- Oneida people

-

For other uses, see Oneida (disambiguation).

Oneida Total population 100,000+ Regions with significant populations  United States (Wisconsin, New York)

United States (Wisconsin, New York) Canada (Ontario)

Canada (Ontario)Languages Onyota'aka, English, other Iroquoian dialects

Religion Kai'hwi'io, Kanoh'hon'io, Kahni'kwi'io, Christianity, Longhouse, Handsome Lake, Other Indigenous Religion

Related ethnic groups Seneca Nation, Onondaga Nation, Tuscarora Nation, Mohawk Nation, Cayuga Nation, other Iroquoian peoples

The Oneida (Onyota'a:ka or Onayotekaono, meaning the People of the Upright Stone, or standing stone, Thwahrù·nęʼ[1] in Tuscarora) are a Native American/First Nations people and are one of the five founding nations of the Iroquois Confederacy in the area of upstate New York. The Iroquois call themselves Haudenosaunee ("The people of the longhouses") in reference to their communal lifestyle and the construction of their dwellings.

Originally the Oneida inhabited the area that later became central New York, particularly around Oneida Lake and Oneida County.

Contents

The People of the Standing Stone

The name Oneida is the English mispronunciation of Onyota'a:ka. Onyota'a:ka means "People of the Standing Stone". The identity of the People of the Standing Stone is based on a legend in which the Oneida people were being pursued on foot by an enemy tribe. The Oneida people were chased into a clearing within the woodlands and suddenly disappeared. The enemy of the Oneida could not find them and so it was said that these people had turned themselves into stones that stood in the clearing. As a result, they became known as the People of the Standing Stone.

There are older legends in which the Oneida people self-identify as the "Big Tree People". Not much is written about this and Iroquoian elders would have to be consulted on the oral history of this identification. This may simply correspond to other Iroquoian notions of the Great Tree of Peace and the associated belief system of the people.

Individuals born into the Oneida Nation are identified according to their spirit name, or what most outsiders now call an Indian name, their clan, and their family unit within a clan. Each gender, clan and family unit within a clan all have particular duties and responsibilities. Clan identities go back to the Creation Story of the Onyota'a:ka peoples. The people identify with three clans: the Wolf, Turtle or Bear clans. A person's clan is the same as his or her mother's clan.

Although colonizing forces tried to assimilate or extinguish the Original Nations of North America, the majority of the Oneida Nation people who descend from the Oneida Settlement can still identify their clan. Further, if a person does not have a clan because their mother is not Oneida, then the Nation still makes provisions for customary adoptions into one of the clans. The act of adopting is primarily a responsibility of the Wolf clan, so many adoptees are identified as Wolf.

History

American Revolution

The Oneidas, along with the five other tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy, initially maintained a policy of neutrality in the American Revolution. This policy allowed the Confederacy increased leverage against both sides in the war, because they could threaten to join one side or the other in the event of any provocation. Neutrality quickly crumbled, however. The preponderance of the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga sided with the Loyalists and British. For some time, the Oneida continued advocating neutrality and attempted to restore consensus among the six tribes of the Confederacy. But ultimately the Oneida, as well, had to choose a side. Because of their proximity and relations with the rebel communities, most Oneida favored the colonists. In contrast, the pro-British tribes were closer to the British stronghold at Fort Niagara. In addition, the Oneida were influenced by the Protestant missionary Samuel Kirkland, who had spent several decades among them and through whom they had begun to form stronger cultural links to the colonists.

The Oneida officially joined the rebel side and contributed in many ways to the war effort. Their warriors were often used to scout on offensive campaigns and to assess enemy operations around Fort Stanwix (also known as Fort Schuyler). The Oneida also provided an open line of communication between the rebels and their Iroquois foes. In 1777 at the Battle of Oriskany, about fifty Oneida fought alongside the colonial militia. Many Oneida formed friendships with Philip Schuyler, George Washington, the Marquis de La Fayette, and other prominent rebel leaders. These men recognized the Oneida contributions during and after the war. The US Congress declared, "sooner should a mother forget her children" than we should forget you.[2]

Although the tribe had taken the colonists' side, individuals within the Oneida nation possessed the right to make their own choices. A minority supported the British. As the war progressed and the Oneida position became more dire, this minority grew more numerous. When the important Oneida settlement at Kanonwalohale was destroyed, numerous Oneida defected from the rebellion and relocated to Fort Niagara to live under British protection.

1794 Treaty of Canandaigua

After the war, the Oneida were displaced by retaliatory and other raids. In 1794 they, along with other Haudenosaunee nations, signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States. They were granted 6 million acres (24,000 km²) of lands, primarily in New York; this was effectively the first Indian reservation in the United States. Subsequent treaties and actions by the State of New York drastically reduced their land to 32 acres (0.1 km²). In the 1830s many of the Oneida relocated into the province of Upper Canada and Wisconsin, because the United States was requiring Indian removals from eastern states.

