the film led to Khan naming his next film Son of India. Released in 1962, it was not well received.[7][44]

Baburao Patel of Filmindia described Mother India after its release as "the greatest picture produced in India during forty and odd years of film-making" and later added that no other actress would have been able to perform the role as Nargis did.[39] The film has since been described as "perhaps India's most revered film", a "cinematic epic" and Mehboob Khan's best known work.[10][14] It has been described as an "all-time blockbuster", which ranks highly amongst India's most successful films.[45] A 1983 Channel 4 documentary into Bombay cinema described the film as setting a benchmark in Indian cinema for subsequent films to aspire to.[46] Mother India belongs to only a small collection of films, including Kismet (1943), Mughal-e-Azam (1960), Sholay (1975) and Hum Aapke Hain Koun...! (1994), which continue to be heavily watched daily throughout India and are viewed as definitive Hindi films with cultural significance.[46][47] Mother India is still watched daily in cinemas across India today.[48] It was also acclaimed across the Arab world, in the Middle East, parts of Southeast Asia and North Africa and continued to be shown in countries such as Algeria at least ten years after its release.[40][46] It is ranked #80 in Empire magazines "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[49] In 2005, Indiatimes Movies ranked the movie amongst the Top 25 Must See Bollywood Films.[50] It was also listed among the only two Hindi films in the 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die list (the other being Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge).[51] It was ranked third in the British Film Institute's poll of "Top 10 Indian Films" of all time.[52]

The film, Nargis, and Khan received numerous awards and nominations, and Nargis won the Filmfare Best Actress Award and became the first Indian woman to receive the Best Actress award at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival.[53] The film won the Filmfare Best Movie Award[41] and scooped several other awards including Filmfare Best Director Award for Khan,[54] Filmfare Best Cinematographer Award for Faredoon Irani,[55] and Filmfare Best Sound Award for R. Kaushik.[15] The film was India's first submission for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1958 and was chosen as one of the five nominations for the category.[56] However, the submitted entry was dramatically different from the original version released in India. The version sent to the Academy was edited down to 120 minutes, cutting at least 40 minutes from the film for the benefit of a foreign audience. The 120-minute version was later distributed in the US and UK by Columbia Pictures.[57] The film came close to winning the Academy Award but lost to Federico Fellini's Nights of Cabiria by a single vote.[58]

Music

Mother India Soundtrack album by Naushad Released 1957 Recorded Mehboob Studios[59] Genre Film soundtrack Label Sa Re Ga Ma Naushad chronology Uran Khatola

(1955)Mother India

(1957)Sohni Mahiwal

(1958)The score and soundtrack for the movie was composed by Naushad, and the lyrics were penned by Shakeel Badayuni. It made the list of "100 Greatest Bollywood Soundtracks Ever", as compiled by Planet Bollywood, although was not particularly well received upon release, with critics believing it didn't match the high pitch and quality of the film.[15][60] The soundtrack consists of 12 songs, and features vocals by Mohammed Rafi, Shamshad Begum, Lata Mangeshkar, Manna Dey, etc. Planet Bollywood gave the album 7.5 of 10 stars.[61]

Mother India is the earliest example of a Hindi film containing Hollywood-style classical music in a film. An example is during the scene in which Birju runs away from his mother and rejects her motherly care and goodness.[47] It features a powerful symphonic orchestra with strings, woodwinds and trumpets.[47] This orchestral music contains extensive chromaticism, diminished seventh, and augmented scales which are played loudly.[47] It also features violin tremolos. The piece is unmelodic and effectively creates tension over such a negative moment in the film.[47] This use of a western-style orchestra in Indian cinema influenced many later films such as Mughal-e-Azam (1960), which features similar discordal orchestral music to create atmosphere at tense moments in the film.[47] The song "Holi Aayi Re Kanhai", sung by Shamshad Begum, has been cited as a typical Hindi film song which is written for and sung by a female singer, with an emotional charge which appeals to a mass audience.[62]

