- Neisseria

-

Neisseria

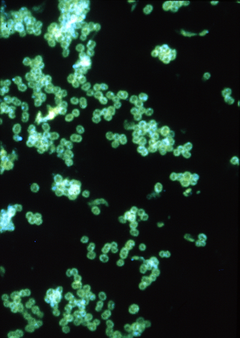

Fluorescent antibody stain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Scientific classification Kingdom: Bacteria Phylum: Proteobacteria Class: Betaproteobacteria Order: Neisseriales Family: Neisseriaceae Genus: Neisseria

Trevisan, 1885Species N. bacilliformis

N. cinerea

N. cuniculi

N. denitrificans

N. elongata

N. flavescens

N. gonorrhoeae

N. lactamica

N. macacae

N. meningitidis

N. mucosa

N. pharyngis

N. polysaccharea

N. sicca

N. subflavaThe Neisseria is a large genus of commensal bacteria that colonize the mucosal surfaces of many animals. Of the 11 species that colonize humans, only two are pathogens. N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae often cause asymptomatic infections, a commensal-like behavior. Most gonoccocal infections are asymptomatic and self-resolving, and epidemic strains of the meningococcus may be carried in >95% of a population where systemic disease occurs at <1% prevalence. Neisseria are Gram-negative bacteria included among the proteobacteria, a large group of Gram-negative forms. Neisseria are diplococci that resemble coffee beans when viewed microscopically.[1]

Contents

Species

Pathogens

Genus (family Neisseriaceae) of parasitic bacteria that grow in pairs and occasionally tetrads, thrive best at 98.6°F (37°C) in the animal body or serum media.

The genus includes:

- N. gonorrhoeae (also called the gonococcus), which causes gonorrhea.

- N. meningitidis (also called the meningococcus), one of the most common causes of bacterial meningitis and the causative agent of meningococcal septicaemia.

Nonpathogens

This genus also contains several, believed to be commensal, or nonpathogenic, species, like:

- Neisseria bacilliformis

- Neisseria cinerea

- Neisseria elongata

- Neisseria flavescens

- Neisseria lactamica

- Neisseria macacae

- Neisseria mucosa

- Neisseria polysaccharea

- Neisseria sicca

- Neisseria subflava

However, some of these can be associated with disease.[2]

History

The genus Neisseria is named after the German bacteriologist Albert Neisser, who in 1879 discovered its first example, Neisseria gonorrheae, the pathogen which causes the human disease gonorrhea. Neisser also co-discovered the pathogen that causes leprosy, Mycobacterium leprae. These discoveries were made possible by the development of new staining techniques which he helped to develop.

Biochemical identification

All the medically significant species of Neisseria are positive for both catalase and oxidase. Different Neisseria species can be identified by the sets of sugars from which they will produce acid. For example, N. gonorrheae makes acid from only glucose, however N. meningitidis produces acid from both glucose and maltose.

Polysaccharide capsule N. meningitidis has a polysaccharide capsule that surrounds the outer membrane of the bacterium and protects against soluble immune effector mechanisms within the serum. It is considered to be an essential virulence factor for the bacteria.[3] N. gonorrhea possesses no such capsule.

Vaccine

Diseases caused by N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, are a significant health problem worldwide, the control of which are largely dependent on the availability and widespread use of comprehensive meningococcal and gonococcal vaccines. Development of Neisserial vaccines has been challenging due to the nature of these organisms, in particular the heterogeneity, variability and/or poor immunogenicity of their outer surface components. As strictly human pathogens, they are highly adapted to the host environment but have evolved several mechanisms to remain adaptable to changing microenvironments and avoid elimination by the host immune system. Currently, serogroup A, C, Y and W-135 meningococcal infections can be prevented by vaccines. However there is no comprehensive serogroup B vaccine, and the prospect of developing a gonococcal vaccine is remote.[4]

Antibiotic resistance

Diseases caused by the pathogenic Neisseria (N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis) have been successfully treated with antibiotics for the past 70 years. However, there is increasing prevalence of strains with resistance to antibiotics. Given the global nature of gonococcal and meningococcal diseases, the worldwide distribution of antibiotics, differing social practices in controlling and monitoring antibiotic availability, and geographical differences in treatment regimens, it is likely that the global problem of antibiotic resistance will continue in the foreseeable future. By understanding the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in gonococci and meningococci, resistance to antibiotics currently in clinical practice can be anticipated and the design of novel antimicrobials to circumvent this problem can be undertaken more rationally.[5]

International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference (IPNC)

The International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference (IPNC) occurs every two years and is a forum for the presentation of cutting-edge research on all aspects of the genus Neisseria. This includes immunology, vaccinology and physiology and metabolism of Neisseria meningitidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and the commensal species. The first IPNC took place in 1978 and the most recent one was in September 2008. Normally the location of the conference switches between North America and Europe but took place in Australasia for the first time in 2006, where the venue was located in Cairns, Australia.

References

- ^ Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ^ Tronel H, Chaudemanche H, Pechier N, Doutrelant L, Hoen B (May 2001). "Endocarditis due to Neisseria mucosa after tongue piercing". Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7 (5): 275–6. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00241.x. PMID 11422256. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1198-743X&date=2001&volume=7&issue=5&spage=275.

- ^ Ullrich, M (editor) (2009). Bacterial Polysaccharides: Current Innovations and Future Trends. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-45-5.

- ^ Seib KL, Rappuoli, R (2010). "Difficulty in Developing a Neisserial Vaccine". Neisseria: Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-51-6.

- ^ Shafer WM et al. (2010). "Molecular Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance Expressed by the Pathogenic Neisseria". Neisseria: Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-51-6.

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.