Recent litigation

In 1970 and 1974 the Oneida Indian Nation of New York, Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, and the Oneida Nation of the Thames filed suit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York to reclaim land taken from them by New York without approval of the United States Congress. In 1998, the United States intervened in the lawsuits on behalf of the plaintiffs in the claim so the claim could proceed against New York State. The state had asserted immunity from suit under the Eleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution.[3] The Defendants moved for summary judgment based on the U. S. Supreme Court's decision in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation ()[4] and the 2nd Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals' decision in Cayuga Indian Nation v. New York ().[5] On May 21, 2007, Judge Kahn dismissed the Oneida's possessory land claims and allowed the non-possessory claims to proceed.[6]

More recent litigation has formalized the split and defined the separate interests of the Oneida tribe that stayed in New York and the Oneida tribe that left to live in Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Oneida tribe has brought suit to reacquire lands in their ancestral homelands as part of the settlement of the aforementioned litigation.[citation needed]

Oneida Bands and First Nations today

- Oneida Indian Nation in New York

- Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, in and around Green Bay, Wisconsin

- Oneida Nation of the Thames in Southwold, Ontario

- Oneida at Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario

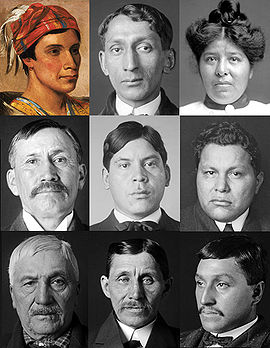

Notable Oneida

- Aaliyah, American Recording Artist was of African American and Oneida descent.

- Ohstahehte, the original Oneida Chief who accepted the Message of the Great Law of Peace.

- Graham Greene, actor.

- Lloyd L. House, PhD - Educator, First American Indian Elected to the Arizona State Legislature

- Cody McCormick, Canadian professional ice hockey player for Colorado Avalanche.

- Joanne Shenandoah, award-winning singer and performer.

- Tehaliwaskenhas Bob Kennedy (Turtle Island)

- Moses Schuyler, co-founder of the Oneida Nation of the Thames Settlement.

- Garrison Chrisjohn, X-Files actor.

- Alex Elijah I (Pine Tree Chief & Haudenosaunee Expert)

- Charlie Hill, comedian, entertainer.

- Mary Wheeler, land claims activist.

- Evan John I, oral historian, traditional agriculture and horticulture expert.

- Demus Elm, oral historian, Haudenosaunee expert.

- Polly Cooper, leader, friend of Washington.

- Venus Walker, oral historian, Haudenosaunee ceremonies expert.

- Loretta Metoxen, leader, Oneida historian.

- Dr. Eileen Antone, academic, adult education expert.

- Harley Elijah Sr., President of Ironworkers Union Local 700.

- Gino Odjick, Canadian former professional ice hockey player.

- Chief Skenandoah, Oneida leader during the American Revolution.

- Carl J. Artman, Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

- Dr. Roland Chrisjohn, Director of Native Studies at St. Thomas University (New Brunswick).

- Ernie Stevens Jr., Chairman of National Indian Gaming Association.

- Lillie Rosa Minoka Hill, 20th century Native American physician.

- Purcell Powless, tribal chairman of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin

Notes

- ^ Rudes, B. Tuscarora English Dictionary Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999

- ^ Glathaar, Martin.

- ^ http://www.madisoncounty.org/motf/fed128.html

- ^ City Of Sherrill V. Oneida Indian Nation Of N. Y

- ^ http://www.upstate-citizens.org/USDC-Oneida-SJ-MOL.pdf

- ^ http://www.upstate-citizens.org/USDC-Oneida-SJ-Decision.pdf

References

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. and James Kirby Martin. Forgotten Allies: the Oneida Indians and the American Revolution. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006.

- Levinson, David. "An Explanation for the Oneida-Colonist Alliance in the American Revolution." Ethnohistory 23, no. 3. (Summer, 1976), pp. 265–289. Online via JSTOR (account required)

External links

- Official website of the Oneida Indian Nation of New York

- Official website of the Sovereign Oneida Nation of Wisconsin

- Cofrin Library : Oneida Bibliography

- Oneida Indian Tribe of Wisconsin

- Official Website of the Oneida Nation of the Thames

- Oneida Nation of the Thames Radio Station Website

- Traditional Oneidas of New York

- Barbagallo, Tricia (June 1, 2005). "Black Beach: The Mucklands of Canastota, New York" (PDF). http://www.archives.nysed.gov/apt/magazine/MagSummer05FeatureArticle_000.pdf. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

Oneida people Groups

Oneida Indian Nation · Oneida Nation of Wisconsin · Oneida Nation of the ThamesHistory and Culture

Oneida language · Iroquois Confederacy · Treaty of CanandaiguaLitigation

Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State v. Oneida Cnty. (1974) · Oneida Cnty. v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State (1985) · City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. (2005)League of the Iroquois Nations Topics

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.