No. Title Singer(s) Length 1. "Chundariya Katati Jaye" Manna Dey 3:15 2. "Nagari Nagari Dware Dware" Lata Mangeshkar 7:29 3. "Duniya Men Hum Aaye Hain" Lata Mangeshkar, Meena Mangeshkar, Usha Mangeshkar 3:36 4. "O Gaadiwale" Shamshad Begum, Mohammed Rafi 2:59 5. "Matwala Jiya Dole Piya" Lata Mangeshkar, Mohammed Rafi 3:34 6. "Dukh Bhare Din Beete Re Bhaiya" Shamshad Begum, Mohammed Rafi, Manna Dey, Asha Bhonsle 3:09 7. "Holi Aayi Re Kanhai" Shamshad Begum 2:51 8. "Pi Ke Ghar Aaj Pyari Dulhaniya Chali" Shamshad Begum 3:19 9. "Ghunghat Nahin Kholoongi Saiyan" Lata Mangeshkar 3:10 10. "O Mere Lal Aaja" Lata Mangeshkar 3:11 11. "O Janewalo Jao Na" Lata Mangeshkar 2:33 12. "Na Main Bhagwan Hoon" Mohammed Rafi 3:24 See also

- List of submissions to the 30th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Indian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

- ^ "The 30th Academy Awards (1958) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. http://www.oscars.org/awards/academyawards/legacy/ceremony/30th-winners.html. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ Mrinalini Sinha:Introduction. In: Sinha (ed.): Selections from Mother India. Women's Press, New Delhi 1998.

- ^ "Short bio (by Katherine Frick)". Pabook.libraries.psu.edu. http://www.pabook.libraries.psu.edu/palitmap/bios/Mayo__Katherine.html. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ "Teaching Journal: Katherine Mayo's Mother India (1927)". Lehigh.edu. 7 February 2006. http://www.lehigh.edu/~amsp/2006/02/teaching-journal-katherine-mayos.html. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ Jayawardena, Kumari (1995). The white woman's other burden: Western women and South Asia during British colonial rule. Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-415-91104-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=vJ9MCPdcGrsC&pg=PA99. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Chatterjee (2002), p.10

- ^ a b Chatterjee (2002), p.20

- ^ a b c Sinha (2006), p.248

- ^ Gulzar, Govind Nihalani, Saibal Chatterjee (2003). Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema. Popular Prakashan. p. 55. ISBN 978-81-7991-066-5. http://books.google.co.in/books?id=8y8vN9A14nkC. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d Pauwels, Heidi Rika Maria (2007). Indian literature and popular cinema: recasting classics. Routledge. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-415-44741-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=LiXU4ihgMpgC&pg=PA178. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Chatterjee (2002), p.21

- ^ "Mother India (1957)". Mooviees.com. http://www.mooviees.com/36286/locations. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b Chatterjee (2002), p.21

- ^ a b Thoraval, Yves (2000). The cinemas of India. Macmillan India. ISBN 978-0-333-93410-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=-OpkAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Reuben, Bunny (December 1994). Mehboob, India's DeMille: the first biography. Indus. p. 233. ISBN 978-81-7223-153-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=ExhlAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Mother India". Rediff.com. http://www.rediff.com/entertai/2002/feb/15dinesh.htm. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Chatterjee (2002), p.19

- ^ a b Sinha (2006), p.249

- ^ Siddiqi, Yumna (2008). Anxieties of Empire and the fiction of intrigue. Columbia University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-231-13808-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=K4OA_Ike8EoC&pg=PA177. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d Grewal, Inderpal; Kaplan, Caren (1994). Scattered hegemonies: postmodernity and transnational feminist practices. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 84–6. ISBN 978-0-8166-2138-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=XPG65ZOhcWsC&pg=PA84. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Guha, Ramachandra (15 September 2008). India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy. Pan Macmillan. p. 730. ISBN 978-0-330-39611-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=29lXtwoeA44C&pg=PA730. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b Majumdar, Neepa (25 September 2009). Wanted Cultured Ladies Only!: Female Stardom and Cinema in India, 1930s–1950s. University of Illinois Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-252-07628-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=TdM2Ben3alIC&pg=PA151. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Myrsiades, Kostas; McGuire, Jerry (August 1995). Order and partialities: theory, pedagogy, and the "postcolonial". SUNY Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7914-2639-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=60TSFrajgE8C&pg=PA63. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Bindloss, Joe (1 October 2009). Northeast India. Lonely Planet. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-74179-319-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=D_bYWjJOe9cC&pg=PA59. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Kavoori, Anandam P.; Punathambekar, Aswin (August 2008). Global Bollywood. NYU Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-8147-4799-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=2CqERCzWn5gC&pg=PA231. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Asian cinema: a publication of the Asian Cinema Studies Society. Asian Cinema Studies Society. 1996. p. 101. http://books.google.com/books?id=uSsIAQAAMAAJ. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Ghosh-Schellhorn, Martina; Alexander, Vera (1 February 2006). Peripheral centres, central peripheries: India and its diaspora(s). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 190. ISBN 978-3-8258-9210-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=MCz682epff8C&pg=PA190. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Kaur, Raminder (2005). Performative politics and the cultures of Hinduism: public uses of religion in Western India. Anthem Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-84331-139-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=Cen2k9kiWW8C&pg=PA244. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Mishra (2002), p.69

- ^ Gokulsing, K.; Dissanayake, Wimal (2004). Indian popular cinema: a narrative of cultural change. Trentham Books. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-85856-329-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=_plssuFIar8C&pg=PA44. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Virdi, Jyotika (2003). The cinematic imagination: Indian popular films as social history. Rutgers University Press. pp. 114–8. ISBN 978-0-8135-3191-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=u8PKObcYMDIC&pg=PA114. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Slocum, John David (July 2005). Terrorism, media, liberation. Rutgers University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-8135-3608-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=jCLKTz7rRa8C&pg=PA236. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Bahri, Deepika; Vasudeva, Mary (1996). Between the lines: South Asians and postcoloniality. Temple University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-56639-468-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=gxAxJGhvVlgC&pg=PA229. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Fong, Mary; Chuang, Rueyling (2004). Communicating ethnic and cultural identity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7425-1738-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=0cbV7n0kM0cC&pg=PA125. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Roy, Parama (1998). Indian traffic: identities in question in colonial and postcolonial India. University of California Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-520-20487-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=xp82WhOGBnAC&pg=PA168. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b Mishra (2002), p.62

- ^ a b Heide, William Van der (2002). Malaysian cinema, Asian film: border crossings and national cultures. Amsterdam University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-90-5356-580-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=k3HTdu1HuWQC&pg=PA237. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Mishra (2002), p.63

- ^ a b c Mishra (2002), p.65

- ^ a b Gopal, Sangita; Moorti, Sujata (16 June 2008). Global Bollywood: travels of Hindi song and dance. U of Minnesota Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8166-4579-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=19JBf6oDOy0C&pg=PA28. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b Bose, Derek (2006). Everybody wants a hit: 10 mantras of success in Bollywood cinema. Jaico Publishing House. p. 1. ISBN 978-81-7992-558-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=wv_mmculJ8kC&pg=PA1. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Bose, Mihir (2006). Bollywood: a history. Tempus. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7524-2835-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=6LAaAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Business India. A.H. Advani. 2005. http://books.google.com/books?id=gLNIAAAAYAAJ. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Sadoul, Georges; Morris, Peter (1972). Dictionary of film makers. University of California Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-520-02151-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=PvsZikRu-hAC&pg=PA172. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Dissanayake, Wimal (1993). Melodrama and Asian cinema. Cambridge University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-521-41465-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=C-Y6811S3agC&pg=PA181. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Mishra (2002), p.66

- ^ a b c d e f Morcom, Anna (30 November 2007). Hindi film songs and the cinema. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 139–44. ISBN 978-0-7546-5198-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=kfVdxiSm-aYC&pg=PA139. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Gledhill, Christine (1991). Stardom: industry of desire. Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-415-05218-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=v2vPOcm4y94C&pg=PA117. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema:80. Mother India". Empire. http://www.empireonline.com/features/100-greatest-world-cinema-films/default.asp?film=80. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "25 Must See Bollywood Movies – Special Features-Indiatimes – Movies". The Times Of India (India). Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. http://replay.waybackmachine.org/20090207173522/http://movies.indiatimes.com/Special_Features/25_Must_See_Bollywood_Movies/articleshow/msid-1250837,curpg-21.cms. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ "Mother India". 1001beforeyoudie. http://www.1001beforeyoudie.com/. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Top 10 Indian Films". British Film Institute. 2002. http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/imagineasia/guide/poll/india. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Dawar, Ramesh (1 January 2006). Bollywood Yesterday-Today-Tomorrow. Star Publications. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-905863-01-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=TO6Fmi8FraUC&pg=RA1-PA84. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Ganti, Tejaswini (2004). Bollywood: a guidebook to popular Hindi cinema. Psychology Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-415-28854-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=GTEa93azj9EC&pg=PA96. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Reed, Sir Stanley (1 January 1958). The Times of India directory and year book including who's who. Bennett, Coleman.. http://books.google.com/books?id=lXEiAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ General Studies History 4 Upsc. Tata McGraw-Hill. 1 November 2005. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-07-060447-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=yWfeU9eQd5YC&pg=SL3-PA158. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Kabir, NM. (2010). "Commentary" in The Dialogue of Mother India. New Delhi: Niyogi Books.

- ^ "For Bollywood, Oscar is a big yawn again". Thaindian News. 24 February 2008. http://www.thaindian.com/newsportal/entertainment/for-bollywood-oscar-is-a-big-yawn-again_10020729.html. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Notes of Naushad... tuneful as ever". The Hindu. 13 May 2004. http://www.hindu.com/mp/2004/05/13/stories/2004051300820100.htm. Retrieved 7 March 2011. "Naushad himself recorded chorus music for Mughal-e-Azam, and songs for Amar and Mother India on the main shooting floor of the famous Mehboob Studios."

- ^ 100 "Greatest Bollywood Soundtracks Ever". Planet Bollywood. http://www.planetbollywood.com/displayArticle.php?id=060306044135 100. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Planet Bollywood". Planet Bollywood. http://www.planetbollywood.com/displayReview.php?id=042806015458. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ Ranade, Ashok Da. (1 January 2006). Hindi film song: music beyond boundaries. Bibliophile South Asia. p. 361. ISBN 978-81-85002-64-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZI1wqkWsIjYC&pg=PA361. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

Bibliography

- Chatterjee, Gayatri (2002), Mother India, British Film Institute, ISBN 978-0-85170-917-8, http://books.google.com/books?id=FvAKAQAAMAAJ

- Mishra, Vijay (2002), Bollywood cinema: temples of desire, Routledge, pp. 62–87, ISBN 978-0-415-93015-4, http://books.google.com/books?id=8Q8Z9Ukwn6EC&pg=PA65

- Sinha, Mrinalini (2006), Specters of Mother India: the global restructuring of an Empire, Duke University Press, pp. 248–253, ISBN 978-0-8223-3795-9, http://books.google.com/books?id=xI2LClkTrFIC&pg=PA248

External links

- Mother India at the Internet Movie Database

- Mother India at the TCM Movie Database

- Mother India at AllRovi

- Mother India at Rotten Tomatoes

- Mother India at Bollywood Hungama

Filmfare Award for Best Movie 1954–1960 Do Bigha Zamin (1954) · Boot Polish (1955) · Jagriti (1956) · Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje (1957) · Mother India (1958) · Madhumati (1959) · Sujata (1960)

1961–1980 Mughal-e-Azam (1961) · Jis Desh Men Ganga Behti Hai (1962) · Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1963) · Bandini (1964) · Dosti (1965) · Himalaya Ki God Mein (1966) · Guide (1967) · Upkar (1968) · Brahmachari (1969) · Aradhana (1970) · Khilona (1971) · Anand (1972) · Be-Imaan (1973) · Anuraag (1974) · Rajnigandha (1975) · Deewar (1976) · Mausam (1977) · Bhumika (1978) · Main Tulsi Tere Aangan Ki (1979) · Junoon (1980)

1981–2000 Khubsoorat (1981) · Kalyug (1982) · Shakti (1983) · Ardh Satya (1984) · Sparsh (1985) · Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1986) · no award (1987) · no award (1988) · Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1989) · Maine Pyar Kiya (1990) · Ghayal (1991) · Lamhe (1992) · Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar (1993) · Hum Hain Rahi Pyar Ke (1994) · Hum Aapke Hain Kaun...! (1995) · Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1996) · Raja Hindustani (1997) · Dil To Pagal Hai (1998) · Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1999) · Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (2000)

2001–present Kaho Naa... Pyaar Hai (2001) · Lagaan (2002) · Devdas (2003) · Koi... Mil Gaya (2004) · Veer-Zaara (2005) · Black (2006) · Rang De Basanti (2007) · Taare Zameen Par (2008) · Jodhaa Akbar (2009) · 3 Idiots (2010) · Dabangg (2011)

Categories:- 1957 films

- Indian films

- Hindi-language films

- Epic films

- Filmfare Best Movie Award winners

- Films directed by Mehboob Khan

- Films about women in India

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.